Horse meat

Horse meat (or horse beef) is the culinary name for meat cut from a horse. It is a major meat in only a few countries, notably in Central Asia, but it forms a significant part of the culinary traditions of many others, from Europe to South America to Asia. The top eight countries consume about 4.7 million horses a year. For the majority of humanity's early existence, wild horses were hunted as a source of protein.[1][2] It is slightly sweet, tender and low in fat.[3]

However, because of the role horses have played as companions and as workers, and concerns about the ethics of the horse slaughter process, it is a taboo food in some cultures. These historical associations, as well as ritual and religion, led to the development of the aversion to the consumption of horse meat. The horse is now given pet status by many in some parts of the Western world, particularly in the United States, United Kingdom and Ireland, which further solidifies the taboo on eating its meat.

History

In the late Paleolithic (Magdalenian Era), wild horses formed an important source of food. In many parts of Europe, the consumption of horse meat continued throughout the Middle Ages until modern times, despite a Papal ban of horse meat in 732.[4] Horse meat was also eaten as part of Germanic pagan religious ceremonies in northern Europe, particularly ceremonies associated with the worship of Odin.[citation needed]

Horses developed on the North American Continent and migrated to other parts of the world about 15,000 years ago. The largest fossil beds of horses is in Idaho at the Hagerman Fossil Beds, a National Monument. The horses were about the size of a modern day Arabian horse. The Europeans' horses that came over to the America's with the Spaniards and followed by the settlers became feral, and were hunted by the indigenous Pehuenche people of what is now Chile and Argentina.[5] At first they hunted horses as they did other game, but later they began to raise them for meat and transport. The meat was, and still is, preserved by being sun-dried in the high Andes into a product known as charqui.

France dates its taste for horse meat to the Revolution. With the fall of the aristocracy, its auxiliaries had to find new means of subsistence. Just as hairdressers and tailors set themselves up to serve commoners, the horses maintained by aristocracy as a sign of prestige ended up alleviating the hunger of lower classes.[6] It was during the Napoleonic campaigns when the surgeon-in-chief of Napoleon's Grand Army, Baron Dominique-Jean Larrey, advised the starving troops to eat the meat of horses. At the siege of Alexandria, the meat of young Arab horses relieved an epidemic of scurvy. At the battle of Eylau in 1807, Larrey served horse as soup and bœuf à la mode. At Aspern-Essling (1809), cut from the supply lines, the cavalry used the breastplates of fallen cuirassiers as cooking pans and gunpowder as seasoning, and thus founded a tradition that carried on until at least the Waterloo campaign.[7][8]

Horse meat gained widespread acceptance in French cuisine during the later years of the Second French Empire. The high cost of living in Paris prevented many working-class citizens from buying meat such as pork or beef, so in 1866 the French government legalized the eating of horse meat and the first butcher's shop specializing in horse meat opened in eastern Paris, providing quality meat at lower prices.[9] During the Siege of Paris (1870–1871), horse meat was eaten by anyone who could afford it, partly because of a shortage of fresh meat in the blockaded city, and also because horses were eating grain which was needed by the human populace. Many Parisians gained a taste for horse meat during the siege, and after the war ended, horse meat remained popular. Likewise, in other places and times of siege or starvation, horses are viewed as a food source of last resort.

Despite the general Anglophone taboo, horse and donkey meat was eaten in Britain, especially in Yorkshire, until the 1930s,[10] and in times of post-war food shortage surged in popularity in the United States[11] and was considered for use in hospitals.[12] A 2007 Time magazine article about horse meat brought in from Canada to the United States characterized the meat as sweet, rich, superlean, oddly soft meat, and closer to beef than venison.[13]

Taboo

Attitude of various cultures

Horse is commonly eaten in many countries in Europe and Asia.[14][15][16] It is not a generally available food in some English-speaking countries such as the United Kingdom, Ireland, the United States,[17] and English Canada. It is also taboo in Argentina, [18] Brazil, Israel, and among the Romani people and Jewish people the world over. Horse meat is not generally eaten in Spain (except in the north), although the country exports horses both "on the hoof and on the hook" (i.e., live animals and slaughtered meat) for the French and Italian market. Horse meat is consumed in some North American and Latin American countries, and is illegal in some countries. For example, the Food Standards Code of Australia and New Zealand definition of 'meat' does not include horse.[19] In Tonga, horse meat is eaten nationally, and Tongan emigrees living in the United States, New Zealand and Australia have retained the taste for it, claiming Christian missionaries originally introduced it to them.[20]

In Islamic laws, consuming horse meat is makruh or discouraged. However, it is not haram or forbidden. However, the consumption of horse meat has been common in Central Asia societies, past or present. This has been due to the propensity of steppes suitable for raising horses. In north Africa, horse meat has been occasionally consumed, but almost exclusively by the Christian Copts and the Hanafi Sunnis (a common form of Islam in Central Asia and Turkey), but has never been eaten in the Maghreb.[21]

Horse meat is forbidden by Jewish dietary laws because horses do not have cloven hooves and they are not ruminants.

In the eighth century, Popes Gregory III and Zachary instructed Saint Boniface, missionary to the Germans, to forbid the eating of horse meat to those he converted, due to its association with Germanic pagan ceremonies.[22][23] The people of Iceland allegedly expressed reluctance to embrace Christianity for some time, largely over the issue of giving up horse meat.[24] Horse meat is now currently consumed in Iceland and many horses are raised for this purpose. The culturally close people of Sweden still have an ambivalent attitude to horse meat, said to stem from this time.

Henry Mayhew describes the difference in the acceptability and use of the horse carcass in London and Paris in London Labour and the London Poor (1851).[25] Horse meat was rejected by the British, but continued to be eaten in other European countries such as France and Germany, where knackers often sold horse carcasses despite the Papal ban. Even the hunting of wild horses for meat continued in the area of Westphalia. Londoners also suspected that horse meat was finding its way into sausages, and that offal sold as that of oxen was in fact equine. About 1,000 horses were slaughtered a week.

In Russia, while there is no taboo on eating horse meat per se, horse meat is generally considered by ethnic Russians to be a low-quality meat with poor taste, and it is rarely found in stores. It is popular among nomadic peoples of Eastern Russia such as Tatars, Yakuts and Central Asia such as Kyrgyzs and Kazakhs.[26]

Reasons for the taboo

In 732 A.D., Pope Gregory III began a concerted effort to stop the ritual consumption of horse meat in pagan practice. In some countries, the effects of this prohibition by the Roman Catholic Church have lingered and horse meat prejudices have progressed from taboos, to avoidance, to abhorrence.[24] In other parts of the world, horse meat has the stigma of being something poor people eat and is seen as a cheap substitute for other meats, such as pork and beef.

According to the anthropologist Marvin Harris,[6] some cultures class horse meat as taboo because the horse converts grass into meat less efficiently than ruminants.

Totemistic taboo is also a possible reason for refusal to eat horse meat as an everyday food, but did not necessarily preclude ritual slaughter and consumption. Roman sources state that the goddess Epona was widely worshipped in Gaul and southern Britain. Epona, a triple aspect goddess, was the protectress of the horse and horse keepers, and horses were sacrificed to her;[27] she was paralleled by the Irish Macha and Welsh Rhiannon. In The White Goddess, Robert Graves argued that the taboo among Britons and their descendants was due to worship of Epona, and even earlier rites.[28] The Uffington White Horse is probable evidence of ancient horse worship. The ancient Indian Kshatriyas engaged in horse sacrifice (Ashwamedh Yaghya) as recorded in the Vedas and Ramayana; but within context of the ritual sacrificial is not being 'killed' but instead being smothered to death.[29] In 1913, the Finnic Mari people of the Volga region were observed to practice a horse sacrifice.[29]

In ancient Scandinavia, the horse was very important, as a living, working creature, as a sign of the owner's status, and symbolically within the old Norse religion. Horses were slaughtered as a sacrifice to the gods and the meat was eaten by the people taking part in the religious feasts.[30] When the Nordic countries were Christianized, eating horse meat was regarded as a sign of paganism and prohibited. A reluctance to eat horse meat is still common in these countries even today.[31]

Production

In most countries where horses are slaughtered for food, they are processed in a similar fashion to cattle, i.e., in large-scale factory slaughter houses (abattoirs) where they are stunned with a captive bolt gun and bled to death. In countries with a less industrialized food production system, horses and other animals are slaughtered individually outdoors as needed, in the village where they will be consumed, or near to it.[32]

In 2005, the eight principal horse-meat-producing countries produced over 700,000 tonnes of this product.

Major Horse meat Production Countries, 2005[33] Country Animals Production in metric tons China 1,700,000 204,000 Mexico 626,000 78,876 Kazakhstan 340,000 55,100 Mongolia 310,000 38,000 Argentina 255,000 55,600 Italy 213,000 48,000 Brazil 162,000 21,200 Kyrgyzstan 150,000 25,000 Worldwide

Totals4,727,829 720,168

In 2005, the 5 biggest horse meat-consuming countries were China (421,000 tonnes), Mexico, Russia, Italy, and Kazakhstan (54,000 tonnes).[34] In 2010, Mexico produced 140,000 tonnes, China - 126,000 tonnes, Kazakhstan - 114,000 tonnes.

As horses are relatively poor converters of grass and grain to meat compared to cattle,[6] they are not usually bred or raised specifically for their meat. Instead, horses are slaughtered when their monetary value as riding or work animals is low, but their owners can still make money selling them for horse meat, as for example in the routine export of the southern English ponies from the New Forest, Exmoor, and Dartmoor.[35][36] British law requires the use of "equine passports" even for semi-wild horses to enable traceability (also known as "provenance"), so most slaughtering is done in the UK before the meat is exported,[36] meaning that the animals travel "on the hook, not on the hoof" (as carcasses rather than live). Ex-racehorses, riding horses, and other horses sold at auction may also enter the food chain; sometimes these animals have been stolen or purchased under false pretenses.[37] Even famous horses may end up in the slaughterhouse; the 1986 Kentucky Derby winner and 1987 Eclipse Award for Horse of the Year winner, Ferdinand, is believed to have been slaughtered in Japan, probably for pet food.[38]

There is a misconception that horses are commonly slaughtered for pet food, however. In many countries, like the United States, horse meat was outlawed in pet food in the 1970s. American horse meat is considered a delicacy in Europe and Japan, and its cost is in line with veal,[39] so it would be prohibitively expensive in many countries for pet food.

The British newspaper The Daily Mail reports that every year, 100,000 live horses are transported into and around the European Union for human consumption, mainly to Italy but also to France and Belgium.[40]

Meat from horses that veterinarians have put down with a lethal injection is not suitable for human consumption, as the toxin remains in the meat; the carcasses of such animals are sometimes cremated (most other means of disposal are problematic, due to the toxin).[citation needed] Remains of euthanized animals can be rendered, which maintains the value of the skin, bones, fats, etc., for such purposes as fish food. This is commonly done for lab specimens (e.g., pigs) euthanized by injection. The amount of drug (e.g. a barbiturate) is insignificant after rendering.[citation needed]

Carcasses of horses treated with some drugs are considered edible in some jurisdictions. For example, according to Canadian regulation, hyaluron, used in treatment of articular disorders in horses, in HY-50 preparation should not be administered to animals to be slaughtered for horse meat.[41] In Europe, however, the same preparation is not considered to have any such effect, and edibility of the horse meat is not affected.[42]

Opposition to production

The killing of horses for human consumption is widely opposed in countries such as the U.S.,[43][44] UK[45] and Australia.[46] where horses are generally considered to be companion and sporting animals only.[47] Almost all equine medications and treatments are labeled as being not intended for human consumption.[citation needed] In the European Union, horses intended for slaughter cannot be treated with many medications commonly used for U.S. horses.[citation needed] For horses going to slaughter, there is no period of withdrawal between the time it leaves home and the time it is butchered. French actress and animal rights activist Brigitte Bardot has spent years crusading against the eating of horse meat. However, the opposition is far from unanimous; a 2007 readers' poll in the London magazine Time Out showed that 82% of respondents supported chef Gordon Ramsay's decision to serve horse meat in his restaurants.[48]

Nutritional value

| Food source | Calories | Protein | Fat | Iron | Sodium | Cholesterol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Game meat, horse, raw | 133 | 21 g | 5 g | 3.8 mg | 53 mg | 52 mg |

| Beef, strip steak, raw | 117 | 23 g | 3 g | 1.9 mg | 55 mg | 55 mg |

Preparation

Horse meat has a slightly sweet taste reminiscent of a combination of beef and venison. Meat from younger horses tends to be lighter in color while older horses produce richer color and flavor, as with most mammals. Horse meat can be used to replace beef, pork, mutton, venison and any other meat in virtually any recipe, although the cooking time is shorter than that of beef or pork. Horse meat is usually very lean and tender. Jurisdictions which allow for the slaughter of horses for food rarely have age restrictions, so many are quite old. However, unlike many other types of meat, horse meat becomes more tender as the animal advances in age.

Those preparing sandwiches or cold meals with horse meat usually use it smoked and salted. Horse meat forms an ingredient in several traditional recipes of salami.

Horse meat in various countries

In 2009, a British agriculture industry website reported the following horse meat production levels in various countries:

| Country | Tons per year |

|---|---|

| Mexico | 78,000 |

| Argentina | 57,000 |

| Kazakhstan | 55,000 |

| Mongolia | 38,000 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 25,000 |

| Australia | 24,000 |

| Brazil | 21,000 |

| Canada | 18,000 |

| Poland | 18,000 |

| Italy | 16,000* |

| Romania | 14,000 |

| Chile | 10,000 |

| France | 7,500 |

| Uruguay | 8,000 |

| Senegal | 9,500 |

| Colombia | 6,000 |

| Spain | 5,000* |

- * Including donkeys.

Asia-Pacific

Australia

Australians do not generally eat horse meat, although they have a horse slaughter industry that exports to Japan, Europe, and Russia.[53] Horse meat exports peaked at 9,327 tons 1986, declining to 3,000 tons in 2003. The two abattoirs in Australia licensed to export horse meat are Belgian-owned. They are at Peterborough in South Australia (Metro Velda Pty Ltd) and Caboolture abattoir in Queensland (Meramist Pty Ltd).[54] A British agriculture industry website reported that Australian horse meat production levels had risen to 24,000 tons by 2009.[52]

On 30 June 2010, the Western Australian Agriculture Minister Terry Redman granted final approval to Western Australia butcher Vince Garreffa to sell horse meat for human consumption. Nedlands restaurateur Pierre Ichallalene announced plans to do a taster on Bastille Day and to put horse meat dishes on the menu if there's a good reaction. Mr. Redman said that the Government would "consider extending approvals should the public appetite for horse demand it".[55]

Mr. Garreffa is the owner of Mondo Di Carne, a major wholesale meat supplier which supplies many cafes restaurants & hotels in Western Australia.[56][57] He commented that there is no domestic market for horse meat, but there is a successful export market, which he believes Western Australia should have a share of.[55]

For a short time an online petition had been created to stop the sale of horse meat for human consumption in Western Australia.[58] This decision caused outrage amongst some groups, limited reaction from many and ethusiasm from others. Several local newspaper forums indicated that the general public were not greatly biased either way, in fact many voiced their openness for alternate meats. [citation needed]

Horse meat consumption has continued as a niche market in Australia, with further potential for growth as gourmet interests develop.[citation needed]

China

Although it is generally acceptable to Chinese people, outside of specific areas such as Guilin in Guangxi or in Yunnan province, horse meat is not particularly popular due to its low availability and rumors that horse meat tastes bad or it is bad for health [citation needed]. In Compendium of Materia Medica, a pharmaceutical text published in 1596, Li Shizhen wrote "To relieve toxin caused by eating horse meat, one can drink carrot juice and eat almond." Today, in southern China, there are locally famous dishes such as Horse Meat Rice Noodles (马肉米粉; Pinyin: mǎ ròu mǐ fěn) in Guilin. In the northwest, Kazakh people eat horse meat (see below).

Kazakhstan

Indonesia

In Indonesia, one type of satay (chunks of grilled meat served with spicy sauce) known as Horse Satay (Javanese:sate jaran, Indonesian:sate kuda) is made from horse meat. This delicacy from Yogyakarta is served with sliced fresh shallot (small red onion), pepper, and sweet soy sauce.[61]

Japan

In Japanese cuisine, raw horse meat is called sakura (桜) or sakuraniku (桜肉) (sakura means cherry blossom, niku means meat) because of its pink color. It can be served raw as sashimi in thin slices dipped in soy sauce, often with ginger and onions added.[62] In this case, it is called basashi (馬刺し). Basashi is popular in some regions of Japan and is often served at izakaya bars. Fat, typically from the neck, is also found as basashi, though it is white, not pink. Horse meat is also sometimes found on menus for yakiniku (a type of barbecue), where it is called baniku (馬肉, literally "horse meat") or bagushi (馬串, "skewered horse"); thin slices of raw horse meat are sometimes served wrapped in a shiso leaf. Kumamoto, Nagano and Ōita are famous for basashi, and it is common in the Tohoku region as well. Some types of canned "corned meat" in Japan include horse as one of the ingredients.[63][64] There is also a dessert made from horse meat called basashi ice cream.[65] The company that makes it is known for its unusual ice cream flavors, many of which have limited popularity.

Mongolia

Mongolia, a nation famous for its nomadic pastures and equestrian skills, also includes horse meat on the menu. Mongolians also make a horse milk wine, called airag. Salted horse meat sausages called kazy are produced as a regional delicacy by the Kazakhs in Bayan-Ölgii aimag.[66] In modern times, Mongols prefer beef and mutton, though during the extremely cold Mongolian winter, many people prefer horse meat due to its low cholesterol. It is kept non-frozen and traditionally people think horse meat helps warm them up.[67]

Other Asian nations import processed horse meat from Mongolia.[68][69]

South Korea

In South Korea, horse meat is generally not eaten but raw horse meat, usually around the neck part, is consumed as a delicacy on Jeju island. It is usually seasoned with soy sauce and sesame oil.[70][71]

Tonga

In Tonga, horsemeat or "lo'i ho'osi" is much more than just a delicacy; the consumption of horsemeat is generally only reserved for special occasions. These special occasions may include the death of an important family member or community member or as a form of celebration during the birthday of an important family member or perhaps the visitation of someone important like the King of Tonga.

In Tonga, a horse is one of the most valuable animals a family can own because of its use as a beast of burden. Therefore the slaughter of one's horse for the purpose of consumption becomes a moment of immense homage to the person or event the horse was slain for. Despite a diaspora into Western countries like Australia, USA and New Zealand where consumption of horsemeat is generally tabooed, Tongans still practice the consumption of horse meat perhaps even more so because it is more readily available and more affordable.

Philippines

In the Philippines, horse meat is commonly sold in wet local markets. Horse meat is a famous delicacy. The method of preparation is very common which includes marinating the meat with kalamansi (or lemons), toyo (soy sauce), and patis (fish sauce). It is then fried and served, it is usually dipped into vinegar to give the meat a sour taste. It is known throughout the country as "Lukba", "Tapang Kabayo", or just simply "Kabayo".

Europe

In 2013, horse meat and traces of horse DNA were found in some food products where horse was not labelled as an ingredient, sparking the 2013 meat adulteration scandal across Europe.

Austria

Horse Leberkäse is available in special horse butcheries and occasionally at various stands, sold in a bread roll. Dumplings can also be prepared with horse meat, spinach or Tyrolean Graukäse (a sour milk cheese). They are occasionally eaten on their own, in a soup, or as a side-dish.

Belgium

In Belgium horse meat (paardenvlees in Dutch and viande chevaline in French) is popular in a number of preparations. Lean, smoked and sliced horse meat fillet (paardenrookvlees or paardengerookt; filet chevalin in French) is served as a cold cut with sandwiches or as part of a cold salad. Horse steaks can be found in most butchers and are used in a variety of preparations. The city of Vilvoorde has a few restaurants specialising in dishes prepared with horse meat. Horse-sausage is a well-known local specialty in Lokeren with European recognition.[72] Smoked or dried horse/pork meat sausage, similar to salami (called boulogne) is sold in a square shape to be distinguished from pork and/or beef sausages.[73][74]

France

Horse meat was famously eaten in large amounts during the 1870 Siege of Paris, when it was included in haute cuisine menus.

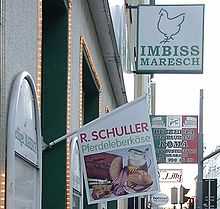

Germany

In Germany, horse meat is used e.g. for traditional Sauerbraten, a strongly marinated type of sweet-sour braised meat dish, at least according to the original Rhenish recipe. Other traditional horse meat dishes includes the Swabian Pferderostbraten (like roast-beef) and Bavarian Rosswurst, Ross-Leberkäse and Ross-Kochsalami (popular horse sausage varieties). However, as many people are hesitant to eat horse meat, Sauerbraten and other horse meat specialities are often substituted with beef instead. Horse meat is mainly sold by specialized Pferdemetzgereien (horse butcheries) and mail-order, of which there are about 70 nationwide, i.e. one for circa 1,170,000 inhabitants. Horse meat, a rather normal source of food in the past, is also occasionally used for steaks, roasts and goulash varieties throughout all parts of Germany, since it is known by gourmets to be by far healthier than beef and pork alike. Moreover, many cat and dog breeders and owners value horse meat as a resource for lean and healthy pet food.

At the beginning of February 2013, Germany was hit by a horse meat scandal that later widened to an EU-wide scandal. German authorities found mislabeled quantities of beef in frozen lasagna and other food products. Actually, the beef products were made out of horse meat which could be traced down to the Dutch company Draap and Romanian slaughterhouses. Although the detection of horse meat is not seen as food fraud, it is still a food safety issue. Horses used in sports could enter the food supply chain, meaning that the veterinary drug phenylbutazone could harm the consumers’ health. Therefore the EU authorities have decided to agree on a European solution and to speed up the publication process of the European Commission recommendation on labeling the origin of all processed meat.[75][76]

Hungary

In Hungary, horse meat is only used in salami and sausages, usually mixed with pork. These products are sold in most supermarkets and many butcher shops and are not particularly popular.

Iceland

In Iceland, it is both eaten minced and as steak, also used in stews and fondue, prized for its strong flavor. It has a particular role in the culture and history of the island. It has been said that the people of Iceland were reluctant to embrace Christianity for some time largely over the issue of giving up horse meat after Pope Gregory III banned horse meat consumption in 732 AD. Horse meat consumption was banned when the pagan Norse Icelanders eventually adopted Christianity in the year 1000,. The island eventually lifted the ban because of the starvation it caused.

Italy

Horse meat is especially popular in Lombardia, Veneto, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol, Parma, Apulia and the Islands of Sardinia and Sicily

Horse meat is used in a variety of recipes: as a stew called pastissada (typical of Verona), served as steaks, as carpaccio, or made into bresaola . Thin strips of horse meat called sfilacci are popular . Horse fat is used in recipes such as pezzetti di cavallo. Horse meat sausages and salamis are traditional in various places . In Sardinia sa petza 'e cuaddu or sa petha (d)e caddu (campidanese and logudorese for horse meat) is one of the most renowned meats and sometimes is sold in typical kiosks with bread - also in the town of Sassari there's a long tradition of eating horse steaks (carri di cabaddu in the local dialect). Chefs and consumers tend to prize its uniqueness by serving it as rare as possible. Donkey is also cooked, for example as a stew called stracotto d'asino and as meat for sausages e.g. mortadella d'asino . The cuisine of Parma features a horsemeat tartare called pesto di cavallo, as well as various cooked dishes.[77][78]

In Veneto the consumption of horse meat dates back to at least 1000-500 B.C. to the Adriatic Veneti, renowned for their horse-breeding skills. They were used to sacrifice horses to their goddess Reitia or to the mythical hero Diomedes.[79][80] Throughout the classical period, Veneto established itself as a centre for horse breeding in Italy; Venetian horses were provided for the cavalry and carriage of the Roman Legions with the white Venetic horses becoming famous among Greeks and Romans as one of the best breeds for circus racing.[81] As well as breeding horses for military and farming applications the Venetics also used them for consumption throughout the Roman period, a practice that established the consumption of Horse meat as a tradition in Venetian cuisine. In the modern age Horse meat is considered a luxury item and is widely available through supermarkets and butcheries, with some ultra-specialised butcheries offering only selected cuts of equine meat. Prices are usually higher than beef, pork and any other kind of meat, except game.

In the Province of Padua horse meat is a key element of the local cuisine; particularly in the area that extends south-east from the city, historically called Saccisica.[82] Specialties based on horse meat constitute the main courses and best attractions of several typical restaurants in the zone. They are also served among other regional delicacies at the food stands of many local festivals, related to civil and religious anniversaries. Most notable is the "Festa del Cavallo"; held annually in the small town of Legnaro and totally dedicated to horses, included their consumption for food.

Some traditional dishes are:

- Sfilacci di cavallo: tiny frayings of horse meat, dried and seasoned; to be consumed raw. Can be a light and quick snack. More and more popular as a topping on other dishes: ex. pasta, risotto, pizza, salads, etc.

Cavàeo in Umido (traditional horsemeat stew from Padua ) with grilled polenta.

Cavàeo in Umido (traditional horsemeat stew from Padua ) with grilled polenta. - Straéca: a thin soft horse steak, cut from the diaphragm, variously cooked and dressed on the grill, pan or hot-plate.

- Bistecca di puledro. colt steak, whose preparation is similar to straéca.

- Spezzatino di cavallo also said Cavàeo in umido. small chunks of horse meat, stewed with onion, parsley and/or other herbs and flavours, potatoes, broth, wine, etc. Usually consumed with polenta. Much appreciated is also a similar stew made of donkey meat, served in traditional trattorie, with many variations for different villages: Spessadin de musso, Musso in umido, Musso in tocio, Musso in pocio.

- Prosciutto di cavallo: horse ham, served in very thin slices.

- Salame di cavallo or Salsiccia di cavallo: various kinds of salami, variously produced or seasoned, sometimes made of pure equine meat, sometimes mixed with others (bovine or swine).

- Bigoli al sugo di cavallo: a typical format of fresh pasta, similar to thick rough spaghetti, dressed with sauce like bolognese, but made with minced horse meat.

In Southern Italy, horse meat is commonly eaten everywhere - especially in the region of Apulia, where it is considered a delicacy.[83][84] It is often a vital part of the ragù barese in Bari.[85]

According to British food writer Matthew Fort, "The taste for donkey and horse goes back to the days when these animals were part of everyday agricultural life. In the frugal, unsentimental manner of agricultural communities, all the animals were looked on as a source of protein. Waste was not an option."[86]

Malta

In Malta, stallion meat (Maltese: Laħam taż-żiemel) is usually fried or baked in a white wine sauce. A few horse meat shops still exist and it is still served in some restaurants.[87]

Netherlands

Norway

In Norway, horse meat is commonly used in cured meats, such as vossakorv and svartpølse, and less commonly as steak, hestebiff.

In pre-Christian Norway, horse was seen as an expensive animal. To eat a horse was to show one had great wealth, and to sacrifice a horse to the gods was seen as the greatest gift one could give. When Norwegians adopted Christianity, horse-eating became taboo as it was a religious act for pagans, and thus it was considered a sign of heresy.[91]

Poland

Live, old horses are often being exported to Italy to be slaughtered. This practice also garners controversy. Horses in Poland are treated mostly as companions and the majority of society is against the live export to Italy.[citation needed]

Serbia

Horse meat is generally available in Serbia, though mostly shunned in traditional cuisine. It is, however, often recommended by General Practitioners to persons who suffer from anemia. It is available to buy at three green markets in Belgrade, a market in Niš, and in several cities in ethnically mixed Vojvodina, where Hungarian and previously German traditions brought the usage.

Slovenia

Horse meat is generally available in Slovenia, and is highly popular in the traditional cuisine, especially in the central region of Carniola and in the Kras region. Colt steak (žrebičkov zrezek) is also highly popular, especially in Slovenia's capital Ljubljana, where it's part of the city's traditional regional cuisine. In Ljubljana, there are also many restaurants that sell burgers and meat that contain large amounts of horse meat, including a fast food chain called Hot Horse.[92][93]

Sweden

Smoked/cured horse meat is widely available as a cold cut under the name hamburgerkött (hamburger meat). It tends to be very thinly sliced and fairly salty, slightly reminiscent of deli-style ham. Gustafskorv, a smoked sausage made from horse meat, is also quite popular, especially in the province of Dalarna, where it's made. It is similar to salami or metworst and is used as an alternative to them on sandwiches. It is also possible to order horse beef from some well-stocked grocery stores.

Switzerland

The ordinance on foodstuffs of animal origin in Switzerland explicitly list equines as an animal species allowed for the production of food.[94] Horse steak is quite common, especially in the French-speaking west, but also more and more in the German-speaking part. A speciality known as mostbröckli is made with beef or horse meat. Horse meat is also used for a great range of sausages in the German-speaking north of Switzerland. Like in northern Italy, in the Italian-speaking South, local "salametti" (sausages) are sometimes made with horse meat. Horse meat may also be used in Fondue Bourguignonne.

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, the slaughter, preparation and consumption of horses for food is not against the law, although it has been rare since the 1930s and it is not generally available. It was eaten when other meats were scarce, such as during times of war[95][96] (as was whale meat, which was never popular in Britain). The sale of meat labelled as horse meat in supermarkets and butchers is minimal, and most of the properly described horse meat consumed in the UK is imported from Europe, predominantly the South of France, where it is more widely available.[97]

Horse meat may be eaten without the knowledge of the consumer, due to accidental or fraudulent introduction of horse meat into human food. A 2003 Food Standards Agency (FSA) investigation revealed that salami and similar products such as chorizo and pastrami sometimes contain horse meat without it being listed,[98] although listing is legally required.[99]

Ukraine

In Ukraine, especially in Crimea and other southern steppe regions, horse meat is consumed in the form of sausages called Mahan and Sudzhuk. These particular sausages are traditional food of the Crimean Tatar population.

North America

Canada

There is a thriving horse meat business in Quebec; the meat is available in most supermarket chains. Horse meat is also for sale at the other end of the country, in Granville Island Market in downtown Vancouver where, according to a Time magazine reviewer who smuggled it into the United States, it turned out to be a "sweet, rich, superlean, oddly soft meat, closer to beef than venison".[13] Horse meat is also available in high end Toronto butchers and supermarkets. Aside from the heritage of French cuisine at one end of the country and the adventurous foodies of Vancouver at the other, however, the majority of Canada shares the horse meat taboo with the rest of the Anglosphere. This mentality is especially evident in Alberta, where strong horse racing and breeding industries and cultures have existed since the province's founding, although large numbers of horses are slaughtered for meat in Fort MacLeod, and certain butchers in Calgary do sell it.

CBC News reported on March 10, 2013 that horse meat was also popular among some segments of Toronto's population. The article also reported that countries where horse meat is part of the diet include France, Russia, Kazakhstan, China and Italy.[100]

United States

Horse meat is rarely eaten in the United States. Horse meat holds a taboo in American culture which is very similar to the one found in the United Kingdom (previously described), except that it is rarely even imported.

Restriction of human consumption of horse meat in the U.S. has generally involved legislation at the state and local levels. In 1915, for example, the New York City Board of Health amended the sanitary code, making it legal to sell horse meat.[101] During World War II, due to the low supply and high price of beef, New Jersey legalized its sale, but at war's end, the state again prohibited the sale of horse meat.

In 1951, Time magazine reported from Portland, OR: "Horsemeat, hitherto eaten as a stunt or only as a last resort, was becoming an important item on Portland tables. Now there were three times as many horse butchers, selling three times as much meat." Noting that "people who used to pretend it was for the dog now came right out and said it was going on the table," and providing tips for cooking pot roast of horse and equine fillets. A similar situation unfolded in 1973, when inflation raised the cost of traditional meats. Time reported that "Carlson's, a butcher shop in Westbrook, CT that recently converted to horse meat exclusively, now sells about 6,000 pounds of the stuff a day." The shop produced a 28-page guide called "Carlson's Horsemeat Cook Book" with recipes for chili con carne, German meatballs, beery horsemeat, and more.[102]

Harvard University's Faculty Club had horse meat on the menu for over one hundred years, until 1985.[103][104]

California Proposition 6 (1998) was passed by state voters, outlawing the possession, transfer, reception or holding any horse, pony, burro or mule by a person who is aware that it will be used for human consumption, and making the slaughter of horses or the sale of horsemeat for human consumption a misdemeanor offense.[105]

Until 2007, a few horse meat slaughterhouses still existed in the United States, selling meat to zoos to feed their carnivores, and exporting it for human consumption, but the last one, Cavel International in Dekalb, Illinois, was closed by court order in 2007.[106][107] The closure reportedly caused a surplus of horses in Illinois.[108]

On November 18, 2011, the ban on the slaughter of horses for meat was lifted as part of the Consolidated and Further Continuing Appropriations Act for Fiscal Year 2012.[109]

Mexico

As of 2005, Mexico was the second largest producer of horse meat in the world.[33] It is used there both for human consumption and animal food.[citation needed]

South America

Chile

In Chile, it is used in charqui. Also in Chile, horse meat became the main source of nutrition for the nomadic indigenous tribes, which promptly switched from a guanaco-based economy to a horse-based one after the horses brought by the Spaniards bred naturally and became feral. This applied specially to the Pampa and Mapuche nations, who became fierce horseman warriors. Similar to the Tatars, they ate raw horse meat and milked their animals.

Colombia

In Colombia, eating horse meat is considered taboo.

Argentina

Argentina is a producer and exporter of horse meat, but it is not used in local consumption and is considered taboo.[18]

Venezuela

In Venezuela, eating horse meat is considered taboo.

See also

- Blood of the Beasts (Le Sang des bêtes), a 1949 documentary film

- List of meat animals

- Repugnant market

People

- Carl C. Rasmussen, Los Angeles City Council member in the 1940s, revealed during a City Council discussion in the midst of World War II meat rationing over whether to adopt an ordinance requiring that charcoal be added to all horse meat offered for sale in the city, that he had served "dinner filets" made of horse meat to his guests and "they said they were delicious." He added: "I gave one of the steaks to the Mayor [Bowron], but he said his wife was out of town and he had to feed it to the dog."[110]

References

- ↑ Melinda A. Zeder (2006). Documenting Domestication. University of California Pres. pp. 257, 258, 265. ISBN 0-520-24638-1

- ↑ David W. Anthony (2008). The Horse, the Wheel and Language. Princeton University Press. pp. 199, 220. ISBN 0-691-05887-3

- ↑ ""Characteristics of the meat", Viande Richelieu, Inc. Covers Nutrients, Age, The sex of the animal, Race, Color, Tenderness, Taste, and Meat cuts". Vianderichelieu.com. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ↑ Richard Pillsbury (1998). No foreign food: the American diet in time and place. Westview Press. pp. 14. ISBN 978-0-8133-2739-6.

- ↑ Fernando Terrejón G. (2001). Exotic Livestock production and the Transition. "Geohistorical Variables in the Evolution of the Pehuenche Economic System During the Colonial Period". Universum Magazine (in Spanish) (University of Talca) 16: 226 (Spanish title: El Ganado Exótico Y la Transición Prodictiva , Variables Geohistóricas en la Evolución del Sistema Económicl Pehuenche Durante el periodo Colonio).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Harris, Marvin (1998). Good to Eat: Riddles of Food and Culture. Waveland Pr Inc. ISBN 1-57766-015-3

- ↑ Larrey is quoted in French by Dr Béraud, Études Hygiéniques de la chair de cheval comme aliment, Musée des Familles (1841-42).

- ↑ Larrey mentions in his memoirs how he fed the wounded after the (1809) with bouillon of horse meat seasoned with gunpowder. Parker, Harold T. (1983 reprint) Three Napoleonic Battles. (2nd Ed). Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-0547-X. Page 83 (in Google Books). Quoting Dominique-Jean Larrey, Mémoires de chirurgie militaire et campagnes, III 281, Paris, Smith.

- ↑ Kari Weil, "They Eat Horses, Don't They? Hippophagy and Frenchness", Gastronomica Spring 2007, Vol. 7, No. 2, Pages 44-51 Posted online on May 22, 2007. doi:10.1525/gfc.2007.7.2.44

- ↑ Eating Up Italy: Voyages on a Vespa by Matthew Fort. 2005, p253. ISBN 0-00-721481-2

- ↑ Charles Grutzner, Horse Meat Consumption By New Yorkers Is Rising; Newark Dealer Reports 60% of Customers Are From City--Weinstein Will Not Prohibit Sale of the Flesh Here 25 Sept 1946

- ↑ James E. Powers, NEAR-BY HOSPITALS DOWN TO MINIMUM OF MEAT SUPPLIES, The New York Times, 29 September 1946

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Stein, Joel (2007-02-08). "Horse — It's What's for Dinner". Time.com. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ↑ Cecilia Rodriguez (2012-04-18). "No American Horse Steak for You, Europeans". Forbes. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ↑ http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/09/sports/drugs-injected-at-the-racetrack-put-europe-off-us-horse-meat.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0

- ↑ "2008 - It is Time to Tell the Truth ...about Horse Slaughter". flyingfilly.com. Archived from the original on 2008-04-18. Retrieved 2008-05-20 (See the list headed "Horsemeat—By Any Other Name")

- ↑ Bordonaro, Lori. "Horse Meat on Menu Raises Eyebrows". NBC New York. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "Carne de caballo, el negocio tabú que florece en la Argentina". La Nación (in Spanish). Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ↑ "Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code 2.2.1 Meat and meat products". Comlaw.gov.au. 2012-05-20. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ↑ Simoons, F.J., 1994, Eat not this Flesh, Food Avoidances from Pre-history to Present, University of Wisconsin Press.

- ↑ Françoise Aubaile-Sallenave, "Meat among Mediterranean Muslims: Beliefs and Praxis", Estudios del Hombre 19:129 (2004)

- ↑ William Ian Miller, "Of Outlaws, Christians, Horsemeat, and Writing: Uniform Laws and Saga Iceland", Michigan Law Review, Vol. 89, No. 8 (Aug., 1991), pp. 2081-2095 (subscription required)

- ↑ Calvin W. Schwabe, Unmentionable Cuisine, University Press of Virginia, ISBN 0-8139-1162-1

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 "U.S.D.A. Promotes Horse & Goat Meat". International Generic Horse Association. Retrieved 2007-08-09. (quoting a 1997 USDA report said to be no longer available online)

- ↑ vol 2 p 7-9

- ↑ "Конина: вред и польза" (in Russian).

- ↑ Powell, T. G. E., 1958, The Celts, Thames and Hudson, London

- ↑ Graves, Robert, The White Goddess, Faber and Faber, London, 1961, p 384

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Campbell, Joseph, Oriental Mythology: The Masks of God, Arkana, 1962, pp190-197 ISBN 0-14-019442-8

- ↑ Phillip Pulsiano; Kirsten Wolf (1993). Medieval Scandinavia: an encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. p. 523. ISBN 978-0-8240-4787-0.

- ↑ Anders Andrén; Kristina Jennbert; Catharina Raudvere (2006). Old Norse Religion in Long Term Perspectives: Origins, Changes and Interactions, an International Conference in Lund, Sweden, June 3–7, 2004. Nordic Academic Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-91-89116-81-8.

- ↑ C.J. Chivers, A Sure Thing for Kazakhs: Horses Will Provide The New York Times

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 "THE UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCES OF A BAN ON THE HUMANE SLAUGHTER (PROCESSING) OF HORSES IN THE UNITED STATES" (PDF). The Animal Welfare Council, Inc., citing FAO-UN Horticultural Database. May 15, 2006. p. 10. Archived from the original on 2011-07-07. Retrieved 2008-11-06

- ↑ "The Alberta Horse Welfare Report, 2008" (PDF). Archived from the original on 2012-03-19. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ↑ "BBC Inside Out - New Forest Ponies". Bbc.co.uk. 2003-02-24. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 "NFU Countryside Online: Passports for Ponies". BBC Inside Out. Archived from the original on 2006-10-07. Retrieved 2006-10-07.

- ↑ "Slaughter of Lady". Netposse.com. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ↑ "Death of a Derby Winner". Horsesdaily.com. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ↑ "Horsemeat in France - (June 2006), Librairie des Haras nationaux" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ↑ Tom Rawstone (19 May 2007). "The English horses being sent to France to be eaten". Daily Mail. Retrieved 2007-10-04.

- ↑ HY-50 for veterinary use (archived from the original on 2011-10-06).

- ↑ "Genitrix HY-50 Vet brochure". Genitrix.co.uk. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ↑ Poll Finds Most Americans Against Horse Slaughter

- ↑ Time: Horse—It's What’s for Dinner

- ↑ Week in pictures - Who wants to eat horsemeat?

- ↑ Victorian Advocates for Animals & Coalition for the Protection of Racehorses protests

- ↑ "Americans squeamish over horse meat". St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ↑ Time Out 30 May–5 June 2007

- ↑ "Nutrition Facts and Analysis for Game meat, horse, raw". Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- ↑ "Nutrition Facts and Analysis for Beef, grass-fed, strip steaks, lean only, raw". Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- ↑ Pino, Darya (7 January 2011). "How Nutritious Is Horse? The Other Red Meat". Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 "Argentina-Horse Meat world production figures, Farming UK, January 17, 2009. Retrieved March 4, 2011". Farminguk.com. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ↑ "Exporting red meat to Russia: Understanding the context". Australian National Internships Program. 7 October 2010. Retrieved 2013-02-27.

- ↑ "Horse slaughter and horsemeat: the facts". Optimail.com.au. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 "Butcher gives horse meat a run". Au.news.yahoo.com. 2010-07-01. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ↑ Welcome to the Mondo's Family

- ↑ Mondo Wholesale Meat Supplies

- ↑ "Stop the sale of horse meat for human consumption in Western Australia". Change.org. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ↑ ""Food in Kazakhstan". ''Food in Every Country''". Foodbycountry.com. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ↑ Horse meat dishes in Kazakhstan. Retrieved 13 January 2009. (archived from the original on 2008-06-10)

- ↑ "Lesehan Jaran - Jogja". April 2, 2007.

- ↑ Metropolis, "Straight From the Horse's Mouth", #903, 15 July 2011, pp. 12-13.

- ↑ Brief Overview of the Draft Revision of Quality Labeling Standard for Canned and Bottled Livestock Products, Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (from PuntoFocal Argentina).

- ↑ "NOTIFICATION, World Trade Organization, 16 January 2006". Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ↑ Clay Thompson (14 December 2006). When it comes to eating horse, most say nay. The Arizona republic. Retrieved 2007-11-15

- ↑ Michael Kohn, (2008). Mongolia. Lonely Planet. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-74104-578-9.

- ↑ What to Eat in Mongolia, khaliuntravel.com

- ↑ Tasting Mongolian horse meat at Seventeen Saloon, hochiminhcity.gov.vn

- ↑ Meat Production in Mongolia, canada-mongolia-connection.com

- ↑ "Full horse course an unforgettable experience". Jejuweekly.com. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ↑ Exploring Jeju’s Savory Delicacies, koreana.or.kr

- ↑ "I could eat a horse". Flanders Today. 2009-11-18. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ↑ Janssens, M.; Myter, N.; De Vuyst, L.; Leroy, F. (2012). "Species diversity and metabolic impact of the microbiota are low in spontaneously acidified Belgian sausages with an added starter culture of Staphylococcus carnosus". Food Microbiology 29 (2): 167–177. doi:10.1016/j.fm.2011.07.005. PMID 22202870.

- ↑ Janssens, M.; Myter, N.; De Vuyst, L.; Leroy, F. (2012). "Species diversity and metabolic impact of the microbiota are low in spontaneously acidified Belgian sausages with an added starter culture of Staphylococcus carnosus". Food Microbiology 29 (2): 167–177. doi:10.1016/j.fm.2011.07.005. PMID 22202870.

- ↑ German Press Review Spiegel.de, Retrieved 04/17/2013

- ↑ EU-wide Meat Testing for Horsemeat SGS Food Safety Bulletin, Retrieved 04/16/2013

- ↑ Heigh Ho, Silver Eating Weird: Exploring Strange and Unusual Food in Seattle

- ↑ Pesto di Cavallo deledda's kitchen (in Italian)

- ↑ The Latin Language by Leonard Robert Palmer. University of Oklahoma Press 1988. p 41

- ↑ Runic Amulets and Magic Objects by Mindy MacLeod and Bernard Mees. The Boydell Press 2006. p 108

- ↑ An early History of Horsemanship by Augusto Azzaroli. Brill 1985. p 135-138

- ↑ Saccisica and Conselvano Official site of the Padua Province. Tourist Section.

- ↑ Fabio Parasecoli (2004). Food culture in Italy. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-313-32726-1.

- ↑ Paula Hardy; Abigail Hole; Olivia Pozzan (2008). Puglia & Basilicata. Lonely Planet. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-74179-089-4.

- ↑ "Brasciole or meat rolls filled with pecorino and fat : Authentic Italian recipe of Apulia". theitaliantaste.com.

- ↑ Eating Up Italy: Voyages on a Vespa by Matthew Fort. 2005, p253-254. ISBN 0-00-721481-2

- ↑ Carolyn Bain (2004). Malta & Gozo. Lonely Planet. p. 56. ISBN 174059178X. Retrieved 2007-09-14. "Did you know? Many of the village restaurants specialising in rabbit also feature horse meat on their menu."

- ↑ Brabants Dagblad "Deurnese vinding de frikandel", 19 February 2009

- ↑ "Lokerse paardenworsten". Streekproduct.be. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ↑ "Erkende Lokerse paardenworst wil Europees". Nieuwsblad.be. 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ↑ Jochens, Jenny (1998). Women in Old Norse Society. Cornell University Press. pp. 87–88. ISBN 978-0-8014-8520-6

- ↑ "Hot Horse". ljubljana-life.com. Retrieved 2007-12-03.

- ↑ Dan Ryan (14 December 2006). "Taste Ljubljana—Capital Ideas". Archived from the original on 2008-02-10. Retrieved 2007-12-03

- ↑ FDHA Ordinance of 23 November 2005 on food of animal origin, Art.2.

- ↑ "BBC Radio 4 - Factual - Food Programme - 11 April 2004". Bbc.co.uk. 2004-04-11. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ↑ "WW2 People's War - Horsemeat, A Wedding Treat". BBC. 2005-11-25. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ↑ "We Should Eat Horse Meat". Daily Telegraph.

- ↑ "Horse meat found in salami". BBC News. June 4, 2003.

- ↑ "[ARCHIVED CONTENT] Food Standards Agency - Labelling rules". Tna.europarchive.org. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ↑ "Toronto restaurateurs say horse meat a prime dining choice". CBC News. March 10, 2013.

- ↑ ALLOW HORSE MEAT FOR FOOD IN CITY The New York Times, 22 December 1915

- ↑ Christa Weil (March 5, 2007). We Eat Horses, Don't We?. The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-09-05

- ↑ "The Pros and Cons of Eating Horses". Online.wsj.com. 2005-10-01. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ↑ About the Club : History, The Harvard Faculty Club

- ↑ "Criminal Law. Prohibition on Slaughter of Horses and Sale of Horsemeat for Human Consumption. Initiative Statute.". California Secretary of State. 1998. Retrieved September 12, 2012.

- ↑ BELTEX CORPORATION; DALLAS CROWN, INC., v. TIM CURRY, District Attorney Tarrant County, 05-11499 (19 January 2007).

- ↑ Tara Burghart (29 June 2007). "Last US Horse Slaughterhouse to Close". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 2007-07-16.

- ↑ WIFR (Illinois), "Cavel International Shutdown Causes Abundance of Horses", March 26, 2008

- ↑ "Horse: Coming soon to a meat case near you?". CNN. Retrieved 2011-12-01.

- ↑ "Councilman Discloses He Served Horse-Meat Dinner," Los Angeles Times, May 3, 1944, page 1

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Horse meat. |

- "U.S.D.A. Promotes Horse & Goat Meat". International Generic Horse Association. Retrieved 2007-08-09. (quoting a 1997 USDA report said to be no longer available online)

- La Viande Chevaline, a web site made by the French Horse Meat Industry structure, called Interbev Equins (French)

- On eating horse meat sashimi AsiaObscura.com

- Yes, Russians eat horse meat Windows to Russia

| |||||||||||||||||||||||