Horace Capron

| Horace Capron | |

|---|---|

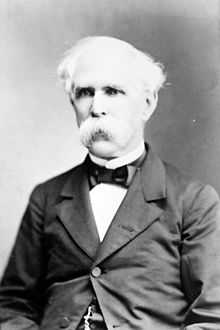

Horace Capron (approx. 1861–1865) | |

| Born |

August 31, 1804 Attleboro, Massachusetts |

| Died |

February 22, 1885 (aged 80) Washington, D.C. |

| Buried at | Oak Hill Cemetery, Georgetown, Washington, D.C. |

| Allegiance |

Union |

| Service/branch |

Union Army |

| Years of service | 1862–1865 |

| Rank |

|

| Commands held |

|

| Battles/wars | Battle of Chancellorsville |

| Awards | Order of the Rising Sun |

| Other work | U.S. Commissioner of Agriculture; advisor to Japan |

Horace Capron (August 31, 1804 – February 22, 1885) was an American businessman and agriculturalist, a founder of Laurel, Maryland, a Union officer in the American Civil War, the United States Commissioner of Agriculture under U.S. Presidents Andrew Johnson and Ulysses S. Grant, and an advisor to Japan's Hokkaidō Development Commission.[1] His collection of Japanese art and artifacts was sold to the Smithsonian Institution after his death.[2]

Early life

Horace Capron was born in Attleboro, Massachusetts, the son of Seth Capron and his wife Eunice Mann Capron.[1] His sister was Louisa Thiers (1814–1926), who in 1925 became the first verified person to reach age 111. His father, a doctor of medicine, opened woollen mills in New York State including Whitesboro, and from this experience Horace went on to supervise several cotton mills including Savage Mill in Savage, Maryland. He was also an officer in the Maryland Militia in the 1830s. In November 1834, Capron and others gathered suspects and potential witnesses of two recent Laurel railroad murders and brought them to Merrill's tavern. Some 300 railroad workers were questioned at the Baltimore county jail.[3]

In 1834, Horace married Louisa Victoria Snowden, whose late father Nicholas had owned Montpelier Mansion. This marriage brought lands and property. They had six children before Louisa died in 1849:[4] Nicholas Snowden Capron, who died in infancy; Adeline Capron, who died at age 17 in Illinois; Horace Capron, Jr., who received the Medal of Honor after being killed in the Civil War;[5] Albert Snowden Capron; Elizabeth Capron Mayo; and Osmond Tiffany Capron.

Capron was involved in the mechanization of cotton mills beginning in 1835, having worked in mills from boyhood in Massachusetts and New York. In 1836 he was a major force in forming the Patuxent Manufacturing Company, which operated the Laurel Mill, a cotton mill on the Patuxent River, and with this effort he and associates started what became the town of Laurel Factory, later Laurel, Maryland. In 1851 the mill failed, and Capron declared bankruptcy. Soon after, he obtained an appointment from the President to assist in removal and resettlement of Native Americans from Texas following the Mexican-American War. He spent several months in Texas, and then moved to a farm near Hebron, Illinois where his mother Eunice and sister Louisa Thiers had settled and were taking care of his children. Here, he built an imposing mansion. In Illinois, he was remarried to Margaret Baker and took up farming in earnest, experimenting with farming improvements, writing articles, participating in events and receiving awards for his work.

Military service

In the American Civil War, Capron was called upon to establish and later lead the 14th Illinois Cavalry regiment. He was the oldest cavalry officer in the Union Army. Seeing action in a number of skirmishes and battles, ranging from Kentucky to Georgia, and losing his eldest son in battle, he left the army with an injury in 1864 and was later given the rank of Brevet Brigadier General dated to February 13, 1865.[6]

His earlier experiences led to an appointment in 1867 as a Commissioner in the Department of Agriculture for the United States Government.

Japan

Capron was asked by Kiyotaka Kuroda, a vice-chairman of the Hokkaidō Development Commission (開拓使 Kaitakushi) visiting the United States, to be a special advisor to the commission in Hokkaidō, Japan. Capron agreed and travelled to Hokkaidō 1870–71 as a foreign advisor. The Japanese government paid him $10,000 plus expenses to undertake this mission, which was a tremendous sum for the time. Capron needed the money, as his son Osmond had been blinded in a hotel fire, and now depended on Capron for support.

Capron spent four years in Hokkaidō, suggesting numerous ways that the frontier island could be developed. He introduced large-scale farming with American methods and farming implements, imported seeds for western fruits, vegetables and crops, and introduced livestock, including his favorite Devon and Durham cattle. He established experimental farms, had the land surveyed for mineral deposits and farming opportunities, and recommended water, mill, and road improvements. His recommendation that wheat and rye be planted in Hokkaidō due to similarities in climate with parts of the United States also led to the establishment of Sapporo Beer, one of Japan's first breweries. He contributed to the urban planning for Sapporo city with an American-style grid plan with streets at right-angles to form city blocks.

Capron's tenure in Japan was not without controversy. Articles appeared in both Japan and the United States by former associates attacking his work and his personal competency. He was often frustrated with delays in the implementation of his suggestions, or on occasion the rejection of his suggestions by more conservative members of the government. However, Kuroda Kiyotaka, future Prime Minister of Japan, was a close and trusted friend. Capron admired the Ainu of Hokkaidō, whom he compared favorably to his experiences with Native Americans. From his journals, it appears that he also admired the Japanese, although he regarded them as semi-barbaric, and firmly believed that rapid adoption of Western culture would be in Japan's best interest.

During his stay in Japan, Capron was honored with three audiences with Emperor Meiji, who took a close personal interest in his work in the development of Hokkaidō. In 1884, nine years after he departed Japan, Horace Capron was awarded the Order of the Rising Sun (2nd class) for his services in transforming Hokkaidō.[2]

Final period

After his time in Japan, Capron continued his contacts with the country, including acting as a purchasing agent for livestock and military equipment, and selling his house on N Street in Washington, D.C. to be the site of Japan's first Embassy. He was also engaged in writing his memoirs during this period.

Capron attended the dedication of the Washington Monument on February 21, 1885. The extreme cold of the day, recorded at 12° Fahrenheit (−11° Celsius), was too much for the 80-year-old Horace Capron; he suffered a stroke, and died the following day. He is buried in Oak Hill Cemetery in Georgetown, Washington, D.C..

During his period in Japan, Capron amassed a large collection of Japanese art and antiques. After his death, his widow Margaret sold the collection to the Smithsonian, where it became one of the foundations of the Smithsonian's Asian collection.

Notes

- Horace Capron, Memoirs of Horace Capron 2 vols., typed copy, National Agricultural Library, U.S. Department of Agriculture

- Horace Capron. Reports and Official Letters by Horace Capron, Commissioner and Advisor and His Foreign Assistants (Tokyo: 1875)

- Merrit Starr. General Horace Capron, 1804–1884 Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 18 (July 1925): 259–349.

- Fujita Fumiko. American Pioneers and the Japanese Frontier: American Experts in Nineteenth-Century Japan Greenwood Press (1994)

- Harold S. Russell, "Time to Become Barbarian: The Extraordinary Life of General Horace Capron", Univ. Press of America (2007).

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 The Laurel Historical Society. "Fifty-First Congress, 1889–1891". Horace Capron at 200: A Laurel Founder's Life. pp. 1279–1291. Archived from the original on 2006-11-12. Retrieved 2007-04-25.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Smithsonian Institution (1901). Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections.

- ↑ Hezekiah Niles, William Ogden Niles, George Beatty, Jeremiah Hughes (1835). Niles' Weekly Register 47. H. Niles. p. 272. Retrieved November 9, 2013. "They ... recommended the apprehension of all persons employed on the line of the rail road, near where the murders ... had been committed. ... On the morning of the 26th, captain Bouldin ... marched to the Savage factory, and thence to that part of the railroad which was near the place of the recent murders, and ... apprehended many suspicious persons, whom, with several prisoners taken by major Capron, they brought to Merrill's tavern.... I submitted the whole of our prisoners, upwards of 300 ... to Baltimore county jail...."

- ↑ National Society of the Colonial Dames of America. Historic graves of Maryland and the District of Columbia. p. 89.

- ↑ Eugene L. Meyer (June 22, 2000). "Courage Remembered; Medal of Honor Winners Recognized". The Washington Post.

- ↑ The Photographic History of the Civil War: Three Volumes in One. New York: Random House Value Publishing, Inc. 1983. p. 308. 0-517-20155-0.

External links

- Detailed external biography

- Memoirs of Horace Capron; Autobiography

- Memoirs of Horace Capron; Expedition to Japan, 1871–1875

|