Hopcroft–Karp algorithm

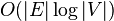

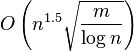

In computer science, the Hopcroft–Karp algorithm is an algorithm that takes as input a bipartite graph and produces as output a maximum cardinality matching – a set of as many edges as possible with the property that no two edges share an endpoint. It runs in  time in the worst case, where

time in the worst case, where  is set of edges in the graph, and

is set of edges in the graph, and  is set of vertices of the graph. In the case of dense graphs the time bound becomes

is set of vertices of the graph. In the case of dense graphs the time bound becomes  , and for random graphs it runs in near-linear time.

, and for random graphs it runs in near-linear time.

The algorithm was found by John Hopcroft and Richard Karp (1973). As in previous methods for matching such as the Hungarian algorithm and the work of Edmonds (1965), the Hopcroft–Karp algorithm repeatedly increases the size of a partial matching by finding augmenting paths. However, instead of finding just a single augmenting path per iteration, the algorithm finds a maximal set of shortest augmenting paths. As a result only  iterations are needed. The same principle has also been used to develop more complicated algorithms for non-bipartite matching with the same asymptotic running time as the Hopcroft–Karp algorithm.

iterations are needed. The same principle has also been used to develop more complicated algorithms for non-bipartite matching with the same asymptotic running time as the Hopcroft–Karp algorithm.

Augmenting paths

A vertex that is not the endpoint of an edge in some partial matching  is called a free vertex. The basic concept that the algorithm relies on is that of an augmenting path, a path that starts at a free vertex, ends at a free vertex, and alternates between unmatched and matched edges within the path. If

is called a free vertex. The basic concept that the algorithm relies on is that of an augmenting path, a path that starts at a free vertex, ends at a free vertex, and alternates between unmatched and matched edges within the path. If  is a matching, and

is a matching, and  is an augmenting path relative to

is an augmenting path relative to  , then the symmetric difference of the two sets of edges,

, then the symmetric difference of the two sets of edges,  , would form a matching with size

, would form a matching with size  . Thus, by finding augmenting paths, an algorithm may increase the size of the matching.

. Thus, by finding augmenting paths, an algorithm may increase the size of the matching.

Conversely, suppose that a matching  is not optimal, and let

is not optimal, and let  be the symmetric difference

be the symmetric difference  where

where  is an optimal matching. Then

is an optimal matching. Then  must form a collection of disjoint augmenting paths and cycles or paths in which matched and unmatched edges are of equal number; the difference in size between

must form a collection of disjoint augmenting paths and cycles or paths in which matched and unmatched edges are of equal number; the difference in size between  and

and  is the number of augmenting paths in

is the number of augmenting paths in  . Thus, if no augmenting path can be found, an algorithm may safely terminate, since in this case

. Thus, if no augmenting path can be found, an algorithm may safely terminate, since in this case  must be optimal.

must be optimal.

An augmenting path in a matching problem is closely related to the augmenting paths arising in maximum flow problems, paths along which one may increase the amount of flow between the terminals of the flow. It is possible to transform the bipartite matching problem into a maximum flow instance, such that the alternating paths of the matching problem become augmenting paths of the flow problem.[1] In fact, a generalization of the technique used in Hopcroft–Karp algorithm to arbitrary flow networks is known as Dinic's algorithm.

- Input: Bipartite graph

- Output: Matching

-

- repeat

-

maximal set of vertex-disjoint shortest augmenting paths

maximal set of vertex-disjoint shortest augmenting paths -

-

- until

Algorithm

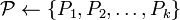

Let  and

and  be the two sets in the bipartition of

be the two sets in the bipartition of  , and let the matching from

, and let the matching from  to

to  at any time be represented as the set

at any time be represented as the set  .

.

The algorithm is run in phases. Each phase consists of the following steps.

- A breadth-first search partitions the vertices of the graph into layers. The free vertices in

are used as the starting vertices of this search, and form the first layer of the partition. At the first level of the search, only unmatched edges may be traversed (since the free vertices in

are used as the starting vertices of this search, and form the first layer of the partition. At the first level of the search, only unmatched edges may be traversed (since the free vertices in  are by definition not adjacent to any matched edges); at subsequent levels of the search, the traversed edges are required to alternate between matched and unmatched. That is, when searching for successors from a vertex in

are by definition not adjacent to any matched edges); at subsequent levels of the search, the traversed edges are required to alternate between matched and unmatched. That is, when searching for successors from a vertex in  , only unmatched edges may be traversed, while from a vertex in

, only unmatched edges may be traversed, while from a vertex in  only matched edges may be traversed. The search terminates at the first layer

only matched edges may be traversed. The search terminates at the first layer  where one or more free vertices in

where one or more free vertices in  are reached.

are reached. - All free vertices in

at layer

at layer  are collected into a set

are collected into a set  . That is, a vertex

. That is, a vertex  is put into

is put into  if and only if it ends a shortest augmenting path.

if and only if it ends a shortest augmenting path. - The algorithm finds a maximal set of vertex disjoint augmenting paths of length

. This set may be computed by depth first search from

. This set may be computed by depth first search from  to the free vertices in

to the free vertices in  , using the breadth first layering to guide the search: the depth first search is only allowed to follow edges that lead to an unused vertex in the previous layer, and paths in the depth first search tree must alternate between matched and unmatched edges. Once an augmenting path is found that involves one of the vertices in

, using the breadth first layering to guide the search: the depth first search is only allowed to follow edges that lead to an unused vertex in the previous layer, and paths in the depth first search tree must alternate between matched and unmatched edges. Once an augmenting path is found that involves one of the vertices in  , the depth first search is continued from the next starting vertex.

, the depth first search is continued from the next starting vertex. - Every one of the paths found in this way is used to enlarge

.

.

The algorithm terminates when no more augmenting paths are found in the breadth first search part of one of the phases.

Analysis

Each phase consists of a single breadth first search and a single depth first search. Thus, a single phase may be implemented in linear time.

Therefore, the first  phases, in a graph with

phases, in a graph with  vertices and

vertices and  edges, take time

edges, take time  .

.

It can be shown that each phase increases the length of the shortest augmenting path by at least one: the phase finds a maximal set of augmenting paths of the given length, so any remaining augmenting path must be longer. Therefore, once the initial  phases of the algorithm are complete, the shortest remaining augmenting path has at least

phases of the algorithm are complete, the shortest remaining augmenting path has at least  edges in it. However, the symmetric difference of the eventual optimal matching and of the partial matching M found by the initial phases forms a collection of vertex-disjoint augmenting paths and alternating cycles. If each of the paths in this collection has length at least

edges in it. However, the symmetric difference of the eventual optimal matching and of the partial matching M found by the initial phases forms a collection of vertex-disjoint augmenting paths and alternating cycles. If each of the paths in this collection has length at least  , there can be at most

, there can be at most  paths in the collection, and the size of the optimal matching can differ from the size of

paths in the collection, and the size of the optimal matching can differ from the size of  by at most

by at most  edges. Since each phase of the algorithm increases the size of the matching by at least one, there can be at most

edges. Since each phase of the algorithm increases the size of the matching by at least one, there can be at most  additional phases before the algorithm terminates.

additional phases before the algorithm terminates.

Since the algorithm performs a total of at most  phases, it takes a total time of

phases, it takes a total time of  in the worst case.

in the worst case.

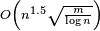

In many instances, however, the time taken by the algorithm may be even faster than this worst case analysis indicates. For instance, in the average case for sparse bipartite random graphs, Bast et al. (2006) (improving a previous result of Motwani 1994) showed that with high probability all non-optimal matchings have augmenting paths of logarithmic length. As a consequence, for these graphs, the Hopcroft–Karp algorithm takes  phases and

phases and  total time.

total time.

Comparison with other bipartite matching algorithms

For sparse graphs, the Hopcroft–Karp algorithm continues to have the best known worst-case performance, but for dense graphs a more recent algorithm by Alt et al. (1991) achieves a slightly better time bound,  . Their algorithm is based on using a push-relabel maximum flow algorithm and then, when the matching created by this algorithm becomes close to optimum, switching to the Hopcroft–Karp method.

. Their algorithm is based on using a push-relabel maximum flow algorithm and then, when the matching created by this algorithm becomes close to optimum, switching to the Hopcroft–Karp method.

Several authors have performed experimental comparisons of bipartite matching algorithms. Their results in general tend to show that the Hopcroft–Karp method is not as good in practice as it is in theory: it is outperformed both by simpler breadth-first and depth-first strategies for finding augmenting paths, and by push-relabel techniques.[2]

Non-bipartite graphs

The same idea of finding a maximal set of shortest augmenting paths works also for finding maximum cardinality matchings in non-bipartite graphs, and for the same reasons the algorithms based on this idea take  phases. However, for non-bipartite graphs, the task of finding the augmenting paths within each phase is more difficult. Building on the work of several slower predecessors, Micali & Vazirani (1980) showed how to implement a phase in linear time, resulting in a non-bipartite matching algorithm with the same time bound as the Hopcroft–Karp algorithm for bipartite graphs. The Micali–Vazirani technique is complex, and its authors did not provide full proofs of their results; subsequently,

a "clear exposition" was published by Peterson & Loui (1988) and alternative methods were described by other authors.[3] In 2012, Vazirani offerred a new simplified proof of the Micali-Vazirani algorithm.[4]

phases. However, for non-bipartite graphs, the task of finding the augmenting paths within each phase is more difficult. Building on the work of several slower predecessors, Micali & Vazirani (1980) showed how to implement a phase in linear time, resulting in a non-bipartite matching algorithm with the same time bound as the Hopcroft–Karp algorithm for bipartite graphs. The Micali–Vazirani technique is complex, and its authors did not provide full proofs of their results; subsequently,

a "clear exposition" was published by Peterson & Loui (1988) and alternative methods were described by other authors.[3] In 2012, Vazirani offerred a new simplified proof of the Micali-Vazirani algorithm.[4]

Pseudocode

/*

G = G1 ∪ G2 ∪ {NIL}

where G1 and G2 are partition of graph and NIL is a special null vertex

*/

function BFS ()

for v in G1

if Pair_G1[v] == NIL

Dist[v] = 0

Enqueue(Q,v)

else

Dist[v] = ∞

Dist[NIL] = ∞

while Empty(Q) == false

v = Dequeue(Q)

if Dist[v] < Dist[NIL]

for each u in Adj[v]

if Dist[ Pair_G2[u] ] == ∞

Dist[ Pair_G2[u] ] = Dist[v] + 1

Enqueue(Q,Pair_G2[u])

return Dist[NIL] != ∞

function DFS (v)

if v != NIL

for each u in Adj[v]

if Dist[ Pair_G2[u] ] == Dist[v] + 1

if DFS(Pair_G2[u]) == true

Pair_G2[u] = v

Pair_G1[v] = u

return true

Dist[v] = ∞

return false

return true

function Hopcroft-Karp

for each v in G

Pair_G1[v] = NIL

Pair_G2[v] = NIL

matching = 0

while BFS() == true

for each v in G1

if Pair_G1[v] == NIL

if DFS(v) == true

matching = matching + 1

return matching

Notes

References

- Ahuja, Ravindra K.; Magnanti, Thomas L.; Orlin, James B. (1993), Network Flows: Theory, Algorithms and Applications, Prentice-Hall.

- Alt, H.; Blum, N.; Mehlhorn, K.; Paul, M. (1991), "Computing a maximum cardinality matching in a bipartite graph in time

", Information Processing Letters 37 (4): 237–240, doi:10.1016/0020-0190(91)90195-N.

", Information Processing Letters 37 (4): 237–240, doi:10.1016/0020-0190(91)90195-N. - Bast, Holger; Mehlhorn, Kurt; Schafer, Guido; Tamaki, Hisao (2006), "Matching algorithms are fast in sparse random graphs", Theory of Computing Systems 39 (1): 3–14, doi:10.1007/s00224-005-1254-y.

- Blum, Norbert (2001), A Simplified Realization of the Hopcroft-Karp Approach to Maximum Matching in General Graphs, Tech. Rep. 85232-CS, Computer Science Department, Univ. of Bonn.

- Chang, S. Frank; McCormick, S. Thomas (1990), A faster implementation of a bipartite cardinality matching algorithm, Tech. Rep. 90-MSC-005, Faculty of Commerce and Business Administration, Univ. of British Columbia. As cited by Setubal (1996).

- Darby-Dowman, Kenneth (1980), The exploitation of sparsity in large scale linear programming problems – Data structures and restructuring algorithms, Ph.D. thesis, Brunel University. As cited by Setubal (1996).

- Edmonds, Jack (1965), "Paths, Trees and Flowers", Canadian J. Math 17: 449–467, doi:10.4153/CJM-1965-045-4, MR 0177907.

- Gabow, Harold N.; Tarjan, Robert E. (1991), "Faster scaling algorithms for general graph matching problems", Journal of the ACM 38 (4): 815–853, doi:10.1145/115234.115366.

- Hopcroft, John E.; Karp, Richard M. (1973), "An n5/2 algorithm for maximum matchings in bipartite graphs", SIAM Journal on Computing 2 (4): 225–231, doi:10.1137/0202019.

- Micali, S.; Vazirani, V. V. (1980), "An

algorithm for finding maximum matching in general graphs", Proc. 21st IEEE Symp. Foundations of Computer Science, pp. 17–27, doi:10.1109/SFCS.1980.12.

algorithm for finding maximum matching in general graphs", Proc. 21st IEEE Symp. Foundations of Computer Science, pp. 17–27, doi:10.1109/SFCS.1980.12. - Peterson, Paul A.; Loui, Michael C. (1988), "The general maximum matching algorithm of Micali and Vazirani", Algorithmica 3 (1-4): 511–533, doi:10.1007/BF01762129.

- Motwani, Rajeev (1994), "Average-case analysis of algorithms for matchings and related problems", Journal of the ACM 41 (6): 1329–1356, doi:10.1145/195613.195663.

- Setubal, João C. (1993), "New experimental results for bipartite matching", Proc. Netflow93, Dept. of Informatics, Univ. of Pisa, pp. 211–216. As cited by Setubal (1996).

- Setubal, João C. (1996), Sequential and parallel experimental results with bipartite matching algorithms, Tech. Rep. IC-96-09, Inst. of Computing, Univ. of Campinas.

- Vazirani, Vijay (2012), An Improved Definition of Blossoms and a Simpler Proof of the MV Matching Algorithm, CoRR abs/1210.4594.