Homotopy principle

In mathematics, the homotopy principle (or h-principle) is a very general way to solve partial differential equations (PDEs), and more generally partial differential relations (PDRs). The h-principle is good for underdetermined PDEs or PDRs, such as occur in the immersion problem, isometric immersion problem, and other areas.

The theory was started by Yakov Eliashberg, Mikhail Gromov and Anthony V. Phillips. It was based on earlier results that reduced partial differential relations to homotopy, particularly for immersions. The first evidence of h-principle appeared in the Whitney–Graustein theorem. This was followed by the Nash-Kuiper Isometric  embedding theorem and the Smale-Hirsch Immersion theorem.

embedding theorem and the Smale-Hirsch Immersion theorem.

Rough idea

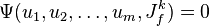

Assume we want to find a function ƒ on Rm which satisfies a partial differential equation of degree k, in co-ordinates  . One can rewrite it as

. One can rewrite it as

where  stands for all partial derivatives of ƒ up to order k. Let us exchange every variable in

stands for all partial derivatives of ƒ up to order k. Let us exchange every variable in  for new independent variables

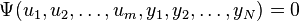

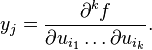

for new independent variables  Then our original equation can be thought as a system of

Then our original equation can be thought as a system of

and some number of equations of the following type

A solution of

is called a non-holonomic solution, and a solution of the system (which is a solution of our original PDE) is called a holonomic solution.

In order to check whether a solution exists, first check if there is a non-holonomic solution (usually it is quite easy and if not then our original equation did not have any solutions).

A PDE satisfies the h-principle if any non-holonomic solution can be deformed into a holonomic one in the class of non-holonomic solutions. Thus in the presence of h-principle, a differential topological problem reduces to an algebraic topological problem. More explicitly this means that apart from the topological obstruction there is no other obstruction to the existence of a holonomic solution. The topological problem of finding a non-holonomic solution is much easier to handle and can be addressed with the obstruction theory for topological bundles.

Many underdetermined partial differential equations satisfy the h-principle. However, the falsity of an h-principle is also an interesting statement, intuitively this means the objects being studied have non-trivial geometry that cannot be reduced to topology. As an example, embedded Lagrangians in a symplectic manifold do not satisfy an h-principle, to prove this one needs to find invariants coming from pseudo-holomorphic curves.

Simple examples

Monotone functions

Perhaps the simplest partial differential relation is for the derivative to not vanish:  Properly, this is an ordinary differential relation, as this is a function in one variable. These are the strictly monotone differentiable functions, either increasing or decreasing, and one may ask the homotopy type of this space, as compared with spaces without this restriction. The space of (differentiable, strictly) monotone functions on the real line consists of two disjoint convex sets: the increasing ones and the decreasing ones, and has the homotopy type of two points. The space of all functions on the real line is a convex set, and has the homotopy type of one point. This does not appear promising – they have not even the same components – but closer examination reveals that this is the only problem: all of the higher homotopy groups agree. If instead one restricts to all maps with given endpoint values:

Properly, this is an ordinary differential relation, as this is a function in one variable. These are the strictly monotone differentiable functions, either increasing or decreasing, and one may ask the homotopy type of this space, as compared with spaces without this restriction. The space of (differentiable, strictly) monotone functions on the real line consists of two disjoint convex sets: the increasing ones and the decreasing ones, and has the homotopy type of two points. The space of all functions on the real line is a convex set, and has the homotopy type of one point. This does not appear promising – they have not even the same components – but closer examination reveals that this is the only problem: all of the higher homotopy groups agree. If instead one restricts to all maps with given endpoint values: ![f\colon [0,1]\to {\mathbf {R}}](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/2/4/7/0/2470de26153f2aea761b71f52f32d575.png) such that

such that  and

and  , then for

, then for  the inclusion of functions with non-vanishing derivative in all continuous functions is a homotopy equivalence – both the spaces are convex, and in fact the monotone functions are a convex subset. Further, there is a natural base point, namely the linear function

the inclusion of functions with non-vanishing derivative in all continuous functions is a homotopy equivalence – both the spaces are convex, and in fact the monotone functions are a convex subset. Further, there is a natural base point, namely the linear function  – this is the function with shortest path length in this space.

– this is the function with shortest path length in this space.

While this is a very simple example, it illustrates some of the general aspects of h-principles:

- The lowest homotopy groups – showing that the inclusion is 0-connected or 1-connected – is hardest;

- h-principles are largely about showing that higher homotopy groups agree (rather, that the inclusion is an isomorphism on these groups) – showing that, once an inclusion has been shown to be 1-connected, it is in fact n-connected, possibly for all n;

- h-principles can sometimes be shown by variational methods, as in the above length example.

This example also extends to significant results:

extending this to immersions of a circle into itself classifies them by order (or winding number), by lifting the map to the universal covering space and applying the above analysis to the resulting monotone map – the linear map corresponds to multiplying angle:  (

( in complex numbers). Note that here there are no immersions of order 0, as those would need to turn back on themselves. Extending this to circles immersed in the plane – the immersion condition is precisely the condition that the derivative does not vanish – the Whitney–Graustein theorem classified these by turning number by considering the homotopy class of the Gauss map and showing that this satisfies an h-principle; here again order 0 is more complicated.

in complex numbers). Note that here there are no immersions of order 0, as those would need to turn back on themselves. Extending this to circles immersed in the plane – the immersion condition is precisely the condition that the derivative does not vanish – the Whitney–Graustein theorem classified these by turning number by considering the homotopy class of the Gauss map and showing that this satisfies an h-principle; here again order 0 is more complicated.

Smale's classification of immersions of spheres as the homotopy groups of Stiefel manifolds, and Hirsch's generalization of this to immersions of manifolds being classified as homotopy classes of maps of frame bundles are much further-reaching generalizations, and much more involved, but similar in principle – immersion requires the derivative to have rank k, which requires the partial derivatives in each direction to not vanish and to be linearly independent, and the resulting analog of the Gauss map is a map to the Stiefel manifold, or more generally between frame bundles.

A car in the plane

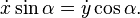

As another simple example, consider a car moving in the plane. The position of a car in the plane is determined by three parameters: two coordinates  and

and  for the location (a good choice is the location of the midpoint between the back wheels) and an angle

for the location (a good choice is the location of the midpoint between the back wheels) and an angle  which describes the orientation of the car. The motion of the car satisfies the equation

which describes the orientation of the car. The motion of the car satisfies the equation

since a non-skidding car must move in the direction of its wheels. In robotics terms, not all paths in the task space are holonomic.

A non-holonomic solution in this case, roughly speaking, corresponds to a motion of the car by sliding in the plane. In this case the non-holonomic solutions are not only homotopic to holonomic ones but also can be arbitrarily well approximated by the holonomic ones (by going back and forth, like parallel parking in a limited space) – note that this approximates both the position and the angle of the car arbitrarily closely. This implies that, theoretically, it is possible to parallel park in any space longer than the length of your car. It also implies that, in a contact 3 manifold, any curve is  -close to a Legendrian curve.

This last property is stronger than the general h-principle; it is called the

-close to a Legendrian curve.

This last property is stronger than the general h-principle; it is called the  -dense h-principle.

-dense h-principle.

While this example is simple, compare to the Nash embedding theorem, specifically the Nash–Kuiper theorem, which says that any short smooth ( ) embedding or immersion of

) embedding or immersion of  in

in  or larger can be arbitrarily well approximated by an isometric

or larger can be arbitrarily well approximated by an isometric  -embedding (respectively, immersion). This is also a dense h-principle, and can be proven by an essentially similar "wrinkling" – or rather, circling – technique to the car in the plane, though it is much more involved.

-embedding (respectively, immersion). This is also a dense h-principle, and can be proven by an essentially similar "wrinkling" – or rather, circling – technique to the car in the plane, though it is much more involved.

Ways to prove the h-principle

- Removal of Singularities technique developed by Gromov and Eliashberg

- Sheaf technique based on the work of Smale and Hirsch.

- Convex integration based on the work of Nash and Kuiper

Some paradoxes

Here we list a few counter-intuitive results which can be proved by applying the h-principle:

- Cone Eversion.[1] Let us consider functions f on R2 without origin f(x) = |x|. Then there is a continuous one-parameter family of functions

such that

such that  ,

,  and for any

and for any  ,

,  is not zero at any point.

is not zero at any point.

- Any open manifold admits a (non-complete) Riemannian metric of positive (or negative) curvature.

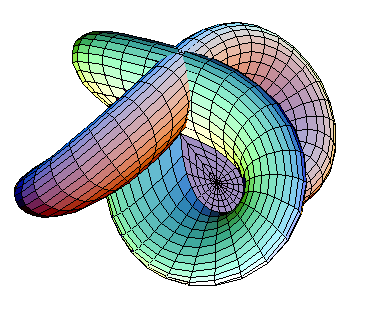

- Smale's paradox can be done using

isometric embedding of

isometric embedding of  .

.

References

- Masahisa Adachi, Embeddings and immersions, translation Kiki Hudson

- Y. Eliashberg, N. Mishachev, Introduction to the h-principle

- Gromov, M. (1986), Partial differential relations, Springer, ISBN 3-540-12177-3

- M. W. Hirsch, Immersions of manifold. Trans. Amer. Math. Soc. 93 (1959)

- N. Kuiper, On

Isometric Imbeddings I, II. Nederl. Acad. Wetensch. Proc. Ser A 58 (1955)

Isometric Imbeddings I, II. Nederl. Acad. Wetensch. Proc. Ser A 58 (1955) - John Nash,

Isometric Imbedding. Ann. of Math(2) 60 (1954)

Isometric Imbedding. Ann. of Math(2) 60 (1954) - S. Smale, The classification of immersions of spheres in Euclidean spaces. Ann. of Math(2) 69 (1959)

- David Spring, Convex integration theory - solutions to the h-principle in geometry and topology, Monographs in Mathematics 92, Birkhauser-Verlag, 1998

- ↑ D. Fuchs, S. Tabachnikov, Mathematical Omnibus: Thirty Lectures on Classic Mathematics