Homer Davenport

| Homer Davenport | |

|---|---|

Davenport in 1912 | |

| Born |

March 8, 1867 Waldo Hills, Oregon, U.S. |

| Died |

May 2, 1912 (aged 45) New York, New York, U.S. |

| Occupation | Political cartoonist |

| Known for | Political cartoons, Arabian horse breeder |

| Spouse(s) | Daisy Moor (married 1893, separated 1909) |

| Children | Homer Clyde, Mildred, and Gloria |

| Relatives | Ralph Carey Geer |

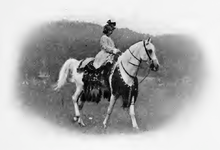

Homer Calvin Davenport (March 8, 1867 – May 2, 1912) was a political cartoonist and writer from the United States. He is known for drawings that satirized figures of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, most notably Ohio Senator Mark Hanna. Although Davenport had no formal art training, he became one of the highest paid political cartoonists in the world. Davenport also was one of the first major American breeders of Arabian horses and one of the founders of the Arabian Horse Club of America.

A native Oregonian, Davenport developed interests in both art and horses as a young boy. He tried a variety of jobs before gaining employment as a cartoonist, initially working at several newspapers on the West Coast, including The San Francisco Examiner, purchased by William Randolph Hearst. His talent for drawing and interest in Arabian horses dovetailed in 1893 at the Chicago Daily Herald when he studied and drew the Arabian horses exhibited at the World's Columbian Exposition. When Hearst obtained the New York Morning Journal in 1895, money was no object in his attempt to establish the Journal as a leading New York newspaper, and Hearst moved Davenport east in 1885 to be part of what is regarded as one of the greatest newspaper staffs ever assembled. Working with columnist Alfred Henry Lewis, Davenport created many cartoons in opposition to the 1896 Republican presidential candidate, former Ohio governor William McKinley, and Hanna, his campaign manager. McKinley was elected and Hanna elevated to the Senate; Davenport continued to draw his sharp cartoons during the 1900 presidential race, though McKinley was again victorious.

In 1904, Davenport was hired away from Hearst by the New York Evening Mail, a Republican paper, and there drew a favorable cartoon of President Theodore Roosevelt that boosted Roosevelt's election campaign that year. The President in turn proved helpful to Davenport in 1906 when the cartoonist required diplomatic permission to travel abroad in his quest to purchase pure desertbred Arabian horses. In partnership with millionaire Peter Bradley, Davenport traveled extensively amongst the Anazeh people of Syria and went through a brotherhood ceremony with the Bedouin leader who guided his travels. The 27 horses Davenport purchased and brought to America had a profound and lasting impact on Arabian horse breeding. Davenport's later years were marked by fewer influential cartoons and a troubled personal life; he dedicated much of his time to his animal breeding pursuits, traveled widely, and gave lectures. He was a lifelong lover of animals and of country living; he not only raised horses, but also exotic poultry and other animals. He died in 1912 of pneumonia, which he contracted after going to the docks of New York City to watch and chronicle the arrival of survivors of the Titanic.

Childhood and early career

Davenport was born in 1867 in the Waldo Hills, several miles south of Silverton, Oregon. His parents were Timothy W. and Florinda Geer Davenport.[8] He had an older sister, Orla, and his parents had previously lost two other children in infancy.[9] Timothy Davenport was one of the founders of the Republican Party in Oregon and served as an Oregon state representative, state senator, and an Indian agent. He ran unsuccessfully for the United States House of Representatives in 1874.[8] Florinda was an admirer of the political cartoons of Thomas Nast that appeared in Harper's Weekly. While pregnant with Homer, she developed a belief, which she viewed as a prophecy, that her child would become as famous a cartoonist as Nast. She was also influenced by the essay "How To Born [sic] A Genius," by Russell Trall, and closely followed his recommendations for diet and "concentration" during her pregnancy. She died of smallpox in 1870, when Homer was three years old, and on her deathbed asked her husband to give Homer "every opportunity" to become a cartoonist.[6][10]

Young Davenport was given a box of paints as a Christmas gift. At this stage of his youth, as his father later stated, Homer also had "horse on the brain," and, cooped up inside during the winter of 1870–1871, Timothy told Homer stories of Arab people and their horses. Soon after, at the age of three years and nine months, the boy used his paints to produce an image he called "Arabian horses."[11] He learned to ride on the family's pet horse, Old John.[12] Following his mother's death, both of Davenport's grandmothers helped raise him.[13] When he was seven, he and his father moved to Silverton—the cartoonist later recounted that the move to the community, about 40 miles (64 km) south of Portland and with a population of 300 at the time, was so he "might live in the Latin Quarter of that village and inhale any artistic atmosphere that was going to waste".[14]

Homer began to study music,[15] and was allowed to help Timothy clerk at the store the elder Davenport purchased when he first moved to Silverton.[16] Timothy required Homer to milk the cows, but otherwise Homer was to "study faces and draw."[6] He was well-liked by the villagers, but they considered him shiftless—they did not consider drawing to be real work. He exhibited a love of animals, especially fast horses and fighting cocks.[14] Davenport later wrote that his fascination with Arabian horses was reawakened in his adolescent years with his admiration of a picture of an Arabian-type horse found on an empty can of horse liniment. He carefully cleaned the can and kept it as his "only piece of artistic furniture" for many years until forced to leave it behind when he moved to San Francisco.[17] He also played in the community band in his formative years, and with that group young Davenport once traveled as far as Portland.[18]

Davenport's initial jobs were not successful. His first position outside Silverton began when a small circus came to town, and Davenport, in his late teenage years, left with it. He was assigned as a clown and to care for the circus's small herd of horses, which he also sketched. He became disenchanted with the circus when he was told to brush the elephant's entire body with linseed oil, a difficult task. He left the tour and tried to succeed as a jockey, despite being tall.[lower-alpha 1] Other early positions included clerking in a store and working as a railway fireman.[14] Although his work took him from Silverton, for the remainder of his life, Davenport was often melancholy for his native Oregon, and in writing to relatives there, he repeatedly told them not to send him anything that would remind him of Silverton, because he would be plunged into despair.[19]

Newspaper career

West Coast years

Davenport's first job in journalism, in 1889, was drawing for the Portland newspaper, The Oregonian, where he showed a talent for sketching events from memory. He was fired in 1890, it was said, for poorly drawing a stove for an advertisement—he could not draw buildings and appliances well. By another story, he was let go when there was only work for one in the paper's engraving department, and he was junior man. He then worked for the Portland Mercury, traveling to New Orleans for a prizefight in January 1891, and, when he returned, earned money through selling his drawings as postcards.[10][20]

Davenport's talent came to the attention of C.W. Smith, general manager of the Associated Press, and also Timothy Davenport's first cousin. Smith got the young cartoonist a free pass on the railroad to San Francisco in 1891 and wrote a letter to the business manager of The San Francisco Examiner, essentially a demand that Davenport be hired. He was; the Examiner's business manager had been greatly impressed by doodles that Davenport drew while waiting.[21] At the Examiner, Davenport was not a cartoonist, but a newspaper artist who illustrated articles—the technology to directly reproduce photographs in newspapers was still a few years away.[22] After a year at the Examiner, he was fired; several stories state that this occurred after he asked for a raise from his meager salary of $10 per week.[23]

His work, including the New Orleans postcards, had attracted admirers, who, in addition to Smith, helped him to get a job with the San Francisco Chronicle in 1892. While there, he attracted reader attention for his ability to draw animals. He resigned in April 1893 because he wanted to go to Chicago and see the World's Columbian Exposition, and his contacts secured him a position with the Chicago Daily Herald.[24] At the Herald, one of his jobs was to illustrate the horse races at Washington Park.[25] He was dismissed from the Herald, and in one account ascribed his dismissal to going every day to visit and sketch the Arabian horses on exhibit at the World's Fair.[26] However, more likely, the poor economy and the end of the fair caused the Herald to lay him off,[24] and Davenport suggested as much in a 1905 interview.[27] While at the Daily Herald, he married San Francisco's Daisy Moor, who traveled to Chicago to marry him.[28]

Davenport returned to San Francisco and regained his position at the Chronicle. This time, he was allowed to caricature California political figures. By then, William Randolph Hearst owned the Examiner. In his early days as a newspaper tycoon, Hearst followed Davenport's cartoons in the Chronicle, and when the cartoonist became well-known for his satires of figures in the 1894 California gubernatorial campaign, hired him, more than doubling his salary.[29] When a famous horse died and the Examiner lacked an image, Davenport, who had seen the animal the previous year, drew it from memory. Impressed, Hearst purchased the original drawing. Davenport took his responsibilities as political cartoonist seriously, traveling to Sacramento, the state capital, to observe the legislative process and its participants.[22]

Transfer to New York Journal

Hearst had been successful in California with the Examiner, and sought to expand operations to the nation's largest city, New York. Several newspapers were available for sale, including The New York Times, but Hearst then lacked the resources to purchase them. In September 1895, having lost most of its circulation and its advertisers over the past year, Cincinnati publisher John R. McLean made his New York Morning Journal available at a price within Hearst's means, and he bought it for $180,000.[30] Hearst changed the name to the New York Journal and began to assemble what Hearst biographer Ben Procter deemed one of the greatest staffs in newspaper history. Under editor-in-chief Willis J. Abbot, the well paid staff included foreign correspondent Richard Harding Davis, columnist Alfred Henry Lewis, and humorist Bill Nye. Contributors included Mark Twain and Stephen Crane. Davenport was among a number of talented staff on the Examiner whom Hearst transferred to New York and employed on the Journal at a high salary.[31]

In 1896, a presidential election year, Davenport was sent to Washington to meet and study some of the Republican Party's potential candidates, such as Speaker of the House Thomas B. Reed. Hearst's Journal was a Democratic paper, and Davenport would be expected to harshly caricature the Republican presidential candidate. The Republicans were anxious to take over the White House from Democrat Grover Cleveland;[32] they were widely expected to do so, as the Democrats were blamed for the economic Panic of 1893, which had brought depression to the nation for the past three years. None of the potential Democratic candidates seemed particularly formidable, and the Republican nominee was expected to win in a landslide.[33]

Reporters and illustrators on the Journal often worked in pairs. Davenport was teamed with Lewis and the two soon forged a solid relationship. In early 1896, Lewis went to Ohio to investigate the leading candidate for the Republican presidential nomination, that state's former governor, William McKinley. To interview the candidate, Lewis was required to undergo an interview himself, with McKinley's political manager, Cleveland industrialist Mark Hanna. Hanna had set aside his business career to manage McKinley's campaign, and was paying all expenses for a political machine which helped make McKinley the frontrunner in the Republican race. Lewis got his interview with McKinley, then remained in Ohio, investigating Hanna. In 1893, Governor McKinley had been called upon to pay the obligations of a friend for whom he had co-signed loans; Hanna and other McKinley supporters had bought up or paid these debts. Lewis viewed Hanna as controlling McKinley, able to ruin the candidate by calling in the purchased notes. Becoming increasingly outraged by what he deemed as Hanna's purchase of the Republican nomination, and so likely the presidency, Lewis began to popularize this view in the pages of the Journal. The first Davenport cartoon depicting Hanna appeared soon after.[34]

1896 election and Mark Hanna

McKinley, with the exception of his 1893 financial crisis, had avoided scandal and carefully guarded his image, making him difficult to attack. Hanna proved an easier target.[35] Although Davenport had depicted Hanna in his cartoons before the Republican convention in June, these efforts were uninspired.[36] This changed once Davenport got a look at his subject while attending the 1896 Republican National Convention in St. Louis. After three days spent closely observing Hanna managing the convention to secure McKinley's nomination and passage of a platform supporting the gold standard, Davenport was impressed with Hanna's dynamic behavior. Convinced that he could effectively lampoon Hanna, Davenport's cartoons became more effective.[37] Hanna was a tall man; Davenport exaggerated this trait, in part by shrinking everybody else. He also increased Hanna's already substantial girth. Hanna's short sideburns were lengthened and made rougher—Davenport described them as "like an unplaned cedar board". Davenport borrowed from the animal kingdom for his creation, drawing Hanna's ears so they stuck out like a monkey's. The cartoonist described Hanna's eyes as like a parrot's, leaving no movement unseen, or as those of a circus elephant—scanning the street for peanuts.[36]

The resultant caricature of Hanna was given props such as moneybags and laborer's skulls to rest his feet upon, as well as cufflinks engraved with the dollar sign to wear with his plaid businessman's suits. He was often accompanied by William McKinley, usually drawn as a shrunken though dignified figure dominated by the giant Hanna. Even so, Davenport felt the figure seemed to lack something until the cartoonist took the dollar signs from the cufflink and placed them inside every check of the cartoon Hanna's suit. Davenport likely acted at the suggestion of his cartoonist colleague at the Journal, M. de Lipman, who had depicted McKinley as Buddha in a loincloth with Hanna as his attendant, robes ablaze with an array of dollar signs. According to Hearst biographer Kenneth Whyte, "whatever its origins, Davenport's 'plutocratic plaid', as it became known, was an instant hit."[38]

In July 1896, the Democrats nominated former Nebraska congressman William Jennings Bryan for president. Bryan had electrified the Democratic National Convention with his Cross of Gold speech. Bryan was an eloquent supporter of "free silver", a policy which would inflate the currency by allowing silver bullion to be submitted by the public and converted into coins even though the intrinsic value of a silver dollar was about half its stated value. Bryan's candidacy divided the Democratic Party and its supporters, and caused many normally-Democratic papers to abandon him. Hearst called a meeting of his senior staff to decide the Journal's policy. Though few favored the Democrat, Hearst decided, "Unlimber the guns; we are going to fight for Bryan."[39]

Davenport's cartoons had an effect on Hanna. West Virginia Senator Nathan B. Scott remembered being with Hanna as he viewed his caricature wearing a suit covered with dollar signs, trampling women and children underfoot, and hearing the Ohioan state, "that hurts".[40] Hanna could not make public appearances without having to field questions about the cartoons.[41] Nevertheless, publisher J.B. Morrow, a friend of both McKinley and his campaign manager, stated that Hanna "took his course regardless of local criticism".[42] McKinley made no attempt to deflect criticism from Hanna and in fact kept a file of Davenport cartoons that particularly amused him. Despite Hanna's discomfiture, both men were content to have Hanna attacked if it meant that McKinley would not be.[43]

Most of the cartoons Davenport drew during the 1896 campaign were simple in execution and somber in mood. One, for example, depicts Hanna walking down Wall Street, bags of money in each hand and a grin on his face. Another shows only Hanna's hand and wrist—and McKinley dangling from his fob chain. One that is intended to be funny depicts McKinley as a small boy accompanied by Hanna as nursemaid; McKinley tugs at Hanna's skirts, wanting to go into a shop where the labor vote is for sale.[41] Another shows Hanna wearing a Napoleon hat (McKinley was said to resemble the late emperor), raising a mask of McKinley's face to his own.[44]

|

Davenport's cartoons ran a few times per week in the Journal, generally on an inside page. They were, however, widely reprinted—including in Bryan's campaign materials—and according to Whyte, "nothing in any paper came close to matching their impact [on the presidential race]".[41] Hanna biographer William T. Horner noted, "Davenport's image of Hanna in a suit covered with dollar signs remains an iconic view of the man to this day".[45]

Despite great public excitement after his nomination,[46] Bryan was unable to overcome his disadvantages in financing, organization, lack of party unity, and public mistrust of the Democrats, and he was defeated in the November election.[47] A few days after the election, Davenport went to Republican headquarters in New York to be formally introduced to the man he had so sharply characterized. As witnesses such as Vice President-elect Garret Hobart came in to see the good-humored proceedings, Hanna told Davenport, "I admire your genius and execution, but damn your conception."[48]

With the 1896 campaign over, a reporter asked Davenport in February 1897 who would replace Hanna as a special subject of his cartoons, and Davenport replied, "Hanna is by no means out of the way. He will probably continue a good subject for some time."[49] Hanna, having declined the position of Postmaster General, secured appointment to the Senate when McKinley made Ohio's aging senior senator, John Sherman, his Secretary of State. Until 1913, state legislatures, not the people, elected senators, and so Hanna had to seek election to a full term when the Ohio General Assembly met in January 1898. Hanna campaigned in the 1897 legislative election, and was elected to the Senate in his own right the following January, in a very close vote. Davenport drew cartoons against Hanna in the senatorial race. Nevertheless, when he attended the legislature's meeting in Columbus, he wore a Hanna button, and seemed happy after Hanna's triumph. When asked why, he replied, "that insures me six more years at him, and he's a good subject".[50][51]

1897 to 1901

... there is no weapon so potential as the pencil of Nast and Davenport. It supplies the place of conscience to many a pachydermatous sinner. He may be indifferent to God and the devil; regardless of heaven and hell; careless of the sanctions of human law so long as be can escape the penitentiary or the gibbet; but he shrinks from the pillory of the cartoon in which he is a fixed figure to be pointed at by the slow unmoving finger of public scorn."

The 1896 campaign made Davenport famous and well paid, earning $12,000 per year, the highest compensation of any cartoonist of his time. Hearst, who had lost a fortune but who had established the Journal as one of New York's most influential newspapers, also gave him a $3,000 bonus with which to take a trip to Europe with Daisy. In London, Davenport interviewed and drew the elderly former prime minister, William Gladstone. In Venice, he came upon a large statue of Samson.[53] He was impressed by the large muscles of the work, and immediately conceived of it as representing America's powerful corporate trusts, the status of which was then a major political issue. A large, powerful, grass-skirted figure representing the trusts would be seen with McKinley and Hanna in Davenport's cartoons during the President's re-election bid in 1900.[53]

In 1897, Davenport was sent to Carson City, Nevada, to cover the heavyweight championship fight between boxers Bob Fitzsimmons and Jim Corbett, a match heavily promoted by the Journal. Fitzsimmons won. Davenport traveled to Nevada by way of Silverton, visiting there for the first time since becoming famous. The following year, Davenport went to Asbury Park, New Jersey, to watch Corbett in training. Davenport both interviewed him and made several drawings which the Journal published, including one of cartoonist and boxer sparring.[54]

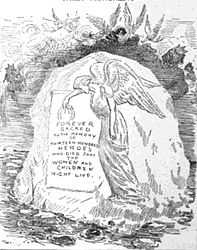

Davenport's drawings left few public figures unscathed; he even caricatured himself and his boss, Hearst. Ultimately, Davenport's work became so well recognized for skewering political figures he considered corrupt, that in 1897 his opponents attempted to pass a law banning political cartoons in New York. The bill, introduced in the state legislature with the prodding of U.S. Senator Thomas C. Platt, (R-NY), did not pass, but the effort inspired Davenport to create one of his most famous works: "No Honest Man Need Fear Cartoons."[55]

|

In 1897 and into 1898, the Hearst papers pounded a drumbeat for war with Spain. Davenport drew cartoons depicting President McKinley as cowardly and unwilling to go to war because it might harm Wall Street.[56] Once the Spanish–American War was under way, one of the American war heroes was Admiral George Dewey, victor at the Battle of Manila Bay, who was welcomed home in 1899 with celebrations and the gift of a house. The admiral promptly deeded the residence over to his newly–wed wife, a Catholic, turning public opinion (especially among Protestants) against him. However, resentment eased after Davenport depicted Dewey on his bridge during the battle, with the caption, "Lest we forget".[57]

In 1899, Davenport returned to Europe, covering the Dreyfus case in Rennes.[53] In 1900, the presidential election again featured McKinley defeating Bryan, and again featured Davenport, reprising his depictions of Hanna, this time aided by the giant figure of the trusts. Also a subject of Hearst's cartoonists was McKinley's running mate, war hero and New York Governor Theodore Roosevelt, presented as a child with a Rough Rider's outfit and little self-control.[58][59]

1901 to 1912

The Journal was renamed the American in 1901. Davenport continued there until 1904, eventually earning $25,000 per year, a very large salary at the time. Following Hearst's policy, he relentlessly attacked President Roosevelt, who had succeeded the assassinated McKinley in September 1901. Davenport both cartooned and wrote for the American; one column mockingly alleged that the new President had hidden all portraits of previous presidents in the White House basement, with the visitor left to view a large portrait of Roosevelt as well-armed Rough Rider.[60]

Nevertheless, the Republicans wooed Davenport, seeking to deprive the Democrats of one of their weapons, and eventually President and cartoonist met. In 1904, Davenport left the American for the New York Evening Mail, a Republican paper, to be paid $25,000 for the final six months of 1904 (most likely paid by the party's backers) and an undisclosed salary after that. The 1904 presidential campaign featured Roosevelt, seeking a full term in his own right, against the Democratic candidate, Judge Alton B. Parker of New York. Again Davenport affected the campaign, this time with a cartoon of Uncle Sam with his hand on Roosevelt's shoulder, "He's good enough for me".[60] The Republicans spent $200,000 reproducing it;[60] the image was used as cover art on sheet music for marches written in support of Roosevelt.[61][62]

Although Davenport continued at the Evening Mail after Roosevelt was elected, the quality of his work declined; fewer and fewer of his images were selected for inclusion in Albert Shaw's Review of Reviews. He also began to devote large periods to other activities; in 1905, he spent months in his home state of Oregon, first visiting Silverton and then showing, at Portland's Lewis and Clark Exposition, the animals he bred.[63]

|

Beginning in 1905, Davenport traveled on the Chatauqua lecture circuit, giving engaging talks, during which he sketched on stage. He sometimes appeared on the same program as Bryan, though on different days, and like him drew thousands of listeners.[64] In 1906, he traveled to the Middle East to purchase Arabian horses from their native land, and then wrote a book about his experiences.[65] Davenport authored an autobiographical book, The Diary of a Country Boy, and collections of his cartoons, including The Dollar or the Man[10] and Cartoons by Davenport. Apparently as a joke, Davenport once included The Belle (or sometimes, Bell ) of Silverton and Other Oregon Stories in a list of his publications, and reference books for years listed it among his works. A book of that name did not exist, however. Some speculate that this was an early working title for The Country Boy.[66]

Davenport's marriage had failed by 1909, and he suffered a breakdown that year, related to his ongoing divorce case. As he recovered, he announced a forthcoming series to be available for license to newspapers, "Men I have sketched". This project was aborted when, in 1911, Davenport was invited by Hearst to return to the American.[67] He was on assignment for the American on April 19, 1912, when he met the RMS Carpathia at the docks in New York to draw the survivors of the RMS Titanic. He drew three cartoons, but upon leaving his office was in a "highly nervous state".[68] That evening he fell ill at the apartment of a friend, Mrs. William Cochran, a medium and spiritualist. Diagnosed with pneumonia, he died in her home two weeks later, on May 2, 1912.[68] Hearst paid for eight doctors to treat Davenport, and later for an elaborate funeral—the publisher had Davenport's body returned to his beloved Silverton for burial. Addison Bennett of The Oregonian wrote, "Yes, Homer has come home for the last time, home to wander again never".[69]

Arabian horse breeder

In addition to his cartooning, Davenport is remembered for playing a key role in bringing some of the earliest desertbred or asil Arabian horses to America. A longtime admirer of horses, Davenport stated in 1905, "I have dreamed of Arabian horses all my life."[70] He had been captivated by the beauty of the Arabians brought to the Chicago Columbian Exposition in 1893.[71] Upon learning that these horses had remained in America and had been sold at auction, he sought them out,[65] finding most of the surviving animals in 1898[70] in the hands of millionaire fertilizer magnate Peter Bradley of Hingham, Massachusetts.[72] Davenport bought some Arabian horses outright between 1898 and 1905, paying $8,500 for one stallion,[70] but he later partnered with Bradley in the horse business.[73] Among his purchases, he managed to gather all but one of the surviving horses that had been a part of the Chicago Exhibition.[74]

Desert journey

In 1906, Davenport, with Bradley's financial backing,[75] used his political connections, particularly those with President Theodore Roosevelt, to obtain the diplomatic permissions required to travel into the lands controlled by the Ottoman Empire.[76] Roosevelt himself was interested in breeding quality cavalry horses, had tried but failed to get Congress to fund a government cavalry stud farm, and considered Arabian blood useful for army horses.[77] Davenport originally intended to travel alone, but was soon joined by two young associates anxious for an adventure in the Middle East: C.A. "Arthur" Moore, Jr., and John H. "Jack" Thompson, Jr.[74] He traveled throughout what today is Syria and Lebanon, and successfully brought 27 horses to America.[76]

To travel to the Middle East and purchase horses, Davenport needed to obtain diplomatic permission from the government of the Ottoman Empire,[76] and specifically from Sultan Abdul Hamid II.[78] In December 1905, Davenport approached President Roosevelt for help, and in January 1906, Roosevelt provided him a letter of support that he was able to present to the Turkish Ambassador to the United States, Chikeb Bey, who contacted the Sultan. To the surprise of both Davenport and the Ambassador, the permit, called an Iradé, was granted, allowing the export of "six or eight" horses.[79] Davenport and his traveling companions left the United States on July 5, 1906, traveling to France by ship and from there to Constantinople by train.[74] Upon arrival, the Iradé was authenticated, and clarified that Davenport would be allowed to export both mares and stallions.[80] Davenport's accomplishment was notable for several reasons. It was the first time Arabian horses officially had been allowed to be exported from the Ottoman Empire in 35 years.[81] It was also notable that Davenport not only was able to purchase stallions, which were often available for sale to outsiders,[82] but also mares, which were treasured by the Bedouin; the best war mares generally were not for sale at any price.[83]

Before Davenport left Constantinople to travel to Aleppo and then into the desert, he visited the royal stables,[84] and also took advantage of an opportunity to view the Sultan during a public appearance.[85] He displayed his artistic ability and talent for detail by sketching several portraits of Abdul Hamid II from memory about a half-hour after observing him, as Davenport believed the ruler unwilling to have his image drawn.[86] Davenport's personal impression of the Sultan was sympathetic, viewing him as a frail, elderly man burdened by the weight of his office but kind and fatherly to his children. Davenport compared his appearance as a melding of the late congressman from Maine, Nelson Dingley, with merchant and philanthropist Nathan Straus, commenting of the Sultan, "I thought ... that no matter what crimes had been charged to him, his expressionless soldiers, his army and its leaders were possibly more to blame than he."[87] Believing that he needed to keep his sketches a secret, he carried the sketch book in a hidden pocket throughout his journey, and at customs smuggled it onto the steamer home hidden inside a bale of hay.[88]

One reason for Davenport's success in obtaining high-quality, pure-blooded Arabian horses was his (possibly accidental) decision to breach protocol and visit Akmet Haffez, a Bedouin who served as a liaison between the Ottoman government and the tribal people of the Anazeh, before calling upon the Governor of Syria, Nazim Pasha. Haffez considered the timing of Davenport's visit a great honor, and gave Davenport his finest mare, a war mare named *Wadduda.[lower-alpha 2] Not to be outdone, the Pasha gave Davenport the stallion *Haleb,[lower-alpha 2] who was a well-respected sire throughout the region, known as the "Pride of the Desert."[73][89] Haleb had been given to the Pasha as a reward for keeping the camel tax low.[90] Haffez then personally escorted Davenport into the desert, and at one point in the journey the two men took an oath of brotherhood.[91] Haffez helped arrange for the best-quality horses to be presented, negotiated fair prices, and verified that their pedigrees were asil.[73] Davenport chronicled this journey in his 1908 book, My Quest of the Arabian Horse.[92]

The impact of the 17 stallions and 10 mares purchased by Davenport was of major importance to the Arabian horse breed in America.[93] While what are now called "Davenport" bloodlines can be found in thousands of Arabian horse pedigrees, there are also some preservation breeders whose horses have bloodlines that are entirely descended from the horses he imported.[94] Davenport's efforts, as well as those of his successors, allowed the Arabian horse in America to be bred with authentic Arabian type and pure bloodlines.[77]

Arabians in America

Upon his return to America, his newly–imported horses became part of his Davenport Desert Arabian Stud in Morris Plains, New Jersey.[65] By 1908, however, the Davenport Desert Arabian Stud was listed in the Arabian Stud Book as located in Hingham, Massachusetts, and he remained closely affiliated with Bradley's Hingham Stock Farm, which became the sole owner of the horses after Davenport's death in 1912.[75] In 1908, Davenport became one of the five incorporators of the Arabian Horse Club of America (now the Arabian Horse Association).[95][96] The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) recognized the organization as the official registry for Arabian horses in 1909.[97] Prior to that time, the Thoroughbred stud books of both the United Kingdom and the United States also handled the registration of Arabian horses.[98] The reason a new organization, separate from the American Jockey Club, was needed to register Arabians came about largely because of Davenport. He had meticulously sought horses with pure bloodlines and known breeding strains with the expert assistance of Haffez,[73][99] but once out of the desert, he was not aware that he also needed to obtain written affidavits and other paperwork to document their bloodlines.[65] Additionally, because his Arabians were not shipped via Britain, they were not certified by the United Kingdom's Jockey Club before arriving in America, and without that authentication, the American Jockey Club refused to register his imported horses.[98] Another factor may have influenced the organization's stance: in a cartoon, Davenport had satirized Jockey Club President August Belmont.[100]

Haleb in particular became widely admired by American breeders, and in addition to siring Arabians, he was also crossed with Morgan and Standardbred mares.[90] In 1907, Davenport entered the stallion into the Justin Morgan Cup, a horse show competition he won, defeating 19 Morgan horses. In 1909, Haleb died[101] under mysterious circumstances. Davenport believed the horse had been poisoned.[102] He had the stallion's skull and partial skeleton prepared and sent to the Smithsonian Institution, where it became part of the museum's research collection.[101] Davenport also purchased horses from the Crabbet Park Stud in England, notably the stallion *Abu Zeyd,[lower-alpha 2] considered the best son of his famous sire, Mesaoud.[103] In 1911, Davenport described *Abu Zeyd as "the grandest specimen of the Arabian horse I have ever seen and I will give a $100 cup to the owner of any horse than can beat him."[104]

Upon Davenport's death, a significant number of his horses were obtained by W.R. Brown and his brother Herbert, where they became the foundation bloodstock for Brown's Maynesboro Stud of Berlin, New Hampshire. Included in the purchase was *Abu Zeyd.[103] The Maynesboro stud also acquired 10 mares from the Davenport estate.[105]

Personal life and other interests

Davenport married Daisy Moor of San Francisco, who traveled to Chicago while the artist was working there, and the couple wed on September 7, 1893.[28][106] They had three children:[107] Homer Clyde, born 1896; Mildred, born 1899; and Gloria Ward, born 1904.[106][lower-alpha 3] While living in a New York apartment between 1895 and 1901 not much is known of the Davenport home life except that the furnishings were luxurious.[108] By 1901, Davenport had bought both a house in East Orange, New Jersey, and a farm in Morris Plains, New Jersey. He kept many of the animals he collected and bred, including pheasants and horses, at East Orange, but decided to move both animals and himself to Morris Plains, and take the rail line dubbed the "Millionaire's Special" to work in New York.[108][109] He moved away from East Orange in 1906, though he still owned the house as late as 1909.[108] In Morris Plains, the Davenports hosted large parties attended by celebrities, artists, writers, and other influential people of the day, including Ambrose Bierce, Lillian Russell, Thomas Edison, William Jennings Bryan, Buffalo Bill Cody,[9] Frederick Remington, and the Florodora girls.[110] Instead of using a regular guestbook, Davenport would have his guests sign the clapboard siding of his home to commemorate their visits.[110]

Davenport bred various animals. "I was born with a love of horses and for all animals that do not hurt anything ... I feel happiest when I am with these birds and animals," he said, "I am a part of them without anything to explain."[111] His understanding of the dynamics of purebred animal breeding was that deviation from the original, useful type led to degeneration of a breed.[77] While best known as a horse breeder,[28] he also raised pheasants—including exotic varieties from the Himilayas—and other breeds of birds.[112] By 1905 he started a pheasant farm on his property in Morris Plains, gathering the birds he had kept on the west coast, and buying others from overseas using the profits from his first published book of cartoons.[111] As of 1908 he owned the largest private collection of pheasants and wild waterfowl in America.[106] At various times, his menagerie also contained angora goats, Persian fat-tailed sheep,[112] Sicilian donkeys, and Chinese ducks.[110] Three times, he built up collections of cockfighting roosters, once selling them to finance his start the first time he lived and worked in San Francisco.[113]

In addition to his interest in horses and birds, Davenport was also fond of dogs, notably a bull terrier named Duff, obtained as a puppy. Davenport taught Duff to do tricks and profited by loaning the dog to perform in vaudeville acts.[114] In 1908, Davenport involved himself in a controversy over the breeding of show-quality dogs, stating that he thought breeding solely for show purposes was creating an animal that was of inferior quality. He targeted certain popular breeders of purebred collies as producing animals that had less intelligence, were of poor temperament, and lacked utility. He pointedly named famous breeders whom he felt were making particularly poor decisions.[115]

The Davenport marriage did not last; Daisy did not share many of her husband's interests and intensely disliked Silverton.[116] In 1909 they separated,[117] and the parting was acrimonious.[7] Homer initially returned to New York to live,[117] but soon suffered a breakdown; he spent months recuperating in a resort hotel in San Diego, California, at the expense of his friend, sporting goods mogul Albert Spaulding.[6][67] Though he deeded his two properties over to Daisy,[7] she sued for alimony,[6] and had Homer held in contempt by a New York court for failure to pay support when he was not working. He returned to New York and obtained a new stock farm at Holmdel, New Jersey, in 1910.[7] Though his father died in 1911,[6] he began to pull his life together and returned to cartooning.[67] He met a new companion, referred to in his papers only as "Zadah",[lower-alpha 4] whom he intended to marry once his divorce case was concluded. However, he died before his scheduled August 1912 trial date.[7]

Legacy

Davenport's cartoons have had a lasting impact on the public image of Mark Hanna, both on how he was perceived at the time and on how he is remembered today.[118] Early Hanna biographer Herbert Croly, writing in 1912, the year Davenport died, deemed his subject portrayed as a "monster" by the "powerful but brutal caricatures of Homer Davenport".[119] According to Horner, the portrayal of Hanna that has stood the test of time is one that depicts him "side by side with a gigantic figure representing the trusts, and a tiny, childlike, William McKinley. He will forever be known as "Dollar Mark", thanks to Homer Davenport and many other columnists who drew him as a malevolent presence.[118] McKinley biographer Margaret Leech regretted Davenport's effect on the former president's image: "the representation of McKinley as pitiable and victimized was a poor service to his reputation. The graphic impression of his spineless subservience to Hanna would long outlive the lies of [Journal columnist] Alfred Henry Lewis."[120]

According to Davenport's biographers, Leland Huot and Alfred Powers, his Arabian horses "were to perpetuate his fame on and on into future years more than his political cartoons, so that in ten thousand stables today he is known as having been a great, great man".[28] Today, the term "CMK", meaning "Crabbet/Maynesboro/Kellogg", is a label for specific lines of "Domestic" or "American-bred" Arabian horses. It describes the descendants of horses imported to America from the desert or from Crabbet Park Stud in the late 1800s and early 1900s then bred on in the US by the Hamidie Society, Randolph Huntington, Spencer Borden, Davenport, W.R. Brown's Maynesboro Stud, W. K. Kellogg, Hearst's San Simeon Stud, and "General" J. M. Dickinson's Traveler's Rest Stud.[121]

Silverton, Oregon, gives tribute to Davenport during its annual Homer Davenport Community Festival, held annually in August. The festival began in 1980.[122]

Books

In addition to his newspaper cartoons and postcards, Davenport wrote or provided illustrations for the following books:

- Davenport, Homer C. (1898). Cartoons by Homer Davenport. New York: De Witt Publishing House. OCLC 1356802.

- Republished: Davenport, Homer C.; Gus Frederick (2006). Cartoons by Davenport – Annotated Re-Issue. Silverton, Oregon: Heron Graphics.

- Traubel, Horace l.; H. Davenport (1900). The Dollar or The Man? The Issue of the Day. Boston: Small, Maynard and Co. OCLC 2017698.

- Richardson, T.D.; Davenport, Homer (1901). Wall Street by the back door. New York: Wall Street Library Publishing Co. OCLC 973728.

- Davenport, Homer C. (1949) [1909]. My Quest of the Arabian Horse. New York: B.W. Dodge and Co. OCLC 2574660.

- Republished by The Arabian Horse Club of America, Best Publishing, Boulder, Colorado, 1949ASIN: B0007EYORE

- Davenport, Homer C. (1910). The country boy; the story of his own early life. New York: G.W. Dillingham Co. OCLC 4927261.

- Davenport, Homer; Daniel, Dan (undated). Play Ball!!!. New York: Bowne & Co. OCLC 22272087.

See also

- Theodore Thurston Geer Family history and legacy

Notes

- ↑ In 1905, Davenport was measured as being 6 feet 1 inch (1.85 m) and 190 pounds (86 kg).[1] Davenport claimed to weigh 135 pounds (61 kg) when he reached his adult height.[2]

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 An asterisk before the name of an Arabian horse indicates that the horse was imported to the United States.[3]

- ↑ Davenport dedicated Arabian Horse to Mildred[4] and Country Boy to Gloria.[5] Homer Clyde sided with his mother in the divorce.[6]

- ↑ Her full name is not known; she had a farm near New York.[7]

References

- ↑ Fowler, J.A. (May, 1905). The Phrenological Journal and Science of Health 118 (5): 140.

- ↑ Davenport, Country Boy, p. 54

- ↑ Magid, Arlene (2009). "How to Read a Pedigree". arlenemagid.com. Retrieved 2012-09-07.

- ↑ Davenport, Arabian Horse, dedication

- ↑ Davenport, Country Boy, dedication

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Curtis, Walt (2002). "Homer Davenport Oregon's Great Cartoonist". Oregon Cultural Heritage Commission. Retrieved 2013-09-23.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Huot and Powers, pp. 233–243

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Guide to the Davenport Family Papers 1848–1966". Northwest Digital Archive. Retrieved 2013-07-01.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Sass, Eileen Brorwy (June and July, 1992). "The Davenport Arabian – how they came to be.". Arabian Horse Express. Arabian Horse Express. Retrieved 2013-09-23.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 ""Homer Davenport Cartoonish".". The American Review of Reviews. The American Review of Reviews. 1912. Retrieved 2013-09-23.

- ↑ Davenport, Arabian Horse, pp. 1–2

- ↑ Davenport, Country Boy, p. 27

- ↑ Davenport, Country Boy, p. 21

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Whyte, p. 154

- ↑ Davenport, Country Boy, p. 43

- ↑ Davenport, Country Boy, p. 40

- ↑ Davenport, Arabian Horse, pp. 2–3

- ↑ Davenport, Country Boy, pp. 49–61

- ↑ Huot and Powers, pp. 9–10

- ↑ Huot and Powers, pp. 58–63

- ↑ Huot and Powers, pp. 65–66

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Whyte, p. 155

- ↑ Huot and Powers, pp. 68–70

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Huot and Powers, pp. 74–75

- ↑ Davenport, Arabian Horse, p. 4

- ↑ Davenport, Arabian Horse, p. 6

- ↑ Wells, November 1905, p. 416

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 Huot and Powers, p. 74

- ↑ Huot and Powers, pp. 76–78

- ↑ Procter, pp. 77–78

- ↑ Procter, p. 81

- ↑ Huot and Powers, pp. 87–89

- ↑ Whyte, pp. 124–125

- ↑ Whyte, pp. 149–152, 157

- ↑ Horner, pp. 99, 101

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Whyte, pp. 157–158

- ↑ Whyte, p. 157

- ↑ White, p. 158

- ↑ Procter, pp. 89–90

- ↑ Horner, p. 114

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 Whyte, p. 159

- ↑ Horner, p. 113

- ↑ Horner, p. 101

- ↑ Horner, p. 99

- ↑ Horner, p. 112

- ↑ Whyte, pp. 168–169

- ↑ Coletta, pp. 190–193

- ↑ Huot and Powers, pp. 97–99

- ↑ Huot and Powers, p. 91

- ↑ Huot and Powers, p. 92

- ↑ Horner, pp. 221–222

- ↑ Davenport, Cartoons, introduction

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 Huot and Powers, pp. 92–93, 106–107

- ↑ Huot and Powers, pp. 104–105

- ↑ Whyte, pp. 341–342

- ↑ Horner, pp. 245–252

- ↑ Huot and Powers, pp. 108–110

- ↑ Nasaw, p. 154

- ↑ Huot and Powers, p. 107

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 60.2 Huot and Powers, pp. 119–121

- ↑ Aronson, R., Sindelar, T., and Davenport, H. (1904). "Our president : march and two-step. (Musical score)". New York: : Chas. K. Harris. Retrieved 2013-09-23.

- ↑ Haskins, W. R., Taube, M. S., and Davenport, H. (1904). "He's good enough for me : march (Musical score)". New York: William R. JHaskins. Retrieved 2013-09-23.

- ↑ Huot and Powers, pp. 123, 132, 159

- ↑ Ernst, p. 46

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 65.2 65.3 Conn, p. 189

- ↑ Huot and Powers, pp. 192–194

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 67.2 Huot and Powers, pp. 234–240

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 "Homer C. Davenport, cartoonist, dies". The New York Times. May 3, 1912. Retrieved 2013-07-28.

- ↑ Huot and Powers, p. 248

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 70.2 Wells, November 1905, p. 418

- ↑ Conn, p. 188

- ↑ Conn, pp. 170, 189

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 73.2 73.3 Craver, Charles C. (August, 1972). "Homer Davenport And His Wonderful Arabian Horses". Arabian Horse News. Arabian Horse News. Retrieved 2013-09-23.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 74.2 Davenport, Arabian Horse, pp. 13–15

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 Conn, p. 191

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 76.2 Staff. "Arabian Horse History & Heritage: Introduction of Arabian Horses to North America". Arabian Horse Association. Retrieved 2013-10-13.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 77.2 Derry, p. 111

- ↑ Davenport, Arabian Horse, p. 9

- ↑ Davenport, Arabian Horse, pp. 10–12

- ↑ Davenport, Arabian Horse, p. 18

- ↑ Edwards, p. 40

- ↑ Edwards, p. 26

- ↑ Staff. "Arabian Horse History & Heritage: Horse of the Desert Bedouin". Arabian Horse Association. Retrieved 2013-10-13.

- ↑ Davenport, Arabian Horse, p. 21

- ↑ Davenport, Arabian Horse, pp. 28–30

- ↑ Davenport, Arabian Horse, pp. 35–49

- ↑ Davenport, Arabian Horse, pp. 40–41

- ↑ Davenport, Arabian Horse, pp. 48–49

- ↑ Edwards, pp. 40–41

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 Edwards, p. 43

- ↑ Davenport, Arabian Horse, p. 128

- ↑ Davenport, Arabian Horse, p. xii

- ↑ Conn, p. 187

- ↑ "About The Horses". Davenport Arabian Horse Conservancy. 2001-03-18. Retrieved 2013-10-13.

- ↑ Edwards, p. 63

- ↑ Staff (undated). "Origin of the Arabian Horse Registry of America". Arabian Horse Association. Retrieved 2013-09-23.

- ↑ Staff. "About the Arabian Horse Association – AHRA Important Dates". Arabian Horse Association. Retrieved 2013-10-13.

- ↑ 98.0 98.1 Derry, p. 112

- ↑ Edwards, p. 38

- ↑ Carver, Charles and Jeanne (2010-04-02). "The Forgotten Man: Peter Bradley's Role in Early American Breeding". Davenporthorses.org. Retrieved 2013-09-23.

- ↑ 101.0 101.1 "Encyclopedia Smithsonian: Famous Horses". Smithsonian Institution. January, 2011. Retrieved 2013-10-12.

- ↑ Sidi, Linnea (September/October 2010). "Breed Research:"X"-Rated". The Morgan Horse. Retrieved 2013-10-12.

- ↑ 103.0 103.1 Steen, Andrew S. (Summer 2012). "W.R. Brown's Maynesboro Stud". Modern Arabian Horse (Arabian Horse Association): 44–51. Retrieved 2012-08-25.

- ↑ Edwards, p. 50

- ↑ Edwards, pp. 52–53

- ↑ 106.0 106.1 106.2 Leonard, p. 600

- ↑ "Homer Davenport calls on friends". San Francisco Call. March 5, 1910. p. 11.

- ↑ 108.0 108.1 108.2 Huot and Powers, pp. 125–135

- ↑ Vogt, p. 87

- ↑ 110.0 110.1 110.2 Vogt, p. 100

- ↑ 111.0 111.1 Wells, November 1905, p. 420

- ↑ 112.0 112.1 Huot and Powers, pp. 137–140

- ↑ Huot and Powers, pp. 52–53

- ↑ Davenport, Country Boy, pp. 70–76

- ↑ Derry, pp. 63–64, 82

- ↑ Huot and Powers, pp. 74, 125

- ↑ 117.0 117.1 Huot and Powers, p. 144

- ↑ 118.0 118.1 Horner, p. 5

- ↑ Croly, p. 224

- ↑ Leech, p. 76

- ↑ Kirkman, Mary (2012). "Domestic Arabians". Arabian Horse Bloodlines. Arabian Horse Association. Retrieved 2013-11-07.

- ↑ "Homer Davenport Community Festival". Homerdavenport.com. Retrieved 2013-10-19.

Sources

- Conn, George H. (1972) [1957]. The Arabian Horse in America. New York: A. S. Barnes and Company. ISBN 978-0-498-01093-4.

- Croly, Herbert (1912). Marcus Alonzo Hanna: His Life and Work. New York: The Macmillan Company. OCLC 715683.

- Davenport, Homer C. (1898). Cartoons by Homer Davenport. New York: De Witt Publishing House. OCLC 1356802.

- Davenport, Homer C. (1949) [1909]. My Quest of the Arabian Horse. Republished by The Arabian Horse Club of America, Best Publishing Company, Boulder, Colorado. New York: B.W. Dodge and Co. OCLC 78897540.

- Davenport, Homer C. (1910). The Country Boy; the Story of His Own Early Life. New York: G.W. Dillingham Co. OCLC 4927261.

- Derry, Margaret Elsinor (2003). Bred for Perfection: Shorthorn Cattle, Collies, and Arabian Horses since 1800. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-7344-4.

- Dunn, Arthur Wallace (1922). From Harrison to Harding 1. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons.

- Edwards, Gladys Brown (1973). The Arabian: War Horse to Show Horse (Revised Collector's ed.). Covina, CA: Rich Publishing. ISBN 978-0-938276-00-5. OCLC 1148763.

- Ernst, Alice Henson (March 1965). "Homer Davenport on stage". Oregon Historical Quarterly (Portland, OR: Oregon Historical Society) 66 (1): 38–50.

- Gould, Lewis L. (1980). The Presidency of William McKinley. American Presidency. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-0206-3.

- Horner, William T. (2010). Ohio's Kingmaker: Mark Hanna, Man and Myth. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0-8214-1894-9.

- Huot, Leland; Powers, Alfred (1973). Homer Davenport of Silverton: Life of a great cartoonist. Bingen, WA: West Shore Press. ISBN 978-1-111-08852-1.

- Jones, Stanley L. (1964). The Presidential Election of 1896. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press. OCLC 445683.

- Leech, Margaret (1959). In the Days of McKinley. New York: Harper and Brothers. OCLC 456809.

- Leonard, John William (1908). Men of America: A Biographical Dictionary of Contemporaries. New York: L.R. Hamersly and Co. OCLC 5329301.

- Nasaw, David (2001). The Chief: The Life of William Randolph Hearst. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-618-15446-3.

- Procter, Ben (1998). William Randolph Hearst: The Early Years, 1863–1910. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-511277-6.

- Vogt, Virginia Dyer; Daniel B. Myers (2000). Morris Plains. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-0482-7.

- Wells, William Bittle; Lute Pease, ed. (November 1905). "The Personal Narrative of Homer Davenport: An Interview with the Famous Cartoonist, part 1". The Pacific Monthly 14 (5): 408–422.

- Wells, William Bittle; Lute Pease, ed. (December 1905). "The Personal Narrative of Homer Davenport: An Interview with the Famous Cartoonist, part 2". The Pacific Monthly 14 (6): 517–526.

- Whyte, Kenneth (2009). The Uncrowned King: The Sensational Rise of William Randolph Hearst. Berkeley, CA: Counterpoint. ISBN 978-1-58243-467-4.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Homer Davenport. |

- Hickman, Mickey (1986). Homer The Country Boy. Salem, OR: Capital City Graphics. ISBN 978-0-8323-0465-1.

- Davenport, Homer. "Prints and Photographs Online Catalogue". Library of Congress.

|