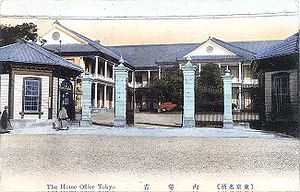

Home Ministry

The Home Ministry (内務省 Naimu-shō) was a Cabinet-level ministry established under the Meiji Constitution that managed the internal affairs of Empire of Japan from 1873-1947. Its duties included local administration, police, public works and elections.

History

early Meiji period

After the Meiji Restoration, the leaders of the new Meiji government envisioned a highly centralized state to replace the old feudal order. Within months after Emperor Meiji's Charter Oath, the ancient ritsuryō structure from the late Heian period was revived in a modified form with an express focus on the separation of legislative, administrative, and judicial functions within a new Daijō-kan system.[1]

Having just returned from the Iwakura Mission in 1873, Ōkubo Toshimichi pushed forward a plan for the creation of an “Interior ministry” within the Daijō-kan modeled after similar ministries in European nations, headed by himself. The Home Ministry was established as government department in November 1873,[2] initially as an internal security agency to deal with possible threats to the government from increasingly disgruntled ex-samurai, and political unrest spawned by the Seikanron debate. In addition to controlling the police administration, the new department was also responsible for the Family register, civil engineering, topographic surveys, censorship, and promotion of agriculture. In 1874, administration of the post office was added to its responsibilities. In 1877, overview of religious institutes was added. The head of the Home Ministry was referred to as the "Home Lord" and effectively functioned as the Head of Government.

The Home Ministry also initially had the responsibility for promoting local industry,[3] but this duty was taken over by the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce in 1881.

Under the Meiji Constitution

In 1885, with the establishment of the cabinet system, the Home Ministry was reorganized by Yamagata Aritomo, who became the first Home Minister. Bureaus were created with responsibilities for general administration, local administration, police, public works, public health, postal administration, topographic surveys, religious institutions and the national census. The administration of Hokkaidō and Karafuto Prefectures also fell under the direct jurisdiction of the Home Ministry, and all prefectural governors (who were appointed by the central government) came under the jurisdiction of the Home Ministry. In 1890, the Railroad Ministry and in 1892, the Communications Ministry were created, removing the postal administration functions from the Home Ministry.

On the other hand, with the establishment of State Shinto, a Department of Religious Affairs was added to the Home Ministry in 1900. Following the High Treason Incident, the Tokko special police force was also created in 1911. The Department of Religious Affairs was transferred to the Ministry of Education in 1913.

From the 1920s period, faced with the growing issues of agrarian unrest and Bolshvik-inspired labor unrest, the attention of the Home Ministry was increasingly focused on internal security issues. Through passage of the Peace Preservation Law#Public Security Preservation Law of 1925, the Home Ministry was able to use its security apparatus to suppress political dissent and the curtail the activities of the socialists, communists and the labor movement. The power of the Tokkō was expanded tremendously, and it expanded to include branches in every Japanese prefecture, major city, and overseas locations with a large Japanese population. In the late 1920s and 1930s, the Tokkō launched a sustained campaign to destroy the Japanese Communist Party with several waves of mass arrests of known members, sympathizers and suspected sympathizers (March 15 incident).

In 1936, an Information and Propaganda Committee was created within the Home Ministry, which issued all official press statements, and which worked together with the Publications Monitoring Department on censorship issues. In 1937, jointly with the Ministry of Education, the Home Ministry administered the National Spiritual Mobilization Movement, and the Home Ministry assisted in implementation of the National Mobilization Law in 1938 to place Japan on a total war footing. The public health functions of the Ministry were separated into the Ministry of Health in 1938.

In 1940, the Information and Propaganda Department (情報部 Jōhōbu) was elevated to the Information Bureau (情報局 Jōhōkyoku), which consolidated the previously separate information departments from the Imperial Japanese Army, Imperial Japanese Navy and Foreign Ministry under the aegis of the Home Ministry. The new Jōhōkyoku had complete control over all news, advertising and public events.[4] In February 1941 it distributed among editors a black list of writers whose articles they were advised not to print anymore.[5]

Also in 1940, with the formation of the Taisei Yokusankai political party, the Home Ministry strengthened its efforts to monitor and control political dissent, also through enforcement of the tonarigumi system, which was also used to coordinate civil defense activities through World War II. In 1942, the Ministry of Colonial Affairs was abolished, and the Home Ministry extended its influence to Japanese external territories.

Post-war Home Ministry and dissolution

After the surrender of Japan, the Home Ministry coordinated closely with the Allied occupation forces to maintain public order in occupied Japan.

One of the first actions of the post-war Home Ministry was the creation of an officially-sanctioned brothel system under the aegis of the “Recreation and Amusement Association”, which was created on August 28, 1945. The intention was officially to contain the sexual urges of the occupation forces, protect the main Japanese populace from rape and preserve the "purity" of the "Japanese race". [6] However, by October 1945, the scope of activities of the Home Ministry was increasingly limited, with the disestablishment of State Shinto and the abolishment of the Tokkō, and with censorship and monitoring of labor union activities taken under direct American supervision. Many of the employees of the Home Ministry were purged from office.

The American authorities felt that the concentration of power into a single ministry was both a cause and a symptom of Japan's pre-war totalitarian mentality, and also felt that the centralization of police authority into a massive centrally controlled ministry was dangerous for the democratic development of post-war Japan.

The Home Ministry was formally abolished on 31 December 1947, and its functions dispersed to the Ministry of Home Affairs (自治省 Jiji-shō), now the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, Ministry of Health and Welfare (厚生省 Kōsei-shō),now the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, National Public Safety Commission(国家公安委員会 Kokka-kōan-iinkai), Ministry of Construction (建設省 Kensetsu-shō), now Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport.[7]

Lords of Home Affairs

| Name | Date in office | Date out of office | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ōkubo Toshimichi | 29 November 1873 | 14 February 1874 |

| 2 | Kido Takayoshi | 14 February 1874 | 27 April 1874 |

| 3 | Ōkubo Toshimichi | 27 April 1874 | 2 August 1874 |

| 4 | Itō Hirobumi | 2 August 1874 | 28 November 1874 |

| 5 | Ōkubo Toshimichi | 28 November 1874 | 14 May 1878 |

| 6 | Itō Hirobumi | 15 May 1878 | 28 February 1880 |

| 7 | Matsukata Masayoshi | 28 February 1880 | 21 October 1881 |

| 8 | Yamada Akiyoshi | 21 October 1881 | 12 December 1883 |

| 9 | Yamagata Aritomo | 12 December 1883 | 22 December 1885 |

Ministers of Home Affairs

| Name | Cabinet | Date in office | comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yamagata Aritomo | 1st Itō | 22 December 1885 | |

| 2 | Yamagata Aritomo | Kuroda | 30 April 1888 | |

| 3 | Yamagata Aritomo | 1st Yamagata | 24 December 1889 | concurrently Prime Minister |

| 4 | Saigō Tsugumichi | 1st Yamagata | 17 May 1890 | |

| 5 | Saigō Tsugumichi | 1st Matsukata | 6 May 1891 | |

| 6 | Shinagawa Yajirō | 1st Matsukata | 1 June 1891 | |

| 7 | Soejima Taneomi | 1st Matsukata | 11 March 1892 | |

| 8 | Matsukata Masayoshi | 1st Matsukata | 8 June 1892 | concurrently Prime Minister & Finance Minister |

| 9 | Kōno Togama | 1st Matsukata | 14 July 1892 | |

| 10 | Inoue Kaoru | 2nd Itō | 8 August 1892 | |

| 11 | Nomura Yasushi | 2nd Itō | 15 October 1894 | |

| 12 | Yoshikawa Akimasa | 2nd Itō | 3 February 1896 | concurrently Justice Minister |

| 13 | Itagaki Taisuke | 2nd Itō | 14 April 1896 | |

| 14 | Itagaki Taisuke | 2nd Matsukata | 14 April 1896 | |

| 15 | Kabayama Sukenori | 2nd Matsukata | 20 September 1896 | |

| 16 | Yoshikawa Akimasa | 3rd Itō | 12 January 1898 | |

| 17 | Itagaki Taisuke | 1st Ōkuma | 30 June 1898 | |

| 18 | Saigō Tsugumichi | 2nd Yamagata | 8 November 1898 | |

| 19 | Suematsu Kenchō | 4th Itō | 19 October 1900 | |

| 20 | Utsumi Tadakatsu | 1st Katsura | 2 June 1901 | |

| 21 | Kodama Gentarō | 1st Katsura | 15 July 1903 | concurrently Minister of Education |

| 22 | Katsura Tarō | 1st Katsura | 12 October 1903 | concurrently Prime Minister |

| 23 | Yoshikawa Akimasa | 1st Katsura | 20 February 1904 | |

| 24 | Kiyoura Keigo | 1st Katsura | 16 September 1905 | concurrently Minister of Agriculture & Commerce |

| 25 | Hara Takashi | 1st Saionji | 7 January 1906 | concurrently Minister of Communications |

| 26 | Hirata Tosuke | 2nd Katsura | 14 July 1908 | |

| 27 | Hara Takashi | 2nd Saionji | 30 August 1911 | |

| 28 | Ōura Kanetake | 3rd Katsura | 21 December 1912 | |

| 29 | Hara Takashi | 1st Yamamoto | 20 February 1913 | |

| 30 | Ōkuma Shigenobu | 2nd Ōkuma | 16 April 1914 | concurrently Prime Minister |

| 31 | Ōura Kanetake | 2nd Ōkuma | 7 January 1915 | |

| 32 | Ōkuma Shigenobu | 2nd Ōkuma | 30 July 1915 | concurrently Prince Minister |

| 33 | Ichiki Kitokurō | 2nd Ōkuma | 10 August 1915 | |

| 34 | Gotō Shinpei | Terauchi | 9 October 1916 | |

| 35 | Mizuno Rentarō | Terauchi | 24 April 1918 | |

| 36 | Tokonami Takejirō | Hara | 29 September 1918 | |

| 37 | Tokonami Takejirō | Takahashi | 13 November 1921 | |

| 38 | Mizuno Rentarō | Katō Tomosaburō | 12 June 1922 | |

| 39 | Gotō Shinpei | 2nd Yamamoto | 2 September 1923 | |

| 40 | Mizuno Rentarō | Kiyoura | 7 January 1924 | |

| 41 | Wakatsuki Reijirō | Katō Takaaki | 11 June 1924 | |

| 42 | Wakatsuki Reijirō | 1st Wakatsuki | 30 January 1926 | concurrently Prime Minister |

| 43 | Osachi Hamaguchi | 1st Wakatsuki | 3 June 1926 | |

| 44 | Suzuki Kisaburō | Tanaka | 20 April 1927 | |

| 45 | Tanaka Giichi | Tanaka | 4 May 1928 | concurrently Prime Minister |

| 46 | Mochizuki Keisuke | Tanaka | 23 May 1928 | |

| 47 | Adachi Kenzō | Hamaguchi | 2 July 1929 | |

| 48 | Adachi Kenzō | 2nd Wakatsuki | 14 April 1931 | |

| 49 | Nakahashi Tokugorō | Inukai | 13 December 1931 | |

| 50 | Inukai Tsuyoshi | Inukai | 16 March 1932 | concurrently Prime Minister |

| 51 | Suzuki Kisaburō | Inukai | 25 March 1932 | |

| 52 | Yamamoto Tatsuo | Saitō | 26 May 1932 | |

| 53 | Fumio Gotō | Okada | 8 July 1934 | |

| 54 | Shigenosuke Ushio | Hirota | 9 March 1936 | concurrently Minister of Education |

| 55 | Kakichi Kawarada | Hayashi | 2 February 1937 | |

| 56 | Eiichi Baba | 1st Konoe | 4 June 1937 | |

| 57 | Nobumasa Suetsugu | 1st Konoe | 14 December 1937 | |

| 58 | Kōichi Kido | Hiranuma | 5 January 1939 | |

| 59 | Naoshi Ohara | Abe | 30 August 1939 | concurrently Minister of Health |

| 60 | Hideo Kodama | Yonai | 15 January 1940 | |

| 61 | Ejii Yasui | 2nd Konoe | 22 July 1940 | |

| 62 | Hiranuma Kiichirō | 2nd Konoe | 21 December 1940 | |

| 63 | Harumichi Tanabe | 3rd Konoe | 18 July 1941 | |

| 64 | Hideki Tōjō | Tōjō | 18 October 1941 | concurrently Prime Minister, Minister of Munitions |

| 65 | Michio Yuzawa | Tōjō | 17 February 1942 | |

| 66 | Kisaburō Andō | Tōjō | 20 April 1943 | |

| 67 | Shigeo Ōdachi | Koiso | 22 July 1944 | |

| 68 | Genki Abe | Suzuki | 7 April 1945 | |

| 69 | Iwao Yamazaki | Higashikuni | 17 August 1945 | |

| 70 | Zenjirō Horikiri | Shidehara | 9 October 1945 | |

| 71 | Chūzō Mitsuji | Shidehara | 13 January 1946 | |

| 72 | Seiichi Ōmura | 1st Yoshida | 22 April 1946 | |

| 73 | Etsujirō Uehara | 1st Yoshida | 31 January 1947 | |

| - | Tetsu Katayama | Katayama | 24 May 1947 | acting; concurrently Prime Minister |

| 74 | Kozaemon Kimura | Katayama | 1 June 1947 | office abolished 31 December 1947 |

Notes

- ↑ Ozaki, p. 10.

- ↑ Beasley, The Rise of modern Japan, pp.66

- ↑ Samuels, Rich Nation Strong Army. pp.37

- ↑ Ben-Ami Shillony, Politics and Culture in Wartime Japan, 1999, p.94

- ↑ Ben-Ami Shillony, Politics and Culture in Wartime Japan, p.95

- ↑ Herbert Bix, Hirohito and the making of modern Japan, 2001, p. 538, citing Kinkabara Samon and Takemae Eiji, Showashi : kokumin non naka no haran to gekido no hanseiki-zohoban, 1989, p.244 .

- ↑ Beasley, The Rise of modern Japan, pp.229

References

- Beasley, W.G. (2000). The Rise of Modern Japan: Political, Economic, and Social Change since 1850. Palgrave MacMillian. ISBN 0-312-23373-6.

- Samuels, Richard J (1996). Rich Nation, Strong Army:National Security and the Technological Transformation of Japan. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-312-23373-6.

- Sims, Richard (2001). Japanese Political History Since the Meiji Renovation 1868-2000. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-312-23915-7.

External links

- National Archives of Japan: Illustrations of Road to Nikko, scroll purchased by Home Ministry (1881) -- see ministry seal in red

.svg.png)