Hodge theory

In mathematics, Hodge theory, named after W. V. D. Hodge, is one aspect of the study of differential forms of a smooth manifold M. More specifically, it works out the consequences for the cohomology groups of M, with real coefficients, of the partial differential equation theory of generalised Laplacian operators associated to a Riemannian metric on M.

It was developed by Hodge in the 1930s as an extension of de Rham cohomology, and has major applications on three levels:

- Riemannian manifolds

- Kähler manifolds

- algebraic geometry of complex projective varieties, and even more broadly, motives.

In the initial development, M was taken to be a closed manifold (that is, compact and without boundary). On all three levels, the theory was very influential on subsequent work, being taken up by Kunihiko Kodaira (in Japan and later, partly under the influence of Hermann Weyl, at Princeton) and many others subsequently.

Applications and examples

De Rham cohomology

The original formulation of Hodge theory, due to W. V. D. Hodge, was for the de Rham complex. If M is a compact orientable manifold equipped with a smooth metric g, and Ωk(M) is the sheaf of smooth differential forms of degree k on M, then the de Rham complex is the sequence of differential operators

where dk denotes the exterior derivative on Ωk(M). The de Rham cohomology is then the sequence of vector spaces defined by

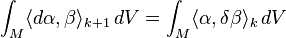

One can define the formal adjoint of the exterior derivative d, denoted δ, called codifferential, as follows. For all α ∈ Ωk(M) and β ∈ Ωk+1(M), we require that

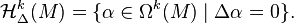

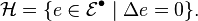

where  is the metric induced on Ωk(M). The Laplacian form is then defined by Δ = dδ + δd. This allows one to define spaces of harmonic forms

is the metric induced on Ωk(M). The Laplacian form is then defined by Δ = dδ + δd. This allows one to define spaces of harmonic forms

Since  , there is a canonical mapping

, there is a canonical mapping  . The first part of Hodge's original theorem states that φ is an isomorphism of vector spaces. In other words, for each de Rham cohomology class on M, there is a unique harmonic representative.

. The first part of Hodge's original theorem states that φ is an isomorphism of vector spaces. In other words, for each de Rham cohomology class on M, there is a unique harmonic representative.

One major consequence of this is that the de Rham cohomology groups on a compact manifold are finite-dimensional. This follows since the operators Δ are elliptic, and the kernel of an elliptic operator on a compact manifold is always a finite-dimensional vector space.

Hodge theory of elliptic complexes

In general, Hodge theory applies to any elliptic complex over a compact manifold.

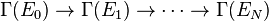

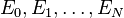

Let  be vector bundles, equipped with metrics, on a compact manifold M with a volume form dV. Suppose that

be vector bundles, equipped with metrics, on a compact manifold M with a volume form dV. Suppose that

are differential operators acting on sections of these vector bundles, and that the induced sequence

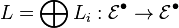

is an elliptic complex. Introduce the direct sums:

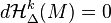

and let L* be the adjoint of L. Define the elliptic operator Δ = LL* + L*L. As in the de Rham case, this yields the vector space of harmonic sections

So let  be the orthogonal projection, and let G be the Green's operator for Δ. The Hodge theorem then asserts the following:

be the orthogonal projection, and let G be the Green's operator for Δ. The Hodge theorem then asserts the following:

- H and G are well-defined.

- Id = H + ΔG = H + GΔ

- LG = GL, L*G = GL*

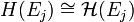

- The cohomology of the complex is canonically isomorphic to the space of harmonic sections,

, in the sense that each cohomology class has a unique harmonic representative.

, in the sense that each cohomology class has a unique harmonic representative.

Hodge structures

An abstract definition of (real) Hodge structure is now given: for a real vector space W, a Hodge structure of integer weight k on W is a direct sum decomposition of WC = W ⊗ C, the complexification of W, into graded pieces Wp, q where k = p + q, and the complex conjugation of WC interchanges this subspace with Wq, p.

The basic statement in algebraic geometry is then that the singular cohomology groups with real coefficients of a non-singular complex projective variety V carry such a Hodge structure, with  having the required decomposition into complex subspaces Hp, q. The consequence for the Betti numbers is that, taking dimensions

having the required decomposition into complex subspaces Hp, q. The consequence for the Betti numbers is that, taking dimensions

where the sum runs over all pairs p, q with p + q = k and where

The sequence of Betti numbers becomes a Hodge diamond of Hodge numbers spread out into two dimensions.

This grading comes initially from the theory of harmonic forms, that are privileged representatives in a de Rham cohomology class picked out by the Hodge Laplacian (generalising harmonic functions, which must be locally constant on compact manifolds by their maximum principle). In later work (Dolbeault) it was shown that the Hodge decomposition above can also be found by means of the sheaf cohomology groups  in which Ωp is the sheaf of holomorphic p-forms. This gives a more directly algebraic interpretation, without Laplacians, for this case.

in which Ωp is the sheaf of holomorphic p-forms. This gives a more directly algebraic interpretation, without Laplacians, for this case.

In the case of singularities or noncompact varieties, the Hodge structure has to be modified to a mixed Hodge structure, where the double-graded direct sum decomposition is replaced by a pair of filtrations. This case is much used, for example in monodromy questions.

See also

- Hodge–Arakelov theory

- Hodge cycle

- Hodge conjecture

- Period mapping

- Torelli theorem

- Variation of Hodge structure

- Mixed Hodge structure

- Logarithmic form

References

- P. Griffiths; J. Harris (1994). Principles of Algebraic Geometry. Wiley Classics Library. Wiley Interscience. p. 117. ISBN 0-471-05059-8.

- Hodge, W. V. D. (1941), The Theory and Applications of Harmonic Integrals, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-35881-1, MR 0003947

- Ofer Gabber, Lorenzo Ramero (2009). Foundations for almost ring theory.