Hick's law

Hick's law, or the Hick–Hyman Law, named after British psychologist William Edmund Hick and Ray Hyman, describes the time it takes for a person to make a decision as a result of the possible choices he or she has: increasing the number of choices will increase the decision time logarithmically. The Hick–Hyman law assesses cognitive information capacity in choice reaction experiments. The amount of time taken to process a certain amount of bits in the Hick–Hyman law is known as the rate of gain of information.

Hick's law is sometimes cited to justify menu design decisions. For example, to find a given word (e.g. the name of a command) in a randomly ordered word list (e.g. a menu), scanning of each word in the list is required, consuming linear time, so Hick's law does not apply. However, if the list is alphabetical and the user knows the name of the command, he or she may be able to use a subdividing strategy that works in logarithmic time.[1]

Background

In 1868, the relationship between having multiple stimuli and the choice reaction time was reported by Franciscus Donders. In 1885, J. Merkel discovered the response time is longer when a stimulus belongs to a larger set of stimuli. Psychologists began to see similarities between this phenomenon and the Information Theory.

Hick first began experimenting with this theory in 1951. His first experiment involved 10 lamps with corresponding Morse Code keys. The lamps would light at random every five seconds. The choice reaction time was recorded with the number of choices ranging from 2–10 lamps.

Hick performed a second experiment using the same task, while keeping the number of alternatives at 10. The participant performed the task the first two times with the instruction to perform the task as accurately as possible. For the last task, the participant was asked to perform the task as quickly as possible.

While Hick was stating that the relationship between reaction time and the number of choices was logarithmic, Hyman wanted to better understand the relationship between the reaction time and the mean number of choices. In Hyman’s experiment, he had eight different lights arranged in a 6x6 matrix. Each of these different lights was given a name, so the participant was timed in the time it took to say the name of the light after it was lit. Further experiments changed the number of each different type of light. Hyman was responsible for determining a linear relation between reaction time and the information transmitted.

Law

Given n equally probable choices, the average reaction time T required to choose among the choices is approximately:

where b is a constant that can be determined empirically by fitting a line to measured data. The logarithm expresses depth of "choice tree" hierarchy – log2 indicates binary search was performed. Addition of 1 to n takes into account the "uncertainty about whether to respond or not, as well as about which response to make."[2]

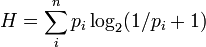

In the case of choices with unequal probabilities, the law can be generalized as:

where H is the information-theoretic entropy of the decision, defined as:

where pi refers to the probability of the ith alternative yielding the information-theoretic entropy.

Hick's law is similar in form to Fitts's law. Hick's law has a logarithmic form because people subdivide the total collection of choices into categories, eliminating about half of the remaining choices at each step, rather than considering each and every choice one-by-one, which would require linear time.

Relation to IQ

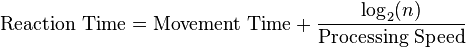

"Bit" is the unit of log2(n)

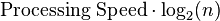

E. Roth (1964) demonstrated a correlation between IQ and information processing speed, which is the reciprocal of the slope of the function:[3]

where n is the number of choices. The time it takes to come to a decision is:

Stimulus–response compatibility

The stimulus–response compatibility is known to also affect the choice reaction time for the Hick–Hyman Law. This means that the response should be similar to the stimulus itself (such as turning a steering wheel to turn the wheels of the car). The action the user performs is similar to the response the driver receives from the car.

See also

- Power Law of Practice

Notes

- ↑ Landauer, T. K.; Nachbar, D. W. (1985). "Selection from alphabetic and numeric menu trees using a touch screen". Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems - CHI '85. p. 73. doi:10.1145/317456.317470. ISBN 0897911490.

- ↑ Card, Stuart K.; Moran, Thomas P.; Newell, A. (1983). The Psychology of Human–Computer Interaction. Hilldale, London: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- ↑ (German) Roth, E. (1964). "Die Geschwindigkeit der Verarbeitung von Information und ihr Zusammenhang mit Intelligenz". Zeitschrift fuer experimentelle und angewandte Psychologie 11: 616–622.

References

- Cockburn, Andy; Gutwin, Carl; Greenberg, Saul (April 28–May 3, 2007). "A predictive model of menu performance". Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems (San Jose, California). doi:10.1.1.183.7520.

- Hick, W. E. (1 March 1952). "On the rate of gain of information". Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 4 (1): 11–26. doi:10.1080/17470215208416600.

- Hyman, R (March 1953). "Stimulus information as a determinant of reaction time". Journal of Experimental Psychology 45 (3): 188–96. PMID 13052851.</ref>

- Roy, Q.; Malacria, S.; Lecolinet, E.; Guiard, Y.; Eagan, J. (April 27–May 2, 2013). "Augmented Letters: Mnemonic Gesture-Based Shortcuts". Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems (Paris, France). doi:10.1145/2470654.2481321.

- Seow, Steven C. (2005). "Information Theoretic Models of HCI: A Comparison of the Hick–Hyman Law and Fitts' Law". Human–Computer Interaction' 20 (3): 315–352. doi:10.1.1.86.4509.

- Welford, Alan T. (1968). Fundamentals of Skill. Methuen, Massachusetts. pp. 61–65.