Hexachlorophene

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

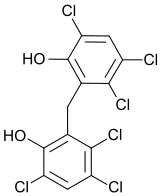

| 2,2'-methylenebis(3,4,6-trichlorophenol) | |

| Clinical data | |

| Trade names | Phisohex |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | monograph |

| Legal status | ? |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 70-30-4 |

| ATC code | D08AE01 QP52AG02 |

| PubChem | CID 3598 |

| DrugBank | DB00756 |

| ChemSpider | 3472 |

| UNII | IWW5FV6NK2 |

| KEGG | D00859 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL496 |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C13H6Cl6O2 |

| Mol. mass | 406.902 g/mol |

| SMILES

| |

| |

| Physical data | |

| Melt. point | 164 °C (327 °F) |

| | |

Hexachlorophene, also known as Nabac, is a disinfectant. The compound occurs as a white to light-tan crystalline powder, which either is odorless or produces a slightly phenolic odor. In medicine, hexachlorophene is very useful as a topical anti-infective, anti-bacterial agent, often used in soaps and toothpaste. It is also used in agriculture as a soil fungicide, plant bactericide, and acaricide.

Hexachlorophene products can be lethal from percutaneous (through the skin) absorption. Children may be specifically susceptible. Hexachlorophene (6.3%) was added to “baby powder” in France due to a manufacturing error. It, or possibly contaminating dioxins, caused encephalopathy and ulcerative skin lesions. 36 of 204 exposed children died within a few days of exposure.[1]

Two companies manufactured over-the-counter preparations. One, by The Mennen Company, Morristown, NJ, was Baby Magic Bath. Mennen recalled the product, and it was removed from retail distribution. Right after the withdrawal, there was an outbreak of Staphylococcus infections in hospitals across the USA.[2]

A commercial preparation of the drug, pHisoHex, was widely used as an effective antibacterial skin cleanser in the treatment of acne. In the US during the 1960s, it was available over the counter, and remains available as a prescription body wash. In the E.U. during the 1970s and 1980s, it was available over the counter. A related product, pHisoAc, was used as a skin mask to dry and peel away acne lesions. Another preparation, pHiso-Scrub, was a hexachlorophene-impregnated sponge for scrubbing; it has since been discontinued.

In 1969, hexachlorophene became suspected of causing cancer, and studies determined that oral ingestion of hexachlorophene led to weakness and paralysis in laboratory rats.[3] In 1972 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration outlawed its use in non-medicinal products like Dial soap.[4] In 1973, after studies found relatively high concentrations of hexachlorophene in the blood of neonates washed with a 3% solution it was withdrawn from over-the-counter sales, though still available by prescription.[3] A 1978 study undertaken by the U.S. National Institutes of Health[5] indicated that hexachlorophene does not cause cancer. However, the MSDS still lists this compound as an experimental teratogen. Possibly because of the previous questions concerning its effects, most dermatologists today do not prescribe it for acne treatment.

Several substitute products (including triclosan) were developed, but none had the germ-killing capability of hexachlorophene.

Trade names

Trade names for hexachlorophene include: Acigena, Almederm, AT7, AT17, Bilevon, Exofene, Fostril, Gamophen, G-11, Germa-Medica, Hexosan, Septisol, Surofene.[6]

References

- ↑ "Proceedings of the International Conference on Occupational & Environmental Exposures of Skin to Chemicals: Science & Policy". CDC. Retrieved November 17, 2009.

- ↑ Dixon, RE; Kaslow, RA; Mallison, GF; Bennett, JV (1973). "Staphylococcal disease outbreaks in hospital nurseries in the United States--December 1971 through March 1972". Pediatrics 51 (2): 413–7. PMID 4700144.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Evaluation of Drug Safety and Efficacy. Hexachlorophene: Case in Point: The Saga of Hexachlorophene". NIH. Retrieved September 21, 2010.(subscription required)

- ↑ "US order curbs hexachlorophene", Milwaukee Sentinel, September 23, 1972

- ↑ "BIOASSAY OF HEXACHLOROPHENE FOR POSSIBLE CARCINOGENICITY". NIH. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ↑ "Hexachlorophene". PharmGKB. Retrieved 2012-012-28.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||