Hester Chapone

Hester Chapone, née Mulso (1727–1801), writer of conduct books for women, was born on 27 October 1727 at Twywell, Northamptonshire,

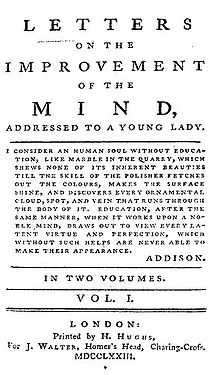

The daughter of Thomas Mulso (1695–1763), a gentleman farmer, and his wife (d. 1747/8), a daughter of Colonel Thomas, Hester wrote a romance at the age of nine, 'The Loves of Amoret and Melissa', which earned her mother's disapproval. She was educated more thoroughly than most girls in that period, learning French, Italian and Latin, and began writing regularly and corresponding with other writers at the age of 18. Her earliest published works were four brief pieces of Samuel Johnson's journal The Rambler in 1750.[1] She was married in 1760 to the solicitor John Chapone (c.1728–1761), who was the son of an earlier moral writer, Sarah Chapone (1699-1764), but soon widowed. Hester Chapone was associated with the learned ladies or Bluestockings who gathered around Elizabeth Montagu, and was the author of Letters on the Improvement of the Mind and Miscellanies.

Conduct books

The former was first written for her 15-year-old niece, in 1773, but by 1800 it had been through at least 16 editions. A further 12 editions appeared until 1829, at least one of them a French translation. They focused on encouraging rational understanding through the reading of the Bible, history and literature. The girl was also supposed to study book-keeping, household management and botany, geology, astronomy. Only sentimental novels were to be avoided. Mary Wollstonecraft singled it out as one of the few examples of the self-improvement genre deserving of praise.

This tide of advice or conduct books reached its height between 1760 and 1820 in Britain; one scholar refers to the period as "the age of courtesy books for women".[2] As Nancy Armstrong writes in her seminal work on this genre, Desire and Domestic Fiction (1987): "so popular did these books become that by the second half of the eighteenth century virtually everyone knew the ideal of womanhood they proposed".[3] Chapone's is a typical example.[4]

Conduct books integrated the styles and rhetorics of earlier genres, such as devotional writings, marriage manuals, recipe books, and works on household economy. They offered their readers a description of (most often) the ideal woman while at the same time handing out practical advice. Thus, not only did they dictate morality, but they also guided readers' choice of dress and outlined "proper" etiquette.[5] Chapone's work, in particular, appealed to Wollstonecraft at this time and influenced her composition of Thoughts because it argued "for a sustained programme of study for women" and was based on the idea that Christianity should be "the chief instructor of our rational faculties".[6] Moreover, it emphasized that women should be considered rational beings and not left to wallow in sensualism.[7] When Wollstonecraft wrote A Vindication of the Rights of Woman in 1792, she drew on both Chapone and Macaulay's works.[8] Another admirer, and also a personal friend, was the novelist and diarist Frances Burney. Their surviving correspondence includes a letter of condolence of 4 April 1799, from Burney to Chapone, on the death in childbirth of Jane Jeffreyes, née Mulso, the niece to whom the Letters on the Improvement of the Mind had been addressed.[9]

Cultural influence

Elizabeth Gaskell, the nineteenth century novelist, refers to Chapone as an epistolatory model, bracketing her in Cranford with Elizabeth Carter, a much better educated Bluestocking.[10]

Notes

- ↑ ODNB entries for Hester Chapone and Sarah Chapone , retrieved 3 August 2011. Subscription required.

- ↑ Qtd. in Armstrong, 61.

- ↑ Armstrong, 61.

- ↑ Sutherland, 28; 35.

- ↑ Sutherland, 26.

- ↑ Sutherland, 29.

- ↑ Sutherland, 41.

- ↑ Sutherland, 42–43.

- ↑ The Journals and Letters of Fanny Burney (Madame D'Arblay). Volume 4, 1797-1801. Edited by Joyce Hemlow, et al. (London: Oxford University Press, 1973). p. 271.

- ↑ Cranford, CHAPTER V--OLD LETTERS

Bibliography

- Armstrong, Nancy. Desire and Domestic Fiction: A Political History of the Novel. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987. ISBN 0-19-506160-8.

- Elizabeth Eger and Lucy Peltz. Brilliant Women: 18th-Century Bluestockings, National Portrait Gallery, London, 2008.

- Sutherland, Kathryn. "Writings on Education and Conduct: Arguments for Female Improvement". Women and Literature in Britain 1700–1800. Ed. Vivien Jones. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-521-58680-1.

- Barbara Eaton: Yes papa! : Mrs Chapone and the bluestocking circle; a biography of Hester Mulso - Mrs Chapone (1727 - 1801), a bluestocking, London : Francis Boutle Publishers, 2012, ISBN 978-1-903427-70-5

- Biography in Dictionary of National Biography

External links

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Hester Chapone |

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Cousin, John William (1910). A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. London: J. M. Dent & Sons. Wikisource

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Cousin, John William (1910). A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature. London: J. M. Dent & Sons. Wikisource

|