Herman Melville

| Herman Melville | |

|---|---|

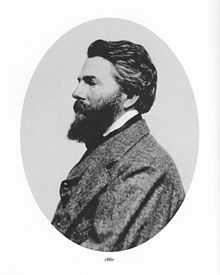

Herman Melville, 1870. Oil painting by Joseph Eaton. | |

| Born |

August 1, 1819 New York City, New York, US |

| Died |

September 28, 1891 (aged 72) New York City, New York, US |

| Occupation | Novelist, short story writer, teacher, sailor, lecturer, poet, customs inspector |

| Nationality | American |

| Genres | Travelogue, Captivity narrative, Sea story, Gothic Romanticism, Allegory, Tall tale |

| Literary movement | Romanticism and Skepticism |

|

| |

| Signature |

|

Herman Melville (August 1, 1819 – September 28, 1891) was an American writer of novels, short stories and poetry. His contributions to the Western canon are the whaling novel Moby-Dick (1851); the short work Bartleby, the Scrivener (1853) about a clerk in a Wall Street office; the slave ship narrative Benito Cereno (1855); and Billy Budd, Sailor, left unfinished at his death and published in 1924.

Around his twentieth year he was a schoolteacher for a short time, then became a seaman when his father met business reversals. On his first voyage he jumped ship in the Marquesas islands, where he lived for a time. His first book, an account of that time, Typee, became a bestseller and Melville became known as the "man who lived among the cannibals." After literary success in the late 1840s, the public indifference to Moby-Dick (1851) put an end to his career as a popular author. During his later decades, Melville worked at the New York Customs House and published volumes of poetry which are now esteemed but were not read in his lifetime.

When he died in 1891, Melville was almost completely forgotten. It was not until the "Melville Revival" in the early 20th century that his work won recognition, especially Moby-Dick, which was hailed as one of the literary masterpieces of both American and world literature. He was the first writer to have his works collected and published by the Library of America.

Biography

Birth and Ancestry

Born Herman Melvill [lower-alpha 1] in New York City on August 1, 1819, to Allan Melvill (1782-1832)[2] and Maria Gansevoort Melvill (1791-1872), Herman was the third of eight children born between 1815 and 1830. His siblings were Gansevoort (1815-1846), Helen Maria (1817-1888), Augusta (1821-1876), Allan (1823-1872), Catherine (1825-1905), Frances Priscilla (1827-1885), and Thomas (1830-1884), who eventually became a governor of Sailors Snug Harbor. Part of a well-established and colorful Boston family, Melville's father, Allan, spent a good deal of time abroad as a commission merchant and an importer of French dry goods, specializing in what would now be called accessories. An advertisement he placed in 1824 in a New York newspaper[lower-alpha 2] mentions, among other things, fancy scarfs, elastic and silk garters, artificial flowers, cravat stiffners, rich satin striped and figured blk Silk Vestings, gros de naples, belt and watch ribbons, horse skin gloves, cologne and lavender waters.[3]

Melville's paternal grandfather, Major Thomas Melvill (1751-1832), was a veteran of the American Revolutionary War who "proudly showed his grandson the vial containg tea leaves brushed from his clothes after he had taken part in the Boston Tea Party, dressed in Indian garb and warpaint."[4] Thomas Melvill, who refused to change the style of his clothing or manners to fit the times, was depicted in Oliver Wendell Holmes's poem "The Last Leaf." Herman Melville visited his grandfather in Boston frequently, and Allan Melvill, also frequently, turned to Thomas Melvill in times of financial need.

The maternal side of Melville's family had been among Dutch settlers of the Hudson Valley in present-day New York state. His maternal grandfather General Peter Gansevoort (1749-1812) was famous for having commanded the defense of Fort Stanwix in 1777, and for his "valor in the face of superior numbers of enemy troops";[5] in his gold-laced uniform, the general sat for a portrait painted by Gilbert Stuart, which is described in Melville's 1852 novel, Pierre. Melville drew upon his familial as well as his nautical background. Like the titular character in Pierre, Melville found satisfaction in his "double revolutionary descent."[6]

Allan Melvill subscribed to his own father's Unitarianism: which doctrines, according to the more pious members of the family, including Maria Gansevoort Melvill, his wife and Herman's mother, tended to diminish God's majesty in favor of the dignity of man. In contrast, Maria Gansevoort Melvill was committed to the Dutch Reformed version of the Calvinist creed that had ruled in her family. The severe Protestantism of the Gansevoort's tradition ensured that she knew her Bible well, in English as well as Dutch,[lower-alpha 3] the language she had grown up speaking with her parents. Maria made certain that her children were familiar with biblical stories, exempla, and precedents. For Herman Melville "characters from the Bible always remained as vividly alive as the worthies and villains of his own time."[7]

1824-1839: Early years and education

Melville's education began when he was five years old. In 1826 Melville contracted scarlet fever, permanently weakening his eyesight.[8] Allan Melvill, who sent both Gansevoort and Herman to the New York Male High School, described Melville in 1826 as "very backwards in speech & somewhat slow in comprehension".[9] At eight years old, in February 1828, Melville won a prize as 'best Speaker in the introductory Department.'[10] A 1828 letter to his aunt Lucy (1795-1877), the second youngest of his father's five sisters, is Melville's earliest surviving writing:

My dear Aunt, You asked me to write you a letter but I thought that I could not write well enough before this. I now study Spelling, Arithmetic, Grammar, Geography, Reading, and Writing. I past a very pleasant vacation at Bristol. give my love to Grandmamma, Grandpapa, and all my aunts. Your dear Nephew, Herman Melvill.[11]

In October 1828 Melville's mother and his two youngest sisters paid a visit to Catherine Van Schaick Gansevoort (1751-1830), his maternal grandmother and General Gansevoort's widow. On that occasion, Melville wrote a letter to his grandmother in which he gave a fuller account of his school curriculum. This letter, dated 11 October, and the previous one are his sole surviving writings prior to 1837:

Dear grandmother, This is the third letter that I ever wrote so you must not think it will be very good. I now study Geography, Gramar, Arithmetic, Writing, Speaking, Spelling, and read in the Scientific class book. I enclose in this letter a drawing for my dear Grandmother. Give my love to Grandmamma Uncle Peter, and Aunt Mary. And my sisters. Your affectionate Grandson, Herman Melvill.[12]

The letter suggests that Melville followed the standard elementary curriculum of the day. In 1829 both Gansevoort and Herman were transferred to Columbia Grammar & Preparatory School, with Herman enrolling in the English Department on 28 September.[13]

Overextended financially and emotionally unstable, the senior Melville tried to recover from his setbacks by moving his family to Albany in 1830 and going into the fur business.[14] In Albany, Melville attended the Albany Academy from October 1830 to October 1831, where he took the standard preparatory course, studying reading and spelling; penmanship; arithmetic; English grammar; geography; natural history; universal, Grecian, Roman and English history; classical biography; and Jewish antiquities.[15] It is unknown why he left the Academy in October 1831, three months before his father's death. His brothers Gansevoort and Allan continued their attendance. "The ubiquitous classical references in Melville's published writings," as Melville scholar Merton Sealts observed, "suggest that his study of ancient history, biography, and literature during his school days left a lasting impression on both his thought and his art, as did his almost encyclopedic knowledge of both the Old and the New Testaments."[16]

The father's new venture was unsuccessful; he was forced to declare bankruptcy and died soon afterward, when Herman was 12. His family was left penniless.[14] Although Maria had expected some inheritance when her mother died, her kin were apparently more concerned with protecting their own interests than hers.

In 1832 Melville worked in Albany as a bank clerk and spent a year in Pittsfield with Thomas Melvill, his uncle. He returned to Albany Academy for two quarters, from October 1836 to March 1837, where he studied the classics. He may have enrolled in order to prepare for his new career in school teaching which he embarked upon in Pittsfield in the fall of 1837.[17] In 1838 he quit teaching and enrolled in the local academy at Lansingburgh, New York, where his mother now lived. He studied engineering and surveying, perhaps to qualify for work on the Erie Canal, though he never did such work.[18] This was the last formal education Melville received.

1839-1844: Years at sea

In June 1839 Melville signed aboard the merchant ship St. Lawrence as a "boy"[19] (a green hand) for a cruise from New York to Liverpool. He returned on the same ship on the first of October, after five weeks in England. Redburn: His First Voyage (1849) is partly based on his experiences of this journey. Melville resumed teaching, now at Greenbush, New York, but left after one term. In the summer of 1840 his trip to Galena took place.[18]

From 1838 to 1847 he resided at what is now known as the Herman Melville House in Lansingburgh, New York.[20] In late 1840 he decided to sign up for more work at sea.

On January 3, 1841, he sailed from Fairhaven, Massachusetts, on the whaler Acushnet,[21] which was bound for the Pacific Ocean. He was later to comment that his life began that day. The vessel sailed around Cape Horn and traveled to the South Pacific. Melville left little direct accounts of the events of this 18-month voyage, although his whaling romance, Moby-Dick; or, The Whale, probably describes many aspects of life on board the Acushnet. Melville deserted the Acushnet in the Marquesas Islands in July 1842.[22]

For three weeks he lived among the Typee natives, who were called cannibals by the two other tribal groups on the island—though they treated Melville very well. Typee, Melville's first book, describes a brief love affair with a beautiful native girl, Fayaway, who generally "wore the garb of Eden" and came to epitomize the guileless noble savage in the popular imagination.

Melville did not seem to be concerned about the consequences of leaving the Acushnet. He boarded an Australian whale ship, the Lucy Ann, bound for Tahiti; took part in a mutiny and was briefly jailed in the native Calabooza Beretanee. After release, he spent several months as beachcomber and island rover ('omoo' in Tahitian), eventually crossing over to Moorea. He signed articles on yet another whaler for a six-month cruise (November 1842 − April 1843), which terminated in Honolulu. After working as a clerk for four months, he joined the crew of the frigate USS United States, which reached Boston in October 1844. He drew from these experiences in his books Typee, Omoo, and White-Jacket.

Melville completed Typee in the summer of 1845, while living in Troy, New York. After some difficulty in arranging publication,[23] he saw it first published in 1846 in London, where it became an overnight bestseller. The Boston publisher subsequently accepted Omoo sight unseen. Typee and Omoo gave Melville overnight renown as a writer and adventurer, and he often entertained by telling stories to his admirers. As the writer and editor Nathaniel Parker Willis wrote, "With his cigar and his Spanish eyes, he talks Typee and Omoo, just as you find the flow of his delightful mind on paper".[23] These did not generate enough royalties to support him financially, however.

Marriage

On August 4, 1847, Melville married Elizabeth Shaw, daughter of Lemuel Shaw, the Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court. The couple honeymooned in Canada and then moved into a house on Fourth avenue in New York City. In 1850, the couple moved to Massachusetts. They had four children: two sons and two daughters.

Moby-Dick and later works

During these city years, Melville wrote most of Mardi, completed Redburn and White-Jacket, and began the first chapters of Moby-Dick.[24] He had no problems in finding publishers for Redburn and White-Jacket; however, the longer, allegorical Mardi proved a disappointment for readers who wanted another rollicking and exotic sea yarn.

At first Moby-Dick moved swiftly. In early May 1850 he wrote to Richard Henry Dana, also a sea author, saying he was already "half way" done. In June he described the book to his English publisher as "a romance of adventure, founded upon certain wild legends in the Southern Sperm Whale Fisheries," and promised it would be done by the fall. Since the manuscript for the book has not survived, it is impossible to know for sure its state at this critical juncture. A consensus among critics is that at this point, the book was a sea yarn along the lines of his earlier work. Over the next several months, Melville's plan for the book underwent a radical transformation into what has been described as "the most ambitious book ever conceived by an American writer."[25]

In September 1850 the Melvilles purchased Arrowhead, a farm house in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. (It is now preserved as a house museum and has been designated a National Historic Landmark.) Here Melville and Elizabeth lived for 13 years. While living at Arrowhead, Melville befriended the author Nathaniel Hawthorne, who lived in nearby Lenox. Melville wrote ten letters to Hawthorne, "all of them effusive, profound, deeply affectionate."[26] Melville was inspired and encouraged by his new relationship with Hawthorne[27] during the period that he was writing Moby-Dick. He dedicated this new novel to Hawthorne, though their friendship was to wane only a short time later.[28]

Pierre: or, The Ambiguities, a novel partly autobiographical and difficult in tone, was not well received. The New York Day Book on September 8, 1852, published a venomous attack headlined "HERMAN MELVILLE CRAZY." The item, offered as a news story, reported,

A critical friend, who read Melville's last book, Ambiguities, between two steamboat accidents, told us that it appeared to be composed of the ravings and reveries of a madman. We were somewhat startled at the remark, but still more at learning, a few days after, that Melville was really supposed to be deranged, and that his friends were taking measures to place him under treatment. We hope one of the earliest precautions will be to keep him stringently secluded from pen and ink."[29]

Following this and other scathing reviews of Pierre, publishers became wary of Melville's work. His publisher, Harper & Brothers, rejected his next manuscript, presumed to be Isle of the Cross, which has been lost. The strain of these reversals weighed on Melville. In late 1856 he made a six-month Grand Tour of the British Isles and the Mediterranean. While in England, he spent three days with Hawthorne, who had taken an embassy position there. At the seaside village of Southport, amid the sand dunes where they had stopped to smoke cigars, they had a conversation which Hawthorne later described in his journal:

Melville, as he always does, began to reason of Providence and futurity, and of everything that lies beyond human ken, and informed me that he 'pretty much made up his mind to be annihilated'; but still he does not seem to rest in that anticipation; and, I think, will never rest until he gets hold of a definite belief. It is strange how he persists—and has persisted ever since I knew him, and probably long before—in wandering to-and-fro over these deserts, as dismal and monotonous as the sand hills amid which we were sitting. He can neither believe, nor be comfortable in his unbelief; and he is too honest and courageous not to try to do one or the other. If he were a religious man, he would be one of the most truly religious and reverential; he has a very high and noble nature, and better worth immortality than most of us.[30]

Melville's subsequent visit to the Holy Land inspired his epic poem Clarel.[31][32]

On April 1, 1857, Melville published his last full-length novel, The Confidence-Man. This novel, subtitled His Masquerade, has won general acclaim in modern times as a complex and mysterious exploration of issues of fraud and honesty, identity and masquerade. But, when it was published, it received reviews ranging from the bewildered to the denunciatory.[33]

Later years

To repair his faltering finances, Melville was advised by friends to enter what was, for others, the lucrative field of lecturing. From 1857 to 1860, he spoke at lyceums, chiefly on Roman statuary and sightseeing in Rome.[34] Turning to poetry, he gathered a collection of verse, but it failed to interest a publisher.

In 1863 he and his wife resettled in New York City with their four children. After the end of the American Civil War, he published Battle Pieces and Aspects of the War (1866), a collection of over 70 poems that was generally ignored by the critics. A few gave him patronizingly favorable reviews. In 1866 Melville's wife and her relatives used their influence to obtain a position for him as customs inspector for the City of New York (a humble but adequately paying appointment). He held the post for 19 years. In a notoriously corrupt institution, Melville soon won the reputation of being the only honest employee of the customs house.[35] But from 1866, his professional writing career can be said to have come to an end.

Melville spent years writing a 16,000-line epic poem, Clarel, inspired by his 1856 trip to the Holy Land.[31][36] His uncle, Peter Gansevoort, by a bequest, paid for the publication of the massive epic in 1876. But the run failed miserably in sales, and the unsold copies were burned when Melville was unable to afford to buy them at cost.

As his professional fortunes waned, Melville had difficulties at home. Elizabeth's relatives repeatedly urged her to leave him under the belief that he may have been insane, but she refused. In 1867 his oldest son, Malcolm, shot himself, perhaps accidentally.

While Melville had his steady customs job, his wife managed to wean him off alcohol. He no longer showed signs of agitation or insanity. But depression recurred after the death of his second son, Stanwix, in San Francisco early in 1886. Melville retired in 1886, after several of his wife's relatives died and left the couple legacies which Mrs. Melville administered with skill and good fortune.

As English readers, pursuing the vogue for sea stories represented by such writers as G. A. Henty, rediscovered Melville's novels in the late nineteenth century, the author had a modest revival of popularity in England, though not in the United States. He wrote a series of poems, with prose head notes, inspired by his early experiences at sea. He published them in two collections, each issued in a tiny edition of 25 copies for his relatives and friends: John Marr (1888) and Timoleon (1891).

Intrigued by one of these poems, he began to rework the headnote, expanding it first as a short story and eventually as a novella. He worked on it on and off for several years, but when he died in September 1891, the piece was unfinished. His widow Elizabeth added notes and edited it, but the manuscript was not discovered until 1919, by Raymond Weaver, his first biographer. He worked at transcribing and editing a full text, which he published in 1924 as Billy Budd, Sailor. It was an immediate critical success in England and soon one in the United States. The authoritative version was published in 1962, after two scholars studied the papers for several years.

Death

Melville died at his home in New York City early on the morning of September 28, 1891, at age 72. The doctor listed "cardiac dilation" on the death certificate.[37] He was interred in the Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, New York. A common story recounts that his New York Times obituary called him "Henry Melville", implying that he was unknown and unappreciated at his time of death, but the story is not true. A later article was published on October 6 in the same paper, referring to him as "the late Hiram Melville", but this appears to have been a typesetting error.[38]

Critical response

Contemporary criticism

Melville was not financially successful as a writer, having earned just over $10,000 for his writing during his lifetime.[39] After his success with travelogues based on voyages to the South Seas and stories based on misadventures in the merchant marine and navy, Melville's popularity declined dramatically. By 1876, all of his books were out of print.[40] In the later years of his life and during the years after his death, he was recognized, if at all, as a minor figure in American literature.

Melville revival and Melville studies

A confluence of publishing events in the 1920s, now commonly called "the Melville Revival", brought about a reassessment of his work. The two books generally considered most important to the Revival were Raymond Weaver's 1921 biography Herman Melville: Man, Mariner and Mystic and his 1924 edition of Melville's last manuscript, Billy Budd, which he discovered unfinished among papers given to him by Melville's granddaughter. The other works that helped fan the Revival flames were Carl Van Doren's The American Novel (1921), D. H. Lawrence's Studies in Classic American Literature (1923), Carl Van Vechten's essay in The Double Dealer (1922), and Lewis Mumford's biography, Herman Melville: A Study of His Life and Vision (1929).[41]

Starting in the mid 1930s, the Yale University scholar Stanley T. Williams supervised more than a dozen dissertations on Melville which were published as books. His students were prominent in establishing Melville Studies as an academic field concerned with texts and manuscripts, tracing Melville's influences and borrowings, and exploiting archives and local publications.[42] Jay Leyda, better known for his work in film, spent more than a decade gathering documents and records for the day by day Melville Log (1951). In the same year Newton Arvin published the critical biography, Herman Melville, which won the nonfiction National Book Award.

That year, the novella Billy Budd was adapted as an award-winning play on Broadway, and premiered as an opera by Benjamin Britten, with a libretto on which the author E.M. Forster collaborated. In 1962 Peter Ustinov wrote, directed and produced a film based on the stage version, starring the young Terence Stamp and for which he took the role of Captain Vere. All these works brought more attention to Melville.

In the 1960s, Northwestern University Press, in alliance with the Newberry Library and the Modern Language Association, launched a project to edit and published reliable critical texts of Melville's complete works, including unpublished poems, journals, and correspondence. The aim of the editors was to present a text "as close as possible to the author's intention as surviving evidence permits." The volumes have extensive appendices, including textual variants from each of the editions published in Melville's lifetime, an historical note on the publishing history and critical reception, and related documents. In many cases, it was not possible to establish a "definitive text," but the edition supplies all evidence available at the time. Since the texts were prepared with financial support from the United States Department of Education, no royalties are charged, and they have been widely reprinted.

The Melville Society

In 1945, The Melville Society was founded, a non-profit organisation dedicated to the study of Melville's life and works. Between 1969 and 2003 it published 125 issues of Melville Society Extracts, which are now freely available on the society's website. Since 1999 it publishes Leviathan: A Journal of Melville Studies, currently three issues a year, published by Johns Hopkins university Press.

Melville's poetry

Melville did not publish poetry until late in life and his reputation as a poet was not high until late in the 20th century. After the Civil War, he published Battle Pieces and Aspects of the War, which did not sell well; of the Harper & Bros. printing of 1200 copies, only 525 had been sold ten years later.[43] Tending to outrun the tastes of his readers, Melville's epic-length verse-narrative Clarel, about a student's pilgrimage to the Holy Land, was also quite obscure, even in his own time. Among the longest single poems in American literature, Clarel, published in 1876, had an initial printing of 350 copies. The critic Lewis Mumford found a copy of the poem in the New York Public Library in 1925 "with its pages uncut"—in other words, it had sat there unread for 50 years.[44]

Melville, says recent literary critic Lawrence Buell, “is justly said to be nineteenth-century America’s leading poet after Whitman and Dickinson, yet his poetry remains largely unread even by many Melvillians.” True, Buell concedes, even more than most Victorian poets, Melville turned to poetry as an “instrument of meditation rather than for the sake of melody or linguistic play.” It is also true that he turned from fiction to poetry late in life. Yet he wrote twice as much poetry as Dickinson and probably as many lines as Whitman, and he wrote distinguished poetry for a quarter of a century, twice as long as his career publishing prose narratives. The three novels of the 1850s which Melville worked on most seriously to present his philosophical explorations, Moby-Dick, Pierre, and The Confidence Man, seem to make the step to philosophical poetry a natural one rather than simply a consequence of commercial failure. [45]

In 2000 the Melville scholar Elizabeth Renker wrote "a sea change in the reception of the poems is incipient."[46] Some critics now place him as the first modernist poet in the United States; others assert that his work more strongly suggests what today would be a postmodern view.[47] Henry Chapin wrote in an introduction to John Marr and Other Poems, a collection of Melville's poetry, "Melville's loveable freshness of personality is everywhere in evidence, in the voice of a true poet".[48] The poet and novelist Robert Penn Warren was a leading champion of Melville as a great American poet. Warren issued a selection of Melville's poetry prefaced by an admiring critical essay. The poetry critic Helen Vendler remarked of Clarel : "What it cost Melville to write this poem makes us pause, reading it. Alone, it is enough to win him, as a poet, what he called 'the belated funeral flower of fame'".[49]

Gender studies revisionism

Although not the primary focus of Melville scholarship, there has been an emerging interest in the role of gender and sexuality in some of his writings.[50][51][52] Some critics, particularly those interested in gender studies, have explored the male-dominant social structures in Melville's fiction.[53] For example, Alvin Sandberg claimed that the short story "The Paradise of Bachelors and the Tartarus of Maids" offers "an exploration of impotency, a portrayal of a man retreating to an all-male childhood to avoid confrontation with sexual manhood," from which the narrator engages in "congenial" digressions in heterogeneity.[54] In line with this view, Warren Rosenberg argues the homosocial "Paradise of Bachelors" is shown to be "superficial and sterile."[52]

David Harley Serlin observes in the second half of Melville's diptych, "The Tartarus of Maids," the narrator gives voice to the oppressed women he observes:

As other scholars have noted, the "slave" image here has two clear connotations. One describes the exploitation of the women's physical labor, and the other describes the exploitation of the women's reproductive organs. Of course, as models of women's oppression, the two are clearly intertwined."[55]

In the end he says that the narrator is never fully able to come to terms with the contrasting masculine and feminine modalities.

Issues of sexuality have been observed in other works as well. Rosenberg notes Taji, in Mardi, and the protagonist in Pierre "think they are saving young "maidens in distress" (Yillah and Isabel) out of the purest of reasons but both are also conscious of a lurking sexual motive."[52] When Taji kills the old priest holding Yillah captive, he says,

[R]emorse smote me hard; and like lightning I asked myself whether the death deed I had done was sprung of virtuous motive, the rescuing of a captive from thrall, or whether beneath the pretense I had engaged in this fatal affray for some other selfish purpose, the companionship of a beautiful maid."[56]

In Pierre, the motive of the protagonist's sacrifice for Isabel is admitted: "womanly beauty and not womanly ugliness invited him to champion the right."[57] Rosenberg argues,

This awareness of a double motive haunts both books and ultimately destroys their protagonists who would not fully acknowledge the dark underside of their idealism. The epistemological quest and the transcendental quest for love and belief are consequently sullied by the erotic."[52]

Rosenberg says that Melville fully explores the theme of sexuality in his major epic poem, Clarel. When the narrator is separated from Ruth, with whom he has fallen in love, he is free to explore other sexual (and religious) possibilities before deciding at the end of the poem to participate in the ritualistic order marriage represents. In the course of the poem, "he considers every form of sexual orientation - celibacy, homosexuality, hedonism, and heterosexuality - raising the same kinds of questions as when he considers Islam or Democracy."[52]

Some passages and sections of Melville's works demonstrate his willingness to address all forms of sexuality, including the homoerotic, in his works. Commonly noted examples from Moby-Dick are the "marriage bed" episode involving Ishmael and Queequeg, which is interpreted as male bonding; and the "Squeeze of the Hand" chapter, describing the camaraderie of sailors' extracting spermaceti from a dead whale.[58] Rosenberg notes that critics say that "Ahab's pursuit of the whale, which they suggest can be associated with the feminine in its shape, mystery, and in its naturalness, represents the ultimate fusion of the epistemological and sexual quest."[52] In addition, he notes that Billy Budd's physical attractiveness is described in quasi-feminine terms: "As the Handsome Sailor, Billy Budd's position aboard the seventy-four was something analogous to that of a rustic beauty transplanted from the provinces and brought into competition with the highborn dames of the court."[52]

Law and literature

In recent years, Billy Budd has become a central text in the field of legal scholarship known as law and literature. In the novel, Billy, a handsome and popular young sailor is impressed from the merchant vessel Rights of Man to serve aboard H.M.S. Bellipotent in the late 1790s, during the war between Revolutionary France and Great Britain. He excites the enmity and hatred of the ship's master-at-arms, John Claggart. Claggart accuses Billy of phony charges of mutiny and other crimes, and the Captain, the Honorable Edward Fairfax Vere, brings them together for an informal inquiry. At this encounter, Billy strikes Claggart in frustration, as his stammer prevents him from speaking. The blow catches Claggart squarely on the forehead and, after a gasp or two, the master-at-arms perishes.

Vere immediately convenes a court-martial, at which, after serving as sole witness and as Billy's de facto counsel, Vere urges the court to convict and sentence Billy to death. The trial is recounted in chapter 21, the longest chapter in the book. It has become the focus of scholarly controversy: was Captain Vere a good man trapped by bad law, or did he deliberately distort and misrepresent the applicable law to condemn Billy to death? [59]

Legacy

- In 1985, the New York City Herman Melville Society gathered at 104 East 26th Street to dedicate the intersection of Park Avenue south and 26th Street as Herman Melville Square. This is the street where Melville lived from 1863 to 1891 and where, among other works, he wrote Billy Budd.[60]

- In 2010 it was announced that a new species of extinct giant sperm whale, Livyatan melvillei was named in honor of Melville. The paleontologists who discovered the fossil were all fans of Moby-Dick and decided to dedicate their discovery to the author.[61][62]

Selected bibliography

- Typee: A Peep at Polynesian Life (1846)

- Omoo: A Narrative of Adventures in the South Seas (1847)

- Mardi: And a Voyage Thither (1849)

- Redburn: His First Voyage (1849)

- White-Jacket; or, The World in a Man-of-War (1850)

- Moby-Dick; or, The Whale (1851)

- Pierre: or, The Ambiguities (1852)

- Isle of the Cross (1853 unpublished, and now lost)

- "Bartleby, the Scrivener" (1853) (short story)

- The Encantadas, or Enchanted Isles (1854) (novella, possibly incorporating a short rewrite of the lost Isle of the Cross[63])

- "Benito Cereno" (1855)

- Israel Potter: His Fifty Years of Exile (1855)

- The Confidence-Man: His Masquerade (1857)

- Battle Pieces and Aspects of the War (1866) (poetry collection)

- The Martyr (1866) one of poems in a collection, on the death of Lincoln

- Clarel: A Poem and Pilgrimage in the Holy Land (1876) (epic poem)

- John Marr and Other Sailors (1888) (poetry collection)

- Timoleon (1891) (poetry collection)

- Billy Budd, Sailor (An Inside Narrative) (1891 unfinished, published posthumously in 1924; authoritative edition in 1962)

References and further reading

- Adler, Joyce (1981). War in Melville's Imagination. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-0575-8.

- Arvin, Newton (1950). Herman Melville. New York: Sloan; rpr New York: Grove ISBN 0-8021-3871-3.

- Bryant, John (1986). A Companion to Melville Studies. Westport: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-23874-X.

- Bryant, John (1993). Melville and Repose: The Rhetoric of Humor in the American Renaissance. Oxford Oxfordshire: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-507782-2.

- Chamberlain, Ray (1985). Monsieur Melville. City: Coach House Pr. ISBN 0-88910-239-2.

- Delbanco, Andrew (2005). Melville, His World and Work. New York: Knopf. ISBN 0-375-40314-0.

- Edinger, Edward (1985). Melville's Moby Dick: An American Nekyia (Studies in Jungian Psychology By Jungian Analysts). New Haven: Inner City Books. ISBN 978-0-919123-70-0.

- Garner, Stanton (1993). The Civil War World of Herman Melville. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-0602-5.

- Goldner, Loren (2006). Herman Melville: Between Charlemagne and the Antemosaic Cosmic Man. Race, Class and the Crisis of Bourgeois Ideology in an American Renaissance Writer. Cambridge: Queequeg Publications. ISBN 0-9700308-2-7.

- Gretchko, John M. J. (1990). Melvillean Ambiguities. Cleveland: Falk & Bright.

- Hardwick, Elizabeth (2000). Herman Melville. New York: Viking. ISBN 0-670-89158-4.

- Hayford, Harrison (2003). Melville's Prisoners. Evanston: Northwestern University Press. ISBN 0-8101-1973-0.

- Johnson, Bradley A. (2011). The Characteristic Theology of Herman Melville: Aesthetics, Politics, Duplicity. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock. ISBN 978-1-61097-341-0.

- Levine, Robert (1998). The Cambridge Companion to Herman Melville. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-55571-X.

- Martin, Robert (1986). Hero, Captain, and Stranger: Male Friendship, Social Critique, and Literary Form in the Sea Novels of Herman Melville. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-1672-8.

- Miller, Perry (1956). The Raven and the Whale: The War of Words and Wits in the Era of Poe and Melville. New York: Harvest Book.

- Parini, Jay (2010). The Passages of H.M.: A novel of Herman Melville. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-52277-9.

- Parker, Hershel (1996). Herman Melville: A Biography. Volume I, 1819–1851. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-5428-8.

- Parker, Hershel (2005). Herman Melville: A Biography. Volume II, 1851–1891. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-8186-2.

- Renker, Elizabeth (1998). Strike through the Mask: Herman Melville and the Scene of Writing. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-5875-5.

- Robertson-Lorant, Laurie (1996). Melville: A Biography. New York: Clarkson Potter/Publishers. ISBN 0-517-59314-9.

- Rogin, Michael (1983). Subversive Genealogy: The Politics and Art of Herman Melville. New York: Knopf. ISBN 0-394-50609-X.

- Rosenberg, Warren (1984). "'Deeper than Sappho': Melville, Poetry, and the Erotic". Modern Language Studies 14 (1).

- Spark, Clare L. (2001). Hunting Captain Ahab: Psychological Warfare and the Melville Revival (rev.ed. paperback 2006 ed.). Kent: Kent State University Press. ISBN 0-87338-888-7.

- Sullivan, Wilson (1972). New England Men of Letters. New York: Atheneum. ISBN 0-02-788680-8.

- Szendy, Peter (2009). Prophecies of Leviathan. Reading Past Melville. New York: Fordham University Press. ISBN 978-0-8232-3154-6.

- Weisberg, Richard (1984). The Failure of the Word: The Lawyer as Protagonist in Modern Fiction. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-04592-1.

Notes

- ↑ Originally spelled "Melvill", after the death of Melville's father in 1832 his mother added an "e" to the family surname—seemingly at the behest of her son Gansevoort.[1]

- ↑ Reproduced in The Melville Log (1951), a two-volume collection of Melville-related documents assembled by Jay Leyda, intended to provide as much of a day-to-day account of Melville's life as possible.

- ↑ This would have been the Statenvertaling of 1637, the Dutch equivalent of the King James Bible.

Footnotes

- ↑ Levine, Robert Steven (1998). The Cambridge Companion to Herman Melville. Cambridge University Press. pp. xv; 112. ISBN 0-521-55477-2.

- ↑ Life years of the Melville family: Genealogical chart in Parker 2002, 926-929.

- ↑ Cited in Andrew Delbanco, Melville: His World and Work. Alfred A Knopf, New York 2005, 20.

- ↑ Delbanco, 19.

- ↑ Delbanco, 17.

- ↑ Parker, Vol. I, 12

- ↑ Delbanco, 21-22, quotation on 21.

- ↑ Robertson-Lorant, 33

- ↑ Cited in Merton M. Sealts, Jr., Melville's Reading. Revised and Enlarged Edition, University of South Carolina Press, 1988, 17.

- ↑ Sealts 1988, 17.

- ↑ Herman Melville, Correspondence. Edited by Lynn Horth. The Writings of Herman Melville Volume Fourteen, Northwestern University Press and The Newberry Library, Evanston and Chicago 1993, 4.

- ↑ Melville 1993, 5.

- ↑ Sealts, 17.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Sullivan, 117

- ↑ David K. Titus, "Herman Melville at the Albany Academy", Melville Society Extracts, May 1980, no. 42, pp. 1, 4-10. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- ↑ Sealts, 18.

- ↑ Titus, 8.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Sealts, 20.

- ↑ See Redburn, pg. 82: "For sailors are of three classes able-seamen, ordinary-seamen, and boys... In merchant-ships, a boy means a green-hand, a landsman on his first voyage."

- ↑ Kathleen LaFrank (May 1992). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Herman Melville House". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Retrieved 2011-01-13.

- ↑ Parker, Vol. 1, 185

- ↑ Miller, 5

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Delbanco, 66

- ↑ Delbanco, 91–92

- ↑ Delbanco, 124

- ↑ Walter E. Bezanson, "Moby-Dick: Document, Drama, Dream," in John Bryant (ed.), A Companion to Melville Studies, Greenwood Press, 1986, 180.

- ↑ In an essay on Hawthorne's Mosses in the Literary Review (August 1850), Melville wrote:

To what infinite height of loving wonder and admiration I may yet be borne, when by repeatedly banquetting on these Mosses, I shall have thoroughly incorporated their whole stuff into my being,--that, I can not tell. But already I feel that this Hawthorne has dropped germinous seeds into my soul. He expands and deepens down, the more I contemplate him; and further, and further, shoots his strong New-England roots into the hot soil of my Southern soul.

- ↑ Cheever, Susan (2006). American Bloomsbury: Louisa May Alcott, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Margaret Fuller, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Henry David Thoreau; Their Lives, Their Loves, Their Work. Detroit: Thorndike Press. p. 196. ISBN 0-7862-9521-X.

- ↑ Parker, Vol. I, 131–132

- ↑ Nathaniel Hawthorne, entry for 20 November 1856, in The English Notebooks, (1853 - 1858)

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 "Herman Melville On Clarel, Holy Land". Shapell Manuscript Collection. Shapell Manuscript Foundation.

- ↑ Robertson-Lorant (1996), pp 375-400

- ↑ Watson G. Branch,ed., Herman Melville: The Critical Heritage (London and New York: Routledge, 1997). Reviews of The Confidence-Man begin at p. 369.)

- ↑ Kennedy, Frederick James (March 1977). "Herman Melville's Lecture in Montreal". The New England Quarterly 50 (1): 125–137. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ↑ Leyda, Jay (1969). The Melville Log 2. New York: Gordian Press. p. 730. "quietly declining offers of money for special services, quietly returning money which has been thrust into his pockets"

- ↑ "Dreamland: American Travelers to the Holy Land in the 19th Century". Shapell Manuscript Foundation.

- ↑ Delbanco, 319

- ↑ Parker, vol. 2, 921

- ↑ Delbanco, 7

- ↑ Delbanco, 294

- ↑ Riegel, O.W. (May 1931). "The Anatomy of Melville's Fame". American Literature 3 (2): 195–203. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ↑ Nathalia Wright, "Melville and STW at Yale: Studies under Stanley T. Williams." Melville Society Extracts, 70 (September 1987), 1-4.

- ↑ Collected Poems of Herman Melville, Ed. Howard P. Vincent. Chicago: Packard & Company and Hendricks House (1947), 446.

- ↑ p. 287, Andrew Delbanco (2005), Melville: His World and Work. New York: Knopf. ISBN 0-375-40314-0

- ↑ Lawrence Buell, “Melville The Poet,” in Robert Levine, ed., The Cambridge Companion to Melville (Cambridge University Press, 1998), p. 135.

- ↑ Renker, Elizabeth (Spring–Summer 2000). "Melville the Poet: Response to William Spengemann". American Literary History 12 (1&2). Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- ↑ Spanos, William V. (2009). Herman Melville and the American Calling: The Fiction After Moby-Dick, 1851-1857. SUNY Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-7914-7563-8.

- ↑ Chapin, Henry Introduction John Marr & Other Poems kindle ebook ASIN B0084B7NOC

- ↑ Melville, Herman (1995). "Introduction". In Helen Vendler. Selected Poems of Herman Melville. San Francisco: Arion Press. pp. xxv.

- ↑ Serlin, David Harley. "The Dialogue of Gender in Melville's The Paradise of Bachelors and the Tartarus of Maids", Modern Language Studies 25.2 (1995): 80-87. Note: These two writings are separate but often read together for the full effect of Melville's purpose. In both these works many phallic symbols are represented (such as the swords and snuff powder which represented a lack of semen in the bachelors.) Not only this, but in the 'Tartarus of Maids' there was a detailed description of how the main character arrived at the 'Tartarus of Maids.' This description was intended to resemble that of the vaginal canal.

- ↑ James Creech, Closet writing: The case of Melville's Pierre, 1993

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 52.3 52.4 52.5 52.6 Rosenberg, 70-78

- ↑ see Delblanco, Andrew. American Literary History, 1992

- ↑ Sandberg, Alvin. "Erotic Patterns in 'The Paradise of Bachelors and the Tartarus of Maids', " Literature and Psychology 18.1 (1968): 2-8.

- ↑ Serlin, David Harley. "The Dialogue of Gender in Melville's The Paradise of Bachelors and the Tartarus of Maids", Modern Language Studies 25.2 (1995): 80-87

- ↑ Melville, Herman. Mardi, ed. Tyrus Hillway. New Haven: College and University Press, 1973. p. 132.

- ↑ Melville, Herman. Pierre, New York: Grove Press, 1957. p. 151.

- ↑ E. Haviland Miller, Melville, New York, 1975.

- ↑ Weisberg, Richard H. The Failure of the Word: The Lawyer as Protagonist in Modern Fiction (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1989), chapters 8 and 9.

- ↑ HERBERT MITGANG (1985-05-12). "VOYAGING FAR AND WIDE IN SEARCH OF MELVILLE". The New York Times. Retrieved 2011-03-15.

- ↑ Janet Fang (2010-06-30). "Call me Leviathan melvillei". Nature. Retrieved 2010-06-30.

- ↑ Pallab Ghosh (2010-06-30). "'Sea monster' whale fossil unearthed". BBC. Retrieved 2010-06-30.

- ↑

External links

| Find more about Herman Melville at Wikipedia's sister projects | |

| |

Definitions and translations from Wiktionary |

| |

Media from Commons |

| |

Quotations from Wikiquote |

| |

Source texts from Wikisource |

| |

Textbooks from Wikibooks |

| |

Learning resources from Wikiversity |

- Hershel Parker, Herman Melville: A Biography, Vol. 1 (1891-1851) The first 150 pages are online.

- Arrowhead—The Home of Herman Melville

- Physical description of Melville from his 1856 passport application

- Melville's page at Literary Journal.com: research articles on Melville's works

- Melville Room at the Berkshire Athenaeum

- New Bedford Whaling Museum

- Melville's Marginalia Online A digital archive of books that survive from Herman Melville's library with his annotations and markings.

- The Confidence Man: His Masquerade ed. Scott Atkins with critical introduction, historical contexts, and new footnotes from American Studies at the University of Virginia.

- Billy Budd: Foretopman ed. David Padilla with extensive linked footnotes and glossary of terms from American Studies at the University of Virginia

- The Language of Gesture: Melville's Imaging of Blackness and the Modernity of Billy Budd by Klaus Benesch

- The Encantadas from American Studies at the University of Virginia

- The Life and Works of Herman Melville

- The Melville Society

- Works by Herman Melville at Project Gutenberg

-

Herman Melville public domain audiobooks from LibriVox

Herman Melville public domain audiobooks from LibriVox - Works by or about Herman Melville in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Melville index entry at Poets' Corner

- Contemporary views on Herman Melville

- "Into the Deep: America, Whaling & the World", PBS, American Experience, 2010. Cf. section on Melville.

- "The True-Life Horror that Inspired Moby Dick," Past Imperfect, Smithsonian.com, March 1, 2013

- Antiquarian Booksellers' Association of America: Collecting Herman Melville

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||

|