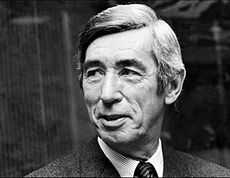

Hergé

| Hergé | |

|---|---|

Hergé | |

| Born |

Georges Prosper Remi 22 May 1907 Etterbeek, Belgium |

| Died |

3 March 1983 (aged 75) Woluwe-Saint-Lambert, Belgium |

| Nationality | Belgian |

| Area(s) | Cartoonist |

| Pseudonym(s) | Hergé |

Notable works | |

| Awards | List of awards |

| Signature | |

|

| |

|

Official website | |

Georges Prosper Remi (French: [ʁəmi]; 22 May 1907 – 3 March 1983), known by the pen name Hergé ([ɛʁʒe]), was a Belgian cartoonist. His best known and most substantial work is the 23 completed comic books in The Adventures of Tintin series, which he made from 1929 until his death in 1983. He was also responsible for two other well-known series, Quick & Flupke (1930–40) and Jo, Zette and Jocko (1936–57). His works were executed in his distinct ligne claire drawing style.

Born to a lower-middle-class family in Etterbeek, Brussels, Hergé took a keen interest in Scouting, producing both illustrations and the Totor series for Scouting and Catholic magazines. In 1925 he started work for conservative newspaper Le Vingtième Siècle ("The Twentieth Century"), where under the influence of Norbert Wallez, in 1929 he began serialising the first of his stories to feature boy reporter Tintin, Tintin in the Land of the Soviets. Domestically successful, he continued with further Adventures of Tintin and the Quick & Flupke series at the paper, but from The Blue Lotus onward placed a far greater emphasis on background research. After Le Vingtième Siècle was closed during the occupation by Nazi Germany, Hergé continued work for Le Soir; after liberation, he faced accusations of being a collaborator, but was exonerated, and proceeded to oversee the creation of Tintin magazine, through which he remained artistic director over Studio Hergé until his death.

Hergé's works have been widely acclaimed for their clarity of draughtsmanship and meticulous, well-researched plots, and have been the source of a wide range of adaptations. He remains a strong influence on the comic book medium, particularly in Europe.[1][2] Since 2009, the Hergé Museum (Musée Hergé) has been open in Louvain-La-Neuve, honouring the world of Tintin and Hergé.[3]

Early life

Childhood: 1907–25

Georges Prosper Remi was born on 22 May 1907 in his parental home in Etterbeek, Brussels, a central suburb in the capital city of Belgium.[4] His father, the Wallonian Alexis Remi, worked in a candy factory, whilst his mother, the Flemish Elisabeth Dufour, was a homemaker.[5] Married on 18 January 1905, they moved into a house at 25, de la rue Cranz (now 33, rue Philippe Baucq), where Hergé was born, although a year later they moved to a house at 34, rue de Theux.[4] His primary language was his father's French, but growing up in the bilingual Brussels, he also learned Flemish, developing a Marollien accent from his maternal grandmother.[6] Like most Belgians, his family belonged to the Roman Catholic Church, though were not particularly devout.[7] He later characterised his life in Etterbeek as being dominated by a monochrome gray, considering it extremely boring.[8] Biographer Benoît Peeters suggested that this childhood melancholy might have been exacerbated through being sexually abused by a maternal uncle.[9]

"My childhood was extremely ordinary. It happened in a very average place, with average events and average thoughts. For me, the poet's "green paradise" was rather gray... My childhood, my adolescence, Boy Scouting, military service – all of it was gray. Neither a sad boyhood nor a happy one – rather a lackluster one."

Remi developed a love of cinema, favouring Winsor McCay's Gertie the Dinosaur and the films of Charlie Chaplin, Harry Langdon and Buster Keaton; his later work in the comic strip medium displayed an obvious influence from them in style and content.[11] Although not a keen reader, he enjoyed the novels of British and American authors, such as Huckleberry Finn, Treasure Island, Robinson Crusoe and The Pickwick Papers, as well as the novels of Frenchman Alexandre Dumas.[12] Drawing as a hobby, he sketched out scenes from daily life along the edges of his school books. Some of these illustrations were of German soldiers, because his four years of primary schooling at the Ixelles Municipal School No. 3 coincided with the First World War, during which Brussels was occupied by the German Empire.[13] In 1919, his secondary education began at the secular Place de Londres in Ixelles,[14] but in 1920 he was moved to Saint-Boniface School, an institution controlled by the archbishop where the teachers were Roman Catholic priests.[15] Remi proved a successful student, being awarded prizes for excellence and would ultimately finish his secondary education in July 1925 as the top of his class.[16]

Aged 12, Remi joined the Boy Scout brigade attached to Saint-Boniface School, becoming troop leader of the Squirrel Patrol and earning the name "Curious Fox" (Renard curieux).[17] With the Scouts, he travelled for summer camps in Italy, Switzerland, Austria and Spain, and in the summer of 1923 his troop hiked 200 miles across the Pyrenees.[18] His experiences with Scouting would have a significant influence on the rest of his life, sparking his love of camping and the natural world, and providing him with a moral compass that stressed personal loyalty and keeping one's promise.[19] His Scoutmaster, Rene Weverbergh, encouraged his artistic ability, and published one of Remi's drawings in the newsletter of the Saint-Boniface Scouts, Jamais Assez (Never Enough); his first published work.[20] When Weverbergh became involved in the publication of Boy-Scout, the newsletter of the Federation of Scouts, he published more of Remi's illustrations, the first of which appeared in the fifth issue, from 1922.[20] Remi continued publishing cartoons, drawings and woodcuts in subsequent issues of the magazine, which was soon renamed Le Boy-Scout Belge (The Belgian Boy Scout). During this time, he experimented with different pseudonyms, using "Jérémie" and "Jérémiades" before settling on "Hergé", the pronunciation of his reversed initials (R.G.), a name that he first published under in December 1924.[21]

Totor and early career: 1925–28

Alongside his stand-alone illustrations, in July 1926 Hergé began production of a comic strip for Le Boy-Scout Belge, Les Aventures de Totor, C.P. des Hannetons (The Adventure of Totor C.P. of the June Bugs), which continued intermittent publication until 1929. Revolving around the adventures of a Boy Scout patrol leader, the comic initially featured written captions underneath the scenes, but Hergé began to experiment with other forms of conveying information, including speech bubbles.[22] Illustrations were also published in Le Blé qui lève (The Wheat That Grows) and other publications of the Catholic Association of Belgian Young People, and Hergé produced a book jacket for Weverbergh's novel, The Soul of the Sea.[23] Being young and inexperienced, still learning his craft, Hergé sought guidance from an older cartoonist, Pierre Ickx, and together they founded the short lived Atelier de la Fleur de Lys (AFL), an organisation for Christian cartoonists.[24]

After graduating from secondary school in 1925, Hergé enrolled in the École Saint-Luc art school, but finding the teaching boring, he left after one lesson.[25] Hoping for an illustrative job alongside Ickx at Le Vingtième Siècle (The Twentieth Century) – an ultra-conservative "Catholic Newspaper of Doctrine and Information" – he found there to be no positions available, instead obtaining a job in the paper's subscriptions department, starting work there in September 1925.[26] Despising the boredom of this position, he enlisted for military service before he was called up, and in August 1926 was assigned to the Dailly barracks at Schaerbeek. Joining the first infantry regiment, he was also bored by his military training, but continued sketching and producing episodes of Totor.[27] Toward the end of his military service, in August 1927, Hergé met with the editor of Le XXe Siecle, the Abbé Norbert Wallez, a vocal fascist known for the signed picture of Italian Fascist leader Benito Mussolini that he kept on his desk.[28] Impressed by Hergé's repertoire, Wallez agreed to give him a job as a photographic reporter and cartoonist for the paper, something for which Hergé always remained grateful, coming to view the Abbé as a father figure.[29] Supplemented by commissions for other publications, Hergé illustrated a number of texts for "The Children's Corner" and the literary pages; the illustrations of this period show his interest in woodcuts and the early prototype of his ligne claire style.[30]

Founding Tintin and Quick & Flupke: 1929–32

Beginning a series of newspaper supplements in late 1928, Wallez founded a supplement for children, Le Petit Vingtième (The Little Twentieth), which subsequently appeared in Le Vingtième Siècle every Thursday.[31] Carrying strong Catholic and fascist messages, many of its passages were explicitly anti-semitic.[32] For this new venture, Hergé illustrated L'Extraordinaire Aventures de Flup, Nénesse, Puosette et Cochonet (The Extraordinary Adventures of Flup, Nénesse, Puosette and Cochonet), a comic strip authored by one of the paper's sport columnists, which told the story of two boys, one of their little sisters, and her inflatable rubber pig.[33] Hergé was unsatisfied, and eager to write and draw a comic strip of his own. He was fascinated by new techniques in the medium – such as the systematic use of speech bubbles – found in such American comics as George McManus' Bringing up Father, George Herriman's Krazy Kat and Rudolph Dirks's Katzenjammer Kids, copies of which had been sent to him from Mexico by the paper's reporter Léon Degrelle, stationed there to report on the Cristero War.[34]

Hergé developed a character named Tintin as a Belgian boy reporter who could travel the world with his fox terrier, Snowy – "Milou" in the original French – basing him in large part on his earlier character of Totor and also on his own brother, Paul.[35] Degrelle later falsely claimed that Tintin had been based on him, while he and Hergé fell out when Degrelle used one of his designs without permission; they settled out-of-court.[36] Although Hergé wanted to send his character to the United States, Wallez instead ordered him to set his adventure in the Soviet Union, acting as a work of anti-socialist propaganda for children. The result, Tintin in the Land of the Soviets, began serialisation in Le Petit Vingtième on 10 January 1929, and ran until 8 May 1930.[37] Popular in Francophone Belgium, Wallez organized a publicity stunt at the Gare de Nord station, following which he organized the publication of the story in book form.[38] The popularity of the story led to an increase in sales, and so Wallez granted Hergé two assistants, Eugène Van Nyverseel and Paul "Jam" Jamin.[39]

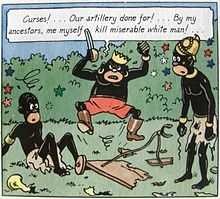

In January 1930, Hergé introduced Quick & Flupke (Quick et Flupke), a new comic strip about two street kids from Brussels, in the pages of Le Petit Vingtième.[40] At Wallez's direction, in June he began serialisation of the second Tintin adventure, Tintin in the Congo, designed to encourage colonial sentiment towards the Belgian Congo. Authored in a paternalistic style that depicted the Congolese as childlike idiots, in later decades it would be accused of racism, however at the time was un-controversial and popular, with further publicity stunts held to increase sales.[41] For the third adventure, Tintin in America, serialised from September 1931 to October 1932, Hergé finally got to deal with a scenario of his own choice, although used the work to push an anti-capitalist, anti-consumerist agenda in keeping with the paper's ultra-conservative ideology.[42] Although the Adventures of Tintin had been serialised in the French Catholic Coeurs Vaillants ("Valiant Hearts") since 1930, he was soon receiving syndication requests from Swiss and Portuguese newspapers too.[43] Though wealthier than most Belgians his age and with increasing success, he remained unfazed, being a "conservative young man" dedicated to his work.[44]

Hergé sought work elsewhere too, creating The Lovable Mr. Mops cartoon for the Bon Marché department store,[45] and The Adventures of Tim the Squirrel Out West for the rival L'Innovation department store.[46] On 20 July 1932, he married Germaine Kieckens, who was Wallez's secretary; although neither of them were entirely happy with the union, they had been encouraged to do so by Wallez, who demanded that all his staff married and who personally carried out the wedding ceremony at the Saint-Roch Church in Laeken.[47] Spending their honeymoon in Vianden, Luxembourg, the couple moved into an apartment in the rue Knapen, Schaerbeek.[48] When Wallez was removed from the paper's editorship following a scandal, Hergé tried to resign, but was encouraged to stay after his monthly salary was increased from 2000 and 3000 francs and his workload was reduced, with Jamin taking responsibility for the day-to-day running of Le Petit Vingtième.[49]

Rising fame

Tintin in the Orient and Jo, Zette & Jocko: 1932–39

In November 1932 Hergé announced that the following month he would send Tintin on an adventure to Asia.[50] Although initially titled The Adventures of Tintin, Reporter, in the Orient, it would later be renamed Cigars of the Pharaoh. A mystery story, the plot began in Egypt before proceeding to Arabia and India, during which the recurring characters of Thomson and Thompson and Roberto Rastapopoulos were introduced.[51] Through his friend Charles Lesne, Hergé was hired to produce illustrations for the company Casterman, and in late 1933 they proposed taking over the publication of both The Adventures of Tintin and Quick and Couple in book form, to which Hergé agreed; the first Casterman book was the collected volume of Cigars.[52] Continuing to subsidise his comic work with commercial advertising, in January 1934 he also founded the "Atelier Hergé" advertising company with two partners, but it was liquidated after six months.[53] From February to August 1934 Hergé serialised Popol out West in Le Petit Vingtième, a story using animal characters that was a development of the earlier Tim the Squirrel comic.[54]

From August 1934 to October 1935, Le Petit Vingtième serialised Tintin's next adventure, The Blue Lotus, which was set in China and dealt with the recent Japanese invasion of Manchuria. Hergé had been greatly influenced in the production of the work by his friend Zhang Chongren, a Catholic Chinese student studying at Brussels' Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts, whom he had been introduced to in May 1934. Zhang gave him lessons in Taoist philosophy, Chinese art, and Chinese calligraphy, influencing not only his artistic style but also his general outlook on life.[55] As a token of appreciation Hergé added a fictional "Chang Chong-Chen" to The Blue Lotus, a young Chinese boy who meets and befriends Tintin.[56] For The Blue Lotus, Hergé devoted far more attention to accuracy, resulting in a largely realistic portrayal of China.[57] As a result, The Blue Lotus has been widely hailed as "Hergé's first masterpiece" and a benchmark in the series' development.[58] Casterman published it in book form, also insisting that Hergé include colour plates in both the volume and in reprints of America and Cigars.[59] In 1936, they also began production of Tintin merchandise, something Hergé supported, having ideas of an entire shop devoted to The Adventures of Tintin, something that would come to fruition 50 years later.[60] Nevertheless, while his serialised comics proved lucrative, the collected volumes sold less well, something Hergé blamed on Casterman, urging them to do more to market his books.[61]

Hergé's next Tintin story, The Broken Ear, was the first for which the plot synopsis had been outlined from the start, being a detective story that took Tintin to South America. It introduced the character of General Alcazar, and also saw Hergé introduce the first fictional countries into the series, San Theodoros and Nuevo Rico, two republics based largely on Bolivia and Paraguay.[62] The violent elements within The Broken Ear upset the publishers of Cœurs Vaillants, who asked Hergé to create a more child-appropriate story for them. The result was The Adventures of Jo, Zette, and Jocko, a series about a young brother and sister and their pet monkey.[63] The series began with The Secret Ray, which was serialised in Cœurs Vaillants and then Le Petit Vingtième, and continued with The Stratoship H-22.[64] Hergé nevertheless disliked the series, commenting that the characters "bored me terribly."[65] Now writing three series simultaneously, Hergé was working every day of the year, and felt stressed.[66]

The next Tintin adventure was The Black Island.

German occupation and Le Soir: 1939–45

In the Second World War, Hergé was mobilized as a reserve lieutenant, and had to interrupt Tintin's adventures in the middle of Land of Black Gold.[67] Prior to the invasion of neutral Belgium by German forces, Hergé published humoristic drawings in L'Ouest, a paper run by future collaborator Raymond de Becker and which strongly advocated that Belgium not join the war alongside its World War One allies France and Britain.[68] By the summer of 1940 Belgium had fallen to Germany along with most of Western Continental Europe.

Le Petit Vingtième, in which Tintin's adventures had until then been published, was shut down by the Nazi occupiers.[69] However, Hergé accepted an offer to produce a new Tintin strip in Le Soir, Brussels' leading French daily, which had been appropriated as the mouthpiece of the occupation forces.[70] He left Land of the Black Gold unfinished, launching instead into The Crab with the Golden Claws, the first of six Tintin stories which he produced during the war.

As the war progressed, two factors arose that led to a revolution in Hergé's style. Firstly, paper shortages forced Tintin to be published in a daily three- or four-frame strip, rather than the two full pages every week which had been the practice on Le Petit Vingtième.[71] In order to create tension at the end of each strip rather than the end of each page, Hergé had to introduce more frequent gags and faster-paced action. Secondly, Hergé had to move the focus of Tintin's adventures away from current affairs, in order to avoid controversy. He turned to stories with an escapist flavour: an expedition to a meteorite (The Shooting Star), an intriguing mystery and treasure hunt (The Secret of the Unicorn and Red Rackham's Treasure), and a quest to undo an ancient Inca curse (The Seven Crystal Balls and Prisoners of the Sun).

In these stories Hergé placed more emphasis on characters than plot, and indeed Tintin's most memorable companions, Captain Haddock and Cuthbert Calculus (in French Professeur Tryphon Tournesol), were introduced at this time. Haddock debuted in The Crab with the Golden Claws and Calculus in Red Rackham's Treasure.

The Shooting Star was nonetheless controversial. The story line involved a race between two ship crews trying to reach a meteorite which had landed in the Arctic. Hergé chose a subject that was as fantastic as possible rather than issues related to the crisis of the times to avoid trouble with the censors. Nonetheless politics intruded. The crew Tintin joined was composed of Europeans from Axis or neutral countries ("Europe") while their underhanded rivals were Americans (although in later editions the US flag was removed from the rival ship; see the image on the The Shooting Star page), financed by a person with a Jewish name and what Nazi propagandists called "Jewish features."[72] Tintin also flies in a German Arado Ar 196 plane.

In a scene which appeared when the story was being serialised in Le Soir, two Jews, depicted in classic anti-Semitic caricature, are shown watching Philippulus the prophet harassing Tintin. One actually looks forward to the end of the world, arguing that it would mean that he would not be obliged to settle with his creditors (see the image on the Ideology of Tintin page).

In 1943 Hergé met Edgar P. Jacobs, another comics artist, whom he hired to help revise the early Tintin albums.[73] Jacobs' most significant contribution would be his redrawing of the costumes and backgrounds in the revised edition of King Ottokar's Sceptre which gave it a Balkan feel - in the original, the castle guards had been dressed as British Beefeaters. Jacob also began collaborating with Hergé on a new Tintin adventure, The Seven Crystal Balls (see above).

During and after the German occupation Hergé was accused of being a collaborator because of the Nazi control of the paper (Le Soir), and he was briefly taken in for interrogation after the war.[74] He claimed that he was simply doing a job under the occupation, like a plumber or carpenter.

After the war Hergé admitted that: "I recognize that I myself believed that the future of the West could depend on the New Order. For many, democracy had proved a disappointment, and the New Order brought new hope. In light of everything which has happened, it is of course a huge error to have believed for an instant in the New Order."[75] The Tintin character was never depicted as adhering to these beliefs. However, it has been argued that anti-Semitic themes continued, especially in the depiction of Tintin's enemy Rastapopoulos in the post-war Flight 714,[76] though other writers argue against this, pointing out the way that Rastapopoulos surrounds himself with explicitly German-looking characters: Kurt, the submarine (or u-boat) commander of The Red Sea Sharks, Doctor Krollspell, whom Hergé himself referred to as a former concentration camp official, and Hans Boehm, the sinister-looking navigator and co-pilot, both from Flight 714.[77]

Post-war troubles: 1944–45

The occupation of Brussels ended on 3 September 1944. Tintin's adventures were interrupted toward the end of The Seven Crystal Balls when the Allied authorities shut down Le Soir.[78] During the chaotic post-occupation period, Hergé was arrested four times by different groups.[79] He was publicly accused of being a Nazi/Rexist sympathizer, a claim which was largely unfounded, as the Tintin adventures published during the war were scrupulously free of politics (the only dubious point occurring in The Shooting Star, discussed above). In fact, one or two stories published before the war had been critical of fascism; most prominently, King Ottokar's Sceptre showed Tintin working to defeat a coup attempt that could be seen as an allegory of the Anschluss, Nazi Germany's takeover of Austria. Nevertheless, like other former employees of the Nazi-controlled press, Hergé found himself barred from newspaper work. He spent the next two years working with Jacobs, as well as a new assistant, Alice Devos, adapting many of the early Tintin adventures into colour.[80]

Tintin's exile ended on 26 September 1946. The publisher and wartime resistance fighter Raymond Leblanc provided the financial support and anti-Nazi credentials to launch the Franco-Belgian comics magazine Tintin with Hergé. The weekly publication featured two pages of Tintin's adventures, beginning with the remainder of The Seven Crystal Balls, as well as other comic strips and assorted articles.[81] It became highly successful, and weekly circulation surpassed 100,000.

Tintin had always been credited as simply "by Hergé", without mention of Edgar Pierre Jacobs and Hergé's other assistants. As Jacobs' contribution to the production of the strip increased, he asked for a joint credit in 1944, which Hergé refused. They continued to collaborate intensely until 1946, when Jacobs went on to produce his own comics for Tintin magazine, including the widely acclaimed Blake and Mortimer.[82]

Later life

Personal crisis

The increased demands which Tintin magazine placed on Hergé began to take their toll. In 1947 Prisoners of the Sun was interrupted for two months when an exhausted Hergé took a long vacation.[83] Hergé, disillusioned by his treatment and that of many of his colleagues and friends after the war, planned to migrate with his wife Germaine to Argentina, but later abandoned the plan when he began a love affair.[84] In 1949, while working on the new version of Land of Black Gold (the first version had been left unfinished by the outbreak of World War II), Hergé suffered a nervous breakdown and was forced to take an abrupt four-month-long break.[85] He suffered another breakdown in early 1950, while working on Destination Moon.[86]

In order to lighten Hergé's workload Hergé Studios was set up on 6 April 1950.[87] The studio employed several assistants to aid Hergé in the production of The Adventures of Tintin. Foremost among these was artist Bob de Moor, who collaborated with Hergé on the remaining Tintin adventures, filling in details and backgrounds such as the spectacular lunar landscapes in Explorers on the Moon.[88] With the aid of the studio, Hergé managed to produce The Calculus Affair from 1954 until 1956, followed by The Red Sea Sharks in 1956 to 1957.

By the end of this period his personal life was again in crisis. His marriage with Germaine was breaking apart after twenty-five years; he had fallen in love with Fanny Vlamynck, a young artist who had recently joined the Hergé Studios.[89] Furthermore, he was plagued by recurring nightmares filled with whiteness.[90] He consulted a Swiss psychoanalyst, who advised him to give up working on Tintin.[91] Instead, he finished Tintin in Tibet, started the year before.

Published in Tintin magazine from September 1958 to November 1959, Tintin in Tibet sent Tintin to the Himalayas in search of Chang Chong-Chen, the Chinese boy he had befriended in The Blue Lotus. The adventure allowed Hergé to confront his nightmares by filling the book with austere alpine landscapes, giving the adventure a powerfully spacious setting. The normally rich cast of characters was pared to a minimum—Tintin, Snowy, Captain Haddock, and the Sherpa Tharkey—as the story focused on Tintin's dogged search for Chang. Hergé came to regard this highly personal and emotionally riveting Tintin adventure as his favourite.[92] The completion of the story seemed also to signal an end to his problems: he was no longer troubled by nightmares, divorced Germaine in 1977 (they had separated in 1960), and finally married Fanny Vlamynck on 20 May of the same year.[93]

Last years

The last three complete Tintin adventures were produced at a much-reduced pace: The Castafiore Emerald in 1963, Flight 714 to Sydney in 1968, and Tintin and the Picaros in 1976. However, by this time Tintin had begun to move into other media. From the start of Tintin magazine, Raymond Leblanc had used Tintin for merchandising and advertisements. In 1961 the second Tintin film was made: Tintin and the Golden Fleece, starring Jean-Pierre Talbot as Tintin[94] (an earlier stop motion-animated film was made in 1947 called The Crab with the Golden Claws, but it was screened publicly only once).[95] Several traditionally animated Tintin films have also been made, beginning with The Calculus Case in 1961.

The financial success of Tintin allowed Hergé to devote more of his time to travel. He travelled widely across Europe, and in 1971 visited America for the first time, meeting some of the Native Americans whose culture had long been a source of fascination for him.[96] In 1973 he visited Taiwan, accepting an invitation offered three decades before by the Kuomintang government, in appreciation of The Blue Lotus.[97]

In a remarkable instance of life mirroring art, Hergé managed to resume contact with his old friend Chang Chong-jen, years after Tintin rescued the fictional Chang Chong-Chen in the closing pages of Tintin in Tibet. Chang had been reduced to a street sweeper by the Cultural Revolution, before becoming the head of the Fine Arts Academy in Shanghai during the 1970s. He returned to Europe for a reunion with Hergé in 1981, and settled in Paris in 1985, where he died in 1998.[98]

Hergé died on 3 March 1983, aged 75.[99] He had been severely ill for several years, but the nature of his disease was unclear, possibly leukemia or a form of porphyria. His death was hastened by an HIV infection that he contracted during his weekly blood transfusions.[100]

He left the twenty-fourth Tintin adventure, Tintin and Alph-Art, unfinished. Following his expressed desire not to have Tintin handled by another artist, it was published posthumously as a set of sketches and notes in 1986. In 1987 Fanny closed the Hergé Studios, replacing it with the Hergé Foundation. In 1988 the Tintin magazine was discontinued.

Hergé gave all rights to the creation of dolls and merchandise after his death to Michel Aroutcheff. Michel was Hergé's neighbour and a good friend. Aroutcheff then sold on these rights only keeping the right to make Tintin's red rocket when he goes to the moon.

Hergé, art collector and painter

Hergé had a strong affinity with painting. Among the old masters, he loved Bosch, Breugel, Holbein and Ingres, whose drawings with pure lines he admired. He was also very interested in contemporary artists, such as Lichtenstein, Warhol and Miro. About Miro, he confided to his art adviser and friend Pierre Sterckx that he felt a shock the first time he saw one of his paintings. Hergé began to acquire artworks in the fifties, mainly paintings by Flemish expressionists. In the early sixties, he attended the Gallerie Carrefour of Marcel Stal and, through his contacts with artists, critics and collectors, he began to buy works from Fontana, Poliakoff and many others.

In 1962, Hergé decided he wanted to paint. He chose Louis Van Lint, one of the most respected Belgian abstract painters at the time, whose work he liked a lot, to be his private teacher. For a year, Hergé learned under Van Lint's guidance, and 37 paintings emerged, influenced by Van Lint, Miro, Poliakoff, Devan or Klee.[101] Hergé, however, eventually gave up painting, thinking that he could not fully express himself through this art form. His paintings from this period are nonetheless valued by collectors not only because they are by Hergé but also for their intrinsic qualities.

Bibliography

Only the works marked * have been translated into English

| Work | Year | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| Totor | 1926–30 | Hergé's first work, published in Le Boy Scout Belge, about a brave scout. |

| Flup, Nénesse, Poussette and Piglet | 1928 | Written by a sports reporter, published in Le Petit Vingtième |

| 'Le Sifflet' strips | 1928–29 | 7 almost forgotten one-page strips drawn by Hergé for this paper |

| The Adventures of Tintin * | 1929–83 | 24 volumes, one unfinished |

| Quick and Flupke * | 1930–40 | 12 volumes, 11 translated to English |

| early 1930s | A short series Hergé made for his small advertising company Atelier Hergé. Only 4 pages.[102] | |

| Fred and Mile | 1931 | |

| The Adventures of Tim the Squirrel out West | 1931 | |

| The Amiable Mr. Mops | 1932 | |

| The Adventures of Tom and Millie | 1933 | Two stories written. |

| Popol out West * | 1934 | |

| Dropsy | 1934 | |

| Jo, Zette and Jocko * | 1936–57 | 5 volumes |

| Mr. Bellum | 1939 | |

| Thompson and Thomson, Detectives | 1943 | Written by Paul Kinnet, appeared in Le Soir |

| They Explored the Moon | 1969 | A short comic charting the moon landings published in Paris Match |

Personal life

Hergé greatly enjoyed walking in the countryside.[103]

Political views

In his early life, Hergé was "close to the traditional right-wing" of Belgian society.[104] According to Tintinologist Harry Thompson, such political ideas were not unusual in middle-class circles in Belgium of the 1920s and early 1930s, where "patriotism, Catholicism, strict morality, discipline and naivety were so inextricably bound together in everyone's lives that right-wing politics were an almost inevitable by-product. It was a world view shared by everyone, distinguished principally by its complete ignorance of the world."[105] When Hergé took responsibility for Le Petit Vingtième, he followed Wallez's instruction and allowed the newspaper to contain explicitly pro-fascist and anti-semitic sentiment.[32] Literary critic Jean-Marie Apostolidès noted that the character of Tintin was a personification of the "New Youth" concept which was promoted by the European far right.[106] Under Wallez's guidance, the early Adventures of Tintin contained explicit political messages for its young readership. Tintin in the Land of the Soviets was a work of anti-socialist propaganda,[107] while Tintin in the Congo was designed to encourage colonialist sentiment toward the Belgian Congo,[108] and Tintin in America was designed as a work of anti-Americanism heavily critical of capitalism, commercialism, and industrialisation.[109]

Tintinologist Michael Farr asserted that Hergé had "an acute political conscience" during his earlier days, as exemplified by his condemnation of racism in the United States evident in Tintin in America.[110] Literary critic Tom McCarthy went further, remarking that Tintin in America represented the emergence of a "left-wing counter tendency" in Hergé's work that rebelled against his right-wing milieu and which was particularly critical of wealthy capitalists and industrialists.[111] This was furthered in The Blue Lotus, in which Hergé rejected his "classically right-wing" ideas to embrace an anti-imperialist stance,[112] and in a contemporary Quick & Flupke strip in which he lampooned the far right leaders of Germany and Italy, Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini.[113] Although many of his friends and colleagues did so in the mid-1930s, Hergé refused to join the far right Rexist Party, later asserting that he "had always had an aversion to it", also commenting that "To throw my heart and soil into an ideology is the opposite of who I am."[114]

Accusations of racism

Hergé has faced repeated accusations of racism due to his portrayal of various ethnic groups throughout The Adventures of Tintin. According to McCarthy, in Tintin in the Congo Hergé represented the Congolese as "good at heart but backwards and lazy, in need of European mastery."[115] Thompson commented that Hergé had not written the book to be "deliberately racist", arguing that it reflected the average early 20th century Belgian view of the Congolese, one which was more "patronising" than malevolent.[116] Indeed, it provoked no controversy at the time,[117] only coming to be perceived as racist in the latter 20th century.[118] In the following Adventure, Tintin in America, Hergé depicted members of the Blackfoot tribe of Native Americans as "gullible, even naive", though it was nevertheless "broadly sympathetic" to their culture and plight, depicting their oppression at the hands of the U.S. army.[110] In The Blue Lotus, he depicted the Japanese as militaristic and buck-toothed, which has also drawn accusations of racism.[119]

Hergé has also been accused of utilising anti-semitic stereotypes. The character of Rastapopoulos has been claimed to be based on anti-semitic stereotypes, despite Hergé's protestations that the character was Italian, and not Jewish.[120]

In contrast to his racial stereotyping, from his early years, Hergé was openly critical of racism. He lambasted the pervasive racism of U.S. society in a prelude comment to Tintin in America published in Le Petit Vingtième on 20 August 1931,[121] and ridiculed racist attitudes toward the Chinese in The Blue Lotus.[122] Peeters asserted that "Hergé was no more racist than the next man",[123] an assessment shared by Farr, who after meeting Hergé in the 1980s commented that "you couldn't have met someone who was more open and less racist".[124] In contrast, President of the International Bande Dessinée Society Laurence Grove opined that Hergé adhered to prevailing societal trends in his work, and that "When it was fashionable to be a Nazi, he was a Nazi. When it was fashionable to be a colonial racist, that's what he was."[124]

Legacy

Awards and recognition

- 1971: Adamson Awards, Sweden

- 1972: Yellow Kid "una vita per il cartooning" (lifetime award) at the festival of Lucca[125]

- 1973: Grand Prix Saint Michel of the city of Brussels

- 1999: Included in the Harvey Award Jack Kirby Hall of Fame

- 2003: Included in the Eisner Award Hall of Fame as the Judge's choice

- 2005: Included in the running for De Grootste Belg (The Greatest Belgian). In the Flemish version he ended on 24th place. In the Walloon version he came 8th.

- 2006: The Dalai Lama bestowed the International Campaign for Tibet's Light of Truth Award upon the character of Tintin.

- 2007: Selected as the main motif for a high-value commemorative coin, the 100th anniversary of Hergé's birth commemorative coin minted in 2007, with a face value of 20 euro. On the obverse there is a self-portrait of Hergé on the left. To the right of the portrait there is a portrait of Tintin. In the bottom of the coin Hergé's signature is depicted.

According to the UNESCO's Index Translationum, Hergé is the ninth-most-often-translated French-language author, the second-most-often-translated Belgian author after Georges Simenon, and the second-most-often-translated French-language comics author behind René Goscinny.[126]

1652 Hergé, an asteroid of the main belt, is named after him (see also 1683 Castafiore).

In popular culture

A cartoon version of Hergé makes a number of cameo appearances in Ellipse-Nelvana's The Adventures of Tintin TV cartoon series. An animated version of Hergé also makes a cameo appearance at the start of the 2011 performance capture film, The Adventures of Tintin: The Secret of the Unicorn (directed by Steven Spielberg and produced by Peter Jackson), where he is depicted as an artist in a marketplace in Brussels drawing a portrait of Tintin.

The Hergé Museum

The Musée Hergé is located in the centre of Louvain-la-Neuve, on the edge of a green park, Le Parc de la Source. The address is Rue du Labrador, 26 - 1348 Louvain-la-Neuve (Belgium)

This location was originally chosen for the Museum in 2001. The futuristic building was designed by Pritzker Prize-winning French architect Christian de Portzamparc. On 22 May 2007 (the centenary of the birthday of Hergé) the first stone was laid for the Hergé Museum. Two years later the Museum opened its doors to the public.

The idea of a museum dedicated to the work of Hergé can be traced back to the end of the 1970s, when Hergé was still alive. After his death in 1983, Hergé's widow, Fanny, led the efforts, undertaken at first by the Hergé Foundation and then by the new Studios Hergé, to catalogue and choose the artwork and elements that would become part of the Museum's exhibitions.

The Hergé Museum contains eight permanent galleries displaying original artwork by Hergé, and telling the story of his life and career. Although his most famous creation, Tintin, features prominently, his other comic strip characters, such as Jo, Zette and Jocko, and Quick and Flupke, are also present. The exhibitions also include examples of Hergé's diverse and prolific output as a graphic designer in the 1930s. The Museum houses a temporary exhibition gallery, which is updated every few months to host new exhibitions (with diverse titles such as Tintin, Hergé and Trains, and Into Tibet with Tintin).

References

Footnotes

- ↑ Assouline 2009, p. x.

- ↑ Tayler 2012.

- ↑ "Two New Museums for Tintin and Magritte". Time. 30 May 2009. Retrieved 30 May 2009.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Peeters 2012, p. 6.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, p. 3.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, p. 3; Peeters 2012, pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, p. 3; Thompson 1991, pp. 18; Peeters 2012, p. 8.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, pp. 3–4; Peeters 2012, p. 5.

- ↑ Peeters 2012, p. 14.

- ↑ Peeters 2012, p. 5.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, p. 7; Peeters 2012, p. 7.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, p. 5; Peeters 2012, pp. 12–13.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, p. 6; Peeters 2012, p. 8.

- ↑ Peeters 2012, pp. 10–11.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, p. 7.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, p. 8; Peeters 2012, p. 16.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, p. 8; Thompson 1991, pp. 19; Peeters 2012, p. 16.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, p. 8; Peeters 2012, pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, pp. 8–9.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Assouline 2009, p. 9; Peeters 2012, p. 16.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, p. 9; Thompson 1991, p. 20; Peeters 2012, p. 19.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, p. 9; Peeters 2012, p. 22.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, p. 15; Peeters 2012, p. 17.

- ↑ Peeters 2012, p. 18.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, p. 10; Peeters 2012, p. 20.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, p. 11; Peeters 2012, p. 20.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, p. 11; Peeters 2012, pp. 21–23.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, pp. 11–13; Peeters 2012, p. 27.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, pp. 12, 14–15; Peeters 2012, pp. 27–28.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, pp. 15–16; Peeters 2012, pp. 28–29.

- ↑ Peeters 2012, pp. 31–32.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Assouline 2009, p. 38.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, p. 16; Farr 2001, p. 12; Peeters 2012, p. 32.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, p. 17; Farr 2001, p. 18; Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 18.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, p. 19; Thompson 1991, p. 25; Peeters 2012, p. 34.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, pp. 45–46; Peeters 2012, pp. 59–60.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, pp. 22–23; Peeters 2012, pp. 34–37.

- ↑ Peeters 2012, pp. 39–41.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, pp. 32–34; Peeters 2012, pp. 42–43.

- ↑ Goddin 2008, p. 95; Assouline 2009, pp. 23–24; Peeters 2012, pp. 44–45.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, pp. 26–29; Peeters 2012, pp. 45–47.

- ↑ Thompson 1991, pp. 46–50; Assouline 2009, pp. 30–32.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, p. 35.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, p. 44; Peeters 2012, pp. 43, 48.

- ↑ Thompson 1991, p. 49; Assouline 2009, p. 25.

- ↑ Thompson 1991, p. 46; Goddin 2008, p. 89.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, pp. 33–34; Peeters 2012, pp. 47–48.

- ↑ Peeters 2012, p. 58.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, pp. 40–41; Peeters 2012, pp. 67–68.

- ↑ Peeters 2012, p. 62.

- ↑ Thompson 1991, pp. 52–57; Assouline 2009, pp. 42–44; Peeters 2012, pp. 62–65.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, pp. 40–41,44; Peeters 2012, pp. 57, 60.

- ↑ Thompson 1991, p. 49; Assouline 2009, pp. 36–37; Peeters 2012, pp. 60–61.

- ↑ Peeters 2012, p. 73.

- ↑ Thompson 1991, pp. 60–64; Farr 2001, pp. 51–59; Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, pp. 33–36; Assouline 2009, pp. 48–55; Peeters 2012, pp. 73–82.

- ↑ Thompson 1991, pp. 60–64; Farr & 2001, pp. 51–59; Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, pp. 33–36; Assouline 2009, pp. 48–55; Peeters 2012, pp. 73–82.

- ↑ Thompson 1991, pp. 60–64; Farr & 2001, pp. 51–59; Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, pp. 33–36; Assouline 2009, pp. 48–55; Peeters 2012, pp. 73–82.

- ↑ Farr 2001, p. 51; Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 35; Peeters 2012, pp. 82.

- ↑ Goddin 2008, pp. 182, 196; Assouline 2009, p. 53; Peeters 2012, pp. 79–80.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, p. 55; Peeters 2012, p. 96.

- ↑ Peeters 2012, p. 94.

- ↑ Thompson 1991; Farr & 2001; Lofficier & Lofficier 2002; Assouline 2009; Peeters 2012.

- ↑ Peeters 2012, pp. 86–87.

- ↑ Peeters 2012, p. 87.

- ↑ Peeters 2012, p. 88.

- ↑ Peeters 2012, p. 91.

- ↑ Goddin 2008, p. 256.

- ↑ Valla 2009, p. 55.

- ↑ Goddin 2008, p. 260.

- ↑ Goddin 2008, p. 261.

- ↑ Goddin 2008, p. 280.

- ↑ Frey 2008, p. 28.

- ↑ Goddin 2008, p. 290.

- ↑ Goddin 2008, p. 330.

- ↑ Haagse Post. March 1973

- ↑ Frey 2008, p. 31.

- ↑ Apostolidès 2010, p. .

- ↑ Goddin 2008, p. 325.

- ↑ Goddin 2008, p. 331.

- ↑ Goddin 2008, p. 345.

- ↑ Goddin 2008, p. 365.

- ↑ Goddin 2008, p. 373.

- ↑ Goddin 2008, p. 393.

- ↑ Goddin 2008, p. 420.

- ↑ Goddin 2008, p. 462.

- ↑ Goddin 2008, p. 489.

- ↑ Goddin 2008, p. 484.

- ↑ Goddin 2008, p. 506.

- ↑ Goddin 2008, p. 567.

- ↑ Goddin 2008, p. 632.

- ↑ Goddin 2008, p. 656.

- ↑ Goddin 2008, p. 657.

- ↑ Goddin 2008, p. 934.

- ↑ Goddin 2008, p. 695.

- ↑ Goddin 2008, p. 404.

- ↑ Goddin 2008, p. 834.

- ↑ Goddin 2008, p. 887.

- ↑ Tintin's new adventure in HollywoodThe First Post

- ↑ Goddin 2008, p. 975.

- ↑ Goddin 2008, p. 973.

- ↑ Farr 2007, p. 39.

- ↑ Peeters 1989, p. 148.

- ↑ Peeters 2012, p. 92.

- ↑ Apostolidès 2010, p. 9.

- ↑ Thompson 1991, p. 24.

- ↑ Apostolidès 2010, p. 10.

- ↑ Farr 2001, p. 12.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, p. 26; Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 24.

- ↑ Farr 2001, p. 35; Peeters 2012, p. 56.

- ↑ 110.0 110.1 Farr 2001, p. 29.

- ↑ McCarthy 2006, p. 38.

- ↑ Peeters 2012, pp. 76–77, 82.

- ↑ Goddin 2008, p. 148.

- ↑ Peeters 2012, p. 89.

- ↑ McCarthy 2006, p. 37.

- ↑ Thompson 1991, p. 40.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, p. 28.

- ↑ Cendrowicz 2010.

- ↑ Thompson 1991, pp. 62–63.

- ↑ Assouline 2009, p. 42; Peeters 2012, p. 64–65.

- ↑ Peeters 2012, p. 56.

- ↑ Thompson 1991, p. 62; Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 35; Peeters 2012, p. 77.

- ↑ Peeters 2012, p. 46.

- ↑ 124.0 124.1 Smith 2010.

- ↑ "History of the Lucca festival". 1972. Retrieved 15 July 2006.

- ↑ Index Translationum French top 10

Bibliography

- Apostolidès, Jean-Marie (2010). The Metamorphoses of Tintin, or Tintin for Adults. translated by Jocelyn Hoy. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-6031-7.

- Assouline (2009). Hergé, the Man Who Created Tintin. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-539759-8.

- Cendrowicz, Leo (4 May 2010). "Tintin: Heroic Boy Reporter or Sinister Racist?". TIME (New York City). Archived from the original on 6 June 2013. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- Farr, Michael (2001). Tintin: The Complete Companion. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-5522-0.

- Farr, Michael (2007). The Adventures of Hergé, Creator of Tintin. San Francisco: Last Gasp. ISBN 978-0-86719-679-5.

- Frey, Hugo (2008). "Trapped in the Past: Anti-Semitism in Hergé's Flight 714". In McKinney, Mark. History and Politics in French-Language Comics and Graphic Novels. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 9781604737615.

- Goddin, Philippe (2008). The Art of Hergé, Inventor of Tintin: Volume I, 1907–1937. San Francisco: Last Gasp. ISBN 978-0-86719-706-8.

- Hergé (1999) [1930]. Tintin in the Land of the Soviets. London: Methuen Children's Books. ISBN 978-0-416-19765-5.

- Lofficier, Jean-Marc; Lofficier, Randy (2002). The Pocket Essential Tintin. Harpenden, Hertfordshire: Pocket Essentials. ISBN 978-1-904048-17-6.

- McCarthy, Tom (2006). Tintin and the Secret of Literature. London: Granta. ISBN 978-1-86207-831-4.

- Peeters, Benoît (1989). Tintin and the World of Hergé. London: Methuen Children's Books. ISBN 978-0-416-14882-4.

- Peeters, Benoît (2012) [2002]. Hergé: Son of Tintin. Tina A. Kover (translator). Baltimore, Maryland: John Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-0454-7.

- Smith, Neil (28 April 2010). "Race row continues to dog Tintin's footsteps". BBC News. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- Theobald, John (2004). The Media and the Making of History. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-3822-3.

- Thompson, Harry (1991). Tintin: Hergé and his Creation. London: Hodder and Stoughton. ISBN 978-0-340-52393-3.

- Valla, Jean-Claude (May–June 2009). "La Belgique de la Jeune Europe". Nouvelle Revue d'Histoire (42): 55.

- Tayler, Christopher (7 June 2012). "Haddock blows his top [A review of two Tintin books]". London Review of Books (lrb.co.uk). Retrieved 7 July 2013.

Further reading

- (French) "Spécial Hergé : Hergé et Tintin en Dates". L'Express. 15 December 2006.

- Moore, Charles (26 May 2007). "A Tribute to the Most Famous Belgian". The Daily Telegraph (UK).

- Goddin, Philippe (7 November 2007). "Hergé: Lignes de vie". Editions Moulinsart.

- Benoît-Jeannin, Maxime (7 January 2007). "Les guerres d'Hergé". Aden. ISBN 978-2-930402-23-9

- Farr, Michael (October 2007). The Adventures of Hergé. John Murray. ISBN 0-7195-6799-8.

- Pierre Sterckx (Textes) / André Soupart (Photos), Hergé. Collectionneur d'Art, Brussels/Belgium (Tournesol Conseils SA-Renaissance du Livre) 2006, 84 p. ISBN 2-87415-668-X

External links

- Hergé on Tintin.com official site

- Hergé biography on À la découverte de Tintin

- Hergé on Lambiek Comiclopedia

- Hergé – mini profile and time line on Tintinologist.org

- Hergé publications in Belgian Tintin and French Tintin BDoubliées (French)

|