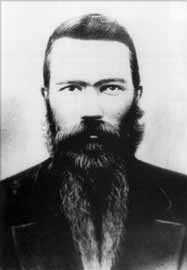

Henry Berry Lowrie

| Henry Berry Lowry | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

circa 1847 Robeson County, North Carolina, USA |

| Disappeared |

February 20, 1872 Robeson County, North Carolina |

Henry Berry Lowrie or "Lowry" (c. 1845 – February 20, 1872?) led a gang in North Carolina during and after the American Civil War. He is sometimes viewed as a Robin Hood type figure, especially by the Lumbee people, who consider him an ancestor and a pioneer in the fight for civil rights and tribal self-determination. Lowrie was described by George Alfred Townsend, a late 19th-century New York Herald correspondent, as “[o]ne of those remarkable executive spirits that arises now and then in a raw community without advantages other than those given by nature."[1]

Early life

Lowrie was born to Allen and Mary (Cumbo) Lowrie in the Hopewell Community, in Robeson County, North Carolina. His father owned a successful 350-acre (1.4 km2) mixed-use farm in Robeson County. Henry Lowrie was one of 12 children. In 1872, George Alfred Townsend said of him: "The color of his skin is of a whitish yellow sort, with an admixture of copper—such a skin as, for the nature of its components, is in color indescribable, there being no negro blood in it except that of a far remote generation of mulatto, and the Indian still apparent."[2]

Gang leader

Early in the Civil War, North Carolina turned to forced labor to construct her defenses. Several Lowrie cousins, excluded from military service because they were free men of color (also called free blacks), had been conscripted to help build Fort Fisher, near Wilmington, North Carolina. Other non-whites resorted to "lying out" or hiding in Robeson County's swamps to avoid being rounded up by the Home Guard and forced to work for low wages.

On December 21, 1864, James P. Barnes, a neighbor of Allen Lowrie, accused him of stealing hogs. Henry Lowrie killed Barnes. Lowrie also killed James Brantley Harris, a conscription officer, in January 1865 for allegedly mistreating the Lowrie family's women. In March 1865, the Home Guard searched Allen Lowrie's home and found firearms, which he was forbidden as a free person of color to own. The Home Guard convened a kangaroo court, convicted Allen Lowrie and his son William, and executed them. Henry Lowrie reportedly was watching from the bushes.

A gang led by Henry Lowrie committed a series of robberies and murders, continuing until 1872. The attempts to capture the gang members became known as the Lowry War. The Lowrie gang consisted of Henry Lowrie, his brothers Stephen and Thomas, two cousins (Calvin and Henderson Oxendine), two of his brothers-in-law, two black men who were escaped slaves, a white man, and two other men of unknown relation.[3][4]

Lowrie's gang continued its actions into Reconstruction. Republican governor William Woods Holden outlawed Lowrie and his men in 1869, and offered a $12,000 reward for their capture: dead or alive. Lowrie responded with more revenge killings.[2] On December 7, 1865, he married Rhoda Strong. Arrested at his wedding, Lowrie escaped from jail by filing his way through the jail's bars.[4]

Lowrie's band opposed the postwar conservative Democratic power structure, which was pro-white supremacy. The Lowrie gang robbed and killed numerous people of the establishment. Because of this, they gained the sympathy of the non-white population of Robeson County. The authorities were unable to stop the Lowrie gang, largely because of this support.

In February 1872, shortly after a raid in which he robbed the local sheriff's safe of more than $28,000, Henry Berry Lowrie disappeared. It is claimed he accidentally shot himself while cleaning his double barrel shotgun.[5] As with many folk heroes, the death of Lowrie was disputed, and he was reportedly seen at a funeral several years later.[4] Without his leadership, every member except two were subsequently captured or killed.

Legend and significance

Starting in 1976, Lowrie's legend has been presented each summer in an outdoor drama called Strike at the Wind!.[6] Set during the Civil War and Reconstruction years, the play portrays Lowrie as an Indian culture hero who flouts the white power structure by fighting for his people and defending the county's downtrodden citizens.

References

- ↑ Townsend, George Alfred (1872). The Swamp Outlaws: or, The North Carolina Bandits; Being a Complete History of the Modern Rob Roys and Robin Hoods, New York: Robert M. DeWitt.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Henry Berry Lowrie & The Lumbee: story, pictures and information". Fold3. October 17, 2008. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

- ↑ "Henry Berry Lowrie". Lumbee Regional Development Association. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Currie, Jefferson. "Henry Berry Lowry Lives Forever". North Carolina Museum of History. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

- ↑ "LUMBEE-L Archives: Henry Berry Lowry and the Physician who pronounced him dead". RootsWeb. November 9, 2007. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

- ↑ "Strikeatthewind.com". 2006. Retrieved March 26, 2006.

Newspapers

- "A Notorious Desperado Killed in North Carolina—-A Company of Soldiers After his Confederates—A Defaulting Book-keeper in Chicago." New York Times December 18, 1870, p. 1.

- "Are the Robeson County, N.C., Outlaws KuKlux?" New York Times May 16, 1871, p. 1.

- "Robin Hood Come Again." New York Times 22 July 1871: p. 4, col. 5.

- "The North Carolina Outlaws—-Lowrey and his Gang—-The Authorities Defied—-Pursuit by the Soldiers." New York Times October 11, 1871, p. 11.

- "A new expedition: Proposition to Capture the Lowery Gang of Outlaws–-Singular Enterprise of a Fourth Ward Character." New York Times 18 March 1872: p. 5, col. 3.

- "The North Carolina Bandits." Harper’s Weekly 16 (30 March 1872): pp. 249, 251-2.

- "The Lowrey Outlaws: Particulars of the Murder of Col. F. M. Wishart in Robeson County, North Carolina—a Base and Treacherous Assassination." New York Times May 8, 1872, p. 3.

- "The Lowery Gang." New York Times 4 May 1874: p. 2, col. 3.

Selected primary sources

- "Criminal Action Papers Concerning Henry Berry Lowry." MS. North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh, NC. 1 box.

- Gorman, John C. “Henry Berry Lowry paper.” Unpublished manuscript. c. 1875? Housed in the North Carolina Division of Archives and History, Raleigh, N.C. 26p.

- "A History of the Capture of the Notorious Outlaw George Applewhite, alias, Ranse Lowery, of the Lowery Gang of Outlaws, or Robeson County, N.C. .. ." Columbus, GA: Thos. Gilbert, 1872.

- Norment, Mary C. The Lowrie History, As Acted in Part by Henry Berry Lowrie, the Great North Carolina Bandit. With Biographical Sketches of His Associates. Being a Complete History of the Modern Robber Band in the County of Robeson and State of North Carolina. Wilmington: Daily Journal Printer, 1875.

- Townsend, George Alfred. The Swamp Outlaws: or, The North Carolina Bandits; Being a Complete History of the Modern Rob Roys and Robin Hoods. The Red Wolf Series. New York: Robert M. DeWitt, 1872.

- "U.S. Cong. Joint Select Comm. to Inquire into the Condition of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary States. Report… on the Condition of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary States. Made to the Two Houses of Congress", 19 February 1872. 42nd Cong., 2nd Sess. Report No. 41, Part 1. 1872. Rpt. New York: AMS, 1968. See Vol. 2, pp. 283–304.

Secondary sources

- Barton, Garry Lewis. The Life and Times of Henry Berry Lowry. Pembroke, NC: Lumbee Publishing Co., 1979 1992.

- Cassia, Paul Sant. "Banditry, Myth, and Terror in Cyprus and Other Mediterranean Societies." Comparative Studies in Society and History 35, no. 4 (October 1993).

- Evans, W. McKee. To Die Game: the Story of the Lowry Band, Indian Guerillas of Reconstruction. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1971.

- ______. "Henry Berry Lowry." In Dictionary of North Carolina Biography, ed. William S. Powell. Vol. 4. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991, 104-05.

- Hauptman, Lawrence M. "River Pilots and Swamp Guerillas: Pamunkee and Lumbee Unionists.” In Between Two Fires: American Indians in the Civil War. New York: Free Press, 1995, 65-85.

- Hobsbawm, Eric. Bandits. New York: Delacorte Press, 1969.

- Manning, Charles. "Last of Lowerys Recalls Saga of Death and Terror." Greensboro Daily News 19 January 1958: A13.

- Rockwell, Paul A. “Lumbees Rebelled Against Proposed Draft by South." Asheville Citizen-Times 2 February 1958.

- Wilkins, David E. “Henry Berry Lowry: Champion of the Dispossessed." Race, Gender & Class 13.2 (Winter 1996): 97-111.

- William McKee Evans, "To Die Game: The Story of the Lowry Band, Indian Guerrillas of Reconstruction", Syracuse University Press, 1995

- Adolph L. Dial, David K. Eliades, "The Only Land I Know: A History of the Lumbee Indians", Syracuse University Press, 1996

- Karen I. Blu, "The Lumbee Problem: The Making of an American Indian", University of Nebraska Press, 2001

- E. Stanly Godbold, Jr. and Mattie U. Russell, "Confederate Colonel And Cherokee Chief: The Life Of William Holland Thomas", University of Tennessee Press, 1990

Henry Berry was an owner of an extremely large number of acres in Marion County, South Carolina and is said by local legend to be the biological father of Henry Berry Lowrie.

External links

|