Henriette Caillaux

| Henriette Caillaux | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Henriette Raynouard December 5, 1874 Rueil-Malmaison |

| Died | January 29, 1943 (aged 68) |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | Socialite, Art Historian |

| Known for | Killing the newspaper editor, Gaston Calmette |

| Spouse(s) |

|

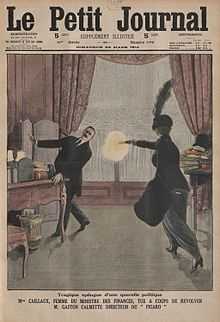

Henriette Caillaux (5 Dec 1874 – 29 Jan 1943) was a Parisian socialite and second wife of the former Prime Minister of France. On March 16, 1914, she shot and killed Gaston Calmette, editor of the newspaper Le Figaro.

Early life and marriages

Henriette Caillaux was born Henriette Raynouard, at Rueil-Malmaison on 5 December 1874.[1] At the age of 19, she married Léo Claretie, a writer twelve years her senior.[2] They had two children. In 1907 she began having an affair with Joseph Caillaux while both he and she were still married. In 1908, she divorced Léo; Caillaux had more difficulties in divorcing his wife, but he eventually did so and they married in October 1911.[2] Their joint assets were worth around 1.5 million francs, placing them amongst France's wealthiest couples.[2]

While serving as Minister of Finance in the government of France, Joseph Caillaux came under bitter attack from his political foes. At a time when newspapers took political sides, the editor of the Le Figaro newspaper, Gaston Calmette, had been a severe critic. Gaston Calmette received a letter belonging to Joseph Caillaux that journalistic etiquette at the time dictated should not be published. The letter seemed to suggest that improprieties had been committed by Caillaux – in it he appeared to admit having orchestrated the rejection of a tax bill while publicly pretending to support its passage. Gaston Calmette published the letter at a time when Joseph Caillaux, in his capacity as Minister of Finance, was trying to get a progressive taxation law passed by the French Senate. The publication of his letter severely tarnished Caillaux's reputation and caused a great political upheaval.

Shooting of Gaston Calmette

Henriette Caillaux believed that Calmette would further publish private letters that would demonstrate that Caillaux and she had intimate relationships whilst he was still married to his first wife. She felt the only way for her husband to defend his reputation would be to challenge Calmette to a duel, which, one way or another, would destroy her and her husband's life. Madame Caillaux made the decision to protect her beloved husband by sacrificing herself.

At 5pm on 16 March 1914, she entered offices of Le Figaro, wearing a fur coat and with her hands in a fur muff,[3] and asked to see Gaston Calmette. When told he was away but would return within an hour, she sat to wait.[4] Calmette returned at 6pm with his friend, the novelist Paul Bourget and agreed to briefly see Madame Caillaux, to Bourget's surprise.[4]

After being shown into Calmette's office, Henriette Caillaux exchanged a few words with him, then pulled out a .32 Browning automatic pistol she had been concealing within the muff and shot him six times, four shots hit Calmette and he was critically wounded. [5] Henriette Caillaux made no attempt to escape and newspaper workers in adjoining offices quickly summoned a doctor and the police. She refused to be transported to the police headquarters in a police van, insisting on being driven there by her chauffeur in her own car, which was still parked outside. The police agreed to this and she was formally charged upon reaching the headquarters.[3] Gaston Calmette died six hours after being shot.[5]

Henriette Caillaux's trial dominated French public life. It featured a deposition from the president of the Republic, an unheard-of occurrence at a criminal proceeding almost anywhere, along with the fact that many of the participants were among the most powerful members of French society. At a time when feminism was still beginning to affect French society, most republican and socialist men paid no more than lip service to the feminist cause. However, it was this male chauvinism that actually proved Henriette Caillaux's best friend during the proceedings. She was defended by the prominent attorney Fernand Labori who convinced the jury that her crime, which she did not deny, was not a premeditated act but that her uncontrollable female emotions resulted in a crime of passion. The male belief that women were not as strong emotionally as men resulted in her acquittal on 28 July 1914.

Later life

In the early 1930s she was awarded a diploma of the École du Louvre for her thesis on the sculptor Jules Dalou. She published a reference book in 1935 in which she established an inventory of the work of this artist.[6] She died in 1943.

Legacy

In 1968 a German television film Madame Caillaux was made.

A 1985 made for French television film called L'Affaire Caillaux and a 1992 book titled Trial of Madame Caillaux by American history professor Edward Berenson recounts the event. In addition, Robert Delaunay used an illustration of the assassination as the basis for his 1914 painting Political Drama.[7]

References

- ↑ Acte de naissance nº 213, année 1874, état civil de Rueil

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Berenson (1992), p.13

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Berenson (1992), p.2

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Martin (1984), p.151

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Martin (1984), p.152

- ↑ Henriette Caillaux, Aimé-Jules Dalou, L'homme - L'œuvre, Paris, Delagrave, 1935

- ↑ I think I see... at the National Gallery of Art

Further reading

- Kershaw, Alister. Murder in France. (London: Constable, 1955), 90-117.

- Berenson, Edward. The Trial of Madame Caillaux (Univ of California Press: Oxford, 1992). ISBN 0-520-08428-4

- Martin, Benjamin F. (1984). The Hypocrisy of Justice in the Belle Epoque. Louisiana State University Press.

|