Hendrik van Rheede

Hendrik Adriaan van Rheede tot Drakenstein (Amsterdam, 13 April 1636 – at sea, 15 December 1691) was a military man and a colonial administrator of the Dutch East India Company and naturalist. Between 1670 and 1677 he served as a governor of Dutch Malabar and employed 25 people on his book "Hortus Malabaricus", describing 740 plants in the region.[1] The plant Entada rheedii is named for him.

Biography

Van Rheede was born in a family of noblemen that played a leading part in the political, administrative and cultural life of the province Utrecht. His mother Elisabeth van Utenhove died in 1637, his father, Ernst van Rheede, Council at the Admiralty of Amsterdam, died when he was four.[2][3] Hendrik Adriaan, the youngest of seven children, left home at the age of fourteen. In 1656 he joined as a soldier in the Dutch East India Company and met with Johan Bax van Herentals. Van Rheede served under Admiral Rijcklof van Goens in campaigns against the Portuguese on the west coast of India. He gained rapid promotion becoming an ensign. In 1663, during a siege of Cochin, he was ordered to arrest the queen there and this act saved her life from the massacre of the royal family. The subsequent king of Cochin maintained cordial relations with him and Van Rheede was the Dutch captain who mediated with the Kingdom of Cochin. In 1665 he was appointed as commander in Jaffna and had Johan Nieuhof locked up for smuggling pearls.[4]

In 1669 Van Rheede seems to have been forced to resign from the Dutch East India Company by Van Goens.[5] The resignation was made as he opposed the repressive measures of Van Goens and instead favoured negotiation, but in 1670 he is appointed as commander of Dutch Malabar. In 1671 he fought with the Zamorin of Calicut. In 1672 he had to deal with the former VOC-employee François Caron, then serving the French East India Company.

In 1677 Van Rheede moved to Jakarta, being appointed in the Counsel of India. He stayed for about six months but the conflict with Van Goens grew fiercer. He returned to Amsterdam in June 1678. Since 1680 he could call himself Lord of Mijdrecht. In 1681 he signed a contract with the botanists Jan Commelin and Johannes Munnicks [6] and worked on the manuscript.

In 1684 he was empowered by the "directors" (Council of Seventeen) of the Company to inspect the Cape Colony, Ceylon and Dutch India to combat corruption within their employees.[7] He appointed Isaac Soolmans to accompany him. They visited Simon van der Stel in Cape of Good Hope, and Groot Constantia; the area Groot Drakenstein was named after him.[8] Van Rheede recommended measures for forestry and viniculture.[9] In 1687 Governor Van der Stel opened this region to farmers.[10] Van Rheede was a bachelor, but had adopted a girl from Malabar with an unknown Dutch father.[11] He met with Van Goens junior, an ambitious administrator on his way to Batavia. Both men didn't like each other at all. Some time before Van Goens had given orders—afraid for competition anywhere else in the world—to extirpate all the acclimatizating cinnamon trees which were destined for the Amsterdam Municipal Garden. It is possible that the rare trees for the Grand Pensionary Gaspar Fagel were then also destroyed.[12]

Van Rheede sailed to Colombo and after two months to Bengal. He visited many VOC trading posts, especially around Hooghly. His next destination was the Coromandel and he stayed for one year in Nagapattinam. In 1690 he founded a seminary in Jaffna. Then he went to Tuticorin and the Malabar. In the end of November 1691 he sailed to Dutch Suratte, but died at sea, off the coast of Bombay on December 15, 1691. Some authors suggest that he was poisoned by VOC employees.[13] others that he was sick already for a while.[14] He was buried at Surat on 3 January 1692 in the presence of his daughter Francine.[15]

Work in natural history

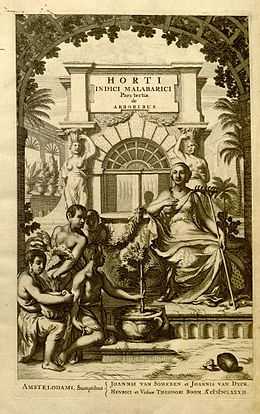

His work on the plants of the Malabar region had begun earlier in 1674 and it was around 1675 that the draft of the first volume was produced. [citation needed] Since 1660 the Company encouraged publication of scientific work; the documentation of the useful plants by Van Rheede would help in the fight against local diseases. The first volume of the Hortus Malabaricus, published in 1678, a compendium of the plants of economic and medical value in the south Indian Malabar region, was undertaken when Jonkheer van Rheede was the Dutch Governor of Cochin and continued for the next three decades. It was published in twelve volumes and in four languages: Latin, Sanskrit, Arabic and Mayalam.[16] Mentioned in these volumes are plants of the Malabar region which in his time referred to the stretch along the Western Ghats from Goa to Kanyakumari. The ethno-medical information presented in the work was extracted from palm leaf manuscripts by a famous practitioner of herbal medicine named Itty Achuden. The compilations were edited by a team of nearly a hundred [17] including physicians, professors of medicine and botany, amateur botanists (such as professor Arnold Seyn, Theodore Jansson of Almeloveen, Paul Hermann, Johannes Munnicks, Jan Commelin, Abraham Poot, the translator of a Dutch version), Indian scholars and vaidyas (physicians) of Malabar and adjacent regions, and technicians, illustrators and engravers, together with the collaboration of company officials, clergymen (Johannes Casearius and Father Mathew of St. Joseph). He was also assisted by the King of Cochin and the ruling Zamorin of Calicut.[18]

Carolus Linnaeus made use of Rheede's work,[16] noting in the preface of his Genera Plantarum (1737) that he did not trust any authors except Dillen in Hortus Elthamensis, Rheede in Hortus Malabaricus and Charles Plumier on American plants and further noted that Rheede was the most accurate of the three.[19]

References

- ↑ The Cambridge History of Science: Early modern science By Roy Porter, Katharine Park, Lorraine Daston

- ↑ http://www.inghist.nl/retroboeken/nnbw/#source=3&page=512

- ↑ http://www.worldroots.com/foundation/european/widdekindesc.htm

- ↑ Heniger, J. (1986) Hendrik Adriaan van Reede tot Drakenstein (1636–1691) and Hortus Malabaricus – A contribution to the history of Dutch colonial botany, p. 22.

- ↑ H.Y. Mohan Ram (2005) On the English edition of Van Rheede’s Hortus Malabaricus by K. S. Manilal(2003). Current Science, Bangalore, India 89(10)

- ↑ http://indianmedicine.eldoc.ub.rug.nl/root/H/40628/

- ↑ Adams, Julia (1996). "Principal and Agents, Colonialists and Company Men: The decay of Colonial Control in the Dutch East Indies". American Sociological Review 61 (1): 12–28.

- ↑ A DIFFERENT HISTORY OF FRANSCHOEK and the DRAKENSTEIN DISTRICT

- ↑ New Scientist 25 Jun 1987

- ↑ Intro (English) to the Resolutions of Cape of Good Hope / Places named after members of the Council of Policy

- ↑ Heniger, J. (1986) Hendrik Adriaan van Reede tot Drakenstein (1636–1691) and Hortus Malabaricus – A contribution to the history of Dutch colonial botany, p. 87, 90.

- ↑ Heniger, J. (1986) Hendrik Adriaan van Reede tot Drakenstein (1636–1691) and Hortus Malabaricus – A contribution to the history of Dutch colonial botany, p. 72

- ↑ http://www.inghist.nl/retroboeken/nnbw/#source=3&page=513

- ↑ Heniger, J. (1986) Hendrik Adriaan van Reede tot Drakenstein (1636–1691) and Hortus Malabaricus – A contribution to the history of Dutch colonial botany, p. 81.

- ↑ Drawing of the funeral procession of Esquire van Rheede

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Fournier M. (1987). "Enterprise in botany: Van Reede and his Hortus malabaricus – Part l.". Archives of Natural History 14 (2): 123–58.

- ↑ http://www.lib.uchicago.edu/e/su/southasia/lach.html

- ↑ H.Y.Mohan Ram (2005) On the English edition of Van Rheede’s Hortus Malabaricus by K. S. Manilal(2003). Current Science, Bangalore, India 89(10)

- ↑ Mueller-Wille, S & K. Reeds (2007). Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 38. pp. 563–572. doi:10.1016/j.shpsc.2007.06.003.

- ↑ "Author Query for 'Rheede'". International Plant Names Index.

|