Hendrick Jacobs Falkenberg

| Hendrick Jacobs Falkenberg | |

|---|---|

| Born |

c. 1640 Holstein, Germany |

| Died |

c. 1712 Little Egg Harbor Township, Burlington County, New Jersey |

| Other names |

Hendrick Jacobs Henry Jacobs |

| Occupation | linguist, interpreter |

| Religion | Swedish Lutheran, Quaker |

| Spouse(s) |

(1) __________ Sennicksdotter (a daughter of Sennick Broer) (2) Mary Jacobs |

| Children |

by first wife:

by second wife:

|

Hendrick Jacobs Falkenberg (pronounced "Falkenberry" in Swedish) (c. 1640 – c. 1712), also known as Hendrick Jacobs or Henry Jacobs, was an early American settler along the Delaware River, and was considered to be the foremost language interpreter for the purchase of Indian lands in southern New Jersey. He was a linguist, fluent in the language of the Lenape native Americans, and in early histories of New Jersey he is noted for his service to both the Indians and the English Quakers, helping them negotiate land transactions. Though he was from Holstein, now a part of Germany, he was closely associated with the Swedes along the Delaware because his wife was a Finn and a member of that community.

In 1671 Falkenberg lived on property belonging to his father-in-law, Sennick Broer, on the Christina River, now in Wilmington, Delaware. He later moved to the vicinity of Burlington, New Jersey where he lived for nearly two decades, and where he was visited by two journalists of the Labadist sect who were looking for a place to establish a new community. The journalists provided the only known record of Falkenberg's place of origin, and also described his dwelling place, a Swedish style log cabin. By 1693 he had moved from the Delaware River across the Province of New Jersey to become the first European settler in Little Egg Harbor Township, New Jersey, near Tuckerton. Here he dug a cave for a home, but later built a large house made of clapboard where he lived until his death, sometime after 1711. Falkenberg wrote a will in 1710, but for unknown reasons it was not probated until thirty-three years later. While he had only two known children to reach adulthood, each by a different wife, he has a large progeny as the ancestor of the Falkinburg family of New Jersey and the Fortenberry and Faulkenberry families of the southern United States.

Delaware River

Hendrick Jacobs Falkenberg was born roughly 1640 and came from Holstein, which is currently a part of Schleswig-Holstein, the northernmost federal state of Germany bordering on Denmark.[1] He likely came to the Delaware River between 1655 and 1664, during the rule of the Dutch who brought many Holsteiners from Europe on Dutch ships.[2] Naming of individuals at this time used the patronymic system, where a child had a given name followed by the name of the father. Thus his name was Hendrick, or Henry, the son of Jacob. However, also living along the Delaware at the time was another Hendrick Jacobs. Perhaps for this reason, the subject Hendrick Jacobs eventually adopted the surname Falkenberg (with numerous spelling variations)[a] and the other Hendrick Jacobs adopted the surname Hendrickson.[2] In this article the subject will be called either Hendrick Jacobs or Hendrick Jacobs Falkenberg (with many variations), depending on what he is called in the source document.

Service as interpreter

In colonial records of New Jersey the name of Hendrick Jacobs Falkenberg occurs frequently in land transactions where he acted as interpreter between the native Lenape Indians and European settlers.[3] The Indians were eager to acquire European-made goods and the Europeans were eager to acquire land, so the service of Falkenberg was sought by both parties. In his book on the Indians of New Jersey, Frank Stewart considered Falkenberg to be the foremost interpreter in the purchase of Indian lands in southern New Jersey, a sentiment echoed by Dr. Peter Craig in his book about the inhabitants along the Delaware.[3][4] Falkenberg was particularly helpful to the English Quakers moving into the area of the Delaware River in the late 1670s, helping them negotiate land transactions with the Indians. When he was evicted from one of his properties in 1678, these Quakers came to his defense and petitioned the Governor of New York on his behalf.[5][6] For his services as interpreter, the Indians gave him an 800-acre tract of land in Little Egg Harbor Township in 1674, and the English gave him a 200-acre parcel of land on Rancocas Creek in Burlington County in 1682.[7]

Falkenberg's usefulness as an interpreter went beyond the conduct of land transactions, an example of which occurred in 1681 when the Lenape Indian King Ockanickon was dying. The King gave his final words to his nephew, Jahkursoe, whom he appointed to be his successor as King, but he also wanted to share his words with his gathered friends and family, both Indian and Christian. Falkenberg interpreted the short statement and then a witnessing Englishman by the name of John Cripps wrote the statement and sent it in a letter to a friend in London where it was put into print. In this small printed document, Falkenberg's name appears as the translator and is written "Henry Jacobs Falckinburg." This is the first known instance where his name is given with the surname included.[8] Subsequently his name appears both with and without the surname in various printed records.

First residence: Deer Point

The first public record found for the subject was a deed dated October 12, 1672, when he was named as an heir of "Seneca Brewer" (Sennick Broer), being called "Henrickus Jackson" in that document.[2] This indicates that the wife of Hendrick Jacobs was a daughter of the Finn, Sennick Broer, but her given name has not been found. Sennick Broer and family arrived in the Delaware River area on the ship Mercurius in 1656, just after the Dutch took control of New Sweden. The Dutch attempted to turn the ship around and send the passengers back to Sweden, but with the help of some Lenape Indians the vessel was able to slip into port and offload its passengers consisting of 92 Finns and 13 Swedes.[2] Because his wife was of the Swedish colony along the Delaware, Hendrick Jacobs was also considered a member of the Swedish settlement.

In 1671, when the English made a census of the inhabitants of the Delaware River, Hendrick Jacobs was likely living with his wife and brothers-in-law on property belonging to his father-in-law, Sennick Broer. This 900-acre tract was called "Deer Point" and located on the north side of the Christina River, later a part of Wilmington, Delaware.[4] The length of his stay at Deer Point isn't known, but by 1674 Jacobs was living 44 miles to the northeast, upstream along the Delaware River on an island called Mattiniconck (or Matinicum), adjacent to the town of Burlington, New Jersey.

Matiniconck Island

In August 1674 Hendrick Jacobs (later Falkenberg) was a party to a deed stating that his residence at the time was Matiniconck Island, a 300-acre island in the Delaware River opposite Burlington, New Jersey.[9][10] He shared ownership of the island, later called Burlington Island, with a Frenchman named Peter Jegou, with whom he had a long and fairly close relationship. In a court held at Newcastle, Delaware in May 1675, Jacobs petitioned against Jegou concerning a bargain for a still,[11] but thereafter, the relationship between the two men was much more amicable. Jegou was an attorney for Hendrick Jacobs in a November 1676 Newcastle court case, [12][13]and three years later in a case where Jegou was a plaintiff, Jacobs was called his friend.[14][b] Jacobs lived on Mattiniconck at least until late 1677 when a list of "Tydable Persons" of the Upland Court dated November 13, 1677, included "Hend: Jacobs upon ye Isld."[15][16][c]

Several years after 1664 when the English took control of the Delaware River, Robert Stacy, one of the Yorkshire commissioners of the Burlington Colony, obtained a lease for this island from Governor Edmund Andros of New York. Stacy tried to evict Jacobs and Jegou from the island and take possession of it in November 1678.[17][18] However, the following month twenty-nine Quaker residents of Burlington petitioned the Governor on behalf of Jacobs who had been of great service to them in getting land from the Indians, acting as interpreter of the native language.[5][6] While the immediate outcome of the litigation is not known, ultimately the West Jersey assembly passed an act in 1682 vesting possession of the island in the town of Burlington with rents to be used for school maintenance and education of youth.[19] Stacy did help compensate Jacobs, however, by approving a deed in January 1681/82 whereby Henry Jacobs was given 200 acres of land on the south side of Rancocas Creek, south of Burlington, in consideration for his services as an interpreter.[7] Jacobs likely resided at this location because on August 8, 1685, he sold this property, with dwelling house, to Noel Mew of Rhode Island.[20]

Lazy Point: Visit by journalists Danckaerts and Sluyter

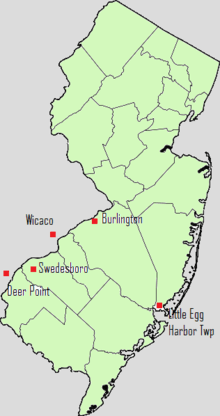

While Mattiniconck Island was called Hendrick Jacobs' residence in at least two documents, it is uncertain how long he lived there. By 1679 he was residing at a place called Lazy Point which he either owned in partnership with Peter Jegou, or leased from Jegou.[2] Jegou had bought this property in 1668 and was running an inn there in 1670 when he was plundered by the Indians, subsequently leaving the area for Deer Point on the Christina River.[4] A map copied by Jasper Danckaerts, probably from one made by an English surveyor the preceding year, shows this property of Hendrick Jacobs as being on the shore of the Delaware River across a small branch (Assiscunk Creek) from the town of Burlington, New Jersey. An engraving of this map is found in Woodward's history of Burlington County, New Jersey, with a modern version depicted in this article.[21] In 1679 Danckaerts and his partner Peter Sluyter, two envoys of the Labadist religious sect, came from the Netherlands to America to find a location to establish a community, their journey extending from New York southward to Maryland. On Saturday, November 18, 1679, (8 November, old style) the two journalists, along with their local guide named Ephraim, met with Hendrick Jacobs, stayed at his house, and wrote about the visit:

Before arriving at this village [Burlington], we stopped at the house of one Jacob Hendrix, from Holstein, living on this side. He was an acquaintance of Ephraim who would have gone there to lodge, but he was not at home. We, therefore, rowed on to the village, in search of lodgings, for it had been dark all of an hour or more; but proceeding a little further, we met this Jacob Hendrix, in a canoe with hay. As we were now at the village, we went up to the tavern, but there were no lodgings to be obtained there, whereupon we reembarked in the boat, and rowed back to Jacob Hendrix's, who received us very kindly, and entertained us according to his ability. The house, although not much larger than where we were the last night, was somewhat better and tighter, being made according to the Swedish mode, and as they usually build their houses here, which are block-houses, being nothing else than entire trees, split through the middle, or squared out of the rough, and placed in the form of a square, upon each other, as high as they wish to have the house; the ends of these timbers are let into each other, about a foot from the ends, half of one into half of the other. The whole structure is thus made, without a nail or a spike. The ceiling and roof do not exhibit much finer work, except among the most careful people, who have the ceiling planked and a glass window. The doors are wide enough, but very low, so that you have to stoop in entering. These houses are quite tight and warm; but the chimney is placed in a corner.[1]In his journal, Danckaerts called Hendrick Jacobs "Jacob Hendrix from Holstein," getting his name backwards, but providing the only reference to his place of nativity. The journal entry also provides a detailed description of an important Swedish contribution to American culture—the log cabin.

In 1684 and 1685 Hendrick Jacobs appears several times in the Burlington Court Records. In one case he was the defendant in an action of debt, and in another case he and several others were accused of stealing goods from a ship that ran ashore and was grounded.[22] He continued to live near the Delaware River at least until February 1688/89 when he was listed as a member of the Swede's Church in Wicaco (later in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania).[4] On January 26, 1691/92, he witnessed the will of Gilbert Morrell of Steatley, Burlington County, New Jersey, his name then being recorded as "Hinrich Jacobsen Falckenberg."[23]

Across the Province to Little Egg Harbor Township

Sometime in the early 1690s Falkenberg moved across the New Jersey colony to the area of Little Egg Harbor Township near the Atlantic Ocean, about 20 miles northeast of present-day Atlantic City, New Jersey, settling on land that he had acquired from the Indians in 1674. He was probably there by 1693 when he is absent from the census taken that year of the Swedes along the Delaware River.[2] On April 11, 1697, a deed was drafted confirming the 1674 offering by Indians of land at Little Egg Harbor, his name being recorded in the 1697 document as "Henery Jacobs Faukinburge."[9][10] On February 7, 1698/99, Falkenberg had the 800 acre tract of land surveyed, 200 acres of which encompassed the two islands of Monhunk (later Osborn's Island) and Minicunk (later Wills' Island).[24][25] These islands are at the north end of Little Egg Harbor, but they have been absorbed by the mainland and are scarcely distinguishable as islands.

Leah Blackman, in her history of Little Egg Harbor Township, relates that according to tradition the subject was the first white man to settle in Little Egg Harbor Township.[26] Once arriving in this area he dug a cave in a steep hill on the eastern side of a little stream on the portion of the tract later known as the Joseph Parker farm; the remains of the cave were still discernable as an indentation in the ground as late as 1850.[27][28] Falkenberg sustained himself and his family as a hunter, fowler, fisherman and oysterman.[28] It is likely that his first wife had died prior to his move to the ocean side of the colony, but he may have brought his son Henry, who was likely a teenager at the time. Blackman relates that as a widower he was not interested in housekeeping, so made a journey to Swedesboro, New Jersey to find a wife. Being successful, he brought his bride-to-be back to his cave home and prepared a large wedding, inviting his Indian friends, and being married according to the Friends' (Quaker) tradition.[29] This likely took place in 1697 or 1698, since the first child of this marriage was born in early 1699.[30]

Falkenberg's new wife, called Mary Jacobs (maiden name not known), became a member of the local Friends' Meeting, as did Falkenberg.[31] Blackman writes that Mary Jacobs was a female minister of the congregation who probably spoke at the first meeting held in the new congregation house built in 1709.[32] For about seventy years after the settlement of Little Egg Harbor, the Friends were the only religious denomination in the township and their meeting house is where most who lived in the area worshipped.[31] Mary continued to appear in various Friends' records after 1709 and was still living on the "10th day of the 8th month 1728" (October 10, 1728) when she and Ann Ridgaway brought a certificate upon their return from Long Island, as recorded in the Little Egg Harbor Monthly Meeting minutes.[33]

End of life

Blackman relates that when Falkenberg left his cave home, "he moved into a commodious clap-boarded mansion that he had built on his farm, and in this house it is probable he died."[34] This farm and house stayed in the family until 1785 when it was sold to Henry Willits by the subject's grandson, John Falkinburg.[35] The last public record found for Hendrick Jacobs Falkenberg was dated October 1, 1711, when he bought land at Little Egg Harbor from John Cooke.[36] He wrote his will in June 1710, naming wife Mary as sole executrix with friends Edward Andrews and John Wills to assist her, and mentioning only one child, Jacob, a minor.[37] John Woolman, George Bliss and John Wills were witnesses. For unknown reasons, the instrument wasn't presented for probate until thirty-three years after its writing, on June 7, 1743, long after Falkenberg's death, when John Wills appeared in court as the only surviving witness.[37] Though Mary was living in 1728, she had likely died by the time the will was presented in 1743, as she does not appear in any probate documents. Falkenberg likely died shortly after the writing of the will as his name does not appear on any records after 1711.[2]

Summary of where Falkenberg lived

The following summary pinpoints the known residences of Hendrick Jacobs Falkenberg while he lived in America, giving approximate dates for each.

- 1671-1672 Deer Point on the Christina River (later in Wilmington, Delaware)

- 1674-1678 Mattiniconck Island, in the Delaware River adjacent to Burlington, New Jersey

- 1678-1682 Lazy Point, across Assiscunk Creek from Burlington, New Jersey

- 1682-1685 Rancocas Creek, south of Burlington, New Jersey

- 1685-c.1692 unknown, but he was a member of the Swedish Church at Wicaco (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) in February 1688/89[4]

- c.1692-c.1712 Little Egg Harbor Township, near Tuckerton, New Jersey

Family

Children

Only three children of Hendrick Jacobs Falkenberg are known, one by his first wife and the other two by his second.

By his first wife:

- Henry Falkenberg/Faulkenberry/Fortenberry, born roughly 1680, went to Bladen County, North Carolina by way of Cecil County, Maryland and Orange County, Virginia; he was still living in 1759.[38] His name would have been Hendrick Hendricks Falkenberg using the patronymic system, but he is never called this in any known public record. No record mentioning his name has been found along the Delaware River or anywhere in New Jersey. However, circumstantial evidence indicates that this Henry is the son of Hendrick Jacobs Falkenberg. First, the name Falkenberg is very rare in the American colonies in the 17th century, so a family connection is likely among those bearing the name, and Henry is the right age to be a son of Hendirck Jacobs. Secondly, there was a known connection between the Sennick Broer family and the Falkenberg/Faulkenberry/Fortenberry family in North Carolina. When Brewer Sinixsen, a great-grandson of Sennick Broer, died in North Carolina, the Falkenberg descendants claimed his land as their own, implying a close family connection.[39] This connection is that Henry Falkenberg, as a grandson of Sennick Broer, was a first cousin once removed of the Brewer Sinixsen who died in North Carolina.[2]

By his second wife:[30]

- Mary Falkenburg, born 10:11mo:1698 (January 10, 1698/99), was not mentioned in the will of her father, and may have died young.[37]

- Jacob Hendricks (or Jacob Henry) Falkenburg, born 14:6mo:1702 (August 14, 1702), was the only child named in his father's will. His name is given incorrectly by Blackman, who consistently calls him Henry Jacob Falkinburg Jr. This is erroneous; the Friends' records and every other public document bearing his name clearly call him Jacob Hendricks Falkenburg, in keeping with the patronymic tradition.[37] Jacob was married twice, with the name of his first wife unknown and his second wife being Penelope Stout, a descendant of the Penelope Stout who lived to be 111 years old.[40]

Descendants

The descendants of Hendrick Jacobs Falkenberg were true American pioneers. While most of the family of his younger son Jacob remained in New Jersey or adjacent states, his older son Henry initiated the spread of the family through every southern state from Virginia to Texas. Following is a list of descendants who were the first known members of the family to settle in the areas given:

- Jacob Faulkenberry (b. c. 1715) and John Faulkenberry (b. c. 1720), sons of Henry Falkenberg (b. c. 1680), went with their father to Orange County, Virginia and Bladen County (later Anson County), North Carolina. They subsequently went to Lancaster District, South Carolina.[41]

- David Faulkenberry (b. c. 1746) and Robert Faulkenberry (b. c. 1755), sons of the above Jacob (b. c. 1715), went to Jackson County, Georgia. David later moved to Rutherford County, Tennessee.[42]

- James Leath Fortenberry (c. 1755 - 1831) was undoubtedly a grandson of Henry Falkenberg (b. c. 1680), but by which son has not been determined. He was the founder of the family in Lawrence County, Arkansas, coming there by way of New Madrid County, Missouri Territory.[43] Some of his descendants later settled in the Texas counties of Denton, Hunt, Wise and Cooke. [44]

- Jacob Falconberry (b. 1757), the son of Isaac Faulkenberry (b. c. 1725) and grandson of Henry Falkenberg (b. c. 1680), went to Lincoln County, Kentucky and then to Jennings County, Indiana.[45]

- William Fortenberry (c. 1772 - February 5, 1842), the son of John Faulkenberry (b 1740) and grandson of Jacob Faulkenberry (b. c. 1715) mentioned above, was the founder of this family in Pike County, Mississippi.[46]

- Isaac Fortenberry (c. 1775 - November 1845), the son of Isaac Fortenberry (b. c. 1748) and grandson of the first mentioned John Faulkenberry (b. c. 1720), founded the Fortenberry family in Marion County, Mississippi.[47]

- Israel Falkenberry (1781 - 1861), the brother of the preceding William Fortenberry, settled in Monroe County, Alabama.[48]

- Joseph Fortenberry (1817 - 1856), the son of Jacob Fortenberry (1789 - 1862) and grandson of James Leath Fortenberry, above, settled in Hunt County, Texas about 1850.[49]

- Oliver Rice Fortenberry (1821 - 1874), William M. Fortenberry (1827 - 1884), and A. H. Sevier Fortenberry (1828 - 1868), all brothers of the preceding Joseph Fortenberry (1817-1856), settled in Denton County, Texas between 1850 and 1869.[50]

Notable descendant

U.S. President Jimmy Carter is descended from Mary Margaret Fortenberry (or Falkenborough) who married George Helms and lived in North Carolina in the mid-1700s. Mary Fortenberry was likely a daughter or granddaughter of Henry Falkenberg, oldest son of Hendrick Jacobs Falkenberg.[51][52]

See also

- Colonial history of New Jersey

- Little Egg Harbor Township

- Province of New Jersey

- Tuckerton, New Jersey

References

Notes

a. ^ The predominant spelling of the name in New Jersey became Falkinburg and in the southern states became Fortenberry, with Faulkenberry being another common variation.[53][54][55][56]

b. ^ Peter Jegou lived at Deer Point until 1683 and then moved to Cecil County, Maryland where his will was proved on April 1, 1687, mentioning no descendants.[4]

c. ^ The Upland Court was established by the Dutch in 1672, and had jurisdiction over the area on the west side of the Delaware River which later became the Province of Pennsylvania.

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Danckaerts, pp. 97-99.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Craig 2002.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Stewart, pp. 68-70, 79-80.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Craig 1999, pp. 71-72.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Gehring, p. 231.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Whitehead, pp. 287-288.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Colony of New Jersey Archives, p. 21:396.

- ↑ Cripps 1682.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Colony of New Jersey Archives, p. 21:513.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Stewart 1932, pp. 79-80.

- ↑ Gehring, p. 74.

- ↑ Ricord 1886, p. 516.

- ↑ Colonial Society of Pennsylvania 1904, p. 12.

- ↑ Armstrong, pp. 140-142.

- ↑ Armstrong, p. 78.

- ↑ Cook 1938, p. 4.

- ↑ Gehring, pp. 229-230.

- ↑ Whitehead, pp. 286-287.

- ↑ Barber and Howe, p. 88.

- ↑ Colony of New Jersey Archives, p. 21:414.

- ↑ Woodward 1880.

- ↑ Reed and Miller, pp. 35-41.

- ↑ Colony of New Jersey Archives, p. 23:328.

- ↑ Colony of New Jersey Archives, p. 21:384.

- ↑ Blackman 1880, pp. 244,245,281.

- ↑ Blackman 1880, p. 178.

- ↑ Heston 1924, p. 1:206.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Blackman 1880, p. 249.

- ↑ Blackman 1880, pp. 178,244-245.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Society of Friends, p. 4.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Blackman 1880, p. 196.

- ↑ Blackman, p. 198.

- ↑ Society of Friends undated, p. 24.

- ↑ Blackman 1880, pp. 227-228.

- ↑ Blackman 1880, p. 228.

- ↑ Colony of New Jersey West Jersey Deeds, p. 66.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 Colony of New Jersey Record of Wills, 1734-1743, p. 362.

- ↑ Criminger 1984, pp. 6-7,16-17.

- ↑ Criminger 1984, pp. 18-19.

- ↑ Blackman 1880, pp. 202,246.

- ↑ Criminger, pp. 24-26.

- ↑ Criminiger, p. 26-27.

- ↑ Arnold, pp. 4-5.

- ↑ Fortenberry Family Association.

- ↑ Criminger, pp. 325-326.

- ↑ Criminger, pp. 41-44.

- ↑ Criminger, pp. 249-250.

- ↑ Criminger, pp. 280-281.

- ↑ Arnold, pp. 22-23.

- ↑ Arnold, pp. 24-27.

- ↑ Jackson and Poulson, p. 156.

- ↑ Roberts 2009, pp. 169-172.

- ↑ Blackman 1880, pp. 242-248.

- ↑ Criminger 1984.

- ↑ Arnold 1989.

- ↑ Fortenberry 1997.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

- Armstrong, Edward, ed. Record of Upland Court, 1676-1681, Historical Society of Pennsylvania Memoirs. vol. 7.

- Colonial Society of Pennsylvania (1904). Records of the Court of New Castle on Delaware. Lancaster, Pennsylvania: The Colonial Society of Pennsylvania.

- Colony of New Jersey. New Jersey Archives, first series.

- Colony of New Jersey. Record of Wills, 1734-1743. vol.4. LDS Microfilm 0522715.

- Colony of New Jersey. West Jersey Deeds. vol.BBB.

- Cook, Lewis D. "Two Assessment Lists of Settlers on the Delaware River Shores, 1677". The Genealogical Magazine of New Jersey 13 (1 (Jan 1938)).

- Cripps, John (1682). "A True Account of the Dying Words of Ockanickon, an Indian King, Spoken to Jahkursoe, His Brother's Son, Whom He Appointed King After Him". In Norman Penney. The Journal of the Friends Historical Society. IX (1912): 164. Retrieved 2011-01-08.

- Danckaerts, Jasper (1913). Bartlett James and J. Franklin Jameson, ed. Journal of Jasper Danckaerts, 1679-1680. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Gehring, Charles T. New York Historical Manuscripts: Delaware Papers (Dutch Period) 1648-1664, vols. 18-19; Delaware Papers (English Period), 1664-1682, vols. 20-21.

- Nelson, William (1901). Documents Relating to the Colonial History of the State of New Jersey. XXIII (Calendar of New Jersey Wills).

- Reed, H. Clay; Miller, George J. (1944). The Burlington Court Book, A Record of Quaker Jurisprudence in West New Jersey, 1680-1709. Washington D.C.: The American Historical Association.

- Ricord, Frederick W.; Nelson, Wm. (1886). Documents Relating to the Colonial History of the State of New Jersey. vol.X (Administration of Governor William Franklin, 1767-1776). Newark: Daily Advertiser Publishing House.

- Society of Friends (undated [covers years 1779-1886]). Friends' Meeting Minutes, Little Egg Harbor, New Jersey, Births and Burials, 1779-1886. LDS Microfilm 0020464. Records from as early as 1698 are also included.

- Society of Friends (undated [covers years 1698-1769]). Friends Society of Little Egg Harbor Monthly Meeting, N.J. Swarthmore College, Pennsylvania. This is a folder of typescript pages apparently containing information pulled from original records.

- Whitehead, William A. (1880). Documents Relating to the Colonial History of the State of New Jersey. vol.I. Newark, New Jersey: The Daily Journal Establishment.

Secondary Sources

- Arnold, Stanley W. (1989). The Fortenberry Family of Northeastern Arkansas. Little Rock, Arkansas: privately published.

- Barber, John W.; Howe, Henry (1846). Historical Collections of the State of New Jersey. New York: S. Tuttle.

- Blackman, Leah (1880). History of Little Egg Harbor Township, Burlington County, New Jersey. Retrieved 2010-10-21.

- Craig, Dr. Peter Stebbins (1999). 1671 Census of the Delaware. published by the author. ISBN 1-887099-10-7.

- Craig, Dr. Peter Stebbins (2002). "Sinnick Broer the Finn and his Sinex, Sinnickson, & Falkenberg Descendants". Swedish Colonial News 2 (7 (Fall 2002)).

- Criminger, Adrianne Fortenberry (1984). The Fortenberry Families of Southern Mississippi. Easley, South Carolina: Southern Historical Press. ISBN 0-89308-529-4.

- Fortenberry Family Association (1992). The J. C. Fortenberry I Family Record. privately published.

- Fortenberry, John and Maxine (1997). The Fortenberry Family in Arkansas. Little Rock, Arkansas: privately published.

- Heston, Alfred M., editor (1924). South Jersey, A History, 1664-1924. New York and Chicago: Lewis Historical Publishing Company.

- Jackson, Ronald Vern; Poulson, Altha (1981). American Patriots. privately published.

- Roberts, Gary Boyd (2009). Ancestors of American Presidents, 2009 edition. Boston, Massachusetts: New England Historic Genealogical Society. ISBN 978-0-88082-220-6.

- Stewart, Frank H. (1932). Indians of Southern New Jersey. Woodbury, New Jersey: Gloucester County Historical Society.

- Woodward, Major E. M. (1883). History of Burlington County New Jersey.

Further reading

- Honeyman, A. Van Doren (1918). Documents Relating to the Colonial History of the State of New Jersey. XXX (Calendar of New Jersey Wills, Administrations, etc.).

External links

- Burlington Island Retrieved 2011-01-16

- A line of descent from Hendrick Jacobs Falkenberg by Don Falkenburg Personal website detailing a line of descent for nine generations, retrieved 2010-10-27

- A line of descent from Hendrick Jacobs Falkenberg by Marie E. Velardi Personal website showing six generations of Falkenbergs, retrieved 2010-10-27

- Marker in honor of the Lenape Indian King Ockanickon Ockanickon's dying words were interpreted by Falkenberg in 1681. Retrieved 2011-01-16