Heaviside cover-up method

The Heaviside cover-up method, named after Oliver Heaviside, is one possible approach in determining the coefficients when performing the partial-fraction expansion of a rational function.[1]

Method

Separation of a fractional algebraic expression into partial fractions is the reverse of the process of combining fractions by converting each fraction to the lowest common denominator (LCM) and adding the numerators. This separation can be accomplished by the Heaviside cover-up method, another method for determining the coefficients of a partial fraction. Case one has fractional expressions where factors in the denominator are unique. Case two has fractional expressions where some factors may repeat as powers of a binomial.

In integral calculus we would want to write a fractional algebraic expression as the sum of its partial fractions in order to take the integral of each simple fraction separately. Once the original denominator, D0, has been factored we set up a fraction for each factor in the denominator. We may use a subscripted D to represent the denominator of the respective partial fractions which are the factors in D0. Letters A, B, C, D, E, and so on will represent the numerators of the respective partial fractions. When a partial fraction term has a single (i.e. unrepeated) binomial in the denominator, the numerator is called a residue.

We calculate each respective numerator by (1) taking the root of the denominator (i.e. the value of x that makes the denominator zero) and (2) then substituting this root into the original expression but ignoring the corresponding factor in the denominator. Each root for the variable is the value which would give an undefined value to the expression since we do not divide by zero.

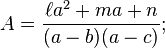

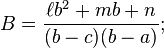

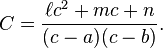

General formula for a cubic denominator with three distinct roots:

Where x = a and

and where x = b and

and where x = c and

Case one

Factorize the expression in the denominator. Set up a partial fraction for each factor in the denominator. Apply the cover-up rule to solve for the new numerator of each partial fraction.

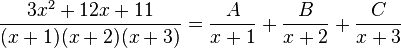

Example

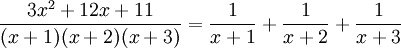

Set up a partial fraction for each factor in the denominator. With this framework we apply the cover-up rule to solve for A, B, and C.

1. D1 is x + 1; set it equal to zero. This gives the residue for A when x = −1.

2. Next, substitute this value of x into the fractional expression, but without D1.

3. Put this value down as the value of A.

Proceed similarly for B and C.

D2 is x + 2; For the residue B use x = −2.

D3 is x + 3; For residue C use x = −3.

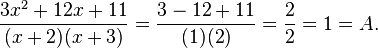

Thus, to solve for A, use x = −1 in the expression but without D1:

Thus, to solve for B, use x = −2 in the expression but without D2:

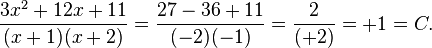

Thus, to solve for C, use x = −3 in the expression but without D3:

Thus,

Case two

When factors of the denominator include powers of one expression we

- Set up a partial fraction for each unique factor and each lower power of D;

- Set up an equation showing the relation of the numerators if all were converted to the LCD.

From the equation of numerators we solve for each numerator, A, B, C, D, and so on. This equation of the numerators is an absolute identity, true for all values of x. So, we may select any value of x and solve for the numerator.

Example

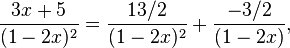

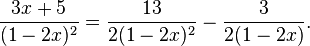

Here, we set up a partial fraction for each descending power of the denominator. Then we solve for the numerators, A and B. As (1-2x) is a repeated factor, we now need to find two numbers, as so we need an additional relation in order to solve for both.

To write the relation of numerators the second fraction needs another factor of (1-2x) to convert it to the LCD, giving us 3x + 5 = A + B(1 − 2x). In general, if a binomial factor is raised to the power of n, then n constants A_k will be needed, each appearing divided by successive powers,  , where k runs from 1 to n. The cover-up rule can be used to find A_n, but is still A_1 that is called the residue. Here, n = 2, A = A_2, and B = A_1

, where k runs from 1 to n. The cover-up rule can be used to find A_n, but is still A_1 that is called the residue. Here, n = 2, A = A_2, and B = A_1

To solve for A: A can be solved by setting the denominator of the first fraction to zero, 1 − 2x = 0. Solving for x gives the cover-up value for A, when x = ½. When we substitute this value, x = ½, into the relation of numerators we have 3(1/2) + 5 = A + B(0). Solving for A gives us A = 3/2 + 5 = 13/2. Hence, numerator A equals six and one-half.

To solve for B: Since the equation of the numerators, here, 3x + 5 = A + B(1 − 2x), is true for all values of x, pick a value for x and use it to solve for B. As we have solved for the value of A above, A = 13/2, we may use that value to solve for B.

We may pick x = 0, use A = 13/2, and then solve for B.

- 3x + 5 = A + B(1 − 2x)

- 0 + 5 = 13/2 + B(1 + 0)

- 10/2 = 13/2 + B

- −3/2 = B

We may pick x = 1. Then solve for B:

- 3x + 5 = A + B(1 − 2x)

- 3 + 5 = 13/2 + B(1 − 2)

- 8 = 13/2 + B(−1)

- 16/2 = 13/2 − B

- B = −3/2

We may pick x = −1. Solve for B:

- 3x + 5 = A + B(1 − 2x)

- −3 + 5 = 13/2 + B(1 + 2)

- 4/2 = 13/2 + 3B

- −9/2 = 3B

- −3/2 = B

Hence,

or

References

- ↑ Calculus and Analytic Geometry 7th Edition, Thomas/Finney, 1988, pp. 482-489