Haptotaxis

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

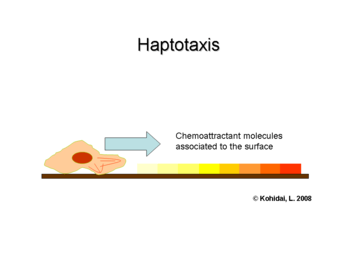

Haptotaxis (from Greek ἅπτω (hapto, "touch, fasten") and τάξις (taxis, "arrangement, order")) is the directional motility or outgrowth of cells, e.g. in the case of axonal outgrowth, usually up a gradient of cellular adhesion sites or substrate-bound chemoattractants (the gradient of the chemoattractant being expressed or bound on a surface, in contrast to the classical model of chemotaxis, in which the gradient develops in a soluble fluid.). These gradients are naturally present in the extracellular matrix (ECM) of the body during processes such as angiogenesis or artificially present in biomaterials where gradients are established by altering the concentration of adhesion sites on a polymer substrate.[1][2]

References

- ↑ McCarthy JB, Palm SL, Furcht LT. (1983). "Migration by haptotaxis of a Schwann cell tumor line to the basement membrane glycoprotein laminin". J Cell Biol 97 (3): 772–7. doi:10.1083/jcb.97.3.772. PMC 2112555. PMID 6885918.

- ↑ Cattaruzza S, Perris R. (2005). "Proteoglycan control of cell movement during wound healing and cancer spreading". Matrix Biol 24 (6): 400–17. doi:10.1016/j.matbio.2005.06.005. PMID 16055321.

External links

- "Cellular Migration" - University of California, Berkeley, 2003. Cell and Tissue Engineering website.

This article is issued from Wikipedia. The text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share Alike; additional terms may apply for the media files.