Hanseatic League

Hanse Hansa Hanseatic League |

||

|---|---|---|

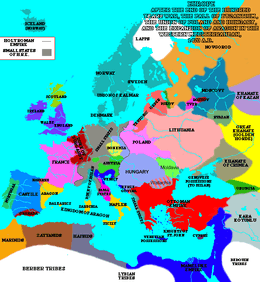

Northern Europe in 1400, showing the extent of the Hansa.

|

||

| Capital | Lübeck | |

| Lingua franca | Middle Low German | |

| Membership | see list below | |

| Establishment | 1358 | |

The Hanseatic League (also known as the Hanse or Hansa; Low German: Hanse, Dudesche Hanse, Latin: Hansa, Hansa Teutonica or Liga Hanseatica) was a commercial and defensive confederation of merchant guilds and their market towns that dominated trade along the coast of Northern Europe. It stretched from the Baltic to the North Sea and inland during the Late Middle Ages and early modern period (c. 13th to 17th centuries).

The League was created to protect economic interests and diplomatic privileges in the cities and countries and along the trade routes the merchants visited. The Hanseatic cities had their own legal system and furnished their own armies for mutual protection and aid. Despite this, the organization was not a city-state, nor can it be called a confederation of city-states; only a very small number of the cities within the league enjoyed autonomy and liberties comparable to those of a free imperial city.[1]

The legacy of the Hansa is remembered today in several names, for example the German airline Lufthansa (i.e., "Air Hansa"), F.C. Hansa Rostock, the Hanze University of Applied Sciences, Groningen, in the Netherlands, the Hansa Brewery in Bergen, the Hansabank in Baltic states (now known as Swedbank) and the Hanse Sail in Rostock. DDG Hansa was a major German shipping company from 1881 until its bankruptcy in 1980.

History

Historians generally trace the origins of the League to the rebuilding of the North German town of Lübeck in 1159 by the powerful Henry the Lion, Duke of Saxony and Bavaria, after Henry had captured the area from Adolf II, Count of Schauenburg and Holstein.

Exploratory trading adventures, raids and piracy had happened earlier throughout the Baltic (see Vikings) – the sailors of Gotland sailed up rivers as far away as Novgorod, for example – but the scale of international trade economy in the Baltic area remained insignificant before the growth of the Hanseatic League.[citation needed]

German cities achieved domination of trade in the Baltic with striking speed over the 13th century, and Lübeck became a central node in the seaborne trade that linked the areas around the North and Baltic Seas. The 15th century saw the peak of Lübeck's hegemony.

Foundation and formation

Lübeck became a base for merchants from Saxony and Westphalia trading eastward and northward. Well before the term Hanse appeared in a document (1267)[2], merchants in different cities began to form guilds or Hansa with the intention of trading with towns overseas, especially in the economically less-developed eastern Baltic. This area was a source of timber, wax, amber, resins, furs, along with rye and wheat brought down on barges from the hinterland to port markets. The towns raised their own armies, with each guild being required to provide levies when needed. The Hanseatic cities came to each other's aid, and commercial ships often had to be used to carry soldiers and their arms.

Visby functioned as the leading centre in the Baltic before the Hansa. Sailing east, Visby merchants established a trading post at Novgorod, and they called it Gutagard (it was also known as Gotenhof). This was established in 1080.[3] Merchants from northern Germany at first also stayed in this Gotlander settlement. Yet later, they established their own trading station in Novgorod, known as Peterhof, which was further up from the river. This took place in the first half of the 13th century.[4] In 1229, German merchants at Novgorod were granted certain privileges, which made their position more secure.[5]

Before the foundation of the League in 1356 the word Hanse did not occur in the Baltic language. The Gotlanders used the word varjag.

Hansa societies worked to remove restrictions to trade for their members. For example, the merchants of the Cologne Hansa convinced Henry II, King of England to free them (1157) from all tolls in London and allow them to trade at fairs throughout England. The "Queen of the Hansa", Lübeck, where traders were required to trans-ship goods between the North Sea and the Baltic, gained the Imperial privilege of becoming a free imperial city in 1227, as previously its later partner Hamburg in 1189.

In 1241, Lübeck, which had access to the Baltic and North Sea fishing grounds, formed an alliance—a precursor of the League—with Hamburg, another trading city, which controlled access to salt-trade routes from Lüneburg. The allied cities gained control over most of the salt-fish trade, especially the Scania Market; and Cologne joined them in the Diet of 1260. In 1266, Henry III granted the Lübeck and Hamburg Hansa a charter for operations in England, and the Cologne Hansa joined them in 1282 to form the most powerful Hanseatic colony in London. Much of the drive for this co-operation came from the fragmented nature of existing territorial government, which failed to provide security for trade. Over the next 50 years the Hansa itself emerged with formal agreements for confederation and co-operation covering the west and east trade routes. The principal city and linchpin remained Lübeck; with the first general Diet of the Hansa held there in 1356, the Hanseatic League acquired an official structure.[6]

According to Dutch Historical Records from A Brief History of Groningen - Compiled and translated by Erik Springelkamp:[7] In 1258 traders from Groningen acquired the right to trade in England, and got privileges for the trade in Holland. Groningen was a member of the then informally-organized Hanseatic League. In 1227 two Groningers were witness in Gotland, Sweden at a treaty between the Hansa and the prince of Smolensk. There were regular relations with both Hamburg and Bremen. In 1273 the abbot of Aduard got the right from the Archbishop of Hamburg to trade in Stade on the Elbe.

During the period from 1300 to 1500 the active (long-range) trade of Groningen diminished, as did the position of the city in the Hanseatic League. In 1358 the city of Lübeck sent letters to all Hansa members about a trade-boycott of Flanders but Groningen didn't receive this letter. The Mayor and City Council complained, but said they would comply with the boycott of their southern neighbours. Ten years later Groningen wasn't part of a Hansa fleet against King Waldemar of Denmark to protect the free navigation through the Sont. Still, the city was a member, and in the early 15th century there was an Hansa assembly in Groningen.

Expansion

Lübeck's location on the Baltic provided access for trade with Scandinavia and Kiev Rus, putting it in direct competition with the Scandinavians who had previously controlled most of the Baltic trade routes. A treaty with the Visby Hansa put an end to competition: through this treaty the Lübeck merchants also gained access to the inland Russian port of Novgorod, where they built a trading post or Kontor (literally: office). Other such alliances formed throughout the Holy Roman Empire. Yet the League never became a closely managed formal organisation. Assemblies of the Hanseatic towns met irregularly in Lübeck for a Hansetag (Hanseatic Diet), from 1356 onwards, but many towns chose not to send representatives and decisions were not binding on individual cities.[citation needed] Over time, the network of alliances grew to include a flexible roster of 70 to 170 cities.[8]

The league succeeded in establishing additional Kontors in Bruges (Flanders), Bergen (Norway), and London (England). These trading posts became significant enclaves. The London Kontor, established in 1320, stood west of London Bridge near Upper Thames Street, the site now occupied by Cannon Street station. It grew significantly over time into a walled community with its own warehouses, weighhouse, church, offices and houses, reflecting the importance and scale of the activity carried on. The first reference to it as the Steelyard (der Stahlhof) occurs in 1422.

Starting with trade in coarse woolen fabrics, the Hanseatic League had the effect of bringing both commerce and industry to northern Germany.[9] As trade increased newer and finer woolen and linen fabrics, and even silks, were manufactured in Northern Germany.[9] The same refinement of the products of industry occurred in other fields, e.g. etching, wood carving, armor production, engraving of metals, and wood-turning. In short, the century-long monopolization of sea navigation and trade by the Hanseatic League ensured that the Renaissance would arrive in Northern Germany long before the rest of Europe.[9]

In addition to the major Kontors, individual Hanseatic ports had a representative merchant and warehouse. In England this happened in Boston, Bristol, Bishop's Lynn (now King's Lynn, which features the sole remaining Hanseatic warehouse in England), Hull, Ipswich, Norwich, Yarmouth (now Great Yarmouth), and York.

The League primarily traded timber, furs, resin (or tar), flax, honey, wheat, and rye from the east to Flanders and England with cloth (and, increasingly, manufactured goods) going in the other direction. Metal ore (principally copper and iron) and herring came southwards from Sweden.

German colonists in the 12th and 13th centuries settled in numerous cities on and near the east Baltic coast, such as Elbing (Elbląg), Thorn (Toruń), Reval (Tallinn), Riga, and Dorpat (Tartu), which became members of the Hanseatic League, and some of which still retain many Hansa buildings and bear the style of their Hanseatic days. Most were granted Lübeck law (Lübisches Recht), which provided that they had to appeal in all legal matters to Lübeck's city council. The Livonian Confederation incorporated modern-day Estonia and parts of Latvia and had its own Hanseatic parliament (diet); all of its major towns became members of the Hanseatic League. The dominant language of trade was Middle Low German, a dialect with significant impact for countries involved in the trade, particularly the larger Scandinavian languages, Estonian, and Latvian.

Zenith

The League had a fluid structure, but its members shared some characteristics. First, most of the Hansa cities either started as independent cities or gained independence through the collective bargaining power of the League, though such independence remained limited. The Hanseatic free cities owed allegiance directly to the Holy Roman Emperor, without any intermediate tie to the local nobility.

Another similarity involved the cities' strategic locations along trade routes. At the height of its power in the late 14th century, the merchants of the Hanseatic League succeeded in using their economic clout and sometimes their military might—trade routes required protection and the League's ships sailed well-armed—to influence imperial policy.

The League also wielded power abroad. Between 1361 and 1370, the League waged war against Denmark. Initially unsuccessful, Hanseatic towns in 1368 allied in the Confederation of Cologne, sacked Copenhagen and Helsingborg, and forced Valdemar IV, King of Denmark, and his son-in-law Haakon VI, King of Norway, to grant the League 15% of the profits from Danish trade in the subsequent peace treaty of Stralsund in 1370, thus gaining an effective trade and political monopoly in Scandinavia. This favourable treaty was the high-water mark of Hanseatic power. The commercial privileges were renewed in the Treaty of Vordingborg, 1435.[10][11][12]

The Hansa also waged a vigorous campaign against pirates. Between 1392 and 1440, maritime trade of the League faced danger from raids of the Victual Brothers and their descendants, privateers hired in 1392 by Albert of Mecklenburg, King of Sweden against Margaret I, Queen of Denmark. In the Dutch–Hanseatic War (1438–41), the merchants of Amsterdam sought and eventually won free access to the Baltic and broke the Hansa monopoly. As an essential part of protecting their investment in trade and ships, the League trained pilots and erected lighthouses.

Most foreign cities confined the Hansa traders to certain trading areas and to their own trading posts. They seldom interacted with the local inhabitants, except when doing business. Many locals, merchant and noble alike, envied the power of the League and tried to diminish it. For example, in London the local merchants exerted continuing pressure for the revocation of the privileges of the League. The refusal of the Hansa to offer reciprocal arrangements to their English counterparts exacerbated the tension. King Edward IV of England reconfirmed the league's privileges in the Treaty of Utrecht (1474) despite this hostility, in part thanks to the significant financial contribution the League made to the Yorkist side during The Wars of the Roses. In 1597, Queen Elizabeth I of England expelled the League from London and the Steelyard closed the following year. Ivan III of Russia closed the Hanseatic Kontor at Novgorod in 1494. The very existence of the League and its privileges and monopolies created economic and social tensions that often crept over into rivalry between League members.[13]

Rise of rival powers

The economic crises of the late 15th century did not spare the Hansa. Nevertheless, its eventual rivals emerged in the form of the territorial states, whether new or revived, and not just in the west: Poland triumphed over the Teutonic Knights in 1466; Ivan III, Grand Prince of Moscow, ended the entrepreneurial independence of Hansa's Novgorod Kontor in 1478. New vehicles of credit imported from Italy outpaced the Hansa economy, in which silver coin changed hands rather than bills of exchange.

In the 15th century, tensions between the Prussian region and the "Wendish" cities (Lübeck and its eastern neighbours) increased. Lübeck was dependent on its role as centre of the Hansa, being on the shore of the sea without a major river. It was on the entrance of the land route to Hamburg, but this land route could be bypassed by sea travel around Denmark and through the Sound. Prussia's main interest, on the other hand, was primarily the export of bulk products like grain and timber, which were very important for England, the Low Countries, and later on also for Spain and Italy.

In 1454, the year of the marriage of Elisabeth of Austria to the Jagiellonian king, the towns of the Prussian Confederation rose against the dominance of the Teutonic Order and asked Casimir IV, King of Poland for help. Danzig, Thorn, and Elbing became part of the Kingdom of Poland, (1466–1569 referred to as Royal Prussia) by the Second Peace of Thorn (1466). Poland in turn was heavily supported by the Holy Roman Empire through family connections and by military assistance under the Habsburgs. Kraków, then the capital of Poland, had a loose association with Hansa.[14] The lack of customs borders on the River Vistula after 1466 helped to gradually increase Polish grain export, transported to the sea down the Vistula, from 10,000 tonnes per year in the late 15th century to over 200,000 tonnes in the 17th century.[15] The Hansa-dominated maritime grain trade made Poland one of the main areas of its activity, helping Danzig to become the Hansa's largest city.

The member cities took responsibility for their own protection. In 1567, a Hanseatic League Agreement reconfirmed previous obligations and rights of League members, such as common protection and defense against enemies.[16] The Prussian Quartier cities of Thorn, Elbing, Königsberg and Riga and Dorpat also signed. When pressed by the king of Poland–Lithuania, Danzig remained neutral and would not allow ships running for Poland into its territory. They had to anchor somewhere else, such as at Pautzke (now Puck, Poland).

A major benefit for the Hansa was its control of the shipbuilding market, mainly in Lübeck and in Danzig. The Hansa sold ships everywhere in Europe, including Italy. They drove out the Dutch, because Holland wanted to favour Bruges as a huge staple market at the end of a trade route. When the Dutch started to become competitors of the Hansa in shipbuilding, the Hansa tried to stop the flow of shipbuilding technology from Hansa towns to Holland. Danzig, a trading partner of Amsterdam, tried to stall the decision. Dutch ships sailed to Danzig to take grain from the city directly, to the dismay of Lübeck. Hollanders also circumvented the Hansa towns by trading directly with North German princes in non-Hansa towns. Dutch freight costs were much lower than those of the Hansa, and the Hansa were excluded as middlemen.

When Bruges, Antwerp and Holland all became part of the Duchy of Burgundy they actively tried to take over the monopoly of trade from the Hansa, and the staples market from Bruges was transferred to Amsterdam. The Dutch merchants aggressively challenged the Hansa and met with much success. Hanseatic cities in Prussia, Livonia supported the Dutch against the core cities of the Hansa in northern Germany. After several naval wars between Burgundy and the Hanseatic fleets, Amsterdam gained the position of leading port for Polish and Baltic grain from the late 15th century onwards. The Dutch regarded Amsterdam's grain trade as the mother of all trades (Moedernegotie). Denmark and England tried to destroy the Netherlands in the First Navigation War (1652–54).[17] The war ended in a truce, but the Anglo-Dutch rivalry continued.[17]:401 A Second Dutch Navigation War (1665–67) broke out which also ended inconclusively.[17]:411 Later, there was a Third Navigation War (1672–74), which also resulted in another failed attempt to destroy Holland.[17]:414

Nuremberg in Franconia developed an overland route to sell formerly Hansa-monopolised products from Frankfurt via Nuremberg and Leipzig to Poland and Russia, trading Flemish cloth and French wine in exchange for grain and furs from the east. The Hansa profited from the Nuremberg trade by allowing Nurembergers to settle in Hansa towns, which the Franconians exploited by taking over trade with Sweden as well. The Nuremberger merchant Albrecht Moldenhauer was influential in developing the trade with Sweden and Norway, and his sons Wolf and Burghard established themselves in Bergen and Stockholm, becoming leaders of the Hanseatic activities locally.

End of the Hansa

At the start of the 16th century, the League found itself in a weaker position than it had known for many years. The rising Swedish Empire had taken control of much of the Baltic. Denmark had regained control over its own trade, the Kontor in Novgorod had closed, and the Kontor in Bruges had become effectively moribund. The individual cities which made up the League had also started to put self-interest before their common Hanseatic interests. Finally, the political authority of the German princes had started to grow—and so to constrain the independence of action which the merchants and Hanseatic towns had enjoyed.

The League attempted to deal with some of these issues. It created the post of Syndic in 1556 and elected Heinrich Sudermann as a permanent official with legal training, who worked to protect and extend the diplomatic agreements of the member towns. In 1557 and 1579 revised agreements spelled out the duties of towns and some progress was made. The Bruges Kontor moved to Antwerp and the Hansa attempted to pioneer new routes. However, the League proved unable to halt the progress around it and so a long decline commenced. The Antwerp Kontor closed in 1593, followed by the London Kontor in 1598. The Bergen Kontor continued until 1754; its buildings alone of all the Kontore survive (see Bryggen).

The gigantic Adler von Lübeck warship, which was constructed for military use against Sweden during the Northern Seven Years' War (1563–70), but never put to military use, epitomized the vain attempts of Lübeck to uphold its long-privileged commercial position in a changed economic and political climate.

By the late 16th century, the League had imploded and could no longer deal with its own internal struggles, the social and political changes that accompanied the Protestant Reformation, the rise of Dutch and English merchants, and the incursion of the Ottoman Empire upon its trade routes and upon the Holy Roman Empire itself. Only nine members attended the last formal meeting in 1669 and only three (Lübeck, Hamburg and Bremen) remained as members until its final demise in 1862.[18][19]

Despite its collapse, several cities still maintain the link to the Hanseatic League today. The Dutch cities of Groningen, Deventer, Kampen, Zutphen, and the ten German cities Bremen, Demmin, Greifswald, Hamburg, Lübeck, Lüneburg, Rostock, Stade, Stralsund and Wismar still call themselves Hanse cities. Lübeck, Hamburg, and Bremen continue to style themselves officially as "Free (and) Hanseatic Cities." (Rostock's football team is named F.C. Hansa Rostock in memory of the city's trading past.) For Lübeck in particular, this anachronistic tie to a glorious past remained especially important in the 20th century. In 1937 the Nazi Party removed this privilege through the Greater Hamburg Act after the Senat of Lübeck did not permit Adolf Hitler to speak in Lübeck during his election campaign.[20] He held the speech in Bad Schwartau, a small village on the outskirts of Lübeck. Subsequently, he referred to Lübeck as "the small city close to Bad Schwartau." After the EU enlargement to the East in May 2004 there are some experts who wrote about the resurrection of the Baltic Hansa.[21]

Organization

The members of the Hanseatic League were Low German merchants as well as the towns where, with the exception of Dinant, these merchants held citizenship. Not all towns with Low German merchant communities were members of the league (e.g., Emden, Memel (Klaipėda), Vyborg and Narva never joined). On the other hand, Hanseatic merchants could also come from settlements without German town law—the premise for league membership was birth to German parents, subjection to German law, and a commercial education. The league served to further and defend the common interests of its heterogeneous members: commercial ambitions such as enhancement of trade, and political ambitions such as ensuring maximum independence from the noble territorial rulers.[22]:10–11

Decisions and actions of the Hanseatic League were the consequence of a consensus-based procedure. If an issue arose, the league's members were invited to participate in a central meeting, the Tagfahrt (lit. "meeting ride," sometimes also referred to as Hansetag, since 1358). The member communities then chose envoys (Ratssendeboten) to represent their local consensus on the issue at the Tagfahrt. Not every community sent an own envoy, delegates were often entitled to represent a set of communities. Consensus-building on local and Tagfahrt levels followed the Low Saxon tradition of Einung, where consensus was defined as absence of protest: after a discussion, the proposals which gained sufficient support were dictated aloud to the scribe and passed as binding Rezess if the attendees did not object; those favouring alternative proposals unlikely to get sufficient support were obliged to remain silent during this procedure. If consensus could not be established on a certain issue, consensus was established instead on the appointment of a number of league members who were then empowered to work out a solution.[22]:70–72

The Hanseatic kontors each had an own treasury, court and seal. Like the guilds, the kontors were led by Ältermänner (sing. Ältermann, lit. "elderman," cf. English aldermen). The Stalhof kontor, as a special case, had a Hanseatic and an English Ältermann. In 1347, the kontor of Brussels modified its statute to ensure an equal representation of the league's members. To that end, member communities from different regions were pooled into three circles (Drittel, lit. "third [part]"): the Wendish and Saxon Drittel, the Westphalian and Prussian Drittel as well as the Gothlandian, Livonian and Swedish Drittel. The merchants from the respective Drittel would then each choose two Ältermänner and six members of the Eighteen Men's Council (Achtzehnmännerrat) to administer the kontor for a set period of time. In 1356, during a Hanseatic meeting in preparation of the first Tagfahrt, the league confirmed this statute. The division into Drittel was gradually adopted and institutionalized by the league in general (see table).[22]:62–63;[23][24][25]

| Drittel (1356–1554) | Regions | Chief city (Vorort) |

|---|---|---|

| Wendish-Saxon | Holstein, Saxony, Mecklenburg, Pomerania, Brandenburg | Lübeck |

| Westphalian-Prussian | Westphalia, Rhineland, Prussia | Dortmund, later Cologne |

| Gothlandian-Livonian-Swedish | Gothland, Livonia, Sweden | Visby, later Rīga |

The Tagfahrt or Hansetag was the only central institution of the Hanseatic league. However, with the division in Drittel, the members of the respective subdivisions frequently held Dritteltage (lit. "Drittel meeting") to work out common positions which could then be presented at a Tagfahrt. On a more local level, league members also met, and while such regional meetings were never formalized into a Hanseatic institution, they gradually gained importance in the process of preparing and implementing Tagfahrt decisions.[26]

Quarters

From 1554, the division into Drittel was modified to reduce the circles' heterogeneity, enhance the collaboration of the members on a local level and thus make the league's decision-making process more efficient.[27] The number of circles rose to four, so they were called Quartiere (quarters):[23]

| Quartier (since 1554) | Chief city (Vorort) |

|---|---|

| Wendish and Pomeranian[28] | Lübeck[28] |

| Saxon, Thuringian and Brandenburg[28] | Brunswick,[28] Magdeburg[citation needed] |

| Prussia, Livonia and Sweden[28]—or East Baltic[29]:120 | Danzig (now Gdańsk)[28] |

| Rhine, Westphalia and The Netherlands[28] | Cologne[28] |

This division was however not adopted by the depots (Kontore), who for their purposes (like Ältermänner elections) grouped the league members in different ways (e.g., the division adopted by the Stahlhof in London in 1554 grouped the league members into Dritteln, whereby Lübeck merchants represented the Wendish, Pomeranian Saxon and several Westphalian towns, Cologne merchants represented the Cleves, Mark, Berg and Dutch towns, while Danzig merchants represented the Prussian and Livonian towns).[30]

Lists of former Hansa cities

The names of the Quarters have been abbreviated in the following table:

- Wendish: Wendish and Pomeranian[28] (or just Wendish)[29]:120 Quarter

- Saxon: Saxon, Thuringian and Brandenburg[28] (or just Saxon)[29]:120 Quarter

- Baltic: Prussian, Livonian and Swedish[28] (or East Baltic)[29]:120 Quarter

- Westphalian: Rhine-Westphalian and Netherlands[28] (or Rhineland)[29]:120 Quarter

- Kontor: The Kontore were foreign trading posts of the League, not cities that were Hanseatic members.

The column "Territory" indicates the jurisdiction to which the city was, at the time, subject; the column "Now" indicates the modern nation-state in which the city may be found and the columns "From" and "Until" record the dates at which the city joined and/or left the league.

| Quarter | City | Territory | Now | From | Until | Notes | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wendish | |

|

|

Capital of the Hanseatic League, capital of the Wendish and Pomeranian Circle | [25][28][29]:47, 120;[31][32]:74, 82;[33] | ||

| Wendish | |

|

|

[25][29]:47;[31][32]:82;[34] | |||

| Wendish | |

|

|

[25][31][33][34][35] | |||

| Wendish | |

|

|

Joined the 10-year Rostock Peace Treaty (Rostocker Landfrieden) in 1283, which was the predecessor of the federation of Wendish towns (1293 onwards). | [25][31][32]:82;[33][34][36] | ||

| Wendish | |

|

|

Joined the 10-year Rostock Peace Treaty in 1283, which was the predecessor of the federation of Wendish towns (1293 onwards). | [25][31][32]:82;[33][34][36][37] | ||

| Wendish | |

|

|

1293 | Rügen was a fief of the Danish crown to 1325. Stralsund joined the 10-year Rostock Peace Treaty in 1283, which was the predecessor of the federation of Wendish towns (1293 onwards). From 1339 to the 17th century, Stralsund was a member of the Vierstädtebund with Greifswald, Demmin and Anklam. | [25][31][33][34][36][38] | |

| Wendish | |

|

|

Joined the 10-year Rostock Peace Treaty in 1283, which was the predecessor of the federation of Wendish towns (1293 onwards). From 1339 to the 17th century, Demmin was a member of the Vierstädtebund with Stralsund, Greifswald and Anklam. | [25][33][36][39] | ||

| Wendish | |

|

|

Joined the 10-year Rostock Peace Treaty in 1283, which was the predecessor of the federation of Wendish towns (1293 onwards). From 1339 to the 17th century, Griefswald was a member of the Vierstädtebund with Stralsund, Demmin and Anklam. | [25][33][34][36][39] | ||

| Wendish | |

|

|

Joined the 10-year Rostock Peace Treaty in 1283, which was the predecessor of the federation of Wendish towns (1293 onwards). From 1339 to the 17th century, Anklam was a member of the Vierstädtebund with Stralsund, Greifswald and Demmin. | [25][33][36][39] | ||

| Wendish | |

|

|

1278 | Joined the 10-year Rostock Peace Treaty in 1283, which was the predecessor of the federation of Wendish towns (1293 onwards); since the 14th century gradually adopted the role of a chief city for the Pomeranian Hanseatic towns to its east | [25][29]:120;[31][33][35][36] | |

| Wendish | |

|

|

||||

| Wendish | |

|

|

[25][33][35][39] | |||

| Wendish | |

|

|

[25][33][34][35][39] | |||

| Wendish | |

|

|

[33][35][39] | |||

| Wendish | |

|

|

1470 | In 1285 at Kalmar, the League agreed with Magnus III, King of Sweden, that Gotland be joined with Sweden.[citation needed] In 1470, Visby's status was rescinded by the League, with Lübeck razing the city's churches in May 1525. | [25][31][33][40] | |

| Wendish | |

|

|

[31][33] | |||

| Saxon | |

|

|

13th century | 17th century | Capital of the Saxon, Thuringian and Brandenburg Circle | [25][28][31][33][34][35] |

| Saxon | |

|

|

1260 | [25][31][33][34][37] | ||

| Saxon | |

|

|

13th century | Capital of the Saxon, Thuringian and Brandenburg Circle | [25][31][33][34][35] | |

| Saxon | |

|

|

1267 | 1566 | Goslar was a fief of Saxony until 1280. | [25][31][33][34][35] |

| Saxon | |

|

|

[25][31][33] | |||

| Saxon | |

|

|

[25][34] | |||

| Saxon | |

|

|

1442 | Brandenburg was raised to an Electorate in 1356. Elector Frederick II caused all the Brandenburg cities to leave the League in 1442. | [29]:120;[31][32]:32;[33][35] | |

| Saxon | |

|

|

1430 | 1442 | Elector Frederick II caused all the Brandenburg cities to leave the League in 1442. | [31][32]:32[33][35] |

| Baltic | |

|

|

1358 | Capital of the Prussian, Livonian and Swedish (or East Baltic) Circle. Danzig had been first a part of the Duchy of Pomerelia, a fief of the Polish Crown, with Polish-Kashubian population, then part of the State of the Teutonic Order from 1308 until 1457. After the Second Peace of Thorn (1466), Royal Prussia including Gdańsk was part of the Kingdom of Poland. | [25][28][29]:120;[31][32]:81; [33][34][35][41]:403 | |

| Baltic | |

|

|

1358 | Elbing had originally been part of the territory of the Old Prussians, until 1230s when it became part of the State of the Teutonic Order. After the Second Peace of Thorn (1466), Royal Prussia, including Elbląg was part of the Kingdom of Poland. | [25][31][33][34][35][41]:452 | |

| Baltic | |

|

|

1280 | Toruń was part of the State of the Teutonic Order from 1233 until 1466. After the Second Peace of Thorn (1466), Royal Prussia, including Toruń, was part of the Kingdom of Poland | [25][31][33][35][41]:436 | |

| Baltic | |

|

|

c. 1370 | c. 1500 | Kraków was the capital of the Kingdom of Poland, 1038–1596/1611. It adopted Magdeburg town law and 5000 Poles and 3500 Germans lived within the city proper in the 15th century; Poles steadily rose in the ranks of guild memberships reaching 41% of guild members in 1500. It was very loosely associated with Hansa, and paid no membership fees, nor sent representatives to League meetings. | [14][31][33][35][42][43][44] |

| Baltic | |

|

|

1387 | 1474 | Breslau, a part of the Duchy of Breslau and the Kingdom of Bohemia, was only loosely connected to the League and paid no membership fees nor did its representatives take part in Hansa meetings | [31][33][35][45][46] |

| Baltic | |

|

|

1340 | Königsberg was the capital of the Teutonic Order, becoming the capital of Ducal Prussia on the Order's secularisation in 1466. Ducal Prussia was a German principality that was a fief of the Polish crown until gaining its independence in the 1660 Treaty of Oliva. The city was renamed Kaliningrad in 1946 after East Prussia was divided between the People's Republic of Poland and the Soviet Union at the Potsdam Conference. | [25][31][33][35] | |

| Baltic | |

|

|

1282 | During the Livonian War (1558–83), Riga became a Free imperial city until the 1581 Treaty of Drohiczyn ceded Livonia to the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth until the city was captured by Sweden in the Polish–Swedish War (1621–1625). | [25][31][32]:82;[33][34][35][47]:20 | |

| Baltic | |

|

|

1285 | On joining the Hanseatic League, Reval was a Danish fief, but was sold, with the rest of northern Estonia, to the Teutonic Order in 1346. After the Livonian War (1558–83), northern Estonia became a part of the Swedish Empire. | [24][25][29]:47;[31][32]:81;[33][35] | |

| Baltic | |

|

|

1280s | The Bishopric of Dorpat gained increasing autonomy within the Terra Mariana. During the Livonian War (1558–83), Dorpat fell under the rule of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, with the 1581 Treaty of Drohiczyn definitively ceding Livonia to the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth until the city was captured by Sweden in the Polish–Swedish War (1621–1625). | [24][25][31][33][35] | |

| Westphalian | |

|

|

1475 | Capital of the Rhine-Westphalian and Netherlands Circle until after the Anglo-Hanseatic War (1470–74), when the city was excluded (German: Verhanst) for having supported England, and Dortmund was made capital of the Circle. | [25][28][29]:120;[31][33][34] | |

| Westphalian | |

|

|

After Cologne was excluded after the Anglo-Hanseatic War (1470–74), Dortmund was made capital of the Rhine-Westphalian and Netherlands Circle. | [25][31][32]:82;[33][34][35] | ||

| Westphalian | |

|

|

1000 | 1500 | [25][31][33][34][37][48][49][50]:438 | |

| Westphalian | |

|

|

1441 | [25][31][33][34][49][50]:433 | ||

| Westphalian | |

|

|

Friesland was de facto independent through much of the Middle Ages. | [25][31][33][37] | ||

| Westphalian | |

|

|

[25][32]:82;[33][34][35] | |||

| Westphalian | |

|

|

12th century | [25][31][33][34][35] | ||

| Westphalian | |

|

|

1609 | The city was a part of the Electorate of Cologne until acquiring its freedom in 1444–49, after which it aligned with the Duchy of Cleves. | [25][31][32]:82;[33][34][35] | |

| Kontor | |

|

|

1500s | Novgorod was one of the principal Kontore of the League and the easternmost. In 1499, Ivan III, Grand Prince of Moscow, closed the Peterhof; it was reopened a few years later, but the League's Russian trade never recovered. | [28][29]:47;[31][32]:26, 82;[37][48] | |

| Kontor | |

|

|

1360 | 1775 | Bryggen was one of the principal Kontore of the League. It was razed by accidental fire in 1476. In 1560, administration of Bryggen was placed under Norwegian administration. | [28][31][32]:82;[37][48][51][52] |

| Kontor | |

|

|

Bruges was one of the principal Kontore of the League until the 15th century, when the seaway to the city silted up; trade from Antwerp benefiting from Bruges's loss. | [29]:47;[31][32]:80;[37][48][50]:134, 176 | ||

| Kontor | |

|

|

1303 | 1853 | The Steelyard was one of the principal Kontore of the League. King Edward I granted a Carta Mercatoria in 1303. The Steelyard was destroyed in 1469 and Edward IV exempted Cologne merchants, leading to the Anglo-Hanseatic War (1470–74). The Treaty of Utrecht, sealing the peace, led to the League purchasing the Steelyard outright in 1475, with Edward having renewed the League's privileges without insisting on reciprocal rights for English merchants in the Baltic. London merchants persuaded Elizabeth I to rescind the League's privileges on 13 January 1598; while the Steelyard was re-established by James I, the advantage never returned. Consulates continued however, providing communication during the Napoleonic Wars, and the Hanseatic interest was only sold in 1853. | [13][29]:47;[31][32]:26, 80–82; [37][48][51][53]:95 |

| Kontor | |

|

|

Antwerp became a major Kontor of the League, particularly after the seaway to Bruges silted up in the 15th century, leading to its fortunes waning in Antwerp's favour, despite Antwerp's refusal to grant special privileges to the League's merchants. Between 1312 and 1406, Antwerp was a margraviate, independent of Brabant. | [31][32]:80;[48] | ||

| Kontor | |

|

|

1751 | The [[List of buildings in King's Lynn#Hanseatic Warehouse|Hanseatic Warehouse]] was constructed in 1475 as part of the Treaty of Utrecht, allowing the League to establish a trading depot in Lynn for the first time. It is the only surviving League building in England. | [31][48][53]:95 | |

| Kontor | |

|

|

[31][48] | |||

| Kontor | |

|

|

15th century | Skåne (Scania) was Danish until ceded to Sweden by the 1658 Treaty of Roskilde, during the Second Northern War. | [31][48] | |

| Kontor | |

|

|

15th century | Skåne was Danish until ceded to Sweden by the 1658 Treaty of Roskilde, during the Second Northern War. | [31][48] | |

| Kontor | |

|

|

1441 | In 1398 traders guild with close ties to Hanseatic league appeared in Kaunas. Treaty with Hanseatic league was signed in 1441. Main office was located in House of Perkūnas from 1441 till 1532. | [24][31][48] | |

| Kontor | |

|

|

In the 12th and 13th centuries, Pskov adhered to the Novgorod Republic. It was captured by the Teutonic Order in 1241 and liberated by a Lithuanian prince, becoming a de facto sovereign republic by the 14th century. | [31][48] | ||

| Kontor | |

|

|

Polotsk was an autonomous principality of Kievan Rus' until gaining its independence in 1021. From 1240, it became a vassal of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, being fully integrated into the Grand Duchy in 1307. | [31][48] |

Ports with Hansa trading posts

- Berwick-upon-Tweed

- Bristol[31]

- Boston[31][37][48][53]:95

- Damme[31]

- Leith[31][48]

- Hull[31][48]

- Newcastle[31][48]

- Great Yarmouth[31][48]

- York[31][48]

Other cities with a Hansa community

- Aberdeen[54]

- Åbo (Turku)[48]

- Arnhem[50]:432;[55]

- Avaldsnes[37][52]

- Bolsward[34][56]

- Bordeaux[48]

- Brae[48]

- Doesburg[49][50]:433

- Fellin (Viljandi)[24][35]

- Goldingen (Kuldīga)[24]

- Göttingen[25][34][35][57]

- Grindavík[48]

- Grundarfjörður[48]

- Gunnister[48][52][58]

- Haapsalu[24]

- Hafnarfjörður[37][48][59]

- Hamelin[35]

- Hanover[25][34][35]

- Harlingen[citation needed]

- Haroldswick[48]

- Hasselt[25][33][49]

- Hattem[33][49]

- Herford[32]:82;[33][34][35][53]:391

- Hildesheim[25][34][35]

- Hindeloopen (Hylpen)[50]:397;[60]

- Kalmar[33][61]

- Kokenhusen (Koknese)[24][33][35][62][63][64]

- á Krambatangi[37][52]

- Kumbaravogur[65]

- Kulm (Chełmno)[25][33][35]

- Lemgo[25][33][34][35]

- Lemsal (Limbaži)[24][33][35]

- Lippe[25][34]

- Lunna Wick[48]

- Minden[25][33][34][35]

- Naples[61]

- Nantes[48]

- Narva[24][48]

- Nijmegen[33][34][37]

- Nordhausen[25][33]

- Nyborg[48]

- Nyköping[33]

- Oldenzaal[33]

- Paderborn[25][33][35]

- Pernau (Pärnu)[24][25][33][35]

- Roermond[citation needed]

- Roop (Straupe)[24]

- Scalloway

- Smolensk

- Stargard (Stargard Szczeciński)[25][31][33][35][41]:476

- Stavoren (Starum)[50]:398

- Tórshavn[37][48]

- Trondheim[52]

- Tver

- Venlo

- Vilnius[24][48]

- Walk (Valka)[24]

- Weißenstein (Paide)[24]

- Wenden (Cēsis)[24][33][35][47]:60

- Wesel[33][34]

- Wesenberg (Rakvere)[24]

- Windau (Ventspils)[24][33]

- Wolmar (Valmiera)[24][33][35]

- Zutphen[25][33][34][49][50]:433

- Zwolle[25][33][34][49][50]:433, 439

Modern "City League The HANSE"

In 1980, former Hanseatic League members established a "new Hanse" in Zwolle, the "City League The HANSE". This league is open to all former Hanseatic League members and cities that once hosted a Hanseatic kontor. The latter include twelve Russian cities, most notably Novgorod, which was a major Russian trade partner of the Hansa in the Middle Ages. The "new Hanse" fosters and develops business links, tourism and cultural exchange.[66]

The headquarters of the New Hansa is in Lübeck, Germany. The current President of the Hanseatic League of New Time is Bernd Saxe, Mayor of Lübeck.[66]

Each year one of the member cities of the New Hansa hosts the Hanseatic Days of New Time international festival.

In 2006 King's Lynn became the first English member of the newly formed modern Hanseatic League.[67] Hull also joined and Boston, Lincolnshire was considering an application in early 2013.

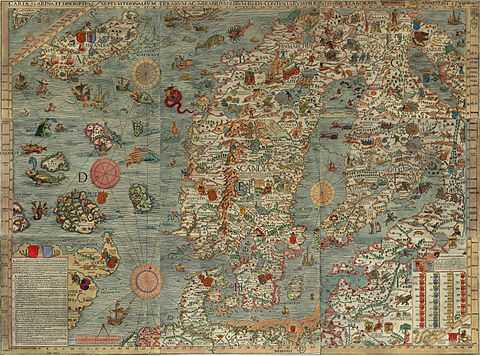

Historical maps

-

Europe in 1097

-

Europe in 1430

-

Europe in 1470

-

Carta marina of the Baltic Sea region (1539)

See also

- Company of Merchant Adventurers of London

- Hanseatic Cross

- Hanseatic Days of New Time

- Hanseatic flags

- Hanseatic Museum and Schøtstuene

- List of ships of the Hanseatic League

- Lufthansa

- Naval history

- Thalassocracy

- The Patrician

Notes

- ↑ Hansen, Mogens Herman (2000). A comparative study of thirty city-state cultures: an investigation. Royal Danish Academy of Sciences & Letters: Copenhagen Polis Centre (Historisk-filosofiske Skrifter 21). p. 305.

- ↑ Popescu, Mircea (2011). Dezagregarea Increderii. Polimedia SRL: Trilema. p. 1.

- ↑ The Cronicle of the Hanseatic League

- ↑ Justyna Wubs-Mrozewicz, Traders, ties and tensions: the interactions of Lübeckers, Overijsslers and Hollanders in Late Medieval Bergen, Uitgeverij Verloren, 2008 p. 111

- ↑ Translation of the grant of privileges to merchants in 1229: "Medieval Sourcebook: Privileges Granted to German Merchants at Novgorod, 1229". Fordham.edu. Retrieved 20 July 2009.

- ↑ Atatüre, Süha (2008). "The Historical Roots of European Union: Integration, Characteristics, and Responsibilities for the 21st Century" (PDF). European Journal of Social Sciences (Eurojournal) 7 (2). Retrieved 26 July 2009.

- ↑ "Medieval Sourcebook: Translated from 'History van Groningen'". Wolters Noordhoff en Bouma's Boekhuis, Groningen 1981. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- ↑ Braudel, Fernand (17 January 2002). The Perspective of the World. Volume 3: Civilization and Capitalism, 15th–18th century. Phoenix Press. ISBN 1-84212-289-4.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Frederick Engels "The Peasant War in Germany" contained in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 10 (International Publishers: New York, 1978) p. 400.

- ↑ Pulsiano, Phillip; Kirsten Wolf (1993). Medieval Scandinavia: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. p. 265. ISBN 0-8240-4787-7.

- ↑ Stearns, Peter N; William Leonard Langer (2001). The Encyclopedia of World History: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern, Chronologically Arranged. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 265. ISBN 0-395-65237-5.

- ↑ MacKay, Angus; David Ditchburn (1997). Atlas of Medieval Europe. Routledge. p. 171. ISBN 0-415-01923-0.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Dollinger, Philippe (2000). The German Hansa. Routledge. pp. 341–3. ISBN 978-0-415-19073-2. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Blumówna, Helena. Kraków jego dzieje i sztuka: Praca zbiorowa [Krakow's history and art: Collective work]. Katowice: 1966. p. 93.

- ↑ Davies, Norman (1982). God's playground. A history of Poland, Volume 1: The Origins to 1795. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-925339-5.

- ↑ "Agreement of the Hanseatic League at Lübeck, 1557". Baltic Connections. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Willson, David Harris (1972). A History of England. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

- ↑ hansa.html

- ↑ GermanFoods.org – Bremen, Hamburg and Luebeck: Culinary Treasures From The Hanseatic Cities

- ↑ "Guide to Lübeck". Europe à la Carte. Retrieved 20 July 2009.

- ↑ "Travel to the Baltic Hansa". Europa Russia.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Hammel-Kiesow, Rolf (2008). Die Hanse (in German). Beck. ISBN 3-406-58352-0.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Pfeiffer, Hermannus (2009). Seemacht Deutschland. Die Hanse, Kaiser Wilhelm II. und der neue Maritime Komplex (in German). Ch. Links Verlag. p. 55. ISBN 3-86153-513-0.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 24.5 24.6 24.7 24.8 24.9 24.10 24.11 24.12 24.13 24.14 24.15 24.16 24.17 24.18 Mills, Jennifer (May 1998). "The Hanseatic League in the Eastern Baltic". Encyclopedia of Baltic History (group research project) . University of Washington.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 25.5 25.6 25.7 25.8 25.9 25.10 25.11 25.12 25.13 25.14 25.15 25.16 25.17 25.18 25.19 25.20 25.21 25.22 25.23 25.24 25.25 25.26 25.27 25.28 25.29 25.30 25.31 25.32 25.33 25.34 25.35 25.36 25.37 25.38 25.39 25.40 25.41 25.42 25.43 25.44 25.45 25.46 25.47 25.48 Falke, Dr Johannes (1863). Die Hansa als deutsche See- und Handelsmacht [The Hansa as a German maritime and trading power]. Berlin: F Henschel. pp. 62–64.

- ↑ Distler, Eva-Marie (2006). Städtebünde im deutschen Spätmittelalter. Eine rechtshistorische Untersuchung zu Begriff, Verfassung und Funktion (in German). Vittorio Klostermann. pp. 55–57. ISBN 3-465-04001-5.

- ↑ Fritze, Konrad et al. (1985). Die Geschichte der Hanse (in German). p. 217.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 28.4 28.5 28.6 28.7 28.8 28.9 28.10 28.11 28.12 28.13 28.14 28.15 28.16 28.17 Natkiel, Richard (1989). Atlas of Maritime History. Smithmark Publishing. p. 33. ISBN 0-8317-0485-3.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 29.5 29.6 29.7 29.8 29.9 29.10 29.11 29.12 29.13 29.14 Michael Keating,Regions and regionalism in Europe, 2004, Edward Elgar Publishing, pages 47 and 120

- ↑ Reibstein, Ernst. "Das Völkerrecht der deutschen Hanse" (PDF) (in German). Max-Planck-Institut für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht. pp. 56–57 (print), pp. 19–20 in pdf numbering. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 31.4 31.5 31.6 31.7 31.8 31.9 31.10 31.11 31.12 31.13 31.14 31.15 31.16 31.17 31.18 31.19 31.20 31.21 31.22 31.23 31.24 31.25 31.26 31.27 31.28 31.29 31.30 31.31 31.32 31.33 31.34 31.35 31.36 31.37 31.38 31.39 31.40 31.41 31.42 31.43 31.44 31.45 31.46 31.47 31.48 31.49 31.50 31.51 31.52 Jotischky, Andrew; Caroline Hull (2005). The Penguin Historical Atlas of the Medieval World. Penguin Books. pp. 122–23. ISBN 978-0-14-101449-4.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 32.4 32.5 32.6 32.7 32.8 32.9 32.10 32.11 32.12 32.13 32.14 32.15 32.16 32.17 Holborn, Hajo (1982). A History of Modern Germany: The Reformation. Princeton University Press. pp. 32, 74, 80–82. ISBN 0-691-00795-0.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 33.4 33.5 33.6 33.7 33.8 33.9 33.10 33.11 33.12 33.13 33.14 33.15 33.16 33.17 33.18 33.19 33.20 33.21 33.22 33.23 33.24 33.25 33.26 33.27 33.28 33.29 33.30 33.31 33.32 33.33 33.34 33.35 33.36 33.37 33.38 33.39 33.40 33.41 33.42 33.43 33.44 33.45 33.46 33.47 33.48 33.49 33.50 33.51 33.52 33.53 33.54 33.55 33.56 33.57 33.58 33.59 Dollinger, Philippe (2000). The German Hansa. Stanford University Press. pp. ix–x. ISBN 0-8047-0742-1. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 34.4 34.5 34.6 34.7 34.8 34.9 34.10 34.11 34.12 34.13 34.14 34.15 34.16 34.17 34.18 34.19 34.20 34.21 34.22 34.23 34.24 34.25 34.26 34.27 34.28 34.29 34.30 34.31 34.32 34.33 Barthold, Dr Friedrich Wilhelm (1862). Geschichte der Deutschen Hanse [History of the German Hansa]. Leizig: TD Weigel. pp. 35 and 496–7.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 35.4 35.5 35.6 35.7 35.8 35.9 35.10 35.11 35.12 35.13 35.14 35.15 35.16 35.17 35.18 35.19 35.20 35.21 35.22 35.23 35.24 35.25 35.26 35.27 35.28 35.29 35.30 35.31 35.32 35.33 35.34 35.35 35.36 35.37 35.38 Schäfer, D (2010). Die deutsche Hanse [The German Hanseatic League]. Reprint-Verlag-Leipzig. pp. page 37. ISBN 978-3-8262-1933-7.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 36.4 36.5 36.6 Wernicke, Horst (2007). "Die Hansestädte an der Oder". In Schlögel, Karl; Halicka, Beata. Oder-Odra. Blicke auf einen europäischen Strom (in German). Lang. pp. 137–48; here p. 142. ISBN 3-631-56149-0.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 37.4 37.5 37.6 37.7 37.8 37.9 37.10 37.11 37.12 37.13 Mehler, Natascha (2009). "The Perception and Interpretation of Hanseatic Material Culture in the North Atlantic: Problems and Suggestions" (PDF). Journal of the North Atlantic (Special Volume 1: Archaeologies of the Early Modern North Atlantic): 89–108.

- ↑ "Stralsund". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 39.4 39.5 Buchholz, Werner et al. (1999). Pommern (in German). Siedler. p. 120. ISBN 3-88680-272-8.

- ↑ (Swedish) "Varför ruinerades Visby" [Why is Visby ruined]. Goteinfo.com. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 41.3 Bedford, Neil (2008). Poland. Lonely Planet. pp. 403, 436, 452 and 476. ISBN 978-1-74104-479-9.

- ↑ Alma Mater (109). Kraków: Jagiellonian University. 2008. p. 6.

- ↑ Carter, Francis W. (1994). Trade and urban development in Poland. An economic geography of Cracow, from its origins to 1795, Volume 20. Cambridge studies in historical geography. Cambridge University Press. pp. 70–71, 100–02. ISBN 0-521-41239-0.

- ↑ Jelicz, Antonina (1966). Życie codzienne w średniowiecznym Krakowie: wiek XIII–XV [Everyday life in medieval Krakow: 13th–15th century]. Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy.

- ↑ Gilewska-Dubis, Janina (2000). Życie codzienne mieszczan wrocławskich w dobie średniowiecza [Everyday life of citizens of Wrocław during medieval times]. Wydawnictwo Dolnośląskie. p. 160.

- ↑ Buśko, Cezary; Włodzimierz Suleja, Teresa Kulak (2001). Historia Wrocławia: Od pradziejów do końca czasów habsburskich [Wrocław History: From Prehistory to the end of the Habsburg era]. Wydawnictwo Dolnośląskie. p. 152.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Turnbull, Stephen R (2004). Crusader castles of the Teutonic Knights: The stone castles of Latvia and Estonia 1185–1560. Osprey Publishing. pp. pages 20 and 60. ISBN 978-1-84176-712-3.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 48.3 48.4 48.5 48.6 48.7 48.8 48.9 48.10 48.11 48.12 48.13 48.14 48.15 48.16 48.17 48.18 48.19 48.20 48.21 48.22 48.23 48.24 48.25 48.26 48.27 48.28 48.29 48.30 48.31 48.32 Mehler, Natascha (2011). "Hansefahrer im hohen Norden" (PDF). epoc (2): 16–25, particularly 20 and 21.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 49.3 49.4 49.5 49.6 ver Berkmoes, Ryan; Karla Zimmerman (2010). The Netherlands. Lonely Planet. pp. 255. ISBN 978-1-74104-925-1.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 50.3 50.4 50.5 50.6 50.7 50.8 McDonald, George (2009). Frommer's Belgium, Holland & Luxembourg, 11th Edition. Frommers. pp. pages 134, 176, 397, 432–38. ISBN 978-0-470-38227-1.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Hanseatic League". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Hanseatic League". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press - ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 52.3 52.4 Mehler, Natascha (April 2009). "HANSA: The Hanseatic Expansion in the North Atlantic". University of Vienna. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 53.3 Ward, Adolphus William. Collected Papers Historical, Literary, Travel and Miscellaneous. pp. pages 95 and 391.

- ↑ Mitchell, Alex. "The Old Burghs Of Aberdeen". Aberdeen Civic Society. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- ↑ Merriam-Webster, Inc (1997). Merriam-Webster's geographical dictionary. Merriam-Webster, Inc. pp. 74–75. ISBN 978-0-87779-546-9.

- ↑ Miruß, Alexander (1838). Das See-Recht und die Fluß-Schifffahrt nach den Preußischen Gesetzen. Leipzig: JC Hinrichsschen Buchhandlung. p. 17. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ↑ "Göttingen". Encyclopædia Brittanica. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ↑ Gardiner, Mark; Natascha Mehler (2010). "The Hanseatic trading site at Gunnister Voe, Shetland" (PDF). Post-Medieval Archaeology 44 (2): 347–49.

- ↑ Bjarnadóttir, Kristín (2006). "Mathematical Education in Iceland in Historical Context" (PDF). Roskilde University. p. 52. ISSN 0106-6242. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ↑ Wild, Albert (1862). Die Niederlande: ihre Vergangenheit und Gegenwart, Volume 2 [The Netherlands: its past and present, Volume 2]. Wigand. pp. page 250.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 Dollinger, Philippe (2000). The German Hansa. Routledge. pp. pages 128 and 352. ISBN 978-0-415-19073-2.

- ↑ "History of Koknese". Koknese official website. 10 January 2011. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ "Collector Coin Koknese". National Bank of Latvia. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ Könnecke, Jochen; Vladislav Rubzov (2005). Lettland [Lithuania]. DuMont Reiseverlag. pp. pages 23, 26–7 and 161. ISBN 978-3-7701-6386-1.

- ↑ Mehler, Natascha (October 2010). "The Operation of International Trade in Iceland and Shetland (c. 1400–1700)". University of Vienna. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 "City League The HANSE".

- ↑ "King's Lynn Hanse Festival 2009". Borough Council of King's Lynn and West Norfolk. Retrieved 23 August 2010.

References

- Dollinger, P (2000). The German Hansa. Routledge. pp. 341–3. ISBN 978-0-415-19073-2. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- Nash, Elizabeth Gee (1929). The Hansa. ISBN 1-56619-867-4.

- Schulte Beerbühl, Margrit (2012). Networks of the Hanseatic League. Mainz: Institute of European History. Retrieved 24 January 2012.

- Thompson, James Westfall (1931). Economic and Social History of Europe in the Later Middle Ages (1300–1530). pp. 146–79. ASIN B000NX1CE2.

External links

| Find more about Hanseatic League at Wikipedia's sister projects | |

| |

Definitions and translations from Wiktionary |

| |

Media from Commons |

| |

Quotations from Wikiquote |

| |

Source texts from Wikisource |

| |

Textbooks from Wikibooks |

| |

Learning resources from Wikiversity |

- 29th International Hansa Days in Novgorod

- 30th International Hansa Days 2010 in Parnu-Estonia

- NPG Social & Cultural Struggle for an Hanseatic Revival

- Chronology of the Hanseatic League

- Hanseatic Cities in The Netherlands

- Hanseatic League Historical Re-enactors

- Hanseatic Towns Network

- Hanseatic League related sources in the German Wikisource

- Colchester: a Hanseatic port—Gresham

- The Lost Port of Sutton: Maritime trade

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||