Hamon (swordsmithing)

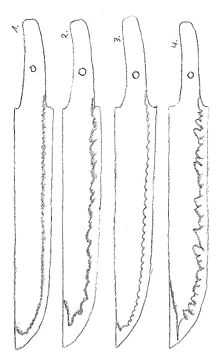

In swordsmithing, hamon (刃文 hamon) (from Japanese, literally "blade pattern") is a visual effect created on the blade by the hardening process. The hamon is the outline of the hardened zone (yakiba) which contains the cutting edge (ha). Blades made in this manner are known as differentially hardened, with a harder cutting edge than spine, or "mune" (for example: mune 40 HRC vs ha 58 HRC). This difference in hardness results from clay being applied on the blade prior to the cooling process (quenching). Less or no clay allows the ha to cool faster, making it harder but more brittle, while more clay allows the mune to cool slower and retain its resilience.[1]

The hamon outlines the transition between the region of harder martensitic steel at the blade's edge and the softer pearlitic steel at the center and back of the sword. This difference in hardness is the objective of the process; the appearance is purely a side effect. However, the aesthetic qualities of the hamon are quite valuable—not only as proof of the differential-hardening treatment but also in its artistic value—and the patterns can be quite complex.

Many modern reproductions do not have natural hamon because they are thoroughly hardened monosteel; the appearance of a hamon is reproduced via various processes such as acid etching, sandblasting, or more crude ones such as wire brushing. Some modern reproductions with natural hamon are also subjected to acid etching to enhance that hamon's prominence. A true hamon can be easily discerned by the presence of a "nioi," which is a bright, speckled line a few millimeters wide, following the length of the hamon. The nioi is typically best viewed at long angles, and cannot be faked with etching or other methods. When viewed through a magnifying lens, the nioi appears as a sparkly line, being made up of many bright martensite grains, which are surrounded by darker, softer pearlite.[1]

Origins

According to legend, Amakuni Yasutsuna developed the process of differentially hardening the blades around the 8th century AD. The emperor was returning from battle with his soldiers when Yasutsuna noticed that half of the swords were broken:

"Amakuni and his son, Amakura, gathered up the broken blades and examined them. They were determined to create a blade that would not break in combat and locked themselves away in seclusion for 30 days. When they reappeared, they carried with them the curved blade. The following spring there was another war. Again the soldiers returned, only this time all the swords were intact and the emperor smiled on Amakuni."[2]

Although impossible to ascertain who actually invented the technique, surviving blades by Yasutsuna from around 749–811 AD suggest that at the very least Yasutsuna helped establish the tradition of differentially hardening the blades.[2]