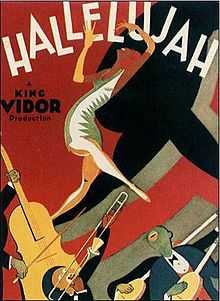

Hallelujah! (film)

| Hallelujah | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | King Vidor |

| Produced by |

King Vidor Irving Thalberg |

| Written by |

King Vidor Ransom Rideout Richard Schayer Wanda Tuchock |

| Starring |

Daniel L. Haynes Nina Mae McKinney William E. Fountaine Harry Gray Fannie Belle de Knight |

| Music by | Irving Berlin |

| Cinematography | Gordon Avil |

| Editing by |

Anson Stevenson Hugh Wynn |

| Distributed by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

| Release dates | August 20, 1929 |

| Running time | 109 minutes (original release), 100 minutes (1939 re-issue, the version available on DVD) |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Hallelujah (1929) is a Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer musical directed by King Vidor, and starring Daniel L. Haynes and the then unknown Nina Mae McKinney.

Filmed in Tennessee and Arkansas and chronicling the troubled quest of a sharecropper, Zeke Johnson (Haynes), and his relationship with the seductive Chick (McKinney), Hallelujah was one of the first all-black films by a major studio. It was intended for a general audience and was considered so risky a venture by MGM that they required King Vidor to invest his own salary in the production. Vidor's vision was to attempt to present a relatively non-stereotyped view of African-American life.

Hallelujah was King Vidor's first sound film, and combined sound recorded on location and sound recorded post-production in Hollywood.[1] King Vidor was nominated for a Best Director Oscar for the film.

In 2008, Hallelujah was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant."

Plot summary

Sharecroppers Zeke and Spunk Johnson sell their part of the cotton crop for $100. Cheated out of the money by Zeke's girlfriend Chick (sixteen-year-old Nina Mae McKinney, in possibly her greatest role), in collusion with her gambling-hustler friends, Spunk is murdered in the ensuing brawl. Zeke runs away and reforms his life, becoming a minister.

Sometime later, he returns and preaches a rousing revival. Now engaged to a virtuous maiden named Missy (Victoria Spivey), he finds that Chick is still interested in him. She asks for baptism but is clearly not truly repentant. Tragically, Zeke throws away his new life for her. The film then cuts to Zeke's new life; he is working at a log mill and is married to Chick, who is secretly cheating on him with her old flame, Hot Shot (William Fountaine).

When Chick and Hot Shot decide to cut and run just as Zeke finds out about the affair, Zeke follows after them. The carriage carrying both Hot Shot and Chick overturns, and Zeke catches up to them. Holding her in his arms, he watches Chick die as she apologizes to him for being unable to change her ways. Zeke then chases Hot Shot on foot. He stalks slowly through the woods and swamp while Hot Shot tries to run but continues to stumble until Zeke finally kills him. The film ends with Zeke returning to his family at the cotton crop after serving time in prison. His family is more than happy to welcome him back into the flock.

The Music

The film gives, in some sections, a remarkably authentic representation of black entertainment and religious music in the 1920s, which no other film achieves. Unfortunately some of the sequences are rather Europeanised and over-arranged. For example, the outdoor revival meeting, with the preacher singing and acting out the 'Train to hell', is entirely authentic in style until the end, where he launches into the popular song 'Waiting at the End of the Road'. Similarly, an outdoor group of workers singing near the beginning of the film are saddled with a choral arrangement of 'Way Down upon the Swanee River' (written by Stephen Foster, who never went anywhere near the South) - no black workers would sing that!.

The best sequence (and one which is of vital importance in the history of classic jazz) is in the dancehall, where Nina Mae McKinney gives a stunning performance of Irving Berlin's 'Swanee Shuffle' - just the right sort of popular song; although actually filmed in a New York studio using black actors, the sequence gives an accurate representation of a low-life black dance-hall - part of the roots of classic jazz. Nothing else on film comes near this: most Hollywood films sanitized black music out of all recognition; and later, in the 1930s, when black artists began to show their real styles, jazz had moved on to become more sophisticated and the whole style of behaviour had changed. All this makes the film a unique document: and it's worth adding that the soundtrack throughout the film is a remarkable achievement, given the primitive equipment available at the time, with a much wider range of editing and mixing techniques than is generally thought to have been used so early on in talkies.

Reception

Hallelujah was commercially and critically successful. Photoplay praised the film for its depiction of African Americans and commented on the cast: "Every member of of Vidor's cast is excellent. Although none of them ever worked before a camera or a microphone before, they give unstudied and remarkably spontaneous performances. That speaks a lot for Vidor's direction."[2]

References

- ↑ Donald Crafton, The Talkies: American Cinema's Transition to Sound, 1926-1931 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999) p. 405. ISBN 0-684-19585-2

- ↑ Kreuger, Miles ed. The Movie Musical from Vitaphone to 42nd Street as Reported in a Great Fan Magazine (New York: Dover Publications) p 70. ISBN 0-486-23154-2

External links

- Hallelujah at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Hallelujah at the Internet Movie Database

- Hallelujah at allmovie

- A review on barnesandnoble.com

- Classic Black Films Stand as History, Art from NPR's "All Things Considered", first broadcast January 13, 2006.

- "Spotlight: Hallelujah!" at Turner Classic Movies

- "King Vidor's Hallelujah" at the Museum of Modern Art

| ||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||