Halcott Mountain

| Halcott Mountain | |

|---|---|

Halcott from Belleayre Ski Center to the south | |

| Elevation | 3520+ ft (1073 m)+ NGVD 29[1] |

| Prominence | 700 ft (213 m)[1] |

| Listing | Catskill High Peaks #32 |

| Location | |

| Location | Lexington, NY, USA |

| Range | Catskill Mountains |

| Coordinates | 42°10′48″N 74°26′17″W / 42.1800882°N 74.4379281°WCoordinates: 42°10′48″N 74°26′17″W / 42.1800882°N 74.4379281°W[2] |

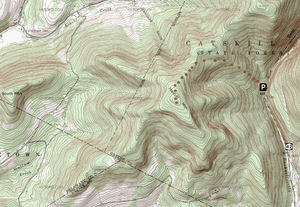

| Topo map | USGS West Kill |

| Geology | |

| Type | Dissected plateau |

| Age of rock | 250-350 mya |

| Climbing | |

| Easiest route | Hike up east slope from NY 42 to summit ridge |

Halcott Mountain is one of the Catskill Mountains of the U.S. state of New York. It is mostly located in Greene County, with some of its lower slopes in Delaware and Ulster counties. Its exact summit elevation has not been officially determined, but the highest contour line on the mountain is 3,520 feet (1,070 m). It is one of the peaks on the divide between the Delaware and Hudson watersheds.

As one of the Catskill High Peaks above 3,500 feet (1,100 m) in elevation, a successful ascent of Halcott is required for peakbaggers seeking to join the Catskill Mountain 3500 Club. It is on public land, part of the Catskill Park Forest Preserve, but has no trail. Hikers bushwhack through the relatively open woods to sign the canister at the summit and prove their climb. It is considered one of the easiest of the 13 trailless High Peaks.[3]

Geography

The mountain spreads over a wide area. Most of it is located in the Greene County town of Lexington. Some of its lower eastern slopes are in Halcott to the west, and the tripoint of the three counties is on one of its southern ridges, putting those points south of the Greene County line in either the Ulster County town of Shandaken or Delaware County's Middletown.[4] Most of the land on the mountain in Greene County is part of the 4,760-acre (1,930 ha) Halcott Mountain Wild Forest, managed by the state Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC).[5] The lower eastern slope is outside the Catskill Park Blue Line, and private tracts are at the base of its slopes in the other two counties. The nearest settlements are the small communities of Fleischmanns and Pine Hill a short distance to the southwest and south and smaller West Kill further away to the north.[6]

On three sides Halcott's slopes are defined by alternating creek valleys and ridges that divide them. The eastern slopes are steeper, falling 1,700 feet (520 m) into Deep Notch, the pass between it and Mount Sherrill to the east, traversed by state highway NY 42. The south slopes lead more gradually, with a few steep sections, to the Birch Creek valley. On the southwest the ridge with the tripoint continues to a 1,500 feet (460 m) height of land between Halcott and 2,456-foot (749 m) Monka Hill, site of the former Grand Hotel. Another, more westerly ridge reaches a 2,420-foot (740 m) col between Halcott and one of the several South Mountains in the Catskills.[4] Estimates of the mountain's actual summit elevation range to the higher end of the 20-foot (6 m) contour interval, to as high as 3,541 feet (1,079 m).[5][7]

The west slopes make a very gentle grade to the Elk Creek valley, with some steep portions on the northwest at the headwall of Hemlock Gully. To the north a ridge descends gently to 2,990 feet (910 m) before rising again to the 3,408-foot (1,039 m) peak officially unnamed[4] but known as either Northeast Halcott or Sleeping Lion.[8]

Bushnellsville Creek and an unnamed tributary drain the east side of the mountain, both feeding into Esopus Creek, whose waters are impounded downstream for New York City's Ashokan Reservoir before draining into the Hudson. Bushnellsville and its tributary both form scenic waterfalls near the bottom of Halcott's slopes near Route 42. Birch Creek, which rises in the valleys south of Halcott, drains into the Esopus at Big Indian. Elk and Emory creeks (the former via Vly Creek) both drain into Bush Kill, which in turn empties into the East Branch of the Delaware near Arkville.

Geology

Like the Catskills as a whole, a dissected plateau, Halcott was formed not through the upthrust of rock layers but by the gradual erosion of stream valleys in an uplifted region about 350 mya. Its rock layers and bedrock are primarily Devonian and Silurian shale and sandstone.[9] Later glaciation, primarily the Illinois and Wisconsin periods, shaped the slopes of the mountain, smoothing its slopes on the west when the ice was covering it and steepening the east slopes through erosion when the meltwater burst through Deep Notch.[10]

Its soils are part of the Halcott-Vly association, reddish silt loams with a large concentration of fragmented rock. They are shallow and extremely acidic with low water capacity. As a result they are erosion-prone and rock outcrops are frequent on the mountain slopes.[10]

Flora and fauna

Halcott is extensively forested, primarily in mature northern hardwoods (beech, birch and maple), with some small Norway spruce and red pine plantations at lower elevations and scattered stands of hemlock left over from the era when those trees were heavily harvested for their tannin-rich bark.[11] There is also a stand of paper birch on the southwestern slope of the mountain, as a result of past human disturbance.[12] A 1908 forest fire resulted in a stand of yellow birch in the upper reaches of Hemlock Gully.[13]

The slopes of the mountain were logged to some degree up to an average elevation of 3,150 feet (960 m), leaving a first-growth area of roughly 0.6 square miles (1.6 km2) on and below the summit. Trees in this area are stunted and twisted by the wind and weather exposure. There are no boreal evergreens, such as balsam fir and red spruce, as found on many other of the other Catskill High Peaks at these elevations.[14] Some boreal herbs, such as wood sorrel, have remained at those elevations.[15]

DEC estimates that there are 49 mammal species, 20 amphibians, 13 reptiles and 71 birds that live on the slopes and ridges. Among the more visible species are big game such as white-tailed deer and black bear. Fishers were reintroduced to the Catskills in the late 1970s; a few are taken by trappers every season. Among bird species, the bald eagles, red-throated hawk and the eastern bluebird (New York's state bird), are the first of which are considered threatened and the latter of concern, are present.[16]

History

Halcott, like the town in which it is partially located, took its name from an early landowner. The west slopes of the mountain were cleared for agriculture to well over 2,000 feet (600 m) in the early days of settlement; the steeper slopes on the east side were generally not cleared much above the road. The exception to that was one field northwest of the former hamlet of Bushnellsville, which went up to 2,360 feet (720 m). Old stone walls and foundations remain in the forest on the mountain's lower slopes.[17]

Between the fields and the first-growth forest on the summit is the forestry belt, where trees were cut by local farmers as firewood and hemlocks were harvested so that the tanning in their bark could be used to tan leather, a major regional industry that died out in the late 19th century when most of the accessible groves in the Catskills had been peeled and a synthetic process for making tannin was developed.[18]

After the barkpeeling industry faded, the state created the Forest Preserve in 1885 to protect what was left by mandating that all the land owned by the state in what is now the Catskill Park be kept "forever wild" and not sold, leased or otherwise transferred. In 1894 that section was written into the state constitution.[17] A few years later the state bought the lands around Halcott's summit. The west slope was acquired in 1934, with the state land holding reaching its current size by 1957.[18]

DEC has done little management of the land, since no trail has ever been cut on the mountain and it has not needed to. The area is designated as a Wild Forest, allowing in theory for some intensive use, but that is only because it is too small to be a wilderness area. Under its own guidelines, land above 2,700 feet (820 m) in wild forests is to be treated as wilderness. The peak has been on the 3500 Club's list since its founding in 1962, and is also popular with hunters as well.[19] In its 2001 unit management plan, DEC raised the possibility of building a trail to connect with another possible westward extension of the Devil's Path over North Dome and Mount Sherrill in the West Kill Wilderness Area to the east,[20] but so far that plan has gone no further.

Access

The most commonly used approach to the summit, since it takes place entirely on public land, starts at the rough parking area on the west side of Route 42 south of Deep Notch, right next to the waterfall on the northern tributary of Bushnellsville Creek, at an elevation of roughly 1,800 feet (550 m). From here hikers generally follow the ridge to the west, trending a bit southward.[3][7][21] Upon gaining the ridge at 3,000 feet (910 m), they follow it south up mostly gentle slopes to the mountain's summit, where a rough use path runs north-south to the canister, mounted on a cherry tree at the southern end. It is a 1,720-foot (520 m) ascent via this route, with the round trip covering approximately six miles (9.6 km).[7]

There are no views from the summit when the trees are in leaf,[3] and in other seasons those views to the south are partially obstructed by other surrounding trees. Views may be available from the southern slopes at the top of steep drops.[3][6][21]

Access from the south and west follows gentler slopes but requires gaining permission from landowners to cross private landholdings at the mountain's base.[3][7][21] From the north it is possible to hike entirely on public land as well via a long approach across Northeast Halcott.

See also

- List of mountains in New York

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Halcott Mountain, New York". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved 2010-05-17.

- ↑ "Halcott Mountain". Geographic Names Information System, U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 2010-05-17.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 "Halcott Mountain 3537'". Catskill Mountain 3500 Club. 2007–2010. Retrieved February 1, 2010.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 United States Geological Survey. West Kill Quadrangle — New York — Greene Co. (Map). 1:24,000. 7.5 minute series. http://www.topoquest.com/map.php?lat=42.18038&lon=-74.43792&datum=nad83&zoom=8&map=auto&coord=d&mode=zoomout&size=m. Retrieved 2010-01-31.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Halcott Mountain Wild Forest, Unit Management Plan". New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC). September 2001. p. 6. Retrieved January 31, 2010.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 New York – New Jersey Trail Conference (2005). Central Catskill Trails (Map). 1:63,360. Cartography by Koch, Ted and Benjamin, Sheryl (8th ed.). Section 3I–J, 4I–J. ISBN 1-880775-46-8.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Wadsworth, Bruce; members of the Adirondack Mountain Club Schenectady chapter (1988). Guide to Catskill Trails (2nd, with revisions ed.). Lake George, NY: Adirondack Mountain Club. pp. 277–78. ISBN 0-935272-71-2. "The usual starting point on state land is an unmarked parking area on the W side of NY 42, 2.4 mi south of the hamlet of West Kill"

- ↑ Kudish, Michael (2000). The Catskill Forest: A History. Fleischmanns, NY: Purple Mountain Press. p. 125. ISBN 1-930098-02-2. "... Northeast Halcott, also known as Sleeping Lion (3,407 feet) ..."

- ↑ Titus, Robert (1993). The Catskills: A Geological Guide. Fleischmanns, NY: Purple Mountain Press. pp. 22–34. ISBN 0-935796-40-1.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 DEC, 7.

- ↑ DEC, 8.

- ↑ Kudish, 25.

- ↑ Kudish, 128.

- ↑ Kudish, 126.

- ↑ Kudish, 29.

- ↑ DEC, 9.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 DEC, 10.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Kudish, 126–27.

- ↑ DEC, 11.

- ↑ DEC, 13.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 McAllister, Lee; Ochman, Myron (1989). Hiking the Catskills. New York: New York-New Jersey Trail Conference. pp. 276–77. ISBN 0-9603966-6-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Halcott Mountain. |

- "Halcott Mountain 3537'". Catskill 3500 Club. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||