Hadewijch

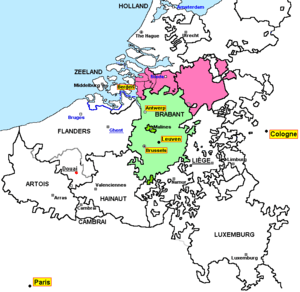

Hadewijch (often referred to as Hadewych, Hadewig, Hadewijch of Antwerp or Hadewijch of Brabant) was a 13th-century poet and mystic, probably living in the Duchy of Brabant, and perhaps in Antwerp.[1][2][3] Most of her extant writings are in a Brabantian form of Middle Dutch. Her writings include visions, prose letters and poetry. The poetry of the mystic would play an important role in the essays, plays and novels of Belgian writer Suzanne Lilar and were one of the most important direct influences on the mystical thought of Blessed John of Ruysbroeck.

Life

No details of her life are known outside the sparse indications in her own writings. Her Letters suggest that she functioned as the head of a beguine house, but that she had experienced opposition that drove her to a wandering life.[4] This evidence, as well as her lack of reference to life in a convent, makes the nineteenth-century theory that she was a nun extremely problematic, and it has been abandoned by modern scholars.[5] She must have come from a wealthy family: her writing demonstrates an expansive knowledge of the literature and theological treatises of several languages, including Latin and French, as well as French courtly poetry, during a time when studying was a luxury only exceptionally granted to women.

Works

Most of her extant writings, none of which survived the Middle Ages as an autograph, are in a Brabantian form of Middle Dutch. Her writings do not appear to have been widely known – they do not appear to have been collected and published until the middle of the fourteenth century, and only five manuscripts survive.[6]

Her writings include poetry, descriptions of her visions, and prose letters. There are two types of poems. Her forty-five Poems in Stanzas (Strophische Gedichten) are lyric poems following the forms and conventions used by the trouvères and minnesingers of her time, but with the theme of worldly courtship replaced by sublimated love to God. The sixteen Poems in Couplets (Mengeldichten) other series of poems are simpler didactical poems in letter format, composed in rhyming couplets, on Christian topics, not all of them considered authentic.

Hadewijch’s Book of Visions (Visioenenboek), the earliest vernacular collection of such revelations, appears to have been composed in the 1240s.[7]

Thirty prose letters also survive.[8]

Influence

| Part of a series on |

| Christian mysticism |

|---|

|

|

Main articles |

|

11th and 12th century |

|

13th and 14th centuries Dominican mysticism Dominic de Guzmán |

|

15th and 16th centuries |

|

20th century Pio of Pietrelcina Maria Valtorta |

|

Contemporary Papal views |

Hadewijch's ideas exerted little impact in their day, until they came to the notice of a later Dutch mystic, Jan van Ruusbroec, who adopted (without mentioning her name) her Trinitarian doctrine and other core ideas. Ruusbroec himself came to be widely translated and read, having a great impact on the wider Catholic tradition. Even though Hadewijch herself has been little read until modern times, her ideas have, indirectly, filtered into wider thought.

The poetry of the mystic Hadewych would play an important role in the essays, plays and novels of Belgian writer Suzanne Lilar.

Notes

- ↑ Also Hadewych/Hadewijch/Hadewig of Brabant. Note that in the modern state of Belgium Antwerp (the city) lies not in Brabant (the Belgian province) but in the province of Antwerp. The "of Brabant" and "of Antwerp" identifications of the 13th century Hadewijch are apparently primarily intended to distinguish her from the 12th-century German prioress Blessed Hadewych. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/07104a.htm]

- ↑ Part of the evidence for her origins lies in the fact that most of the manuscripts containing her work were found near Brussels.

- ↑ The Antwerp connection is mainly based on a later addition to one of the manuscript copies of her works, that was produced several centuries after her death.

- ↑ Letter 29.

- ↑ The 19th century understanding (based exclusively on her visions and poetry) that she would have been a nun, as described for instance in C.P. Serrure (ed.), Vaderlandsch museum voor Nederduitsche letterkunde, oudheid en geschiedenis, II (C. Annoot-Braeckman, Gent 1858), pp. 136-145. That she could be identified with an abbess that presumably died in Aywières (the convent where also Saint Lutgard lived around the same time) in 1248, is considered even more unlikely in recent scholarship. For more on this, see, for instance, the writings by Paul Mommaers mentioned in the references section below.

- ↑ Bernard McGinn, The Flowering of Mysticism, (1998), p200.

- ↑ Bernard McGinn, The Flowering of Mysticism, (1998), p200.

- ↑ Bernard McGinn, The Flowering of Mysticism, (1998), p200.

References

- Hadewijch – Columba Hart (ed. and translator), preface by Paul Mommaers (1980), Hadewijch: The Complete Works, Paulist Press ISBN 0-8091-2297-9

- Hadewijch – Marieke J. E. H. T. van Baest (essay and translations), preface by Edward Schillebeeckx (1998-01-01), Poetry of Hadewijch, Peeters ISBN 90-429-0667-7

- Mommaers, Paul – Elisabeth M. Dutton (transl.) (April 2005), Hadewijch: Writer – Beguine – Love Mystic, Peeters ISBN 90-429-1392-4

- McGinn, Bernard, The Flowering of Mysticism, (1998), pp. 200–244.

External links

Quotations related to Hadewijch at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Hadewijch at Wikiquote- Hadewijch in the Columbia Encyclopedia

- Hadewijch at DBNL (digitale bibliotheek voor Nederlandse letteren) Introductions (most of them in Dutch) and various editions of Hadewijch's writings in Middle Dutch

- James Charlton's Transgressive Saints

- Poetry by Hadewijch in English translation