Gyrator

A gyrator is a passive, linear, lossless, two-port electrical network element proposed in 1948 by Bernard D. H. Tellegen as a hypothetical fifth linear element after the resistor, capacitor, inductor and ideal transformer.[1] Unlike the four conventional elements, the gyrator is non-reciprocal. Gyrators permit network realizations of two-(or-more)-port devices which cannot be realized with just the conventional four elements. In particular, gyrators make possible network realizations of isolators and circulators.[2] Gyrators do not however change the range of one-port devices that can be realized. Although the gyrator was conceived as a fifth linear element, its adoption makes both the ideal transformer and either the capacitor or inductor redundant. Thus the number of necessary linear elements is in fact reduced to three. Circuits that function as gyrators can be built with transistors and op amps using feedback.

An important property of a gyrator is that it inverts the current-voltage characteristic of an electrical component or network. In the case of linear elements, the impedance is also inverted. In other words, a gyrator can make a capacitive circuit behave inductively, a series LC circuit behave like a parallel LC circuit, and so on. It is primarily used in active filter design and miniaturization.

Behaviour

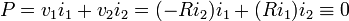

where  is the gyration resistance of the gyrator.

is the gyration resistance of the gyrator.

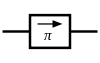

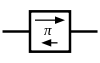

The gyration resistance (or equivalently its reciprocal the gyration conductance) has an associated direction indicated by an arrow on the schematic diagram.[3] By convention, the given gyration resistance or conductance relates the voltage on the port at the head of the arrow to the current at its tail. The voltage at the tail of the arrow is related to the current at its head by minus the stated resistance. Reversing the arrow is equivalent to negating the gyration resistance, or to reversing the polarity of either port.

Although a gyrator is characterized by its resistance value, it is a lossless component. From the governing equations, the instantaneous power into the gyrator is identically zero.

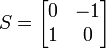

A gyrator is an entirely non-reciprocal device, and hence is represented by antisymmetric impedance and admittance matrices:

which is likewise antisymmetric. This leads to an alternative definition of a gyrator: a device which transmits a signal unchanged in the forward (arrow) direction, but reverses the polarity of the signal travelling in the backward direction (or equivalently,[6] 180° phase-shifts the backward travelling signal[7]). The symbol used to represent a gyrator in one-line diagrams (where a waveguide or transmission line is shown as a single line rather than as a pair of conductors), reflects this one-way phase shift.

As with a quarter wave transformer, if one of port of the gyrator is terminated with a linear load, then the other port presents an impedance inversely proportional to that of the load,

A generalization of the gyrator is conceivable, in which the forward and backward gyration conductances have different magnitudes, so that the admittance matrix is

However this no longer represents a passive device.[8]

Relationship to the ideal transformer

Cascaded gyrators of gyration resistance  and

and  are equivalent to a transformer of turns ratio

are equivalent to a transformer of turns ratio  . Cascading a transformer and a gyrator, or equivalently cascading three gyrators produces a single gyrator of gyration resistance

. Cascading a transformer and a gyrator, or equivalently cascading three gyrators produces a single gyrator of gyration resistance  .

.

From the point of view of network theory, transformers are redundant when gyrators are available. Anything that can be built from resistors, capacitors, inductors, transformers and gyrators, can also be built using just resistors, gyrators and inductors (or capacitors)

Application: a simulated inductor

A gyrator can be used to transform a load capacitance into an inductance. At low frequencies and low powers, the behaviour of the gyrator can be reproduced by a small op-amp circuit. This supplies a means of providing an inductive element in a small electronic circuit or integrated circuit. Before the invention of the transistor, coils of wire with large inductance might be used in electronic filters. An inductor can be replaced by a much smaller assembly containing a capacitor, operational amplifiers or transistors, and resistors. This is especially useful in integrated circuit technology.

Operation

In the circuit shown, one port of the gyrator is between the input terminal and ground, while the other port is terminated with the capacitor. The circuit works by inverting and multiplying the effect of the capacitor in an RC differentiating circuit where the voltage across the resistor behaves through time in the same manner as the voltage across an inductor. The op-amp follower buffers this voltage and applies it back to the input through the resistor RL. The desired effect is an impedance of the form of an ideal inductor L with a series resistance RL:

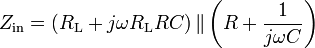

From the diagram, the input impedance of the op-amp circuit is:

With RLRC = L, it can be seen that the impedance of the simulated inductor is the desired impedance in parallel with the impedance of the RC circuit. In typical designs, R is chosen to be sufficiently large such that the first term dominates; thus, the RC circuit's impact on input impedance is negligible.

This is the same as a resistance RL in series with an inductance L = RLRC. There is a practical limit on the minimum value that RL can take, determined by the current output capability of the op amp.

Comparison with actual inductors

Simulated elements only imitate actual elements as in fact they are dynamic voltage sources. They cannot replace them in all the possible applications as they do not possess all their unique properties. So, the simulated inductor only mimics some properties of the real inductor.

Magnitudes. In typical applications, both the inductance and the resistance of the gyrator are much greater than that of a physical inductor. Gyrators can be used to create inductors from the microhenry range up to the megahenry range. Physical inductors are typically limited to tens of henries, and have parasitic series resistances from hundreds of microhms through the low kilohm range. The parasitic resistance of a gyrator depends on the topology, but with the topology shown, series resistances will typically range from tens of ohms through hundreds of kilohms.

Quality. Physical capacitors are often much closer to "ideal capacitors" than physical inductors are to "ideal inductors". Because of this, a synthesized inductor realized with a gyrator and a capacitor may, for certain applications, be closer to an "ideal inductor" than any (practical) physical inductor can be. Thus, use of capacitors and gyrators may improve the quality of filter networks that would otherwise be built using inductors. Also, the Q factor of a synthesized inductor can be selected with ease. The Q of an LC filter can be either lower or higher than that of an actual LC filter – for the same frequency, the inductance is much higher, the capacitance much lower, but the resistance also higher. Gyrator inductors typically have higher accuracy than physical inductors, due to the lower cost of precision capacitors than inductors.

Energy storage. Simulated inductors do not have the inherent energy storing properties of the real inductors and this limits the possible power applications. The circuit cannot respond like a real inductor to sudden input changes (it does not produce a high-voltage back EMF); its voltage response is limited by the power supply. Since gyrators use active circuits, they only function as a gyrator within the power supply range of the active element. Hence gyrators are usually not very useful for situations requiring simulation of the 'flyback' property of inductors, where a large voltage spike is caused when current is interrupted. A gyrator's transient response is limited by the bandwidth of the active device in the circuit and by the power supply.

Externalities. Simulated inductors do not react to external magnetic fields and permeable materials the same way that real inductors do. They also don't create magnetic fields (and induce currents in external conductors) the same way that real inductors do. This limits their use in applications such as sensors, detectors and transducers.

Grounding. The fact that one side of the simulated inductor is grounded restricts the possible applications (real inductors are floating). This limitation may preclude its use in some low-pass and notch filters.[9] However the gyrator can be used in a floating configuration with another gyrator so long as the floating "grounds" are tied together. This allows for a floating gyrator, but the inductance simulated across the input terminals of the gyrator pair must be cut in half for each gyrator to ensure that the desired inductance is met (the impedance of inductors in series adds together). This is not typically done as it requires even more components than in a standard configuration and the resulting inductance is a result of two simulated inductors, each with half of the desired inductance.

Applications

The primary application for a gyrator is to reduce the size and cost of a system by removing the need for bulky, heavy and expensive inductors. For example, RLC bandpass filter characteristics can be realized with capacitors, resistors and operational amplifiers without using inductors. Thus graphic equalizers can be achieved with capacitors, resistors and operational amplifiers without using inductors because of the invention of the gyrator.

Gyrator circuits are extensively used in telephony devices that connect to a POTS system. This has allowed telephones to be much smaller, as the gyrator circuit carries the DC part of the line loop current, allowing the transformer carrying the AC voice signal to be much smaller due to the elimination of DC current through it.[10] Gyrators are used in most DAAs (data access arrangements).[11] Circuitry in telephone exchanges has also been affected with gyrators being used in line cards. Gyrators are also widely used in hi-fi for graphic equalizers, parametric equalizers, discrete bandstop and bandpass filters such as rumble filters), and FM pilot tone filters.

There are many applications where it is not possible to use a gyrator to replace an inductor:

- High voltage systems utilizing flyback (beyond working voltage of transistors/amplifiers)

- RF systems (RF inductors are usually small anyhow)

- Power conversion, where a coil is used as energy storage.

See also

- Negative impedance converter (which can be used to implement a negative inductor with a capacitor)

- Sallen–Key topology

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 B. D. H. Tellegen (April 1948). "The gyrator, a new electric network element". Philips Res. Rep. 3: 81–101. Retrieved 2010-03-20.

- ↑ K. M. Adams, E. F. A. Deprettere and J. O. Voorman (1975). "The gyrator in electronic systems". In Ladislaus Marton. Advances in Electronics and Electron Physics (Academic Press, Inc.) 37: 79–180.

- ↑ Chua, Leon, EECS-100 Op Amp Gyrator Circuit Synthesis and Applications, Univ. of Calif. at Berkeley, retrieved May 3, 2010

- ↑ Fox, A. G.; Miller, S. E.; Weiss, M. T.. (January 1955). "Behavior and Applications of Ferrites in the Microwave Region". The Bell System Technical Journal 34 (1): 5–103.

- ↑ Graphic Symbols for Electrical and Electronics Diagrams (Including Reference Designation Letters): IEEE-315-1975 (Reaffirmed 1993), ANSI Y32.2-1975 (Reaffirmed 1989), CSA Z99-1975. IEEE and ANSI, New York, NY. 1993.

- ↑ Hogan, C. Lester (January 1952). "The Ferromagnetic Faraday Effect at Microwave Frequencies and its Applications - The Microwave Gyrator". The Bell System Technical Journal 31 (1): 1–31.

- ↑ The IEEE Standard Dictionary of Electrical and Electronics terms (6th ed.). IEEE. 1996 [1941]. ISBN 1-55937-833-6.

- ↑ Theodore Deliyannis, Yichuang Sun, J. Kel Fidler, Continuous-time active filter design, pp.81-82, CRC Press, 1999 ISBN 0-8493-2573-0.

- ↑ Carter, Bruce (July 2001). "An audio circuit collection, Part 3". Analog Applications Journal (Texas Instruments). SLYT134.. Carter page 1 states, "The fact that one side of the inductor is grounded precludes its use in low-pass and notch filters, leaving high-pass and band-pass filters as the only possible applications."

- ↑ Joe Randolph. AN-5: "Transformer-based phone line interfaces (DAA, FXO)".

- ↑ "Gyrator - DC Holding Circuit"

- Berndt, D. F.; Dutta Roy, S. C. (1969), "Inductor simulation with a single unity gain amplifier", IEEE Journal of Solid State Circuits SC–4: 161–162

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gyrators. |

- Good description of this form of the simulated inductor — Elliot Sound Products

- Another description, with the same circuit

- LC filter design using equal value R gyrator, an alternative design

- An alternative circuit

- Webarchive backup: Another alternative circuit

- Discussion of the gyrator in general and a macro for Micro-Cap V

- Java simulation of this circuit

- Single transistor gyrator for telephony applications

- SPICE Analysis of gyrator for telephony applications

- Negative floating inductor with only 2 Op-amps Article here