Guru Angad

| Guru Angad | |

|---|---|

Guru Nanak with Bhai Bala and Bhai Mardana and Sikh Gurus | |

| Born |

Bhai Lehna March 31, 1504 Matte Di Sarai, Muktsar, Punjab, India |

| Died |

March 28, 1552 (aged 47) Khadur Sahib, India |

| Other names | The Second Master |

| Years active | 1539–1552 |

| Known for | Popularizing the Gurmukhi Script |

| Predecessor | Guru Nanak |

| Successor | Guru Amar Das |

| Spouse(s) | Mata Khivi |

| Children | Baba Dasu, Baba Dattu, Bibi Amro, and Bibi Anokhi |

| Parents | Mata Sabharee (Daya Kaur) and Baba Pheru Mal |

Guru Angad (Punjabi: ਗੁਰੂ ਅੰਗਦ; 31 March 1504 – 28 March 1552) was the second of the ten Sikh Gurus. He was born in the village of Sarae Naga in Muktsar District in Punjab on 31 March 1504. The name Lehna was given shortly after his birth as was the custom of his Hindu parents. He was the son of a small but successful trader named Pheru Mal. His mother's name was Mata Ramo (also known as Mata Sabhirai, Mansa Devi and Daya Kaur). Baba Narayan Das Trehan was the Guru's Grandfather, whose ancestral house was at Matte-di-Sarai near Mukatsar.

In 1538, Guru Nanak chose Lehna—his disciple—to be his successor as Sikhism's Guru, rather than one of his sons.[1] Lehna was then given the name Angad and designated as Guru Angad, becoming the second guru of the Sikhs. He continued on the work started by the first Sikh Guru.

Guru Angad married Mata Khivi in January 1520 and had two sons (Dasu and Datu) and two daughters (Amro and Anokhi). The entire family of his father had left their ancestral village in fear of the invasion of Babar's armies. After this the family settled at Khadur Sahib, a village by the River Beas near what is now Tarn Taran a small town about 25 km from the city of Amritsar, the holiest of Sikh cities.

Devotion and service to Guru Nanak

One day, Bhai Lehna heard the recitation of a hymn of Guru Nanak from Bhai Jodha a neighbour who was a follower of the Guru. His mind was captured by the tune and while on his annual pilgrimage to Jawalamukhi Temple he asked his group if they would mind going to see the Guru. Everyone thought this most inappropriate and refused. Not one to shirk his responsibilities, he was after all the guide and leader of the group, he couldn't abandon them with thieves along the way. But man of honor and dharma that he was, the poems and prayers (kirtan) of Guru Nanak still held onto his every thought. So one night without telling anyone he mounted his horse and proceeded to the village now known as Kartarpur (God's city) to visit with Guru Nanak. Upon receiving directions to the Guru, Bhai Lehna found a number of people working on a field. Bhai Lehna did not recognize the Guru as he looked just like the ordinary field workers, and asked Guru Nanak if he could take him to the Guru. Nanak agreed and took the saddle strings of the horse while Bhai Lehna sat upon the horse comfortably. After some time the Guru reached his home and told Bhai Lehna to sit down whilst he went to get the Guru; when the Guru returned, this time after freshening up, Bhai Lehna realized instantly what a huge mistake he had made. He had several thoughts going through his head about what a huge sin he had committed by making the Guru pull him and his horse home whilst he sat upon the horse comfortably. His face at once dropped and Guru smiled, he asked what is your name, Bhai replied 'Bhai Lehna'. The Guru then replied: 'don't worry when someone comes to take something they would come as you have' (as Lehna means to take something) 'if you give me the strings of your mind as you did with the horse saddles and let me direct you, you will be amazed... '

Bhai Lehna displayed deep and loyal service to Guru Nanak. Several stories display how Bhai Lehna was chosen over the Guru's sons as his successor. One of these stories is about a jug which fell into mud. Guru Nanak's sons would not pick it up; Sri Chand, the older, refused on the grounds that the filth would pollute him, and Lakshmi Chand, the younger, objected because the task was too menial for the son of a Guru. Bhai Lehna, however, picked it out of the mud, washed it clean, and presented it to Guru Nanak full of water.[2] A different version of this story counts this as a key part of Guru Nanak deciding upon Bhai Lehna for his successor. The Guru's wife, Mata, said to Nanak "My Lord, keep my sons in mind," meaning that she wished them to be the ones considered for succession to the guruship. Guru ordered them to come, and he threw a bowl into a tank of muddy water. The Guru ordered them to retrieve it for him, and both of them refused to do it. Guru Nanak then asked Bhai Lehna to retrieve it, and Bhai Lehna promptly complied.[3] In one instance, the Guru orders a wall of his house, which had fallen down, to be repaired. His sons refused to fix it immediately because of the storm that had knocked it down, and the lateness of morning. Guru Nanak said that he needed no masons while he had his Sikhs, and ordered them to repair it. Bhai Lehna started to repair the wall, but Nanak claimed that it was crooked when he was finished, and ordered him to knock it down and build it again. Bhai Lehna complied, and Nanak still claimed the wall was not straight. The Guru ordered him to attempt it a third time. At this, the Guru's sons called Bhai Lehna a fool for putting up with such unreasonable orders. Bhai Lehna simply replied that a servant's hands should be busy doing his master's work.[4] Yet another anecdote exists where Guru Nanak asks his Sikhs and his sons to carry three bundles of grass for his cows and buffaloes, and, as with the other examples, his sons and his followers failed to show loyalty. Bhai Lehna, however, immediately asked to be tasked with carrying the bundles, which were wet and muddy. When Bhai Lehna and the Guru arrived at the Guru's house, the Guru's wife complained at Guru Nanak's terrible treatment of a guest, noting how his clothes were covered from head to foot with mud. Guru Nanak then replied to her, "This is not mud; it is the saffron of God's court, which marketh the elect." Upon another inspection, the Guru's wife saw that Bhai Lehna's clothes had, indeed, changed into saffron. To this day, Sikhs consider the three bundles as important symbols of spiritual affairs, temporal affairs, and the Guruship.[5] In one of the most significant stories, Guru Nanak travels through the forest with his disciples. The Guru made gold and silver coins appear in front of the group, and all but two followers ran to pick them up: Bhai Lehna and Bhai Buddha. Guru Nanak led them both to a funeral pyre, and ordered them to eat the corpse that was hidden under a shroud. Bhai Buddha started thinking, but Bhai Lehna obeyed. When he lifted the shroud, he found the Guru Nanak himself underneath it.[2] In a different version of this story, Bhai Lehna is met with Parshad (sacred food) instead of Guru Nanak. Bhai Lehna offers the Parshad to the Guru, satisfied to eat of the leavings. Guru Nanak, after this test, reveals the Japuji to Bhai Lehna, proclaims Bhai Lehna is of his own image, and promises that Bhai Lehna shall be the next Guru.[6]

Guru Nanak had touched him and renamed him Angad (part of the body) or the second Nanak on 7 September 1539. Before becoming the new Guru he had spent six or seven years in the service of Guru Nanak at Kartarpur.

After the death of Guru Nanak on 22 September 1539, Guru Angad left Kartarpur for the village of Khadur Sahib (near Goindwal Sahib). He carried forward the principles of Guru Nanak both in letter and spirit. Yogis and Saints of different sects visited him and held detailed discussions about Sikhi with him.

Guru Angad (1539–1552)

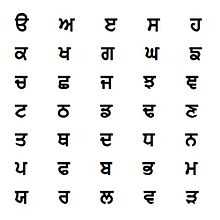

Guru Angad popularized the present form of the Gurmukhi script. It became the medium of writing the Punjabi language in which the hymns of the Gurus are expressed. This step had a far-reaching purpose and impact. First, it gave the people who spoke this language an identity of their own, enabling them to express their thought directly and without any difficulty or transliteration. The measure had the effect of establishing the independence of the mission and the followers of the Guru. Secondly, it helped the community to dissociate itself from the Sanskrit religious tradition so that the growth and development of the Sikhs could take place unhampered and unprejudiced by the backlog of the earlier religious and social philosophies and practices. This measure, as shown by the subsequent growth of Sikhism, was essential in order to secure its unhindered development and progress as it required an entirely different approach to life.

Dr Gupta feels that this step, to a certain extent, kept the upper classes among Hindus, to which the Guru belonged, away from Sikhism, partly because they were steeped in the old religious and Brahmin tradition and partly because the Sanskrit tradition fed their ego by giving them a superior caste status to that of the other castes. But, the idea of equality of man was fundamental to the Sikh spiritual system. The Guru knew that its association with traditional religious literature would tend to water it down. The matter is extremely important from the point of view of the historical growth and study. Actually, the students of Sikh history know that over the centuries the influence of these old traditions has been very much in evidence. It has sometimes even given a wrong twist to the new thesis and its growth. The educated persons were almost entirely drawn from the upper castes and classes. They had a vested interest, visible also in their writings, in introducing ideas and practices which helped in maintaining their privileges and prejudices of caste superiority, even though such customs were opposed to the fundamentals about the equality of man laid down by the Gurus. For example, the Jats, who were themselves drawn from classes branded as low by the Brahmin system, started exhibiting caste prejudices vis-a-vis the lower castes drawn from the Hindu fold.

Earlier, the Punjabi language was written in the Landa or Mahajani script. This had no vowel sounds, which had to be imagined or construed by the reader in order to decipher the writing. Therefore, there was the need of a script which could faithfully reproduce the hymns of the Gurus so that the true meaning and message of the Gurus could not be misconstrued and misinterpreted by each reader to suit his own purpose and prejudices. The devising of the Gurmukhi script was an essential step in order to maintain the purity of the doctrine and exclude all possibility of misunderstanding and misconstruction by interested persons.

The institution of the langar was maintained and developed. The Guru's wife personally worked in the kitchen. She also served food to the members of the community and the visitors. Her devotion to this institution finds mention in the Guru Granth Sahib.

The Guru earned his own living by twisting coarse grass into strings used for cots. All offerings went to the common fund. This demonstrates that it is necessary and honorable to do even the meanest productive work. It also emphasizes that parasitical living is not in consonance with the mystic and moral path. In line with Guru Nanak's teaching, the Guru also declared that there was no place for passive recluses in the community.

Like Guru Nanak, Guru Angad and the subsequent Gurus selected and appointed their successors by completely satisfying themselves about their mystic fitness and capacity to discharge the responsibilities of the mission.

Community work

Guru Angad is credited with introducing a new alphabet known as Gurmukhi script that he made in Khadur Sahib, modifying the old Punjabi script's characters. There is evidence, however, that this was not the case: one hymn written in acrostic form by Guru Nanak gives proof that the alphabet already existed.[7] Soon, this script became very popular and started to be used by the people in general. He took great interest in the education of children by opening many schools for their instruction and thus increased the number of literate people. For the youth he started the tradition of Mall Akhara, where physical as well as spiritual exercises were held. He collected the facts about Guru Nanak's life from Bhai Bala and wrote the first biography of Guru Nanak. He also wrote 63 Saloks (stanzas), which are included in the Guru Granth Sahib. He popularised and expanded the institution of Guru ka Langar (the Guru's communal kitchen) that had been started by Guru Nanak.

Guru Angad travelled widely and visited all important religious places and centres established by Guru Nanak for the preaching of Sikhi. He also established hundreds of new centres of Sikhi and thus strengthened its base. The period of his Guruship was the most crucial one. The Sikh community had moved from having a founder to a succession of Gurus and the infrastructure of Sikh society was strengthened and crystallised – from being an infant, Sikhi had moved to being a young child, ready to face the dangers that were around. During this phase, Sikhi established its own separate religious identity.

Death and successor

Guru Angad, following the example set by Guru Nanak, nominated Guru Amar Das as his successor (The Third Nanak) before his death. He presented all the holy scripts, including those he received from Guru Nanak, to Guru Amar Das. He died on 29 March 1552 at the age of forty-eight. It is said that he started to build a new town, at Goindwal near Khadur Sahib and Guru Amar Das was appointed to supervise its construction. It is also said that the deposed Mughal Emperor Humayun (Babar's son), while being pursued by Sher Shah Suri, came to obtain the blessings of Guru Angad in regaining the throne of Delhi.

See also

- List of places named after Guru Angad Dev

- Samrat Hem Chandra Vikramaditya

References

- ↑ Shackle, Christopher; Mandair, Arvind-Pal Singh (2005). Teachings of the Sikh Gurus: Selections from the Sikh Scriptures. United Kingdom: Routledge. xiii–xiv. ISBN 0-415-26604-1.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Cole, W. Owen; Sambhi, Piara Singh (1978). The Sikhs: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. 18. ISBN 0-7100-8842-6.

- ↑ Sikh Missionary Center (1990). Sikh Religion. Detroit: Sikh Missionary Center. 68. ISBN 0-9625383-0-2.

- ↑ Sikh Missionary Center (1990). Sikh Religion. Detroit: Sikh Missionary Center. 69. ISBN 0-9625383-0-2.

- ↑ Sikh Missionary Center (1990). Sikh Religion. Detroit: Sikh Missionary Center. 68–69. ISBN 0-9625383-0-2.

- ↑ Sikh Missionary Center (1990). Sikh Religion. Detroit: Sikh Missionary Center. 69–70. ISBN 0-9625383-0-2.

- ↑ Cole, W. Owen; Sambhi, Piara Singh (1978). The Sikhs: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. 19. ISBN 0-7100-8842-6.

8.Harjinder Singh Dilgeer, SIKH HISTORY (in English) in 10 volumes, especially volume 1 (published by Singh Brothers Amritsar, 2009–2011).

- Sikh Gurus, Their Lives and Teachings, K.S. Duggal

External links

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Guru Angad |

- DiscoverSikhism - Sri Guru Angad Dev Ji Sri Guru Angad Dev Ji is second of the Ten Sikh Gurus. Read about his life and stories here.

- sikhs.org

- sikh-history.com

- sikhmissionarysociety.org

- Guru Angad Ji Biography

- allaboutsikhs.com

- Learn more about Sri Guru Angad Ji

- Guru Angad Sahib Ji

Audio:

| Preceded by: Guru Nanak (20 October 1469 – 7 May 1539) |

Guru Angad | Followed by: Guru Amar Das (5 April 1479 – 1 September 1574) |

| |||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|