Grothendieck–Riemann–Roch theorem

In mathematics, specifically in algebraic geometry, the Grothendieck–Riemann–Roch theorem is a far-reaching result on coherent cohomology. It is a generalisation of the Hirzebruch–Riemann–Roch theorem, about complex manifolds, which is itself a generalisation of the classical Riemann–Roch theorem for line bundles on compact Riemann surfaces.

Riemann–Roch type theorems relate Euler characteristics of the cohomology of a vector bundle with their topological degrees, or more generally their characteristic classes in (co)homology or algebraic analogues thereof. The classical Riemann–Roch theorem does this for curves and line bundles, whereas the Hirzebruch–Riemann–Roch theorem generalises this to vector bundles over manifolds. The Grothendieck–Riemann–Roch theorem sets both theorems in a relative situation of a morphism between two manifolds (or more general schemes) and changes the theorem from a statement about a single bundle, to one applying to chain complexes of sheaves.

The theorem has been very influential, not least for the development of the Atiyah–Singer index theorem. Conversely, complex analytic analogues of the Grothendieck–Riemann–Roch theorem can be proved using the index theorem for families. Alexander Grothendieck gave a first proof in a 1957 manuscript, later published.[1] Armand Borel and Jean-Pierre Serre wrote up and published Grothendieck's proof in 1958.[2] Later, Grothendieck and his collaborators simplified and generalized the proof.[3]

Formulation

Let X be a smooth quasi-projective scheme over a field. Under these assumptions, the Grothendieck group

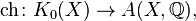

of bounded complexes of coherent sheaves is canonically isomorphic to the Grothendieck group of bounded complexes of finite-rank vector bundles. Using this isomorphism, consider the Chern character (a rational combination of Chern classes) as a functorial transformation

where

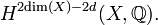

is the Chow group of cycles on X of dimension d modulo rational equivalence, tensored with the rational numbers. In case X is defined over the complex numbers, the latter group maps to the topological cohomology group

Now consider a proper morphism

between smooth quasi-projective schemes and a bounded complex of sheaves

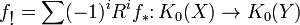

The Grothendieck–Riemann–Roch theorem relates the pushforward map

and the pushforward

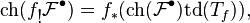

by the formula

Here td(X) is the Todd genus of (the tangent bundle of) X. Thus the theorem gives a precise measure for the lack of commutativity of taking the push forwards in the above senses and the Chern character and shows that the needed correction factors depend on X and Y only. In fact, since the Todd genus is functorial and multiplicative in exact sequences, we can rewrite the Grothendieck–Riemann–Roch formula as

where Tf is the relative tangent sheaf of f, defined as the element TX − f*TY in K0(X). For example, when f is a smooth morphism, Tf is simply a vector bundle, known as the tangent bundle along the fibers of f.

Generalising and specialising

Generalisations of the theorem can be made to the non-smooth case by considering an appropriate generalisation of the combination ch(—)td(X) and to the non-proper case by considering cohomology with compact support.

The arithmetic Riemann–Roch theorem extends the Grothendieck–Riemann–Roch theorem to arithmetic schemes.

The Hirzebruch–Riemann–Roch theorem is (essentially) the special case where Y is a point and the field is the field of complex numbers.

History

Alexander Grothendieck's version of the Riemann–Roch theorem was originally conveyed in a letter to Jean-Pierre Serre around 1956–7. It was made public at the initial Bonn Arbeitstagung, in 1957. Serre and Armand Borel subsequently organized a seminar at Princeton to understand it. The final published paper was in effect the Borel–Serre exposition.

The significance of Grothendieck's approach rests on several points. First, Grothendieck changed the statement itself: the theorem was, at the time, understood to be a theorem about a variety, whereas Grothendieck saw it as a theorem about a morphism between varieties. By finding the right generalization, the proof became simpler while the conclusion became more general. In short, Grothendieck applied a strong categorical approach to a hard piece of analysis. Moreover, Grothendieck introduced K-groups, as discussed above, which paved the way for algebraic K-theory.

Notes

References

- Borel, Armand; Serre, Jean-Pierre (1958), "Le théorème de Riemann–Roch", Bulletin de la Société Mathématique de France (in French) 86: 97–136, ISSN 0037-9484, MR 0116022

- Fulton, William (1998), Intersection theory, Ergebnisse der Mathematik und ihrer Grenzgebiete. 3. Folge. 2 (2nd ed.), Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 3-540-62046-X, MR 1644323, Zbl 0885.14002

- Berthelot, Pierre; Alexandre Grothendieck, Luc Illusie, eds. (1971). Séminaire de Géométrie Algébrique du Bois Marie - 1966-67 - Théorie des intersections et théorème de Riemann-Roch - (SGA 6) (Lecture notes in mathematics 225) (in French). Berlin; New York: Springer-Verlag. xii+700. doi:10.1007/BFb0066283. ISBN 978-3-540-05647-8.

External links

- The thread "how does one understand GRR? (Grothendieck Riemann Roch)" on MathOverflow.