Great Wall of China

| Great Wall of China 万里长城 | |

|---|---|

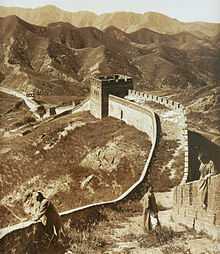

The Great Wall of China at Jinshanling | |

Map of all the wall constructions | |

| General information | |

| Type | Fortification |

| Country |

|

| Coordinates | 40°40′37″N 117°13′55″E / 40.67693°N 117.23193°ECoordinates: 40°40′37″N 117°13′55″E / 40.67693°N 117.23193°E |

| Construction started | 7th century BC |

| Technical details | |

| Size | 21,196 km (13,171 mi)[1] |

| Official name: The Great Wall | |

| Type: | Cultural |

| Criteria: | i, ii, iii, iv, vi |

| Designated: | 1987 (11th session) |

| Reference No. | 438 |

| State Party: | China |

| Region: | Asia-Pacific |

| Great Wall of China | |||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 长城 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 長城 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | long fortress | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 万里长城 | ||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 萬里長城 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | The long wall of 10,000 Li (里)[2] | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The Great Wall of China is a series of fortifications made of stone, brick, tamped earth, wood, and other materials, generally built along an east-to-west line across the historical northern borders of China in part to protect the Chinese Empire or its prototypical states against intrusions by various nomadic groups or military incursions by various warlike peoples or forces. Several walls were being built as early as the 7th century BC;[3] these, later joined together and made bigger and stronger, are now collectively referred to as the Great Wall.[4] Especially famous is the wall built between 220–206 BC by the first Emperor of China, Qin Shi Huang. Little of that wall remains. Since then, the Great Wall has on and off been rebuilt, maintained, and enhanced; the majority of the existing wall was reconstructed during the Ming Dynasty.

Other purposes of the Great Wall have included border controls, allowing the imposition of duties on goods transported along the Silk Road, regulation or encouragement of trade and the control of immigration and emigration. Furthermore, the defensive characteristics of the Great Wall were enhanced by the construction of watch towers, troop barracks, garrison stations, signaling capabilities through the means of smoke or fire, and the fact that the path of the Great Wall also served as a transportation corridor.

The Great Wall stretches from Shanhaiguan in the east, to Lop Lake in the west, along an arc that roughly delineates the southern edge of Inner Mongolia. A comprehensive archaeological survey, using advanced technologies, has concluded that the Ming walls measure 8,850 km (5,500 mi).[5] This is made up of 6,259 km (3,889 mi) sections of actual wall, 359 km (223 mi) of trenches and 2,232 km (1,387 mi) of natural defensive barriers such as hills and rivers.[5] Another archaeological survey found that the entire wall with all of its branches measure out to be 21,196 km (13,171 mi).[6]

History

Early walls

The Chinese were already familiar with the techniques of wall-building by the time of the Spring and Autumn period between the 8th and 5th centuries BC.[7] During this time and the subsequent Warring States period, the states of Qin, Wei, Zhao, Qi, Yan and Zhongshan[8][9] all constructed extensive fortifications to defend their own borders. Built to withstand the attack of small arms such as swords and spears, these walls were made mostly by stamping earth and gravel between board frames.

Qin Shi Huang conquered all opposing states and unified China in 221 BC, establishing the Qin Dynasty. Intending to impose centralized rule and prevent the resurgence of feudal lords, he ordered the destruction of the wall sections that divided his empire along the former state borders. To protect the empire against intrusions by the Xiongnu people from the north, he ordered the building of a new wall to connect the remaining fortifications along the empire's new northern frontier. Transporting the large quantity of materials required for construction was difficult, so builders always tried to use local resources. Stones from the mountains were used over mountain ranges, while rammed earth was used for construction in the plains. There are no surviving historical records indicating the exact length and course of the Qin Dynasty walls. Most of the ancient walls have eroded away over the centuries, and very few sections remain today. The human cost of the construction is unknown, but it has been estimated by some authors that hundreds of thousands,[10] if not up to a million, workers died building the Qin wall.[11][12] Later, the Han,[13] Sui, and Northern dynasties all repaired, rebuilt, or expanded sections of the Great Wall at great cost to defend themselves against northern invaders.[14] The Tang and Song Dynasties did not build any walls in the region.[14] The Liao, Jin, and Yuan dynasties, who ruled Northern China throughout most of the 10th–13th centuries, had their original power bases north of the Great Wall proper. Accordingly, they would have no need throughout most of their history to build a wall along this line. The Liao carried out limited repair of the Great Wall in a few areas,[15] however the Jin did construct defensive walls in the 12th century, but those were located much to the north of the Great Wall as we know it, within today's Inner and Outer Mongolia.[14][16]

Ming era

The Great Wall concept was revived again during the Ming Dynasty in the 14th century,[17] and following the Ming army's defeat by the Oirats in the Battle of Tumu. The Ming had failed to gain a clear upper hand over the Manchurian and Mongolian tribes after successive battles, and the long-drawn conflict was taking a toll on the empire. The Ming adopted a new strategy to keep the nomadic tribes out by constructing walls along the northern border of China. Acknowledging the Mongol control established in the Ordos Desert, the wall followed the desert's southern edge instead of incorporating the bend of the Huang He.

Unlike the earlier Qin fortifications, the Ming construction was stronger and more elaborate due to the use of bricks and stone instead of rammed earth. Up to 25,000 watchtowers are estimated to have been constructed on the wall.[18] As Mongol raids continued periodically over the years, the Ming devoted considerable resources to repair and reinforce the walls. Sections near the Ming capital of Beijing were especially strong.[19] Qi Jiguang between 1567 and 1570 also repaired and reinforced the wall, faced sections of the ram-earth wall with bricks and constructed 1,200 watchtowers from Shanhaiguan Pass to Changping to warn of approaching Mongol raiders.[20] During the 1440s–1460s, the Ming also built a so-called "Liaodong Wall". Similar in function to the Great Wall (whose extension, in a sense, it was), but more basic in construction, the Liaodong Wall enclosed the agricultural heartland of the Liaodong province, protecting it against potential incursions by Jurched-Mongol Oriyanghan from the northwest and the Jianzhou Jurchens from the north. While stones and tiles were used in some parts of the Liaodong Wall, most of it was in fact simply an earth dike with moats on both sides.[21]

Towards the end of the Ming Dynasty, the Great Wall helped defend the empire against the Manchu invasions that began around 1600. Even after the loss of all of Liaodong, the Ming army under the command of Yuan Chonghuan held off the Manchus at the heavily fortified Shanhaiguan pass, preventing the Manchus from entering the Chinese heartland. The Manchus were finally able to cross the Great Wall in 1644, after Beijing had fallen to Li Zicheng's rebels. The gates at Shanhaiguan were opened by the commanding Ming general Wu Sangui on May 25 who formed an alliance with the Manchus, hoping to use the Manchus to expel the rebels from Beijing.[22] On 26 May 1644, Wu ordered his soldiers to wear a white cloth attached to their armor, to distinguish them from Li Zicheng's forces.[23] The Manchus quickly seized Beijing, and defeated both the rebel-founded Shun Dynasty and the remaining Ming resistance, establishing the Qing Dynasty rule over all of China.[23]

In 2009, an additional 290 km (180 mi) of previously undetected portions of the wall, built during the Ming Dynasty, were discovered. The newly discovered sections range from the Hushan mountains in the northern Liaoning province, to Jiayuguan in western Gansu province. The sections had been submerged over time by sandstorms which moved across the arid region.[24]

Under Qing rule, China's borders extended beyond the walls and Mongolia was annexed into the empire, so construction and repairs on the Great Wall were discontinued. On the other hand, the so-called Willow Palisade, following a line similar to that of the Ming Liaodong Wall, was constructed by the Qing rulers in Manchuria. Its purpose, however, was not defense but rather migration control.

Early Western reports of the wall

The North African traveler Ibn Battuta, who was in Guangzhou ca. 1346, inquired among the local Muslims about the wall that, according to the Qur'an, Dhul-Qarnayn had built to contain Gog and Magog. Ibn Battuta reported that the wall was "sixty days' travel" from the city of Zeitun (Quanzhou);[25] Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen Gibb noted Ibn Battuta has confused the Great Wall of China with that built by Dhul-Qarnayn.[25] This indicated that Arabs may have heard about China's Great Wall during earlier periods of China's history, and associated it with the Gog and Magog wall of the Qur'an.[16] But, in any event, no one of Ibn Battuta's Guangzhou interlocutors had seen the wall or knew anyone who had seen it, which implies that by the late Yuan the existence of the Great Wall was not in the people's living memory, at least not in the Muslim communities in Guangzhou.[16]

Soon after Europeans reached the Ming China in the early 16th century, accounts of the Great Wall started to circulate in Europe, even though no European was to see it with his own eyes for another century. Possibly one of the earliest descriptions of the wall, and its significance for the defense of the country against the "Tartars" (i.e. Mongols), may be the one contained in the Third Década of João de Barros' Asia (published 1563).[26] Interestingly, Barros himself did not travel to Asia, but was able to use Chinese books brought to Lisbon by Portuguese traders.[27] Other early accounts in Western sources include those of Gaspar da Cruz, Bento de Goes, Matteo Ricci, and Bishop Juan González de Mendoza.[28] In 1559, in his work "A Treatise of China and the Adjoyning Regions," Gaspar da Cruz offers an early discussion of the Great Wall in which he notes, “a Wall of an hundred leagues in length. And some will affirme to bee more than a hundred leagues.”[28] Another early account written by Bishop Juan González de Mendoza (translated into English in 1588) reported a wall five hundred leagues long, but suggested that only one hundred leagues were manmade with the rest natural rock formations.[28] In another early Western account, Louis J. Gallagher’s translations (published in 1953) of the journals of the famous Jesuit Matteo Ricci (1552–1610) show that Ricci mentioned the Great Wall once in his diary, noting the existence of “a tremendous wall four hundred and five miles long” that formed part of the northern defenses of the Ming Empire.[28] In yet another case, Ivan Petlin’s 1619 deposition for his Russian embassy mission offers an early account based on a firsthand encounter with the Great Wall, and mentions that in the course of his journey his embassy travelled alongside the Great Wall for ten days.[28] One of the earliest records of a Western traveler entering China via a Great Wall pass (Jiayuguan, in this case) may be that of the Portuguese Jesuit brother Bento de Góis, who had reached China's north-western gate from India in 1605.[29]

Notable areas

Some of the following sections are in Beijing municipality, which were renovated and which are regularly visited by tourists today.

- "North Pass" of Juyongguan pass, known as the Badaling. When used by the Chinese to protect their land, this section of the wall had many guards to defend China’s capital Beijing. Made of stone and bricks from the hills, this portion of the Great Wall is 7.8 meters (26 ft) high and 5 meters (16 ft) wide.

- "West Pass" of Jiayuguan (pass). This fort is near the western edges of the Great Wall.

- "Pass" of Shanhaiguan. This fort is near the eastern edges of the Great Wall.

- One of the most striking sections of the Ming Great Wall is where it climbs extremely steep slopes. It runs 11 kilometers (6.8 mi) long, ranges from 5 to 8 meters (16–26 ft) in height, and 6 meters (20 ft) across the bottom, narrowing up to 5 meters (16 ft) across the top. Wangjinglou is one of Jinshanling's 67 watchtowers, 980 meters (3,220 ft) above sea level.

- South East of Jinshanling, is the Mutianyu Great Wall which winds along lofty, cragged mountains from the southeast to the northwest for approximately 2.25 kilometers (about 1.3 miles). It is connected with Juyongguan Pass to the west and Gubeikou to the east. This section was one of the first to be renovated following the turmoil of the Cultural Revolution.[30]

- 25 km (16 mi) west of the Liao Tian Ling stands a part of the Great Wall which is only 2–3 stories high. According to the records of Lin Tian, the wall was not only extremely short compared to others, but it appears to be silver. Archeologists explain that the wall appears to be silver because the stone they used were from Shan Xi, where many mines are found. The stone contains extremely high levels of metal in it causing it to appear silver. However, due to years of decay of the Great Wall, it is hard to see the silver part of the wall today.

- Another notable section lies near the eastern extremity of the wall, where the first pass of the Great Wall was built on the Shanhaiguan (known as the “Number One Pass Under Heaven”). 3 km north of Shanhaiguan is Jiaoshan Great Wall, the site of the first mountain of the Great Wall.[31] 15 km northeast from Shanhaiguan, is the Jiumenkou, which is the only portion of the wall that was built as a bridge.

Characteristics

Before the use of bricks, the Great Wall was mainly built from rammed earth, stones, and wood. During the Ming Dynasty, however, bricks were heavily used in many areas of the wall, as were materials such as tiles, lime, and stone. The size and weight of the bricks made them easier to work with than earth and stone, so construction quickened. Additionally, bricks could bear more weight and endure better than rammed earth. Stone can hold under its own weight better than brick, but is more difficult to use. Consequently, stones cut in rectangular shapes were used for the foundation, inner and outer brims, and gateways of the wall. Battlements line the uppermost portion of the vast majority of the wall, with defensive gaps a little over 30 cm (12 in) tall, and about 23 cm (9.1 in) wide. From the parapets, guards could survey the surrounding land.[32] Communication between the army units along the length of the Great Wall, including the ability to call reinforcements and warn garrisons of enemy movements, was of high importance. Signal towers were built upon hill tops or other high points along the wall for their visibility. Wooden gates could be used as a trap against those going through. Barracks, stables, and armories were built near the wall's inner surface.[32]

Condition

While some portions north of Beijing and near tourist centers have been preserved and even extensively renovated, in many locations the Wall is in disrepair. Those parts might serve as a village playground or a source of stones to rebuild houses and roads.[33] Sections of the Wall are also prone to graffiti and vandalism. Parts have been destroyed because the Wall is in the way of construction.[34]

More than 60 km (37 mi) of the wall in Gansu province may disappear in the next 20 years, due to erosion from sandstorms. In places, the height of the wall has been reduced from more than 5 metres (16 feet) to less than 2 metres (6.6 ft). The square lookout towers that characterize the most famous images of the wall have disappeared completely. Many western sections of the wall are constructed from mud, rather than brick and stone, and thus are more susceptible to erosion.[35] In August 2012, a 30-meter (98 ft) section of the wall in north China's Hebei province collapsed after days of continuous heavy rains.[36]

Visibility from space

Visibility from the Moon

One of the earliest known references to this myth appears in a letter written in 1754 by the English antiquary William Stukeley. Stukeley wrote that, "This mighty wall of four score miles in length (Hadrian's Wall) is only exceeded by the Chinese Wall, which makes a considerable figure upon the terrestrial globe, and may be discerned at the Moon."[37] The claim was also mentioned by Henry Norman in 1895 where he states "besides its age it enjoys the reputation of being the only work of human hands on the globe visible from the Moon."[38] The issue of "canals" on Mars was prominent in the late 19th century and may have led to the belief that long, thin objects were visible from space.[39] The claim that the Great Wall is visible also appears in 1932's Ripley's Believe It or Not! strip[40] and in Richard Halliburton's 1938 book Second Book of Marvels.

The claim the Great Wall is visible has been debunked many times,[41] but is still ingrained in popular culture.[42] The wall is a maximum 9.1 m (30 ft) wide, and is about the same color as the soil surrounding it. Based on the optics of resolving power (distance versus the width of the iris: a few millimeters for the human eye, meters for large telescopes) only an object of reasonable contrast to its surroundings which is 70 mi (110 km) or more in diameter (1 arc-minute) would be visible to the unaided eye from the Moon, whose average distance from Earth is 384,393 km (238,851 mi). The apparent width of the Great Wall from the Moon is the same as that of a human hair viewed from 2 miles (3.2 km) away. To see the wall from the Moon would require spatial resolution 17,000 times better than normal (20/20) vision.[43] Unsurprisingly, no lunar astronaut has ever claimed to have seen the Great Wall from the Moon.

Visibility from low Earth orbit

A more controversial question is whether the Wall is visible from low Earth orbit (an altitude of as little as 100 miles (160 km)). NASA claims that it is barely visible, and only under nearly perfect conditions; it is no more conspicuous than many other man-made objects.[44] Other authors have argued that due to limitations of the optics of the eye and the spacing of photoreceptors on the retina, it is impossible to see the wall with the naked eye, even from low orbit, and would require visual acuity of 20/3 (7.7 times better than normal).[43]

Astronaut William Pogue thought he had seen it from Skylab but discovered he was actually looking at the Grand Canal of China near Beijing. He spotted the Great Wall with binoculars, but said that "it wasn't visible to the unaided eye." U.S. Senator Jake Garn claimed to be able to see the Great Wall with the naked eye from a space shuttle orbit in the early 1980s, but his claim has been disputed by several U.S. astronauts. Veteran U.S. astronaut Gene Cernan has stated: "At Earth orbit of 100 miles (160 km) to 200 miles (320 km) high, the Great Wall of China is, indeed, visible to the naked eye." Ed Lu, Expedition 7 Science Officer aboard the International Space Station, adds that, "it's less visible than a lot of other objects. And you have to know where to look."

In 2001, Neil Armstrong stated about the view from Apollo 11: "I do not believe that, at least with my eyes, there would be any man-made object that I could see. I have not yet found somebody who has told me they've seen the Wall of China from Earth orbit. ...I've asked various people, particularly Shuttle guys, that have been many orbits around China in the daytime, and the ones I've talked to didn't see it."[45]

In October 2003, Chinese astronaut Yang Liwei stated that he had not been able to see the Great Wall of China. In response, the European Space Agency (ESA) issued a press release reporting that from an orbit between 160 and 320 kilometres (99 and 199 mi), the Great Wall is visible to the naked eye. In an attempt to further clarify things, the ESA published a picture of a part of the “Great Wall” photographed from Space. However, in a press release a week later (no longer available in the ESA’s website), they acknowledged that the "Great Wall" in the picture was actually a river.[43]

Leroy Chiao, a Chinese-American astronaut, took a photograph from the International Space Station that shows the wall. It was so indistinct that the photographer was not certain he had actually captured it. Based on the photograph, the China Daily later reported that the Great Wall can be seen from space with the naked eye, under favorable viewing conditions, if one knows exactly where to look.[46] However, the resolution of a camera can be much higher than the human visual system, and the optics much better, rendering photographic evidence irrelevant to the issue of whether it is visible to the naked eye.[43]

Gallery

-

"The First Mound"--at Jiayuguan, the western terminus

-

Great Wall of China near Jinshanling

-

The Great Wall of China at Badaling

-

A portion of the Great Wall of China at Simatai, overlooking the gorge

-

Mutianyu Great Wall, China. This is atop the wall on a section that has not been restored.

-

The Old Dragon Head, the eastern end of the Great Wall where it meets the sea in the vicinity of Shanhaiguan

See also

References

- ↑ "China’s Great Wall Found To Measure More Than 20,000 Kilometers". Bloomberg. 2012-06-05. Retrieved 2012-06-06.

- ↑ 10,000 li = 6,508 km (4,044 mi). In Chinese, 10,000 figuratively means "infinite", and the number should not be interpreted for its actual value, but rather as meaning the "infinitely long wall".

- ↑ The New York Times with introduction by Sam Tanenhaus (2011). The New York Times Guide to Essential Knowledge: A Desk Reference for the Curious Mind. St. Martin's Press of Macmillan Publishers. p. 1131. ISBN 978-0-312-64302-7. "Beginning as separate sections of fortification around the 7th century B.C. and unified during the Qin Dynasty in the 3rd century B.C., this wall, built of earth and rubble with a facing of brick or stone, runs from east to west across China for over 4,000 miles."

- ↑ "Great Wall of China". Encyclopædia Britannica. "Large parts of the fortification system date from the 7th through the 4th century BC. In the 3rd century BC Shihuangdi (Qin Shihuang), the first emperor of a united China (under the Qin dynasty), connected a number of existing defensive walls into a single system. Traditionally, the eastern terminus of the wall was considered to be Shanhai Pass (Shanhaiguan) in eastern Hebei province along the coast of the Bo Hai (Gulf of Chihli), and the wall’s length—without its branches and other secondary sections—was thought to extend for some 4,160 miles (6,700 km)."

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Great Wall of China 'even longer'". BBC. April 20, 2009. Retrieved April 20, 2009.

- ↑ "Great Wall of China even longer than previously thought". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 2012-06-06. Retrieved 2012-06-06.

- ↑ "歷代王朝修長城". Chiculture.net. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- ↑ "古代长城——战争与和平的纽带". Newsmth.net. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- ↑ "万里长城". Newsmth.net. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- ↑ Slavicek, Louise Chipley; Mitchell, George J.; Matray, James I. (2005). The Great Wall of China. Infobase Publishing. p. 35. ISBN 0-7910-8019-6

- ↑ Evans, Thammy (2006). Great Wall of China: Beijing & Northern China. Bradt Travel Guide. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 3. ISBN 1-84162-158-7

- ↑ "Defense and Cost of The Great Wall – page 3". Paul and Bernice Noll's Window on the World. Retrieved July 26, 2011.

- ↑ Coonan, Clifford (2012-02-27). "British researcher discovers piece of Great Wall 'marooned outside China'". The Irish Times. Retrieved 2012-02-28.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Waldron, Arthur N. (1983). "The Problem of The Great Wall of China". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 43 (2): 643–663. doi:10.2307/2719110. JSTOR 2719110

- ↑ Kenneth Pletcher from the Britannica Educational Publishing (2010). The Geography of China: Sacred and Historic Places. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 95. ISBN 1-61530-182-8.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Haw, Stephen G. (2006). Marco Polo's China: a Venetian in the realm of Khubilai Khan. Volume 3 of Routledge studies in the early history of Asia. Psychology Press. pp. 52–54. ISBN 0-415-34850-1

- ↑ Mooney, Paul and Catherine Karnow (2008). National Geographic Traveler: Beijing. National Geographic Books. p. 192. ISBN 1-4262-0231-8.

- ↑ Szabó, Jozsef, Lorant David and Denes Loczy (2010). Anthropogenic Geomorphology: A Guide to Man-made Landforms. Springer. p. 220. ISBN 978-9-048-13057-3.

- ↑ Evans, Thammy (2006). Great Wall of China: Beijing & Northern China. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 177. ISBN 1-84162-158-7.

- ↑ "Great Wall at Mutianyu". Great Wall of China.

- ↑ Edmonds, Richard Louis (1985). Northern Frontiers of Qing China and Tokugawa Japan: A Comparative Study of Frontier Policy. University of Chicago, Department of Geography; Research Paper No. 213. pp. 38–40. ISBN 0-89065-118-3.

- ↑ Julia Lovell (1 December 2007). The Great Wall: China Against the World, 1000 BC – Ad 2000. Grove. p. 254. ISBN 978-1-55584-832-3.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Mark C. Elliott (2001). The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China. Stanford University Press. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-0-8047-4684-7.

- ↑ Associated Press in Beijing (April 20, 2009). "Great Wall of China longer than believed as 180 missing miles found; Using infrared range finders and GPS devices, official mapping project discovers sections concealed by hills, trenches and rivers,' Guardian.co.uk, April 20, 2009". Guardian (UK). Retrieved July 31, 2010.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 H. A. R. Gibb and C. F. Beckingham, trans. The Travels of Ibn Baṭṭūṭa, A.D. 1325–1354 (Vol. IV). London: Hakluyt Society, 1994 (ISBN 0904180379), pg. 896

- ↑ João de Barros, Ásia de João de Barros. Dos feitos que os portugueses fizeram no descobrimento dos mares e terras do Oriente., 3-a Década. Book 2, Chapter VII. Lisbon, 1563. This chapter is reproduced on pp. 186—204 of the 5th volume of the 1777 edition of Asia.

- ↑ See e.g.: Donald F. Lach (1965). Asia in the making of Europe. I, Book Two. The University of Chicago Press. p. 739

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 28.4 Arthur Waldron, The Great Wall of China: From History to Myth, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990, p. 204-205.

- ↑ Yule, Sir Henry, ed. (1866). Cathay and the way thither: being a collection of medieval notices of China. Issues 36–37 of Works issued by the Hakluyt Society. Printed for the Hakluyt society. p. 579 (This section is the report of Góis' travel, as reported by Matteo Ricci in De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas (published 1615), annotated by Henry Yule)

- ↑ William Lindesay (2008). The Great Wall Revisited: From the Jade Gate to Old Dragon's Head. Harvard University Press. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-674-03149-4.

- ↑ "Jiaoshan Great Wall". TravelChinaGuide.com. Retrieved September 15, 2010. "Jiaoshan Great Wall is located about 3 km (1.9 mi) from Shanhaiguan ancient city. It is named after Jiaoshan Mountain, which is the highest peak to the north of Shanhaiguan Pass and also the first mountain the Great Wall climbs up after Shanhaiguan Pass. Therefore Jiaoshan Mountain is noted as "The first mountain of the Great Wall"."

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Stephen R. Turnbull (January 2007). The Great Wall of China 221 BC-AD 164. Osprey Publishing. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-84603-004-8.

- ↑ Ford, Peter (2006, Nov 30). New law to keep China's Wall looking great. Christian Science Monitor, Asia Pacific section. Retrieved March 17, 2007.

- ↑ Bruce G. Doar: The Great Wall of China: Tangible, Intangible and Destructible. China Heritage Newsletter, China Heritage Project, Australian National University

- ↑ "China's Wall becoming less and less Great". Reuters. August 29, 2007. Retrieved August 30, 2007.

- ↑ "Section of China's Great Wall collapses in heavy rains". 10-08-2012.

- ↑ The Family Memoirs of the Rev. William Stukeley (1887) Vol. 3, p. 142. (1754).

- ↑ Norman, Henry, The Peoples and Politics of the Far East, p. 215. (1895).

- ↑ "How is Great Wall of China from Space?"

- ↑ "The Great Wall of China, Ripley's Believe It or Not, 1932.

- ↑ Urban Legends.com website. Accessed May 12, 2010.

"Can you see the Great Wall of China from the moon or outer space?", Answers.com. Accessed May 12, 2010.

Cecil Adams, "Is the Great wall of China the only manmade object byou can see from space?", The Straight Dope. Accessed May 12, 2010.

Snopes, "Great wall from space", last updated July 21, 2007. Accessed May 12, 2010.

"Is China's Great Wall Visible from Space?", Scientific American, February 21, 2008. "... the wall is only visible from low orbit under a specific set of weather and lighting conditions. And many other structures that are less spectacular from an earthly vantage point—desert roads, for example—appear more prominent from an orbital perspective." - ↑ "Metro Tescos", The Times (London), April 26, 2010. Found at The Times website. Accessed May 12, 2010.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 43.3 Norberto López-Gil (2008). "Is it Really Possible to See the Great Wall of China from Space with a Naked Eye?". Journal of Optometry 1 (1): 3–4. doi:10.3921/joptom.2008.3.

- ↑ "NASA – Great Wall of China". Nasa.gov. Retrieved July 31, 2010.

- ↑ "Interview Transcript" (PDF). Retrieved July 31, 2010.

- ↑ Markus, Francis. (2005, April 19). Great Wall visible in space photo. BBC News, Asia-Pacific section. Retrieved March 17, 2007.

Further reading

- Arnold, H.J.P, "The Great Wall: Is It or Isn't It?" Astronomy Now, 1995.

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (2009): Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13589-2.

- Hessler, Peter. "Walking the Wall". The New Yorker, May 21, 2007, pp. 56–65.

- Luo, Zewen, et al. and Baker, David, ed. (1981). The Great Wall. Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill Book Company (UK). ISBN 070707456

- Man, John. (2008). The Great Wall. London: Bantam Press. 335 pages. ISBN 978-0-593-05574-8.

- Michaud, Roland and Sabrina (photographers), & Michel Jan, The Great Wall of China. Abbeville Press, 2001. ISBN 0-7892-0736-2

- Rojas, Carlos. The Great Wall: A Cultural History (Harvard University Press; 2010) 213 pages; traces the history and considers its imagery in literature, art, and other realms.

- Schafer, Edward H. (1985) The Golden Peaches of Samarkand. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05462-2.

- Yamashita, Michael; Lindesay, William (2007). The Great Wall — From Beginning to End. New York: Sterling. 160 pages. ISBN 978-1-4027-3160-0.

External links

| Find more about Great Wall of China at Wikipedia's sister projects | |

| |

Definitions and translations from Wiktionary |

| |

Media from Commons |

| |

Quotations from Wikiquote |

| |

Source texts from Wikisource |

| |

Textbooks from Wikibooks |

| |

Travel information from Wikivoyage |

| |

Learning resources from Wikiversity |

- International Friends of the Great Wall – organization focused on conservation

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre profile

- Enthusiast/scholar website (Chinese)

- Great Wall of China on In Our Time at the BBC. (listen now)