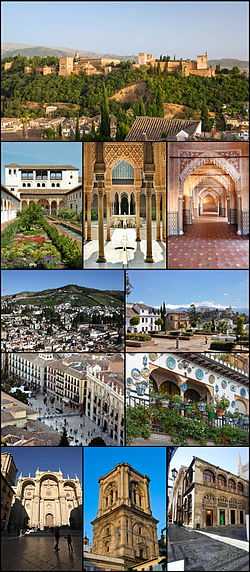

Granada

| Granada | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| City | |||

| |||

| |||

Granada | |||

| Coordinates: 37°10′41″N 3°36′03″W / 37.17806°N 3.60083°WCoordinates: 37°10′41″N 3°36′03″W / 37.17806°N 3.60083°W | |||

| Country | Spain | ||

| Autonomous Community | Andalusia | ||

| Province | Granada | ||

| Comarca | Vega de Granada | ||

| Government | |||

| • Type | Mayor-council | ||

| • Body | Ayuntamiento de Granada | ||

| • Mayor | José Torres Hurtado (PP) | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 88 km2 (34 sq mi) | ||

| Elevation(AMSL) | 738 m (2,421 ft) | ||

| Population (2007) | |||

| • Total | 237,929 | ||

| • Density | 2,700/km2 (7,000/sq mi) | ||

| Demonym |

granadino (m), granadina (f) iliberitano (m), iliberitana (f) granadí, garnatí | ||

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | ||

| Postal code | 18000 | ||

| Area code(s) | +34 (Spain) + (Granada) | ||

| Website | Official website | ||

Granada (Spanish pronunciation: [ɡɾaˈnaða]; Arabic: غرناطة, DIN: Gharnaṭah, Greek: Ἐλιβύργη Elibyrge (Steph. Byz.); Latin: Illiberis (Ptol. ii. 4. § 11) or Illiberi Liberini (Pliny iii. 1. s. 3)) is a city and the capital of the province of Granada, in the autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. Granada is located at the foot of the Sierra Nevada mountains, at the confluence of four rivers, the Beiro, the Darro, the Genil and the Monachil. It sits at an elevation of 738 metres above sea level, yet is only one hour by car from the Mediterranean coast, the Costa Tropical. Nearby is the Sierra Nevada Ski Station, where the FIS Alpine World Ski Championships 1996 were held.

In the 2005 national census, the population of the city of Granada proper was 236,982, and the population of the entire urban area was estimated to be 472,638, ranking as the 13th-largest urban area of Spain. About 3.3% of the population did not hold Spanish citizenship, the largest number of these people (31%) coming from South America. Its nearest airport is Federico García Lorca Granada-Jaén Airport.

The Alhambra, a Moorish citadel and palace, is in Granada. It is the most renowned building of the Andalusian Islamic historical legacy with its many cultural attractions that make Granada a popular destination among the touristic cities of Spain. The Almohad influence on architecture is preserved in the area of the city called the Albaicín with its fine examples of Moorish and Morisco construction. Granada is also well-known within Spain for the prestigious University of Granada which has about 80,000 students spread over five different campuses in the city. The pomegranate (in Spanish, granada) is the heraldic device of Granada.

History

Early history

The region surrounding Granada has been populated by Iberians from at least the 8th century B.C. The region has furthermore experienced Phoenician, Greek, Punic, Roman and Visigothic influences. The Iberians called the wide region Ilturir. On the site of present day Granada there seems to have existed a Roman settlement, but no definitive proof has been found. Some 20 miles south of the modern city, the Iberians built the settlement of Elibyrge in the 5th century BC which later became the Roman city of Illiberis.[1]

Illiberis has traditionally been interpreted as a Basque formation meaning "new town" (Ancient Basque *ili-berri, cf. Modern Basque iri-berri);[2] however, Granada is very far from the regions known to have been Basque-speaking in antiquity (around the Pyrenees, largely as in the modern era), and if the resemblance is not simply a coincidence (the name is given as Iliberris in some modern accounts, with a single L and a double R, which could be a mistake unconsciously bringing the name closer to Basque), the town may have been a Basque colony.[3]

Founding

Granada's historical name in the Arabic language was غرناطة (Ġarnāṭah ). In 711, the Moors, after the Umayyad conquest of Hispania, conquered large parts of the Iberian Peninsula, thus establishing Al-Andalus (Moorish Spain). Meanwhile, Jewish people had established a small community some twenty miles north of Illiberis, called Gárnata or Gárnata al-yahūd ("Granada of the Jews"). The word Gárnata (or Karnattah) possibly means "Hill of Strangers".[4] In 1066, much of the city's Jewish population was massacred.[5]

The actual founding of present day Granada took place in the 11th century, during a civil war that ended the Caliphate in the early 11th century. In the aftermath of these wars, the Berber general Ziri ibn Manad established an independent kingdom for himself, with Elvira as its capital. Because the city was situated on a low plain and, as a result, difficult to protect from attacks, the Zirid ruler decided to transfer his residence to the higher situated hamlet of Gárnata. In a short time this village was transformed into one of the most important cities of Al-Andalus. By the end of the 11th century, the city had spread across the Darro to reach the hill of the future Alhambra, and included the Albayzín (also Albaicín or El Albaicín) neighborhood (a world heritage site). The Almoravid and Almohad dynasties ruled Granada in this period.

Nasrid Dynasty—Emirate of Granada

In 1228, with the departure of the Almohad prince, Idris, who left Iberia to take the Almohad leadership, the ambitious Ibn al-Ahmar established the longest lasting Muslim dynasty on the Iberian peninsula - the Nasrids. With the Reconquista in full swing after the conquest of Cordoba in 1236, the Nasrids aligned themselves with Ferdinand III of Castile, officially becoming the Emirate of Granada in 1238. According to some historians, Granada was a tributary state to the Kingdom of Castile since that year. It provided connections with the Muslim and Arab trade centers, particularly for gold from sub-Saharan Africa and the Maghreb. The Nasrids also supplied troops for Castile, from the Emirate and mercenaries from North Africa.

Ibn Batuta, a famous traveler and an authentic historian, visited the kingdom of Granada in 1350. He described it as a powerful and self-sufficient kingdom in its own right, although frequently embroiled in skirmishes with the kingdom of Castile. If it was really a vassal state, it was contrary to the policy of the Reconquista to allow it to flourish for almost two centuries and a half after the fall of Sevilla in 1248.

Reconquista and the 16th century

On January 2, 1492, the last Muslim ruler in Iberia, Emir Muhammad XII, known as Boabdil to the Spanish, surrendered complete control of the Emirate of Granada to Ferdinand II and Isabella I, Los Reyes Católicos ('The Catholic Monarchs'), after the last battle of the Granada War.

The 1492 surrender of the Islamic Emirate of Granada to the Catholic Monarchs is one of the most significant events in Granada's history as it marks the completion of the Reconquista of Al-Andalus. The terms of the surrender, expressed in the Alhambra Decree treaty, explicitly allowed the city's Muslim inhabitants to continue unmolested in the practice of their faith and customs, known as Mudéjar. By 1499, however, Cardinal Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros grew frustrated with the slow pace of the efforts of Granada's first Archbishop, Fernando de Talavera, to convert non-Christians to Christianity and undertook a program of forced Christian baptisms, creating the Converso (convert) class for Muslims and Jews. Cisneros's new tactics, which were a direct violation of the terms of the treaty, provoked an armed Muslim revolt centered in the rural Alpujarras region southwest of the city.

Responding to the rebellion of 1501, the Castilian Crown rescinded the Alhambra Decree treaty, and mandated that Granada's Muslims must convert or emigrate. Under the 1492 Alhambra Decree, Spain's Jewish population, unlike the Muslims, had already been forced to convert under threat of expulsion or even execution, becoming Marranos (meaning "pigs" in Spanish), or Catholics of Jewish descent. Many of the elite Muslim class subsequently emigrated to North Africa. The majority of the Granada's Mudéjar Muslims stayed to convert, however, becoming Moriscos, or Catholics of Moorish descent ("Moor" being equivalent to Muslim). Both populations of conversos were subject to persecution, execution, or exile, and each had cells that practiced their original religion in secrecy.

Over the course of the 16th century, Granada took on an ever more Catholic and Castilian character, as immigrants came to the city from other parts of the Iberian Peninsula. The city's mosques were converted to Christian churches or completely destroyed. New structures, such as the cathedral and the Chancillería, or Royal Court of Appeals, transformed the urban landscape. After the 1492 Alhambra decree, which resulted in the majority of Granada's Jewish population being expelled, the Jewish quarter (ghetto) was demolished to make way for new Catholic and Castilian institutions and uses.

Legacy

The fall of Granada has a significant place among the important events that mark the latter half of the Spanish 15th century. It completed the so-called Reconquista (or Christian reconquest) of the eight hundred year-long Islamic rule in the Iberian Peninsula. Spain, now without any major internal territorial conflict, embarked on a great phase of exploration and colonization around the globe. In the same year the sailing expedition of Christopher Columbus resulted in what is usually claimed to be the first European sighting of the New World, although Leif Ericson is often regarded as the first European to land in the New World, 500 years before Christopher Columbus. The resources of the Americas enriched the crown and the country, allowing Isabella I and Ferdinand II to consolidate their rule as Catholic Monarchs of the united kingdoms. Subsequent conquests, and the Spanish colonization of the Americas by the maritime expeditions they commissioned, created the vast Spanish Empire: for a time the largest in the world.

Heritage and monuments

The greatest artistic wealth of Granada is its Spanish-Muslim art — in particular, the compound of the Alhambra and the Generalife. The Generalife is a pleasure palace with attached romantic gardens, remarkable both for its location and layout, as well as for the diversity of its flowers, plants and fountains. The Alhambra is the architectural culmination of the works of Nasrid art that were undertaken in the 13th and 14th centuries, with most of the Alhambra having been built at the time of Yusuf I and Mohammed V, between 1333 and 1354.

At present, the buildings of Granada are typically bourgeois in appearance, with much of the architecture dating from the 19th Century, together with numerous Renaissance and Baroque buildings.

- The Alhambra

The Alhambra is a Nasrid "palace city". It was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1984. It is certainly Granada's most emblematic monument and one of the most visited in Spain. It consists of a defensive zone, the Alcazaba, together with others of a residential and formal state character, the Nasrid Palaces and, lastly, the palace, gardens and orchards of El Generalife.

The Alhambra occupies a small plateau on the southeastern border of the city in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada above the Assabica valley. Some of the buildings may have existed before the arrival of the Moors. The Alhambra as a whole is completely walled, bordered to the north by the valley of the Darro, to the south by the al-Sabika, and to the east of the Cuesta del Rey Chico, which in turn is separated from the Albaicín and Generalife, located in the Cerro del Sol.

In the 11th century the Castle of the Alhambra was developed as a walled town which became a military stronghold that dominated the whole city. But it was in the 13th century, with the arrival of the first monarch of the Nasrid dynasty, Mohammed I ibn Nasr (Mohammed I, 1238–1273), that the royal residence was established in the Alhambra. This marked the beginning of its heyday. The Alhambra became palace, citadel and fortress, and was the residence of the Nasrid sultans and their senior officials, including servants of the court and elite soldiers (13th-14th centuries).

In 1527 Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor demolished part of the architectural complex to build the Palace which bears his name. Although the Catholic Monarchs had already altered some rooms of the Alhambra after the conquest of the city in 1492, Charles V wanted to construct a permanent residence befitting an emperor. Around 1537 he ordered the construction of the Peinador de la Reina, or Queen's dressing room, where his wife Isabel lived, over the Tower of Abu l-Hayyay.

There was a pause in the ongoing maintenance of the Alhambra from the 18th century for almost a hundred years, and during the French domination substantial portions of the fortress were blown apart. The repair, restoration and conservation that continues to this day did not begin until the 19th century. The complex currently includes the Museum of the Alhambra, with objects mainly from the site of the monument itself and the Museum of Fine Arts.[6]

- The Generalife

The Generalife is a garden area attached to the Alhambra which became a place of recreation and rest for the Granadan Muslim kings when they wanted to flee the tedium of official life in the Palace. It occupies the slopes of the hill Cerro del Sol above the ravines of the Genil and the Darro and is visible from vantage points throughout the city. It was conceived as a rural village, consisting of landscaping, gardens and architecture. The palace and gardens were built during the reign of Muhammad III (1302–1309) and redecorated shortly after by Abu I-Walid Isma'il (1313–1324). It is of the Islamic Nasrid style, and is today one of the biggest attractions in the city of Granada. The Generalife was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1984.

It is difficult to know the original appearance of the Generalife, as it has been subject to modifications and reconstructions throughout the Christian period which disfigured many of its former aspects. All buildings of the Generalife are of solid construction, and the overall decor is austere and simple. There is little variety to the Alhambra's decorative plaster, but the aesthetic is tasteful and extremely delicate. In the last third of the 20th century, a part of the garden was destroyed to build an auditorium.[7]

- Cathedral

The cathedral of Granada is built over the Nasrid Great Mosque of Granada, in the center of the city. Its construction began during the Spanish Renaissance in the early 16th century, shortly after the conquest of Granada by the Catholic Monarchs, who commissioned the works to Juan Gil de Hontañón and Enrique Egas. Numerous grand buildings were built in the reign of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, so that the cathedral is contemporary to the Christian palace of the Alhambra, the University and the Real Chancillería (supreme court).

The church was conceived on the model of the Cathedral of Toledo, for what initially was a Gothic architectural project, as was customary in Spain in the early decades of the 16th century. However, Egas was relieved by the Catholic hierarchy in 1529, and the continuation of the work was assigned to Diego Siloe, who built upon the example of his predecessor, but changed the approach towards a fully Renaissance aesthetic.[8]

The architect drew new Renaissance lines for the whole building over the Gothic foundations, with an ambulatory and five naves instead of the usual three. Over time, the bishopric continued to commission new architectural projects of importance, such as the redesign of the main façade, undertaken in 1664 by Alonso Cano (1601–1667) to introduce Baroque elements. In 1706 Francisco de Hurtado Izquierdo and later his collaborator José Bada built the current tabernacle of the cathedral.

Highlights of the church's components include the Main chapel, where may be found the praying statues of the Catholic Monarchs, which consists of a series of Corinthian columns with the entablature resting on their capitals, and the vault over all. The spaces of the walls between the columns are perforated by a series of windows. The design of the tabernacle of 1706 preserves the classic proportions of the church, with its multiple columns crossing the forms of Diego de Siloé.[9]

- Royal Chapel

The Catholic Monarchs chose the city of Granada as their burial site by a royal decree dated September 13, 1504. The Royal Chapel of Granada, built over the former terrace of the Great Mosque, ranks with other important Granadan buildings such as the Lonja and the Catedral e Iglesia del Sagrario. In it are buried the Catholic Monarchs, their daughter Joanna of Castile and Philip I of Castile. Construction of the Chapel started in 1505, directed by its designer, Enrique Egas. Built in several stages, the continuing evolution of its design joined Gothic construction and decoration with Renaissance ideals, as seen in the tombs and the 17th and 18th century Granadan art in the Chapel of Santa Cruz. Over the years the church acquired a treasury of works of art, liturgical objects and relics.

The Royal Chapel was declared a Historic Artistic Monument on May 19, 1884, taking consideration of B.I.C. (Bien de Interés Cultural) in the current legislation of the Spanish Historical Heritage (Law 16/1985 of 25 June). The most important parts of the chapel are its main retable, grid and vault. In the Sacristy-Museum is the legacy of the Catholic Monarchs. Its art gallery is highlighted by works of the Flemish, Italian and Spanish schools.[10]

-

Hans Memling - Diptych of Granada, left wing:Acceptance of the Cross, h. 1475

-

Rogier van der Weyden - Birth of Christ, 1435-1438

-

Sandro Botticelli - Prayer of the Garden, 1498-1500

- Albayzín

The Albayzín (or Albaicín) is a neighborhood of Al-Andalus origin, much visited by tourists who flock to the city because of its historical associations, architecture, and landscape.

The archeological findings in the area show that it has been inhabited since ancient times. It became more relevant with the arrival of the Zirid dynasty, in 1013, when it was surrounded by defensive walls. It is one of the ancient centers of Granada, like the Alhambra, the Realejo and the Arrabal de Bib-Rambla, in the flat part of the city. Its current extension runs from the walls of the Alcazaba to the cerro of San Miguel and on the other hand, from the Puerta de Guadix to the Alcazaba.

This neighborhood had its greatest development in the Nasrid era, and therefore largely maintains the urban fabric of this period, with narrow streets arranged in an intricate network that extends from the upper area, called San Nicolás, to the river Darro and Calle Elvira, located in Plaza Nueva. The traditional type of housing is the Carmen granadino, consisting of a free house surrounded by a high wall that separates it from the street and includes a small orchard or garden.

In the Muslim era the Albaicín was characterized as the locus of many revolts against the caliphate. At that time it was the residence of craftsmen, industrialists and aristocrats. With the Christian reconquest, it would progressively lose its splendor. The Christians built churches and settled there the Real Chancillería. During the rule of Philip II of Spain, after the rebellion and subsequent expulsion of the Moors, the district was depopulated. In 1994 it was declared a Unesco World Heritage Site.[11] Of its architectural wealth among others include the Ziri walls of the Alcazaba Cadima, the Nasrid walls, the towers of the Alcazaba, the churches of El Salvador (former main mosque), San Cristóbal, San Miguel Alto and the Real Chancillería.[12]

- Sacromonte

The Sacromonte neighborhood is located on the Valparaíso hill, one of several hills that make up Granada. This neighborhood is known as the old neighborhood of the Romani, who settled in Granada after the conquest of the city. It is one of the most picturesque neighborhoods, full of whitewashed caves cut into the rock and used as residences. The sound of strumming guitars may still be heard there in the performance of flamenco cantes and "quejíos", so that over time it has become one of the most popular tourist attractions in Granada.

At the top of this hill is the Abbey of Sacromonte and the College of Sacromonte, founded in the 17th century by the then Archbishop of Granada Pedro de Castro. The Abbey of Sacromonte was built to monitor and guard the relics of the evangelists of Baetica. Since the first findings the area has been a religious pilgrimage destination.[13]

The abbey complex consists of the Catacombs, The Abbey (17th-18th centuries), the Colegio Viejo de San Dionisio Areopagita (17th century) and the Colegio Nuevo (19th century). The interior of the church is simple and small but has numerous excellent works of art, which accentuate the size and rich carving of the Crucificado de Risueño, an object of devotion for the gypsy people, who sing and dance in the procession of Holy Week. The facilities also include a museum, which houses the works acquired by the Foundation.[14]

- Charterhouse

The Charterhouse of Granada is a monastery of cloistered monks, located in what was a farm or Muslim almunia called Aynadamar ('Fountain of the Tears') that had an abundance of water and fruit trees. The initiative to build the monastery in that place was begun by Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba, known as El Gran Capitán. The charterhouse was founded in 1506; construction started ten years later, and continued for the following 300 years.

The Monastery suffered heavy damage during the Peninsular War and lost considerable property in 1837 as a result of the confiscations of Mendizábal. Currently, the monastery belongs to the Carthusians, reporting directly to the Archdiocese of Granada.[15]

The street entrance to the complex is an ornate arch of Plateresque style. Through it one reaches a large courtyard, at the end which is a wide staircase leading to the entrance of the church. The church, of early 16th century style and plan, has three entrances, one for the faithful and the other two for monks and clergy. Its plan has a single nave divided into four sections, highlighting the retables of Juan Sánchez Cotán and the chancel's glass doors, adorned with mother-of-pearl, silver, precious woods and ivory. The presbytery is covered by elliptical vaulting. The main altar, between the chancel arch and the church tabernacle, is gilded wood.

The Church tabernacle and Sancta Santorum is considered a masterpiece of baroque Spanish art in its blend of architecture, painting and sculpture. The dome that covers this area is decorated with frescoes by the Cordovan artist Antonio Palomino (18th century) representing the triumph of the Church Militant, the faith, and religious life.

The courtyard, with galleries of arches on Doric order columns opening on it, is centered by a fountain. The Chapter House of Legos is the oldest building of the monastery (1517). It is rectangular and covered with groin vaulting.[16]

Districts

.JPG)

The Realejo

Realejo was the Jewish district at the time of the Nasride Granada. The Jewish population was so important that Granada was known from the Al-Andalus Country under the name of Granada de los judios (in Arabic, غرناطة اليهود gharnāṭah al-yahūd). It is today a district made up of many Andalusian villas, with gardens opening onto the streets, called Los Carmenes.

The Cartuja

This district contains the Carthusian monastery of the same name: Cartuja. This is an old monastery started in a late Gothic style with Baroque exuberant interior decorations. In this district also, many buildings were created with the extension of the University of Granada.

Bib-Rambla

The toponym existed at the time of the Arabs. Nowadays, Bib-Rambla is a high point for gastronomy, especially in its terraces of restaurants, open on beautiful days. The Arab bazaar (Alcaicería) is made up of several narrow streets, which start from this place and continue as far as the cathedral

Sacromonte

The Sacromonte neighbourhood is located on the extension of the hill of Albaicín, along the Darro River. This area, which became famous by the nineteenth century for its predominantly Gitano inhabitants, is characterized by cave houses, which are dug into the hillside. The area has a reputation as a major center of flamenco song and dance, including the Zambra Gitana, Andalusian dance originating in the Middle East. The zone is a protected cultural environment under the auspices of the Centro de Interpretación del Sacromonte, a cultural center dedicated to the preservation of Gitano cultural forms.

Albayzín

Albayzín (also written as Albaicín), located on a hill on the right bank of the river Darro, is the ancient Moorish quarter of the city and transports the visitor to a unique world: the site of the ancient city of Elvira, so-called before the Zirid Moors renamed it Granada. It housed the artists who went up to build the palaces of Alhambra on the hill facing it. Time allowed its embellishment. Of particular note is the Plaza de San Nicolas (Plaza of St Nicholas) from where a stunning view of the Alhambra can be seen. The artist George Owen Wynne Apperley RA RI (1884–1960) owned houses on both sides of the Placeta de San Nicolás, also known as El Mirador.

Zaidín

This formerly blue collar but now upmarket neighbourhood houses 100,000 residents of Granada, making it the largest neighborhood or 'barrio'. Traditionally populated by gypsies, now many residents are from North and West Africa, China, and many South American countries. Every Saturday morning it hosts a large outdoor market or "mercadillo", where many gypsies come and sell their wares of fruits and vegetables, clothes and shoes, and other odds and ends.

Parks and gardens in Granada

The city of Granada has a significant number of parks and gardens with many historic and popular entailments, between these natural areas are the following:[17]

|

Climate

| Climate data for Granada (Granada Base Aérea, altitude: 690 m) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 12.2 (54) |

14.1 (57.4) |

17.0 (62.6) |

18.8 (65.8) |

23.1 (73.6) |

28.8 (83.8) |

33.5 (92.3) |

33.2 (91.8) |

28.5 (83.3) |

21.9 (71.4) |

16.2 (61.2) |

13.1 (55.6) |

21.7 (71.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 6.8 (44.2) |

8.4 (47.1) |

10.7 (51.3) |

12.6 (54.7) |

16.5 (61.7) |

21.3 (70.3) |

25.3 (77.5) |

25.1 (77.2) |

21.2 (70.2) |

15.7 (60.3) |

10.6 (51.1) |

7.9 (46.2) |

15.2 (59.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 1.3 (34.3) |

2.6 (36.7) |

4.3 (39.7) |

6.4 (43.5) |

9.8 (49.6) |

13.9 (57) |

17.1 (62.8) |

17.1 (62.8) |

14.0 (57.2) |

9.5 (49.1) |

5.1 (41.2) |

2.8 (37) |

8.7 (47.7) |

| Precipitation mm (inches) | 44 (1.73) |

36 (1.42) |

37 (1.46) |

40 (1.57) |

30 (1.18) |

16 (0.63) |

3 (0.12) |

3 (0.12) |

17 (0.67) |

40 (1.57) |

46 (1.81) |

49 (1.93) |

361 (14.21) |

| Avg. precipitation days | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 54 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 161 | 161 | 207 | 215 | 268 | 314 | 348 | 320 | 243 | 203 | 164 | 147 | 2,751 |

| Source: Agencia Estatal de Meteorología[18] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Granada (Granada Airport, altitude: 567 m) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 13.0 (55.4) |

15.3 (59.5) |

18.6 (65.5) |

20.1 (68.2) |

24.6 (76.3) |

30.0 (86) |

34.4 (93.9) |

33.9 (93) |

29.4 (84.9) |

22.7 (72.9) |

17.2 (63) |

13.5 (56.3) |

22.8 (73) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 6.7 (44.1) |

8.5 (47.3) |

11.0 (51.8) |

12.8 (55) |

16.8 (62.2) |

21.4 (70.5) |

24.8 (76.6) |

24.5 (76.1) |

20.9 (69.6) |

15.5 (59.9) |

10.7 (51.3) |

7.6 (45.7) |

15.1 (59.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 0.3 (32.5) |

1.8 (35.2) |

3.4 (38.1) |

5.6 (42.1) |

9.0 (48.2) |

12.9 (55.2) |

15.2 (59.4) |

15.0 (59) |

12.4 (54.3) |

8.2 (46.8) |

4.2 (39.6) |

1.8 (35.2) |

7.5 (45.5) |

| Precipitation mm (inches) | 41 (1.61) |

38 (1.5) |

30 (1.18) |

38 (1.5) |

28 (1.1) |

17 (0.67) |

4 (0.16) |

3 (0.12) |

16 (0.63) |

42 (1.65) |

48 (1.89) |

53 (2.09) |

357 (14.06) |

| Avg. precipitation days | 6 | 6 | 5 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 52 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 165 | 172 | 225 | 231 | 293 | 336 | 373 | 344 | 262 | 215 | 170 | 149 | 2,935 |

| Source: Agencia Estatal de Meteorología[19] | |||||||||||||

.JPG)

Transport

Construction of a light metro network, the Granada metro, began in 2007. It will cross Granada and cover the towns of Albolote, Maracena and Armilla. As of March 2013, the metro is scheduled to open in early 2014. [citation needed]

Sport

Granada has three football teams:

- Granada CF, in La Liga.

Granada has a basketball team:

- CB Granada, in LEB Plata

Skiing:

Twin towns - sister cities

-

Aix-en-Provence, France

Aix-en-Provence, France -

Belo Horizonte, Brazil

Belo Horizonte, Brazil -

Coral Gables, United States[20]

Coral Gables, United States[20] -

Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany

Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany -

Marrakech, Morocco

Marrakech, Morocco -

Sharjah, United Arab Emirates[21]

Sharjah, United Arab Emirates[21] -

Tetuán, Morocco

Tetuán, Morocco -

Sneinton, England

Sneinton, England -

Tlemcen, Algeria

Tlemcen, Algeria

See also

References

- ↑ Trudy Ring; Robert M. Salkin; Sharon La Boda (1995). International Dictionary of Historic Places: Southern Europe. Taylor & Francis. p. 296. ISBN 978-1-884964-02-2. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- ↑ Hualde, José Ignacio; Lakarra, Joseba; Trask, R. Larry (1995). Towards a History of the Basque Language. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing. p. 37. ISBN 90-272-3634-8.

- ↑ Trask, R. Larry (2008), Wheeler, Max W., ed., Etymological Dictionary of Basque (PDF), Falmer, UK: University of Sussex, p. 229, archived from the original on 7 June 2011, retrieved 17 September 2013

- ↑ Adrian Room (2006). Placenames of the World: Origins And Meanings of the Names for 6,600 Countries, Cities, Territories, Natural Features And Historic Sites. McFarland. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-7864-2248-7. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- ↑ Richard Gottheil; Meyer Kayserling. "Granada". Jewish Encyclopedia G (1906 ed.). "More than 1,500 Jewish families, numbering 4,000 persons, fell in one day, Ṭebet 9 (December 30), 1066."

- ↑ "Historical introduction of the Alhambra". Alhambradegranada.org. Retrieved 2011-03-11.

- ↑ "The Generalife". Alhambradegranada.org. Retrieved 2011-03-11.

- ↑ Jerez Mir, Carlos: Architecture guide of Granada, Ministry of Culture of Andalusia, pág. 59, ISBN 84-921824-0-7

- ↑ "Guide of Monuments of Granada: Cathedral". Moebius.es. Retrieved 2011-03-11.

- ↑ "Royal Chapel of Granada. Five hundred years of history". Capillarealgranada.com. Retrieved 2011-03-11.

- ↑ "The Al-Andalus legacy - The Albaicín (History)". Legadoandalusi.es. Retrieved 2011-03-11.

- ↑ "Educational tours -culturals for the Albayzín". Granada-in.com. Retrieved 2011-03-11.

- ↑ "History of the Sacromonte". Guiasdegranada.com. Retrieved 2011-03-11.

- ↑ Hierro Calleja, Rafael - Granada y La Alhambra (The Sacromonte. Page 113) id= ISBN 84-7169-084-5

- ↑ Hierro Calleja, Rafael - Granada y la Alhambra (Charterhouse. Page 178) - Ediciones Miguel Sánchez id= ISBN 84-7169-084-5

- ↑ "History of the Charterhouse of Granada". Legadoandalusi.es. Retrieved 2011-03-11.

- ↑ "Parques y Jardines de Granada". Granadatur.com. Retrieved 2011-03-11.

- ↑ "Valores climatológicos normales. Granada Base Aérea".

- ↑ "Valores climatológicos normales. Granada Aeropuerto".

- ↑ "City of Coral Gables Web Site". Coralgables.com. Retrieved 2010-10-03.

- ↑ "Sultan attends signing of Sharjah-Granada sister city agreement UAE - The Official Web Site - News". Uaeinteract.com. Retrieved 2010-10-03.

- Cortés Peña, Antonio Luis and Bernard Vincent. Historia de Granada. 4 vols. Granada: Editorial Don Quijote, 1983.

- Historia del reino de Granada. 3 vols. Granada: Universidad de Granada, Legado Andalusí, 2000.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1854–57). "article name needed". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: John Murray.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1854–57). "article name needed". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: John Murray.

Further reading

- Published in the 19th century

- Jedidiah Morse; Richard C. Morse (1823), "Granada", A New Universal Gazetteer (4th ed.), New Haven: S. Converse

- Arthur de Capell Brooke (1831), "(Granada)", Sketches in Spain and Morocco, London: Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley, OCLC 13783280

- Richard Ford (1855), "Granada", A Handbook for Travellers in Spain (3rd ed.), London: J. Murray, OCLC 2145740

- John Lomas, ed. (1889), "Granada", O'Shea's Guide to Spain and Portugal (8th ed.), Edinburgh: Adam & Charles Black

- Published in the 20th century

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Granada. |

- City council of Granada

- Website of the Granada Tourist Office

- Timelapse Granada HD

- Granada city guide at HitchHikers Handbook

- English language magazine for the region

- Granada on the Open Directory Project

- Webcam Granada/Alhambra

- ArchNet.org. "Granada". Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: MIT School of Architecture and Planning.

| |||||||

| |||||||