Giuseppe Verdi

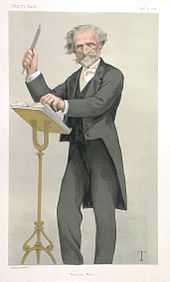

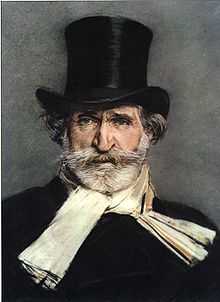

Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi (Italian: [d͡ʒuˈzɛppe ˈverdi]; 9 or 10 October 1813 – 27 January 1901) was an Italian Romantic composer primarily known for his operas. Verdi and Richard Wagner are considered the two preeminent opera composers of the nineteenth century.[1] Verdi dominated the Italian opera scene after the eras of Bellini, Donizetti and Rossini. His works are frequently performed in opera houses throughout the world and, transcending the boundaries of the genre, some of his themes have long since taken root in popular culture, as "La donna è mobile" from Rigoletto, "Libiamo ne' lieti calici" (The Drinking Song) from La traviata, "Va, pensiero" (The Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves) from Nabucco, the "Coro di zingari" (Anvil Chorus) from Il trovatore and the "Grand March" from Aida.

Moved by the death of compatriot Alessandro Manzoni, Verdi wrote Messa da Requiem in 1874 in Manzoni's honour, a work now regarded as a masterpiece of the oratorio tradition and a testimony to his capacity outside the field of opera.[2] Visionary and politically engaged, he remains – alongside Garibaldi and Cavour – an emblematic figure of the reunification process of the Italian peninsula (the Risorgimento).

Biography

Early life

Verdi was born the son of Carlo Giuseppe Verdi and Luigia Uttini in Le Roncole, a village near Busseto, then in the Département Taro, which was a part of the First French Empire after the annexation of the Duchy of Parma and Piacenza. The baptismal register, on 11 October lists him as being "born yesterday", but since days were often considered to begin at sunset, this could have meant either 9 or 10 October. The next day, he was baptized in the Roman Catholic Church in Latin as Joseph Fortuninus Franciscus. The day after that (Tuesday), Verdi's father took his newborn the three miles to Busseto, where the baby was recorded as Joseph Fortunin François; the clerk wrote in French. "So it happened that for the civil and temporal world Verdi was born a Frenchman."[3]

When he was still a child, Verdi's parents moved from Le Roncole to Busseto, where the future composer's education was greatly facilitated by visits to the large library belonging to the local Jesuit school. It was in Busseto that Verdi was given his first lessons in composition.

Verdi went to Milan when he was twenty to continue his studies. He took private lessons in counterpoint while attending operatic performances and concerts, often of specifically German music. Milan's beaumonde association convinced him that he should pursue a career as a theatre composer. During the mid-1830s, he attended the Salotto Maffei salons in Milan, hosted by Clara Maffei.

Returning to Busseto, he became the town music master and gave his first public performance in 1830 in the home of Antonio Barezzi, a local merchant and music lover who had long supported Verdi's musical ambitions in Milan.

Because he loved Verdi's music, Barezzi invited Verdi to be his daughter Margherita's music teacher, and the two soon fell deeply in love. They were married on 4 May 1836, and Margherita gave birth to two children, Virginia Maria Luigia (26 March 1837 – 12 August 1838) and Icilio Romano (11 July 1838 – 22 October 1839). Both died in infancy while Verdi was working on his first opera and, shortly afterwards, Margherita died of encephalitis[4][5] on 18 June 1840, aged only 26.[6] Verdi adored his wife and children and was devastated by their deaths.

Initial recognition

The production by Milan's La Scala of his first opera, Oberto, in November 1839 achieved a degree of success, after which Bartolomeo Merelli, La Scala's impresario, offered Verdi a contract for three more works.[7]

It was while he was working on his second opera, Un giorno di regno, that Verdi's wife died. The opera, given in September 1840, was a flop and he fell into despair and vowed to give up musical composition forever. However, Merelli persuaded him to write Nabucco, and its opening performance in March 1842 made Verdi famous. Legend (and Verdi's own "An Autobiographical Sketch" of 1879[8]) has it that it was the words of the famous "Va, pensiero" chorus of the Hebrew slaves that inspired him to write music again.

|

"O sommo Carlo"

Ernani (1844), act 3, sung by Mattia Battistini, Emilia Corsi, Luigi Colazza, Aristodemo Sillich, and the La Scala chorus in 1906

|

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

A period of hard work – producing 14 operas in all – followed in the fifteen years after 1843, right up through the composition of Un ballo in maschera, a period which Verdi was to describe as his "years in the galleys" in a letter to Countess Clara Maffei: "From Nabucco, you may say, I have never had one hour of peace. Sixteen years in the galleys".[9][10] These included his I Lombardi in 1843, and Ernani in 1844. For some , the most original and important opera that Verdi wrote is Macbeth (1847). It was Verdi's first attempt to write an opera without a love story, breaking a basic convention of 19th-century Italian opera.

In 1847, I Lombardi, which was revised and renamed Jérusalem, was produced by the Paris Opera. Due to a number of Parisian conventions that had to be honored (including extensive ballets), it became Verdi's first work in the French Grand opera style.

Middle years

|

Quartet "Bella figlia dell'amore"

Rigoletto (1851), act 3. A 1907 Victor Records recording with Enrico Caruso, Bessie Abott, Louise Homer and Antonio Scotti.

|

| Problems playing these files? See media help. | |

Sometime in the mid-1840s, after the death of Margherita Barezzi, Verdi "formed a lasting attachment to the soprano Giuseppina Strepponi who was to become his lifelong companion",[11] but she was in the twilight of her career. Their cohabitation before marriage was regarded as scandalous in some of the places they lived, but Verdi and Giuseppina married on 29 August 1859 at Collonges-sous-Salève, in the Kingdom of Piemonte, near Geneva.[12] In 1848, while living in Busseto with Strepponi, Verdi bought an estate two miles from the town. Initially, his parents lived there, but after his mother's death in 1851, he made the Villa Verdi at Sant'Agata in Villanova sull'Arda his home, which it remained until his death.

As he was still laboring through his "years in the galleys",[9] Verdi created one of his greatest masterpieces, Rigoletto, which premiered in Venice in 1851. Based on a play by Victor Hugo (Le roi s'amuse), the libretto had to undergo substantial revisions in order to satisfy the epoch's censorship, and the composer was on the verge of giving it all up a number of times. The opera quickly became a great success.

With Rigoletto, Verdi sets up his original idea of musical drama as a cocktail of heterogeneous elements, embodying social and cultural complexity, and beginning from a distinctive mixture of comedy and tragedy. Rigoletto's musical range includes band-music such as the first scene or the aria "La donna è mobile", Italian melody such as the famous quartet "Bella figlia dell'amore", chamber music such as the duet between Rigoletto and Sparafucile and powerful and concise declamatos often based on key-notes like the C and C# notes in Rigoletto and Monterone's upper register.

There followed the second and third of the three major operas of Verdi's "middle period": in 1853 Il trovatore was produced in Rome and La traviata in Venice. The latter was based on Alexandre Dumas, fils' play The Lady of the Camellias, and became the most popular of all Verdi's operas, placing first in the Operabase list of most performed operas worldwide.[13]

Later compositions

|

"È scherzo od è follia"

Un ballo in maschera (1859), act 1, scene 2. Performed by Enrico Caruso, Frieda Hempel, Maria Duchêne, Andrés de Segurola and Léon Rothier.

"Nè gustare m'è dato un'ora..."

|

| Problems playing these files? See media help. | |

Between 1855 and 1867 there was an outpouring of great Verdi operas, among them such repertory staples as Un ballo in maschera (1859), La forza del destino (commissioned by the Imperial Theatre of Saint Petersburg for 1861 but not performed until 1862), and a revised version of Macbeth (1865). Other somewhat less often performed include Les vêpres siciliennes (1855) and Don Carlos (1867), both commissioned by the Paris Opera and initially given in French. Today, these latter two operas are most often performed in Italian translation. Simon Boccanegra was composed in 1857.

In 1869, Verdi was asked to compose a section for a requiem mass in memory of Gioachino Rossini which was to be a collection of sections composed by other Italian contemporaries of Rossini. The requiem was compiled and completed, but was cancelled at the last minute (and was not performed in Verdi's lifetime). Verdi blamed this on the lack of enthusiasm for the project by the intended conductor, Angelo Mariani, who had been a longtime friend of his. The episode led to a permanent break in their personal relations. The soprano Teresa Stolz (who later had a strong professional – and, perhaps, romantic – relationship with Verdi) was at that time engaged to be married to Mariani, but she left him not long after. Five years later, Verdi reworked his "Libera Me" section of the Rossini Requiem and made it a part of his Requiem Mass, honoring the famous novelist and poet Alessandro Manzoni, who had died in 1873. The complete Requiem was first performed at the cathedral in Milan on 22 May 1874.

Verdi's grand opera, Aida, is sometimes thought to have been commissioned for the celebration of the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, and the Khedive had planned to inaugurate an opera house as part of the canal opening festivities, but according to Julian Budden,[14] Verdi turned down the Khedive's invitation to write an "ode" for the new opera house because "I am not accustomed to compose morceaux de circonstance.[15] The opera house actually opened with a production of Rigoletto. Later, in 1869/70, the organizers again approached Verdi (this time with the idea of writing an opera), but he again turned them down. When they warned him that they would ask Charles Gounod instead and then threatened to engage Richard Wagner's services, Verdi began to show considerable interest, and agreements were signed in June 1870.

Teresa Stolz was associated with both Aida and the Requiem (as well as a number of other Verdi roles). The role of Aida was written for her, and although she did not appear in the world premiere in Cairo in 1871, she created Aida in the European premiere in Milan in February 1872. She was also the soprano soloist in the first and many later performances of the Requiem. It was widely believed that she and Verdi had an affair after she left Angelo Mariani, and a Florence newspaper criticised them for this in five strongly worded articles. Whether there is any truth to the accusation may never be known with any certainty. However, after Giuseppina Strepponi's death, Teresa Stolz became a close companion of Verdi until his own death.

Verdi and Wagner never met. Verdi's comments on Wagner and his music are few and hardly benevolent ("He invariably chooses, unnecessarily, the untrodden path, attempting to fly where a rational person would walk with better results"), but at least one of them is kind: upon learning of Wagner's death, Verdi lamented, "Sad, sad, sad! ... a name that will leave a most powerful impression on the history of art."[16] Of Wagner's comments on Verdi, only one is well-known. After listening to Verdi's Requiem, the German, prolific and eloquent in his comments on some other composers, stated, "It would be best not to say anything."[citation needed]

Last years

|

|

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

During the following years, Verdi worked on revising some of his earlier scores, most notably new versions of Don Carlos, La forza del destino, and Simon Boccanegra.

Otello, based on William Shakespeare's play, with a libretto written by the younger composer of Mefistofele, Arrigo Boito, premiered in Milan in 1887. Its music is "continuous" and cannot easily be divided into separate "numbers" to be performed in concert. Some feel that although masterfully orchestrated, it lacks the melodic lustre so characteristic of Verdi's earlier, great, operas, while many critics consider it Verdi's greatest tragic opera, containing some of his most beautiful, expressive music and some of his richest characterizations. In addition, it lacks a prelude, something Verdi listeners were not accustomed to. Arturo Toscanini performed as cellist in the orchestra at the world premiere and began his association with Verdi (a composer he revered as highly as Beethoven).

Verdi's last opera, Falstaff, whose libretto was also by Boito, was based on Shakespeare's Merry Wives of Windsor and Henry IV, Part 1 via Victor Hugo's subsequent translation. It was an international success and is one of the supreme comic operas which show Verdi's genius as a contrapuntist.

In 1894, Verdi composed a short ballet for a French production of Otello, his last purely orchestral composition. Years later, Arturo Toscanini recorded the music for RCA Victor with the NBC Symphony Orchestra which complements the 1947 Toscanini performance of the complete opera.

In 1897, Verdi completed his last composition, a setting of the traditional Latin text Stabat Mater. This was the last of four sacred works that Verdi composed, Quattro pezzi sacri, which can be performed together or separately. They were not conceived as a unit and, in fact, Verdi did not want the Ave Maria published, as he considered it an exercise. The first performance of the four works was on 7 April 1898, at the Opéra, Paris. The four works are: Ave Maria for mixed chorus; Stabat Mater for mixed chorus and orchestra; Laudi alla Vergine Maria for female chorus; and Te Deum for double chorus and orchestra.

On 29 July 1900, King Umberto I of Italy was assassinated by Gaetano Bresci, a deed that horrified the aged composer.[17]

While staying at the Grand Hotel et de Milan[18] in Milan, Verdi suffered a stroke on 21 January 1901. He gradually grew more feeble and died nearly a week later, on 27 January. Arturo Toscanini conducted the vast forces of combined orchestras and choirs composed of musicians from throughout Italy at Verdi's funeral service in Milan. To date, it remains the largest public assembly of any event in the history of Italy.[19]

Verdi was initially buried in Milan's Cimitero Monumentale. A month later, his body was moved to the "crypt" of the Casa di Riposo per Musicisti, a rest home for retired musicians that Verdi had recently established. In October 1894, the French government awarded him the Grand-Croix de la Legion d'honneur.[citation needed] He was the first non-French musician to receive the Grand-Croix.[citation needed]

Verdi was an agnostic atheist.[20] Toscanini, in a taped interview, described Verdi as "an atheist",[21] His second wife, Giuseppina Strepponi, described him as "a man of little faith".[22]

Role in the Risorgimento

Music historians have long perpetuated a myth about the famous "Va, pensiero" chorus sung in the third act of Nabucco. The myth claims that, when the "Va, pensiero" chorus was sung in Milan, then belonging to the large part of Italy under Austrian domination, the audience, responding with nationalistic fervor to the exiled slaves' lament for their lost homeland, demanded an encore of the piece. As encores were expressly forbidden by the government at the time, such a gesture would have been extremely significant. However, recent scholarship puts this to rest. Although the audience did indeed demand an encore, it was not for "Va, pensiero" but rather for the hymn Immenso Jehova, sung by the Hebrew slaves to thank God for saving His people. In light of these new revelations, Verdi's position as the musical figurehead of the Risorgimento has been correspondingly downplayed.[23] It is interesting to note in this context that all but seven (his last operas) were created by Verdi whilst Milan, the capital of Lombardo Veneto, was an integral part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.[24]

On the other hand, during rehearsals, workmen in the theater stopped what they were doing during "Va, pensiero" and applauded at the conclusion of this haunting melody[25] while the growth of the "identification of Verdi's music with Italian nationalist politics" is judged to have begun in the summer of 1846 in relation to a chorus from Ernani in which the name of one of its characters, "Carlo", was changed to "Pio", a reference to Pope Pius IX's grant of an amnesty to political prisoners.[26]

Verdi's 14th opera, La battaglia di Legnano, written while Verdi was living in Paris in 1848 (though he quickly traveled to Milan after news of the "Cinque Giornate" arrived there) seems to have been composed specifically as "an opera with a purpose" (as opera historian Charles Osborne describes it), but Osborne continues: "while parts of Verdi's earlier operas had frequently been taken up by the fighters of the Risorgimento ... this time the composer had given the movement its own opera".[27]

After Italy was unified in 1861, many of Verdi's early operas were re-interpreted as Risorgimento works with hidden Revolutionary messages that probably had not been intended by either the composer or librettist. Beginning in Naples in 1859 and spreading throughout Italy, the slogan "Viva VERDI" was used as an acronym for Viva Vittorio Emanuele Re D'Italia (Viva Victor Emmanuel King of Italy), referring to Victor Emmanuel II, then king of Sardinia.[28][29]

The "Chorus of the Hebrews" (the English title for "Va, pensiero") has another appearance in Verdi folklore. Prior to Verdi's body's being driven from the cemetery to the official memorial service and its final resting place at the Casa di Riposo per Musicisti, Arturo Toscanini conducted a chorus of 820 singers in "Va, pensiero". At the Casa, the "Miserere" from Il trovatore was sung.[30]

Verdi was elected as a member of the Chamber of Deputies in 1861 following a request of Prime Minister Cavour but in 1865 he resigned from the office.[31] In 1874 he was named Senator of the Kingdom by King Victor Emmanuel II.

Styles

Verdi's predecessors who influenced his music were Rossini, Bellini, Giacomo Meyerbeer and, most notably, Gaetano Donizetti and Saverio Mercadante. Although respectful of Gounod, Verdi was careful not to learn anything from the Frenchman whom many of Verdi's contemporaries regarded as the greatest living composer. Some strains in Aida suggest at least a superficial familiarity with the works of the Russian composer Mikhail Glinka, whom Franz Liszt, after his tour of the Russian Empire as a pianist, popularized in Western Europe.

Throughout his career, Verdi rarely utilized the high C in his tenor arias, citing the fact that the opportunity to sing that particular note in front of an audience distracts the performer before and after the note appears. However, he did provide high Cs to Duprez in Jérusalem and to Tamberlick in the original version of La forza del destino. The high C, often-heard in the aria "Di quella pira" from Il trovatore, does not appear in Verdi's score.

Verdi himself once said, "Of all composers, past and present, I am the least learned." He hastened to add, however, "I mean that in all seriousness, and by learning I do not mean knowledge of music."

However, it would be incorrect to assume that Verdi underestimated the expressive power of the orchestra or failed to use it to its full capacity where necessary. Moreover, orchestral and contrapuntal innovation is characteristic of his style: for instance, the strings producing a rapid ascending scale in Monterone's scene in Rigoletto accentuate the drama, and, in the same opera, the chorus humming six closely grouped notes backstage portrays, very effectively, the brief ominous wails of the approaching tempest. Verdi's innovations are so distinctive that other composers do not use them; they remain, to this day, some of Verdi's signatures.

Verdi was one of the first composers who insisted on patiently seeking out plots to suit his particular talents. Working closely with his librettists and well aware that dramatic expression was his forte, he made certain that the initial work upon which the libretto was based was stripped of all "unnecessary" detail and "superfluous" participants, and only characters brimming with passion and scenes rich in drama remained.

Many of his operas, especially the later ones from 1851 onwards, are a staple of the standard repertoire. With the possible exception of Giacomo Puccini, no composer of Italian opera has managed to match Verdi's popularity.

Works

Verdi's operas (in Italian unless noted) and their date of première are:

|

|

Legacy

Verdi has been the subject of a number of cultural works. These include the 1938 film directed by Carmine Gallone, Giuseppe Verdi, starring Fosco Giachetti; the 1982 miniseries, The Life of Verdi, directed by Renato Castellani, where Verdi was played by Ronald Pickup, with narration by Burt Lancaster in the English version; and the 1985 play After Aida (a play-with-music similar to Amadeus). He is a character in the 2011 opera, Risorgimento! by Italian composer Lorenzo Ferrero, written to commemorate the 150th anniversary of Italian unification of 1861.

There are three music conservatories, the Milan Conservatory and those in Turin and Como, and many theatres named after Verdi in Italy. There is a Giuseppe Verdi Monument in Verdi Square in Manhattan, in the USA.

The towns of Verdi, Nevada and Verdi, California which straddle the state line were named after Verdi by Charles Crocker, founder of the Central Pacific Railroad, when he pulled a slip of paper from a hat and read the name of the Italian opera composer in 1868.[32] Verdi, Minnesota is named both for the composer and the green fields surrounding the town.[33]

A relatively young impact crater on the planet Mercury was named after Verdi in 1979 by the International Astronomical Union[34] and sometimes called "Joe Green" by NASA.[35]

Verdi's name literally translates as "Joseph Green" in English (although verdi is the plural form of "green"). Musical comedian Victor Borge often referred to the famous composer as "Joe Green" in his act, saying that "Giuseppe Verdi" was merely his "stage name". The same joke-translation is mentioned in Agatha Christie's Evil Under the Sun by Patrick Redfern to Hercule Poirot – a prank which inadvertently gives Poirot the answer to the murder.

See also

- The Life of Verdi, a 1982 television miniseries

References

Notes

- ↑ Paul Levy, "Bob Dylan: Verdi and/or Wagner: Two Men, Two Worlds, Two Centuries by Peter Conrad", The Guardian (London), 13 November 2011. Retrieved 21 June 2013

- ↑ Rosen

- ↑ Martin, p. 3

- ↑ "Giuseppe Verdi: La Vita" on magiadellopera.com (in Italian) notes: "On 18 June 1840 Margherita Barezzi's life was cut short by violent encephalitis."

- ↑ "Giuseppe Verdi: Sommario" on reocities.com (in Italian): "on 20 [sic] June 1840 his young wife Margherita died, struck down by a severe form of acute encephalitis."

- ↑ "Margherita Barezzi" on museocasabarezzi.it (in Italian) notes: "She died the following year [1840] on 18 June, aged only 26 years, while Verdi was working on his ill-fated second opera, Un Giorno di Regno."

- ↑ Budden, vol 1, p. 71

- ↑ Verdi, "An Autobiographival Sketch" (1879) in Werfel and Stefan, pp. 80–93

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Verdi to Clara Maffei, 12 May 1858, in Philips-Matz, p. 379

- ↑ Philip Gossett, "Giuseppe Verdi and the Italian Risorgimento", Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 156, No. 3, September 2012: Gossett notes: "Yet Verdi's only use of the expression is in a letter of 1858 to his Milanese friend Clarina Maffei, where it refers to all his operas through Un ballo in maschera: it laments the social circumstances in which Italian composers worked in the mid-nineteenth century, rather than judging aesthetic value."

- ↑ Parker, p. 934

- ↑ Phillips-Matz, pp.394–95

- ↑ "Opera Statistics, 2012–13" List of Operas on Operabase. Retrieved 21 June 2013

- ↑ Budden, Vol. 3, p. 163

- ↑ Verdi to Draneht Bey, 9 August 1869, in Budden, Vol. 3, footnote, p. 163

- ↑ Schonberg, p. 260

- ↑ Newman, p. 597: "Did he feel himself somehow guilty of at least indirectly causing that assassination? For almost 30 operas he composed throughout his long life, at least half dealt with killings, murder and other sort of violent ends of various personage, including assassination plots against kings, leaders, or men in charge in six of them: Attila, Macbeth, Rigoletto, Les vêpres siciliennes, Simon Boccanegra, and Un ballo in maschera."

- ↑ The hotel's website contains a brief history of the composer's stay and a few photographs of those days

- ↑ Phillips-Matz, p. 764, notes the crowd "estimated at 200,000". In the second part of his 2010 BBC4 series, Opera Italia, on the subject of Verdi's operas, presenter and music director of the Royal Opera House, Antonio Pappano notes the size as being 300,000

- ↑ Balthazar, p. 13: "Verdi sustained his artistic reputation and his personal image in the last years of his life. He never relinquished his anticlerical stance, and his religious belief verged on atheism. Strepponi described him as not much of a believer and complained that he mocked her religious faith. Yet he summoned the creative strength to write the Messa da Requiem (1874) to honor Manzoni, his "secular saint," and conduct its world premiere."

- ↑ Toscanini, p. 262: "I've asked you whether you're religious, whether you believe! I do—I believe—I'm not an atheist like Verdi, but I don't have time to go into the subject."

- ↑ Tintori, p. 232.

- ↑ Casini, ?

- ↑ Roger Parker, "Il vate del Risorgimento: Nabucco e il "Va Pensiero" in Degrada,

- ↑ Phillips-Matz, p. 116

- ↑ Phillips-Matz, pp. 188–191

- ↑ Osborne, p. 198

- ↑ Parker, p. 942

- ↑ Budden, Vol. 3, p. 80

- ↑ Phillips-Matz, p. 765

- ↑ "Giuseppe Verdi politico e deputato, Cavour, il Risorgimento" on liberalsocialisti.org (in Italian) Retrieved 2 January 2010

- ↑ "A Brief History of Verdi", Verdi History Center

- ↑ Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society. Minnesota Historical Society. 1920. pp. 309–.

- ↑ "Nomenclature: Mercury, craters". IAU. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- ↑ "Meet Joe Green". NASA. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

Cited sources

- Balthazar, Scott E. (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Verdi, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0-521-63535-6

- Budden, Julian (1973). The Operas of Verdi, Volume I (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-816261-8.

- Budden, Julian (1973). The Operas of Verdi, Volume II (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-816262-6.

- Budden, J. (1973). The Operas of Verdi, Volume III (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-816263-4.

- Casini, Claudio, Verdi, Milan: Rusconi, 1982 ISBN 978-88-18-70061-9 (in Italian); Königstein: Athenäum, 1985 ISBN 3-7610-8377-7 (in German)

- Delgrada, Francesco, (Ed.), Giuseppe Verdi: l'uomo, l'opera, il mito, Milan, Skira, 2000. ISBN 88-8118-816-3 ISBN 978-88-8118-816-1 (Catalogue from an exhibition at the Palazzo Reale, 2000–2001)

- De Van, Gilles (trans. Gilda Roberts), Verdi's Theater: Creating Drama Through Music. Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press, 1998 ISBN 0-226-14369-4 (hardback), ISBN 0-226-14370-8

- Hunt, Lynn (2009). The Making of the West (3rd ed.). Bedford/St. Martin's. ISBN 0-312-46510-6.

- Martin, George, Verdi: His Music, Life and Times, New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1986 ISBN 0-396-08196-7 (paper, 1983)

- Newman, Earnest, Stories of the Great Operas. Philadelphia: The Blakinson Company, 1930

- Osborne, Charles, The Complete Opera of Verdi, New York: Da Capo Press, Inc., 1969. ISBN 0-306-80072-1

- Parker, Roger, "Verdi, Giuseppe" in Stanley Sadie, (Ed.), The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, Vol. Four. London: MacMillan Publishers, Inc. 1998 ISBN 0-333-73432-7 ISBN 1-56159-228-5

- Phillips-Matz, Mary Jane, Verdi: A Biography, London & New York: Oxford University Press, 1993 ISBN 0-19-313204-4

- Rosen, David (1995), Verdi: Requiem, Cambridge: Cambridge Music Handbooks. ISBN 978-0-521-39767-4

- Schonberg, Harold C. (1997). 's+death+verdi The Lives of the Great Composers. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-03857-2. Retrieved 9 January 2008

- Tintori, Giampiero, Guida all'ascolto di Giuseppe Verdi, Milano: Mursia, 1983.

- Toscanini, Arturo (Ed. Harvey Sachs), The letters of Arturo Toscanini, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2002 ISBN 978-0-375-40405-4

- Walker, Frank, The Man Verdi, New York: Knopf, 1962, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982 ISBN 0-226-87132-0

- Werfel, Franz and Stefan, Paul, Verdi: The Man and His Letters, New York: Vienna House 1973 ISBN 0-8443-0088-8

Other sources

- Budden, Julian (2008). Verdi (3rd edition). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-532342-9.

- Kamien, R. (1997). Music: an appreciation – student brief (3rd ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-07-036521-0.

- Gal, H. (1975). Brahms, Wagner, Verdi: Drei Meister, drei Welten. Fischer. ISBN 3-10-024302-1.

- Harwood, Gregory W. (1998). Giuseppe Verdi: A Guide to Research. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-8240-4117-5.

- Harwood, Gregory (2012). Giuseppe Verdi: A Research and Information Guide (2d ed.). Abingdon (New York); Routledge (UK). ISBN 0-415-88189-7.

- Marvin, Roberta Montemorra (ed.) (2013 & 2014), The Cambridge Verdi Encyclopedia, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-51962-5. e-book: December 2013 / Hardcover: January 2014

- Michels, Ulrich (1992). dtv-Atlas zur Musik: Band Zwei (7th ed.). Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag. ISBN 3-423-03023-2.

- Newark, Cormac, "Scenic Dispositions: Verdi's changing attitude to opera production", Opera (London), December 2013, Volume 64, No. 12, pp. 1557–1562.

- Polo, Claudia (2004), Immaginari verdiani. Opera, media e industria culturale nell'Italia del XX secolo, Milano: BMG/Ricordi. (Italian)

Verdi's life in and around Busseto

- Associazione Amici di Verdi (ed.), Con Verdi nella sua terra, Busseto, 1997 (in English)

- Maestrelli, Maurizio, Guida alla Villa e al Parco (in Italian), publication of Villa Verdi, 2001

- Mordacci, Alessandra, An Itinerary of the History and Art in the Places of Verdi, Busseto: Busseto Tourist Office, 2001 (in English)

- Villa Verdi: the Visit and Villa Verdi: The Park; the Villa; the Room (pamphlets in English), publications of the Villa Verdi

External links

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Giuseppe Verdi |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Giuseppe Verdi. |

- Giuseppe Verdi Official Site

- National Museum Giuseppe Verdi - Busseto

- Stanford University list of Verdi operas, premiere locations and dates, etc.

- Works by Giuseppe Verdi at Project Gutenberg

- "Album Verdi" from the Digital Library of the National Library of Naples (Italy)

- Free scores by Verdi at the International Music Score Library Project

- Free scores by Giuseppe Verdi in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- The Mutopia Project has compositions by Giuseppe Verdi

- Works by or about Giuseppe Verdi in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Detailed listing of "complete" recordings of Verdi's operas and of extended excerpts

- "Verdi and Milan", lecture by Roger Parker on Verdi, given at Gresham College, London 14 May 2007

- Verdi cylinder recordings, from the Cylinder Preservation and Digitization Project at the University of California, Santa Barbara Library

- 200th Anniversary Festival in Edmonton, Canada to celebrate Giuseppe Verdi's birth

- The website of the first iPhone and iPad app about Giuseppe Verdi and Milan, created with the patronage of the Municipality and the Province of Milan

| |||||||||||||||||

|