Giovanni Caselli

| Giovanni Caselli | |

|---|---|

Giovanni Caselli | |

| Born |

25 April 1815 Siena, Italy[1] |

| Died |

8 June 1891 Florence, Italy |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Education | University of Florence |

| Occupation | inventor |

| Known for | pantelegraph |

Giovanni Caselli (1815–1891) was an Italian physicist.[2][3] He is the inventor of the pantelegraph (a.k.a. Universal Telegraph or "all-purpose telegraph"), the predecessor of the modern fax machine.[4][5] The world's first practical operating facsimile machine ("fax") system put into use was by Caselli.[6][7][8]

Biography

At the beginning of his career he was studying literature, history, science and religion.[9] Caselli was appointed a member dell'Ateneo Italian.[9] Besides his interest in science and physics he studied to become a Catholic priest.[10] In 1836 Caselli was ordained.[1]

In 1841 he went to Parma in the Province of Modena to become a tutor for the sons of Count Marquis Sanvitale of Modena. In 1849 he participated in the riots and voted for annexation of the Duchy of Modena to the Kingdom of Sardinia. Because of this he was forced out of Modena whereupon he returned to Florence.[2] In that year he became a professor of physics at the University of Florence.[1]

In Florence he studied physics under Leopoldo Nobili.[2] These studies involved electrochemistry, electromagnetism, electricity and magnetism.[2] Caselli started a journal called "The Recreation" in 1851 which was about the science of physics written in laymen's terms.[1]

Pantelegraph

Pantèlègraph is a makeup word from "pantograph", a tool that copies words and drawings, plus "telegraph", an electromechanical system that sends messages through a wire over long distances. While Caselli was teaching physics at the University of Florence he devoted much of his research in the technology of telegraphic transmission of images as well as simple words.[1] Alexander Bain and Frederick Bakewell were also working on this technology.[3] The major problem of the time was to get perfect synchronization between the transmitting and receiving parts so they would work together correctly.[1] Caselli developed an electrochemical technology with a "synchronizing apparatus" (regulating clock) to make the sending and receiving mechanisms work together that was far superior to any technology Bain or Bakewell had.[1][5]

The technology is relatively simple. An image is made using non-conductive ink on a piece of tin foil. A stylus, that is in the electrical circuit of the tin foil, is then passed over the foil where it lightly touches it. The stylus passes with parallel scans slightly apart. Electricity conducts where there is no ink and does not where there is ink. This causes on and off circuits matching the image as it scans. The signals are then sent along a long distance telegraph line. The receiver at the other end has an electrical stylus and scans blue dye ink on white paper reproducing the image line-by-line, a fac simile (Latin, "make similar") of the original image.[10]

Caselli made a prototype of his system by 1856 and presented to Leopold II, Grand Duke of Tuscany, in a demonstration.[3] The Duke was so impressed with Caselli's device that for a while he financed his experiments.[1] When the Duke's enthusiasm waned Caselli moved to Paris to introduce his invention to Napoleon III.[3] Napoleon immediately became an enthusiastic admirer of the technology.[3] Between 1857 and 1861 Caselli developed out his pantelegraph (a.k.a. "autotelegraph") in Paris under the guidance of French inventor and mechanical engineer Léon Foucault.[1]

In 1858 Caselli's improved version was demonstrated by French physicist Alexandre-Edmond Becquerel at the Academie of Science in Paris.[11] Napoleon saw a demonstration of Caselli's pantelegraph in 1860 and placed an order for the service within the French national telegraph network that started the next year.[11] Caselli had access to not only the French telegraph lines for his pantelegraph facsimile machine technology, but finances were provided by Napoleon.[10] A test was done successfully then between Paris and Amiens with the signature of the composer Gioacchino Rossini as the image sent and received, a distance of 140 km.[11] A further test was done then between Paris and Marseille, a distance of 800 km, which was also successful.[11] French law was enacted then in 1864 for it to be officially accepted.[11] The next year in 1865 the operations started with the Paris to Lyon line and extended to Marseille in 1867.[12][13] Alexander Graham Bell did not receive his telephone patent (No. 174,465) by the U.S. Patent Office until 1876.[14]

-

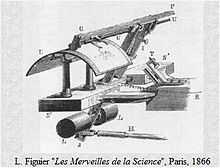

Caselli's pantelegraph patented in 1861

-

Pantelegraph "reading" tinfoil mechanism

-

Pantelegraph image, Paris to Lyons on 10 Feb 1862

-

Caselli pantelegraph images were blue ink

Later life

Caselli patented his pantèlègraphe in Europe in 1861 (E.P. 2532) and in the United States in 1863 (No. 37,563). Caselli demonstrated his pantelegraph successfully in 1861 at the Florence Exhibition to an audience which included King Victor Emmanuel, King of Italy.[3] Caselli's pantelegraph started out so successful that Napoleon awarded him the Legion of Honor.[15] Parisian scientists and engineers started the Pantelegraph Society to share ideas and concepts about the pantelegraph.[15]

The French Legislature and Council of State authorized a permanent line between Paris and Marseille. In England they authorized an experimental line between London and Liverpool for a four-month period. Napoleon bought Caselli's pantelegraph as a public service and put into place for the transmission of images from Paris to Lyon. It was in place until the defeat of Sedan in 1870. Russian Tsar Nicolas I put in an experimental service in place between his palaces in Saint Petersburg and Moscow between 1851 and 1855. In the first year of operation of the pantelegraph the system transmitted almost 5,000 faxes,[3] with a peak of faxes being sent at the rate of 110 per hour.[9] In spite of all this, the technology developed so slowly to make it fully reliable that it fell into oblivion.[15] Caselli ultimately gave up on his invention and returned to Florence where he died.[15] It was another 100 years before Caselli's technology became popular.[9]

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 Huurdeman, p. 149

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Istituto Tecnico Industriale, Rome, Italy. Italian biography of Giovanni Caselli

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 The Hebrew University of Jerusalem - Giovanni Caselli biography

- ↑ Giovanni Caselli This unique machine was a precursor of commonly known since the 1980s fax mashine.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Mid Nineteenth Century Electrochemistry

- ↑ Huurdeman, p. 149 The first telefax machine to be used in practical operation was invented by an Italian priest and professor of physics, Giovanni Caselli (1815 - 1891).

- ↑ Beyer, p. 100 The telegraph was the hot new technology of the moment, and Caselli wondered if it was possible to send pictures over telegraph wires. He went to work in 1855, and over the course of six years perfected what he called the "pantelegraph." It was the world's first practical fax machine.

- ↑ Giovanni Caselli

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Beyer, p. 100

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Schiffer, p. 203

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Huurdeman, p. 150

- ↑ Huurdeman, p. 150 This test was also successful, so that the pantelegraph became accepted for use on the French telegraph network by law on April 24, 1864. Official operation started on the Paris-Lyon line on February 16, 1865 and was extended to Marseille in 1867.

- ↑ Sarkar, p. 67 Italian physicist Giovanni Caselli built a machine to send and receive images over long distances using telegraph that he called pantelegraph. It was used by the French Post/Telegraph agency between Paris and Marseille from 1867 to 1870.

- ↑ Patent 174,465

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Cavendish, p. 280

Bibliography

- Beyer, Rick, The Greatest Stories Never Told : 100 tales from history to astonish, bewilder, & stupefy, A&E Television Networks, 2003, ISBN 0-06-001401-6

- Cavendish, Marshall (Corp), Inventors and Inventions, Marshall Cavendish, 2007, ISBN 0-7614-7763-2

- Huurdeman, Anton A., The worldwide history of telecommunications, Wiley-IEEE, 2003, ISBN 0-471-20505-2

- Sarkar, Tapan K. et al., History of wireless, John Wiley and Sons, 2006, ISBN 0-471-71814-9

- Schiffer, Michael B., Power Struggles: Scientific Authority and the Creation of Practical Electricity Before Edison, MIT Press, 2008, ISBN 0-262-19582-8

Pictures of pantelegraph

|