Giants (Greek mythology)

In Greek mythology, the Giants or Gigantes (Greek: Γίγαντες, Gigantes) were a race of great strength and aggression, though not necessarily of great size, known primarily for the Gigantomachy, their battle with the Olympian gods.[1] According to Hesiod, they were the children of Gaia (Earth) and her husband Uranus (Sky), born from the blood that fell upon Gaiia when Uranus was castrated by their son Cronus.[2]

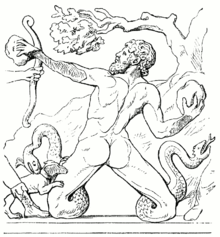

Archaic and Classical representations always show the Giants as man-sized hoplites wearing armor.[3] Later representations (with the first example from c. 380 BC) show Giants with snakes for legs.[4]

Gigantomachy

Gaia, incensed by the imprisonment of the Titans in Tartarus by the Olympians, incited the Giants to rise up in arms against them, end their reign, and restore the Titans' rule. Led on by Alcyoneus, Polybotes, Enceladus and Porphyrion, they tested the strength of the Olympians in what is known as the Gigantomachia or Gigantomachy. The Giants Otus and Ephialtes hoped to reach the top of Mount Olympus by stacking the mountain ranges of Thessaly, Pelion, and Ossa on top of each other.

The Olympians called upon the aid of Heracles after a prophecy warned them that he was required to defeat the Giants, for the aid of a mortal was needed.[5] Athena, instructed by Zeus, sought out Heracles and requested his participation in the battle. Heracles responded to Athena's request by shooting an arrow dipped in the poisonous blood of the dreaded Hydra at Alcyoneus, which made the Giant fall to the earth. However, the Giant was immortal so long as he remained in Pallene. Athena advised Heracles to drag Alcyoneus outside Pallene to make the Giant susceptible to death. Once outside Pallene, he was beaten to death by Heracles. Heracles slew not only Alcyoneus, but dealt the death blow to the Giants who had been wounded by the Olympians. The Giants who died by the hero's hands were Alcyoneus, Ephialtes, Leon, Peloreus, Porphyrion and Theodamas.[6]

The Olympians fought the Giants with the Moirai aiding them before the aforementioned prophecy was made, meaning the Giants would have overcome the combined efforts of both Olympus and the Sisters of Fate had Heracles not fought.

This battle occurred in the time when Heracles lived, so many events had already happened: the establishment of the Olympian gods, their progeny, the adventures of Perseus (forefather of Heracles) and so on. Thus in the Gigantomachy, the Moirai and Heracles, having joined the Olympians, defeated the Giants and quelled the rebellion, confirming their reign over the earth, sea, and heaven, and confining the Giants into Tartarus. The only Giant not slain in the conflict was Aristaios, who was turned into a dung beetle by Gaia so the Giant might be safe from the wrath of the Olympians.[7]

Whether the Gigantomachy was interpreted in ancient times as a kind of indirect "revenge of the Titans" upon the Olympians—as the Giants' reign would have been in some fashion a restoration of the age of the Titans—is not attested in any of the few literary references. Later Hellenistic poets and Latin ones tended to blur Titans and Giants.[8]

According to the Greeks, the Giants were buried by the gods beneath the earth, where their writhing caused volcanic activity and earthquakes.

In iconic representations the Gigantomachy was a favorite theme of the Greek vase-painters of the 5th century BC.

More impressive depictions of the Gigantomachy can be found in classical sculptural relief, such as the great altar of Pergamon, where the serpent-legged giants are locked in battle with a host of gods, or in the 5th century Temple of Olympian Zeus at Acragas.[9]

The names of the Giants

_-_20050429.jpg)

Some of the Giants identified by individual names were:

- Eurymedon: Mentioned by Homer[10] as a king of the Giants.

- Alcyoneus: One of the strongest of the Giants, along with Porphyrion. Slain by his own grandnephew, Heracles.

- Porphyrion: One of the strongest of the Giants, along with Alcyoneus. He is referred to by Pindar as king of the Giants.[11] Wounded by his nephew Zeus with lightning bolts and finished off with an arrow by his grandnephew Heracles.

- Agrios: Clubbed to death by his three nieces/grandnieces, the Moirai, with clubs of bronze.

- Clytius: Immolated by his niece Hecate with flaming torches.[12]

- Enceladus: Killed by his grandniece, Athena, and buried underneath Mount Etna, like Typhon, on Sicily.

- Ephialtes of the Aloadae: Shot by grandnephews Apollo and Heracles with arrows, or inadvertently killed by Otus.

- Eurytus: Slain by grandnephew Dionysus with his pine-cone tipped thyrsos.

- Gration: Slain by his grandniece, the goddess Artemis with her arrows.

- Hippolytus: Slain by his grandnephew Hermes with his sword and wearing the cap of invisibility.

- Leon: the lion headed giant slain by Heracles in the giants war

- Mimas: Slain by grandnephew Hephaestus with a volley of molten iron, or slain by Ares and robbed of his armor.[13]

- Otus of the Aloadae: Shot by grandnephews Apollo and Heracles with arrows, or inadvertently killed by Ephialtes.

- Pallas: Killed by grandniece Athena.

- Pelorus: Slain by the Olympian Ares.[14]

- Polybotes: Crushed by nephew Poseidon beneath the island of Nisyros.

- Thoon: Clubbed to death, like Agrios, by his three nieces/grandnieces, the Moirai, with clubs of bronze.

- Damasen: Saved the nymph Moria from a drakon

See also

Notes

- ↑ Hansen, pp. 177–179; Gantz, pp. 445–454.

- ↑ Hesiod, Theogony :185. Hyginus gives Tartarus as the father of the Giants. A parallel to the Giants' birth is the birth of Aphrodite from the similarly fertilized sea.

- ↑ Gantz, pp. 446, 447.

- ↑ Gantz, p. 453.

- ↑ Apollodorus, Library

- ↑ http://www.theoi.com/Gigante/Gigantes.html

- ↑ http://www.theoi.com/Gigante/Gigantes.html

- ↑ In a surviving fragment of Naevius' poem on the Punic war, he describes the Giants Runcus and Purpureus (Porphyrion): Eduard Fraenkel remarks of these lines, with their highly unusual plural Atlantes, "It does not surprise us to find the names Titani and Gigantes employed indiscriminately to denote the same mythological creatures, for we are used to the identification, or confusion, of these two types of monsters which, though not original, had probably become fairly common by the time of Naevius". (Fraenkel, "The Giants in the Poem of Naevius" The Journal of Roman Studies 44 (1954, pp. 14-17) p. 15 and note.

- ↑ A repertory of the theme in Greek arts is offered in Francis Vian, Répertoire des gigantomachie figurées (Paris) 1951 and his La Guerre des Géants (Paris) 1952.

- ↑ Odyssey 7.54 ff..

- ↑ Pindar, Pythian 8.

- ↑ Bibliotheca 1. 6. 2

- ↑ Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica III.1226–1227

- ↑ Claudian, Gigantomachy 73–82.

References

- Burkert, Walter (1991). Greek Religion. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0631156246.

- Gantz, Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0801853609 (Vol. 1)

- "Gigantes"— Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities

- Hansen, William, Handbook of Classical Mythology, ABC-CLIO, 2004. ISBN 978-1576072264.

- Hesiod, Theogony, in The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, Cambridge, MA.,Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914.

- Homer; The Odyssey with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, PH.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1919

- Smith, William; Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, London (1873). "Gigantes"

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gigantes. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||