Gerardus Mercator

| Gerardus Mercator | |

|---|---|

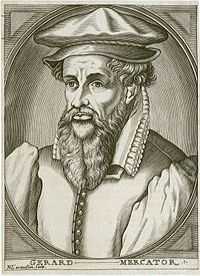

Portrait | |

| Born |

Gerard de Kremer March 5, 1512 Rupelmonde, County of Flanders (modern-day Belgium) |

| Died |

December 2, 1594 (aged 82) Duisburg, United Duchies of Jülich-Cleves-Berg (modern-day Germany) |

| Education | University of Leuven |

| Known for |

1569 World Map Mercator projection |

| Spouse(s) | Barbara Schellekens (1534-1586) |

| Children | Arnold (eldest), Emerentia, Dorothes, Bartholomeus, Rumold, Catharina |

Gerardus Mercator (born 5 March 1512 in Rupelmonde, County of Flanders (in modern Belgium), died 2 December 1594 in Duisburg, United Duchies of Jülich-Cleves-Berg, (modern-day Germany)) was a cartographer, philosopher and mathematician. He is best known for his work in cartography, in particular the world map of 1569 based on a new projection which represented sailing courses of constant bearing as straight lines. He was the first to use the term Atlas for a collection of maps.

Life and works

Mercator was born Gerard de Kremer or de Cremer in the town of Rupelmonde in the County of Flanders (modern-day Belgium) to parents from Gangelt in the Duchy of Jülich, where he was raised. "Mercator" is the Latinized form of his name. It means "merchant". He was educated in 's-Hertogenbosch by the famous humanist Macropedius and at the University of Leuven (both in the historical Duchy of Brabant). Despite Mercator's fame as a cartographer, his main source of income came through his craftsmanship of mathematical instruments. In Leuven, he worked with Gemma Frisius and Gaspar Van Der Heyden (Gaspar Myrica) from 1535 to 1536 to construct a terrestrial globe, although the role of Mercator in the project was not primarily as a cartographer, but rather as a highly skilled engraver of brass plates. Mercator's own independent map-making began only when he produced a map of Palestine in 1537; this map was followed by another—a map of the world (1538)[2] – and a map of the County of Flanders (1540). During this period he learned Italic script because it was the most suitable type of script for copper engraving of maps. He wrote the first instruction book of Italic script published in northern Europe.

Mercator was charged with heresy in 1544 on the basis of his sympathy for Protestant beliefs and suspicions about his frequent travels.[note 1] He was in prison for seven months before the charges were dropped—possibly because of intervention from the university authorities.[3]

In 1552, he moved to Duisburg, one of the major cities in the Duchy of Cleves, and opened a cartographic workshop where he completed a six-panel map of Europe in 1554. He worked also as a surveyor for the city. His motives for moving to Duisburg are not clear. Mercator might have left Flanders for religious reasons or because he was informed about the plans to found a university. He taught mathematics at the academic college of Duisburg. In 1564, after producing several maps, he was appointed Court Cosmographer to Wilhelm, Duke of Jülich-Cleves-Berg. In 1569 he devised a new projection for a nautical chart which had orthogonal lines of longitude, spaced evenly, and lines of latitude spaced so that sailing courses of constant bearing were represented as straight lines (loxodromes).

Mercator took the word atlas to describe a collection of maps, and encouraged Abraham Ortelius to compile the first modern world atlas – Theatrum Orbis Terrarum – in 1570. He produced his own atlas in a number of parts, the first of which was published in 1578 and consisted of corrected versions of the maps of Ptolemy (though introducing a number of new errors). Maps of France, Germany and the Netherlands were added in 1585 and of the Balkans and Greece in 1588; further maps were published by Mercator's son Rumold Mercator in 1595 after the death of his father.

Mercator learnt globe making from Gemma Frisius and went on to become the leading European globe maker of the age. Twenty-two pairs of his globes (terrestrial globe and matching celestial globe) have survived.

Following his move to Duisburg, Mercator never left the city and died there, a respected and wealthy citizen.

Legacy

Mercator is buried in Duisburg's main church of Saint Salvatorus. Exhibits of his works can be seen in the Mercator treasury located in the city.

More exhibits about Mercator's life and work are featured at the Mercator Museum in Sint-Niklaas, Belgium.

2012 marked the 500th anniversary of Mercator's birth. On 4 March 2012, celebrations of Mercator's life were held at his birthplace, Rupelmonde.

Notes

- ↑ The charges of Lutheran heresy laid against Mercator and forty others were deadly serious: two men were burnt at the stake, another was beheaded and two women were entombed alive.

References

See also

Further reading

- Nicholas Crane: Mercator: the man who mapped the planet, London: Phoenix, 2003, ISBN 0-7538-1692-X

- A. S. Osley, Mercator: A Monograph on the Lettering of Maps, etc. in the 16th Century Netherlands, with a facsimile and translation of his treatise on the italic hand and a translation of Ghim's Vita Mercatoris, London, Faber, 1969.

- Peter Osborne, The Mercator projections.

- Roger Calcoen et al, ed. (1994). Le cartographe Gerard Mercator 1512—1694. Bruxelles: Credit Communal. ISBN 2-87193-202-6.

External links

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Gerardus Mercator |

500 Years Mercator - Events

- Mercator revisited - Cartography in the Age of discovery, 25-28 April 2012, International conference in Sint-Niklaas, Belgium.

- 500 Years Gerhard Mercator - Early Cartography in the Habsburg Empire, and Commemoration of Mercator's 500th Birthday - 30. IMCoS Symposium, 9-12 September 2012, Vienna, Austria. IMCoS is the International Map Collectors' Society based in United Kingdom.

Other resources

- Turn the pages of the British Library's Mercator Atlas of Europe (c.1570)

- Mercator's Atlas

- India Tertia and the mapping of the colonial imaginary by Siddharth Varadarajan

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Gerardus Mercator", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- Mercator world map dating from 1538 at the American Geographical Society Library

|