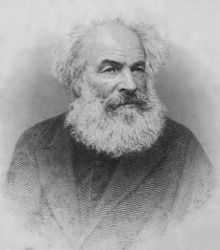

George Métivier

George Métivier (1790–1881) was a Guernsey poet dubbed the "Guernsey Burns", and sometimes considered the island's national poet. He wrote in Guernésiais, which is the indigenous language of the island. Among his poetical works are Rimes Guernesiaises published in 1831. Métivier blended together local place-names, bird and animal names, traditional sayings and orally transmitted fragments of medieval poetry to create these.

- Que l'lingo seit bouan ou mauvais / J'pâlron coum'nou pâlait autefais (whether the "lingo" be good or bad, I’m going to speak the way we spoke back then), wrote Métivier.

He was born in Rue de la Fontaine, St Peter Port, Guernsey, in the night of 28–29 January 1790.[1] He used the pen-name Un Câtelain, as his grandfather, a Huguenot by origin, had settled in Castel. As a young man, Métivier had studied in England and Scotland for a career in medicine, but had abandoned the idea of becoming a doctor to devote himself to linguistics and literature. His poems were published in Guernsey newspapers from 1813 until his death and since.

George Métivier corresponded publicly in verse form with Robert Pipon Marett ("Laelius"), the Jèrriais poet. He translated the Gospel according to Matthew into Guernésiais for publication by Prince Louis-Lucien Bonaparte, who visited him in 1862.[2] Métivier's close friend and protégé was Denys Corbet 1826-1909, born in Vale, Guernsey.

Influence

The first to produce a dictionary of the Norman language in the Channel Islands, Métivier's Dictionnaire Franco-Normand (1870), established the first standard orthography of Guernésiais - later modified and modernised.

At the end of the 18th century and beginning of the 19th century a new movement arose in the Channel Islands, led by writers such as Métivier and writers from Jersey. The independent governments, lack of censorship and diverse social and political milieu of the Islands enabled a growth in the publication of vernacular literature — often satirical and political.

Most literature was published in the large number of competing newspapers, which also circulated in the neighbouring Cotentin peninsula, sparking a literary renaissance on the Norman mainland.

La Victime

- Veis-tu l’s écllaers, os-tu l’tounère?

- Lé vent érage et la née a tché!

- Les douits saont g’laïs, la gnièt est nère -

- Ah, s’tu m’ôimes ouvre l’hus - ch’est mé!

- (Do you see the lightning, do you hear the thunder?

- The wind is raging and the snow has fallen!

- The brooks are frozen, the night is dark -

- Ah, if you love me open the door - it’s me!)

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to George Métivier. |

- ↑ La Grève de Lecq, Roger Jean Lebarbenchon, 1988 ISBN 2-905385-13-8 (French)

- ↑ La Gazette Officielle de Guernesey 13 September 1862

|