Geometric calculus

| Calculus |

|---|

|

Integral calculus

|

|

Specialized calculi |

In mathematics, geometric calculus extends the geometric algebra to include differentiation and integration. The formalism is powerful and can be shown to encompass other mathematical theories including differential geometry and differential forms.[1]

Differentiation

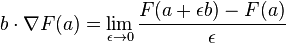

With a geometric algebra given, let a and b be vectors and let F(a) be a multivector-valued function. The directional derivative of F(a) along b is defined as

provided that the limit exists, where the limit is taken for scalar ε. This is similar to the usual definition of a directional derivative but extends it to functions that are not necessarily scalar-valued.

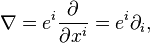

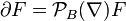

Next, choose a set of basis vectors  and let

and let  , where we use the Einstein summation notation. This allows the geometric derivative to be treated as an operator

, where we use the Einstein summation notation. This allows the geometric derivative to be treated as an operator

which is independent of the choice of frame. This is similar to the usual definition of the gradient, but it, too, extends to functions that are not necessarily scalar-valued.

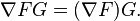

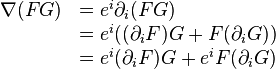

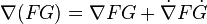

The standard order of operations for the geometric derivative is that it acts only on the function closest to its immediate right. Given two functions F and G, then for example we have

Product rule

Although the partial derivative exhibits a product rule, the geometric derivative only partially inherits this property. Consider two functions F and G:

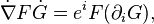

Since the geometric product is not commutative with  in general, we cannot proceed further without new notation. A solution is to adopt the overdot notation, in which the scope of a geometric derivative with an overdot is the multivector-valued function sharing the same overdot. In this case, if we define

in general, we cannot proceed further without new notation. A solution is to adopt the overdot notation, in which the scope of a geometric derivative with an overdot is the multivector-valued function sharing the same overdot. In this case, if we define

then the product rule for the geometric derivative is

Interior and exterior derivative

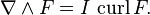

Let F be an r-grade multivector. Then we can define an additional pair of operators, the interior and exterior derivatives,

In particular, if F is grade 1 (vector-valued function), then we can write

and identify the divergence and curl as

Note, however, that these two operators are considerably weaker than the geometric derivative counterpart for several reasons. Neither the interior derivative operator nor the exterior derivative operator is invertible. Unlike the exterior product, the exterior derivative is not even associative.

Integration

Let  be a set of basis vectors that span an n-dimensional vector space. From geometric algebra, we interpret the pseudoscalar

be a set of basis vectors that span an n-dimensional vector space. From geometric algebra, we interpret the pseudoscalar  to be the signed volume of the n-parallelotope subtended by these basis vectors. If the basis vectors are orthonormal, then this is the unit pseudoscalar.

to be the signed volume of the n-parallelotope subtended by these basis vectors. If the basis vectors are orthonormal, then this is the unit pseudoscalar.

More generally, we may restrict ourselves to a subset of k of the basis vectors, where  , to treat the length, area, or other general k-volume of a subspace in the overall n-dimensional vector space. We denote these selected basis vectors by

, to treat the length, area, or other general k-volume of a subspace in the overall n-dimensional vector space. We denote these selected basis vectors by  . A general k-volume of the k-parallelotope subtended by these basis vectors is the grade k multivector

. A general k-volume of the k-parallelotope subtended by these basis vectors is the grade k multivector  .

.

Even more generally, we may consider a new set of vectors  proportional to the k basis vectors, where each of the

proportional to the k basis vectors, where each of the  is a component that scales one of the basis vectors. We are free to choose components as infinitesimally small as we wish as long as they remain nonzero. Since the outer product of these terms can be interpreted as a k-volume, a natural way to define a measure is

is a component that scales one of the basis vectors. We are free to choose components as infinitesimally small as we wish as long as they remain nonzero. Since the outer product of these terms can be interpreted as a k-volume, a natural way to define a measure is

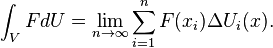

The measure is therefore always proportional to the unit pseudoscalar of a k-dimensional subspace of the vector space. Compare the Riemannian volume form in the theory of differential forms. The integral is taken with respect to this measure:

More formally, consider some directed volume V of the subspace. We may divide this volume into a sum of simplices. Let  be the coordinates of the vertices. At each vertex we assign a measure

be the coordinates of the vertices. At each vertex we assign a measure  as the average measure of the simplices sharing the vertex. Then the integral of F(x) with respect to U(x) over this volume is obtained in the limit of finer partitioning of the volume into smaller simplices:

as the average measure of the simplices sharing the vertex. Then the integral of F(x) with respect to U(x) over this volume is obtained in the limit of finer partitioning of the volume into smaller simplices:

Fundamental theorem of geometric calculus

The reason for defining the geometric derivative and integral as above is that they allow a strong generalization of Stokes' theorem. Let  be a multivector-valued function of r-grade input A and general position x, linear in its first argument. Then the fundamental theorem of geometric calculus relates the integral of a derivative over the volume V to the integral over its boundary:

be a multivector-valued function of r-grade input A and general position x, linear in its first argument. Then the fundamental theorem of geometric calculus relates the integral of a derivative over the volume V to the integral over its boundary:

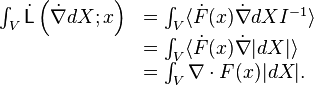

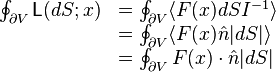

As an example, let  for a vector-valued function F(x) and a (n-1)-grade multivector A. We find that

for a vector-valued function F(x) and a (n-1)-grade multivector A. We find that

and likewise

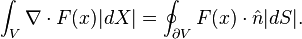

Thus we recover the divergence theorem,

Covariant derivative

A sufficiently smooth k-surface in an n-dimensional space is deemed a manifold. To each point on the manifold, we may attach a k-blade B that is tangent to the manifold. Locally, B acts as a pseudoscalar of the k-dimensional space. This blade defines a projection of vectors onto the manifold:

Just as the geometric derivative  is defined over the entire n-dimensional space, we may wish to define an intrinsic derivative

is defined over the entire n-dimensional space, we may wish to define an intrinsic derivative  , locally defined on the manifold:

, locally defined on the manifold:

(Note: The right hand side of the above may not lie in the tangent space to the manifold. Therefore it is not the same as  , which necessarily does lie in the tangent space.)

, which necessarily does lie in the tangent space.)

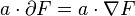

If a is a vector tangent to the manifold, then indeed both the geometric derivative and intrinsic derivative give the same directional derivative:

Although this operation is perfectly valid, it is not always useful because  itself is not necessarily on the manifold. Therefore we define the covariant derivative to be the forced projection of the intrinsic derivative back onto the manifold:

itself is not necessarily on the manifold. Therefore we define the covariant derivative to be the forced projection of the intrinsic derivative back onto the manifold:

Since any general multivector can be expressed as a sum of a projection and a rejection, in this case

we introduce a new function, the shape tensor  , which satisfies

, which satisfies

where  is the commutator product. In a local coordinate basis

is the commutator product. In a local coordinate basis  spanning the tangent surface, the shape tensor is given by

spanning the tangent surface, the shape tensor is given by

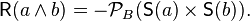

Importantly, on a general manifold, the covariant derivative does not commute. In particular, the commutator is related to the shape tensor by

Clearly the term  is of interest. However it, like the intrinsic derivative, is not necessarily on the manifold. Therefore we can define the Riemann tensor to be the projection back onto the manifold:

is of interest. However it, like the intrinsic derivative, is not necessarily on the manifold. Therefore we can define the Riemann tensor to be the projection back onto the manifold:

Lastly, if F is of grade r, then we can define interior and exterior covariant derivatives as

and likewise for the intrinsic derivative.

Relation to differential geometry

On a manifold, locally we may assign a tangent surface spanned by a set of basis vectors  . We can associate the components of a metric tensor, the Christoffel symbols, and the Riemann tensor as follows:

. We can associate the components of a metric tensor, the Christoffel symbols, and the Riemann tensor as follows:

These relations embed the theory of differential geometry within geometric calculus.

Relation to differential forms

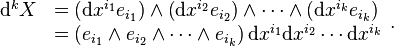

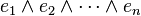

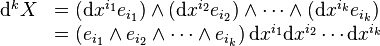

In a local coordinate system (x1, ..., xn), the coordinate differentials dx1, ..., dxn form a basic set of one-forms within the coordinate chart. Given a multi-index i1, ..., ik with 1 ≤ ip ≤ n for 1 ≤ p ≤ k, we can define a k-form

We can alternatively introduce a k-grade multivector A as

and a measure

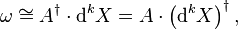

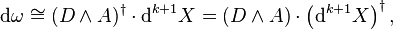

Apart from a subtle difference in meaning for the exterior product with respect to differential forms versus the exterior product with respect to vectors (indeed one should note that in the former the increments are covectors, whereas in the latter they represent scalars), we see the correspondences of the differential form

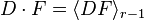

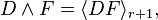

its derivative

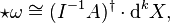

and its Hodge dual

embed the theory of differential forms within geometric calculus.

History

Following is a diagram summarizing the history of geometric calculus.

References

- ↑ David Hestenes, Garrett Sobczyk: Clifford Algebra to Geometric Calculus, a Unified Language for mathematics and Physics (Dordrecht/Boston:G.Reidel Publ.Co., 1984, ISBN 90-277-2561-6

![[a\cdot D,\,b\cdot D]F=-({\mathsf {S}}(a)\times {\mathsf {S}}(b))\times F.](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/1/e/4/3/1e436b5356721bf64c8ecd18d3910682.png)