Geography of Brazil

| Geography of Brazil | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location of Brazil | |

| Surface Area of Brazil | |

| Total | 8,514,877 km2 (3,287,612 sq mi) |

| Land | 8,459,417 km2 (3,266,199 sq mi) |

| Water | 55,460 km2 (21,410 sq mi) |

| Notes:[1][2] | |

| Boundaries | |

| Coastline | 7,491 km (4,655 mi) |

| Total land boundary | 16,885 km (10,492 mi) |

| Border countries | |

| Territories and claims | |

| |

| Brazilian territories and claims | |

| Islands |

|

| Informal claim | Brazilian Antarctica |

| Maritime claims | |

| Contiguous zone | 24 nmi (44.4 km; 27.6 mi) |

| Continental shelf | 200 nmi (370.4 km; 230.2 mi) |

| Exclusive Economic Zone | 200 nmi (370.4 km; 230.2 mi) |

| Territorial sea | 12 nmi (22.2 km; 13.8 mi) |

| Land use | |

| Arable land | 6.93% (2005) |

| Permanent crop | 0.89% (2005) |

| Other | 92.18% (2005) |

| Irrigated land | 29,200 km2 (11,300 sq mi) (2003) |

The country of Brazil occupies roughly half of South America, bordering the Atlantic Ocean. Brazil covers a total area of 8,514,215 km2 (3,287,357 sq mi) which includes 8,456,510 km2 (3,265,080 sq mi) of land and 55,455 km2 (21,411 sq mi) of water. The highest point in Brazil is Pico da Neblina at 2,994 m (9,823 ft). Brazil is bordered by the countries of Argentina, Bolivia, Colombia, French Guiana, Guyana, Paraguay, Peru, Suriname, Uruguay and Venezuela.

Much of the climate is tropical, with the south being relatively temperate. The largest river in Brazil, and one of the longest in the world, is the Amazon. The rainforest that covers the Amazon Basin constitutes almost half of the rainforests on Earth.

Geographic coordinates: 10°S 55°W / 10°S 55°WCoordinates: 10°S 55°W / 10°S 55°W

Size and location

With its expansive territory, Brazil occupies most of the eastern part of the South American continent and its geographic heartland, as well as various islands in the Atlantic Ocean. The only countries in the world that are larger are Russia, Canada, the People's Republic of China, and the United States. The national territory extends 4,395 kilometers (2,731 mi) from north to south (5°16'20" N to 33°44'32" S latitude), making Brazil the longest country in the world and 4,319 kilometers (2,684 mi) from east to west (34°47'30" W to 73°59'32" W longitude). It spans three time zones, the easternmost of which is one hour ahead of Eastern Standard Time in the United States. The time zone of the capital (Brasília) and of the most populated part of Brazil along the east coast (UTC-3) is two hours ahead of Eastern Standard Time, except when it is on its own daylight saving time, from October to February. The Atlantic islands are in the easternmost time zone.

Brazil possesses the archipelago of Fernando de Noronha, located 350 kilometers (217 mi) northeast of its "horn", and several small islands and atolls in the Atlantic - Abrolhos, Atol das Rocas, Penedos de São Pedro e São Paulo, Trindade, and Martim Vaz. In the early 1970s, Brazil claimed a territorial sea extending 362 kilometers (225 mi) from the country's shores, including those of the islands.

On Brazil's east coast, the Atlantic coastline extends 7,367 kilometers (4,578 mi). In the west, in clockwise order from the south, Brazil has 15,719 kilometers (9,767 mi) of borders with Uruguay, Argentina, Paraguay, Bolivia, Peru, Colombia, Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname, and French Guiana. The only South American countries with which Brazil does not share borders are Chile and Ecuador. A few short sections are in question, but there are no true major boundary controversies with any of the neighboring countries.

Brazil has six major ecosystems: the Amazon Basin, a tropical rainforest system; the Pantanal bordering Paraguay and Bolivia, a tropical wetland system; the Cerrado, a savanna system that covers much of the center of the country; the Caatinga or thorny scrubland habitat of the Northeast; the Atlantic Forest (Mata Atlântica) that extends along the entire coast from the Northeast to the South; and the Pampas or fertile lowland plains of the far South.

Geology, geomorphology and drainage

In contrast to the Andes, which rose to elevations of nearly 7,000 meters (22,966 ft) in a relatively recent epoch and inverted the Amazon's direction of flow from westward to eastward, Brazil's geological formation is very old. Precambrian crystalline shields cover 36% of the territory, especially its central area. The dramatic granite sugarloaf mountains in the city of Rio de Janeiro are an example of the terrain of the Brazilian shield regions, where continental basement rock has been sculpted into towering domes and columns by tens of millions of years of erosion, untouched by mountain-building events.

The principal mountain ranges average elevations just under 2,000 meters (6,562 ft). The Serra do Mar Range hugs the Atlantic coast, and the Serra do Espinhaço Range, the largest in area, extends through the south-central part of the country. The highest mountains are in the Tumucumaque, Pacaraima, and Imeri ranges, among others, which traverse the northern border with the Guianas and Venezuela.

In addition to mountain ranges (about 0.5% of the country is above 1,200 m or 3,937 ft), Brazil's Central Highlands include a vast central plateau (Planalto Central). The plateau's uneven terrain has an average elevation of 1,000 meters (3,281 ft). The rest of the territory is made up primarily of sedimentary basins, the largest of which is drained by the Amazon and its tributaries. Of the total territory, 41% averages less than 200 meters (656 ft) in elevation. The coastal zone is noted for thousands of kilometers of tropical beaches interspersed with mangroves, lagoons, and dunes, as well as numerous coral reefs.

Brazil has one of the world's most extensive river systems, with eight major drainage basins, all of which drain into the Atlantic Ocean. Two of these basins—the Amazon and Tocantins-Araguaia account for more than half the total drainage area. The largest river system in Brazil is the Amazon, which originates in the Andes and receives tributaries from a basin that covers 45.7% of the country, principally the north and west. The main Amazon river system is the Amazonas-Solimões-Ucayali axis (the 6,762-kilometer (4,202 mi)-long Ucayali is a Peruvian tributary), flowing from west to east. Through the Amazon Basin flows one-fifth of the world's fresh water. A total of 3,615 kilometers (2,246 mi) of the Amazon are in Brazilian territory. Over this distance, the waters decline only about 100 meters (330 ft). The major tributaries on the southern side are, from west to east, the Javari, Juruá, Purus (all three of which flow into the western section of the Amazon called the Solimões), Madeira, Tapajós, Xingu, and Tocantins. On the northern side, the largest tributaries are the Branco, Japurá, Jari, and Rio Negro. The above-mentioned tributaries carry more water than the Mississippi (its discharge is less than one-tenth that of the Amazon). The Amazon and some of its tributaries, called "white" rivers, bear rich sediments and hydrobiological elements. The black-white and clear rivers—such as the Negro, Tapajós, and Xingu—have clear (greenish) or dark water with few nutrients and little sediment.

The major river system in the Northeast is the Rio São Francisco, which flows 1,609 kilometers (1,000 mi) northeast from the south-central region. Its basin covers 7.6% of the national territory. Only 277 kilometers (172 mi) of the lower river are navigable for oceangoing ships. The Paraná system covers 14.5% of the country. The Paraná flows south among the Río de la Plata Basin, reaching the Atlantic between Argentina and Uruguay. The headwaters of the Paraguai, the Paraná's major eastern tributary, constitute the Pantanal, the largest contiguous wetlands in the world, covering as much as 230,000 square kilometers (89,000 sq mi).

Below their descent from the highlands, many of the tributaries of the Amazon are navigable. Upstream, they generally have rapids or waterfalls, and boats and barges also must face sandbars, trees, and other obstacles. Nevertheless, the Amazon is navigable by oceangoing vessels as far as 3,885 kilometers (2,414 mi) upstream, reaching Iquitos in Peru. The Amazon river system was the principal means of access until new roads became more important. Hydroelectric projects are Itaipu, in Paraná, with 12,600 MW; Tucuruí, in Pará, with 7,746 MW; and Paulo Afonso, in Bahia, with 3,986 MW.

Natural resources

Natural resources include: bauxite, gold, iron ore, manganese, nickel, phosphates, platinum, tin, Clay, uranium, petroleum, hydropower and timber.

Rivers and lakes

According to organs of the Brazilian government there are 12 major hydrographic regions in Brazil. Seven of these are river basins named after their main rivers; the other five are groupings of various river basins in areas which have no dominant river.

- 7 Hydrographic Regions named after their dominant rivers:

- 5 coastal Hydrographic Regions based on regional groupings of minor river basins (listed from north to south):

- Atlântico Nordeste Ocidental (Western North-east Atlantic)

- Atlântico Nordeste Oriental (Eastern North-east Atlantic)

- Atlântico Leste (Eastern Atlantic)

- Atlântico Sudeste (South-east Atlantic)

- Atlântico Sul (South Atlantic)

The Amazon River is the widest and second longest river (behind the Nile) in the world. This huge river drains the greater part of the world's rainforests. Another major river, the Paraná, has its source in Brazil. It forms the border of Paraguay and Argentina, then winds its way through Argentina and into the Atlantic Ocean, along the southern coast of Uruguay. The HBV hydrology transport model has been used to analyze certain pollutant transport in Brazil's river systems. The Amazon is full of eroded soil.

Soils and vegetation

Brazil's tropical soils produce 70 million tons of grain crops per year, but this output is attributed more to their extension than their fertility. Despite the earliest Portuguese explorers' reports that the land was exceptionally fertile and that anything planted grew well, the record in terms of sustained agricultural productivity has been generally disappointing. High initial fertility after clearing and burning usually is depleted rapidly, and acidity and aluminum content are often high. Together with the rapid growth of weeds and pests in cultivated areas, as a result of high temperatures and humidity, this loss of fertility explains the westward movement of the agricultural frontier and slash-and-burn agriculture; it takes less investment in work or money to clear new land than to continue cultivating the same land. Burning also is used traditionally to remove tall, dry, and nutrient-poor grass from pasture at the end of the dry season. Until mechanization and the use of chemical and genetic inputs increased during the agricultural intensification period of the 1970s and 1980s, coffee planting and farming in general moved constantly onward to new lands in the west and north. This pattern of horizontal or extensive expansion maintained low levels of technology and productivity and placed emphasis on quantity rather than quality of agricultural production.

The largest areas of fertile soils, called terra roxa (red earth), are found in the states of Paraná and São Paulo. The least fertile areas are in the Amazon, where the dense rain forest is. Soils in the Northeast are often fertile, but they lack water, unless they are irrigated artificially.

In the 1980s, investments made possible the use of irrigation, especially in the Northeast Region and in Rio Grande do Sul State, which had shifted from grazing to soy and rice production in the 1970s. Savanna soils also were made usable for soybean farming through acidity correction, fertilization, plant breeding, and in some cases spray irrigation. As agriculture underwent modernization in the 1970s and 1980s, soil fertility became less important for agricultural production than factors related to capital investment, such as infrastructure, mechanization, use of chemical inputs, breeding, and proximity to markets. Consequently, the vigor of frontier expansion weakened.

The variety of climates, soils, and drainage conditions in Brazil is reflected in the range of its vegetation types. The Amazon Basin and the areas of heavy rainfall along the Atlantic coast have tropical rain forest composed of broadleaf evergreen trees. The rain forest may contain as many as 3,000 species of flora and fauna within a 2.6-square-kilometer (1 sq mi) area. The Atlantic Forest is reputed to have even greater biological diversity than the Amazon rain forest, which, despite apparent homogeneity, contains many types of vegetation, from high canopy forest to bamboo groves.

In the semiarid Northeast, caatinga, a dry, thick, thorny vegetation, predominates. Most of central Brazil is covered with a woodland savanna, known as the cerrado (sparse scrub trees and drought-resistant grasses), which became an area of agricultural development after the mid-1970s. In the South (Sul), needle-leaved pinewoods (Paraná pine or araucaria) cover the highlands; grassland similar to the Argentine pampa covers the sea-level plains. The Mato Grosso swamplands (Pantanal Mato-grossense) is a Florida-sized plain in the western portion of the Center-West (Centro-Oeste). It is covered with tall grasses, bushes, and widely dispersed trees similar to those of the cerrado and is partly submerged during the rainy season.

Brazil, which is named after reddish dyewood (pau brasil), has long been famous for the wealth of its tropical forests. These are not, however, as important to world markets as those of Asia and Africa, which started to reach depletion only in the 1980s. By 1996 more than 90% of the original Atlantic forest had been cleared, primarily for agriculture, with little use made of the wood, except for araucaria pine in Paraná.

The inverse situation existed with regard to clearing for wood in the Amazon rain forest, of which about 15% had been cleared by 1994, and part of the remainder had been disturbed by selective logging. Because the Amazon forest is highly heterogeneous, with hundreds of woody species per hectare, there is considerable distance between individual trees of economic value, such as mahogany and cerejeira. Therefore, this type of forest is not normally cleared for timber extraction but logged through high-grading, or selection of the most valuable trees. Because of vines, felling, and transportation, their removal causes destruction of many other trees, and the litter and new growth create a risk of forest fires, which are otherwise rare in rain forests. In favorable locations, such as Paragominas, in the northeastern part of Pará State, a new pattern of timber extraction has emerged: diversification and the production of plywood have led to the economic use of more than 100 tree species.

Starting in the late 1980s, rapid deforestation and extensive burning in Brazil received considerable international and national attention. Satellite images have helped document and quantify deforestation as well as fires, but their use also has generated considerable controversy because of problems of defining original vegetation, cloud cover, and dealing with secondary growth and because fires, as mentioned above, may occur in old pasture rather than signifying new clearing. Public policies intended to promote sustainable management of timber extraction, as well as sustainable use of nontimber forest products (such as rubber, Brazil nuts, fruits, seeds, oils, and vines), were being discussed intensely in the mid-1990s. However, implementing the principles of sustainable development, without irreversible damage to the environment, proved to be more challenging than establishing international agreements about them.

Climate

Although 90% of the country is within the tropical zone, the climate of Brazil varies considerably from the mostly tropical North (the equator traverses the mouth of the Amazon) to temperate zones below the Tropic of Capricorn (23°27' S latitude), which crosses the country at the latitude of the city of São Paulo. Brazil has five climatic regions: equatorial, tropical, semiarid, highland tropical, and subtropical.

Temperatures along the equator are high, averaging above 25 °C (77 °F), but not reaching the summer extremes of up to 40 °C (104 °F) in the temperate zones. There is little seasonal variation near the equator, although at times it can get cool enough for wearing a jacket, especially in the rain. At the country's other extreme, there are frosts south of the Tropic of Capricorn during the winter (June–August), and there is snow in the mountainous areas, such as Paraná, Rio Grande do Sul and Santa Catarina. Temperatures in the cities of São Paulo, Belo Horizonte, and Brasília are moderate (usually between 15 and 30 °C or 59 and 86 °F), despite their relatively low latitude, because of their elevation of approximately 1,000 meters (3,281 ft). Rio de Janeiro, Recife, and Salvador on the coast have warm climates, with average temperatures ranging from 23 to 27 °C (73.4 to 80.6 °F), but enjoy constant trade winds. The southern cities of Porto Alegre and Curitiba have a subtropical climate similar to that in parts of the United States and Europe, and temperatures can fall below freezing in winter.

Precipitation levels vary widely. Most of Brazil has moderate rainfall of between 1,000 and 1,500 millimetres (39.4 and 59.1 in) a year, with most of the rain falling in the summer (between December and April) south of the Equator. The Amazon region is notoriously humid, with rainfall generally more than 2,000 millimetres (78.7 in) per year and reaching as high as 3,000 millimetres (118.1 in) in parts of the western Amazon and near Belém. It is less widely known that, despite high annual precipitation, the Amazon rain forest has a three- to five-month dry season, the timing of which varies according to location north or south of the equator.

High and relatively regular levels of precipitation in the Amazon contrast sharply with the dryness of the semiarid Northeast, where rainfall is scarce and there are severe droughts in cycles averaging seven years. The Northeast is the driest part of the country. The region also constitutes the hottest part of Brazil, where during the dry season between May and November, temperatures of more than 38 °C (100 °F) have been recorded. However, the sertão, a region of semidesert vegetation used primarily for low-density ranching, turns green when there is rain. Most of the Center-West has 1,500 to 2,000 millimetres (59.1 to 78.7 in) of rain per year, with a pronounced dry season in the middle of the year, while the South and most of the year without a distinct dry season.

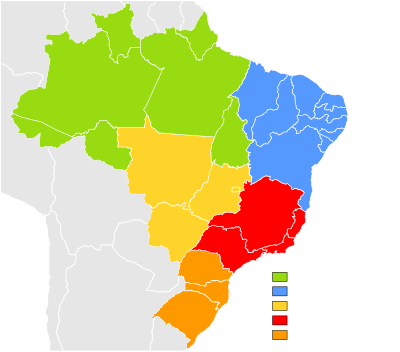

Geographic regions

Brazil's 26 states and the Federal District (Distrito Federal) are divided conventionally into five regions: North (Norte), Northeast (Nordeste), Southeast (Sudeste), South (Sul), and Center-West (Centro-Oeste) - see fig. 4. In 1996 there were 5,581 municipalities (municípios), which have municipal governments. Many municipalities, which are comparable to United States counties, are in turn divided into districts (distritos), which do not have political or administrative autonomy. In 1995 there were 9,274 districts. All municipal and district seats, regardless of size, are considered officially to be urban. For purely statistical purposes, the municipalities were grouped in 1990 into 559 micro-regions, which in turn constituted 136 meso-regions. This grouping modified the previous micro-regional division established in 1968, a division that was used to present census data for 1970, 1975, 1980, and 1985.

Each of the five major regions has a distinct ecosystem. Administrative boundaries do not necessarily coincide with ecological boundaries, however. In addition to differences in physical environment, patterns of economic activity and population settlement vary widely among the regions. The principal ecological characteristics of each of the five major regions, as well as their principal socioeconomic and demographic features, are summarized below.

Centerwest

The Center-West consists of the states of Goiás, Mato Grosso, Mato Grosso do Sul (separated from Mato Grosso in 1979) and the Federal District, where Brasília is located, the national capital. Until 1988 Goiás State included the area that then became the state of Tocantins in the North.

The Center-West has 1,612,077 square kilometers (622,426 sq mi) and covers 18.9% of the national territory. Its main biome is the cerrado, the tropical savanna in which natural grassland is partly covered with twisted shrubs and small trees. The cerrado was used for low-density cattle-raising in the past but is now also used for soybean production. There are gallery forests along the rivers and streams and some larger areas of forest, most of which have been cleared for farming and livestock. In the north, the cerrado blends into tropical forest. It also includes the Pantanal wetlands in the west, known for their wildlife, especially aquatic birds and caimans. In the early 1980s, 33.6% of the region had been altered by anthropic activities, with a low of 9.3% in Mato Grosso and a high of 72.9% in Goiás (not including Tocantins). In 1996 the Center-West region had 10.2 million inhabitants, or 6% of Brazil's total population. The average density is low, with concentrations in and around the cities of Brasília, Goiânia, Campo Grande, and Cuiabá. Living standards are below the national average. In 1994 they were highest in the Federal District, with per capita income of US$7,089 (the highest in the nation), and lowest in Mato Grosso, with US$2,268.

Northeast

The nine states that make up the Northeast are Alagoas, Bahia, Ceará, Maranhão, Paraíba, Pernambuco, Piauí, Rio Grande do Norte, and Sergipe. The Fernando de Noronha archipelago (formerly the federal territory of Fernando de Noronha, now part of Pernambuco state) is also included in the Northeast.

The Northeast, with 1,561,178 square kilometers (602,774 sq mi), covers 18.3% of the national terrest concentration of rural population, and its living standards are the lowest in Brazil. In 1994 Piauí had the lowest per capita income in the region and the country, only US$835, while Sergipe had the highest average income in the region, with US$1,958.

North

The equatorial North, also known as the Amazon or Amazônia, includes, from west to east, the states of Rondônia, Acre, Amazonas, Roraima, Pará, Amapá, and, as of 1988, Tocantins (created from the northern part of Goiás State, which is situated in the Center-West). Rondônia, previously a federal territory, became a state in 1986. The former federal territories of Roraima and Amapá were raised to statehood in 1988.

With 3,869,638 square kilometers (1,494,076 sq mi), the North is the country's largest region, covering 45.3% of the national territory. The region's principal biome is the humid tropical forest, also known as the rain forest, home to some of the planet's richest biological diversity. The North has served as a source of forest products ranging from "backlands drugs" (such as sarsaparilla, cocoa, cinnamon, and turtle butter) in the colonial period to rubber and Brazil nuts in more recent times. In the mid-twentieth century, nonforest products from mining, farming, and livestock-raising became more important, and in the 1980s the lumber industry boomed. In 1990, 6.6% of the region's territory was considered altered by anthropic (man-made) action, with state levels varying from 0.9% in Amapá to 14.0% in Rondônia.

In 1996 the North had 11.1 million inhabitants, only 7% of the national total. However, its share of Brazil's total had grown rapidly in the 1970s and early 1980s as a result of interregional migration, as well as high rates of natural increase. The largest population concentrations are in eastern Pará State and in Rondônia. The major cities are Belém and Santarém in Pará, and Manaus in Amazonas. Living standards are below the national average. The highest per capita income, US$2,888, in the region in 1994, was in Amazonas, while the lowest, US$901, was in Tocantins.

Southeast

The Southeast consists of the four states of Espírito Santo, Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro, and São Paulo. Its total area of 927,286 square kilometers (358,027 sq mi) corresponds to 10.9% of the national territory. The region has the largest share of the country's population, 63 million in 1991, or 39% of the national total, primarily as a result of internal migration since the mid-19th century until the 1980s. In addition to a dense urban network, it contains the megacities of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, which in 1991 had 18.7 million and 11.7 million inhabitants in their metropolitan areas, respectively. The region combines the highest living standards in Brazil with pockets of urban poverty. In 1994 São Paulo boasted an average income of US$4,666, while Minas Gerais reported only US$2,833.

Originally, the principal biome in the Southeast was the Atlantic Forest, but by 1990 less than 10% of the original forest cover remained as a result of clearing for farming, ranching, and charcoal making. Anthropic activity had altered 79.7% of the region, ranging from 75% in Minas Gerais to 91.1% in Espírito Santo. The region has most of Brazil's industrial production. The state of São Paulo alone accounts for half of the country's industries. Agriculture, also very strong, has diversified and now uses modern technology.

South

The three states in the temperate South: Paraná, Rio Grande do Sul, and Santa Catarina—cover 577,214 square kilometers (222,864 sq mi), or 6.8% of the national territory. The population of the South in 1991 was 23.1 million, or 14% of the country's total. The region is almost as densely settled as the Southeast, but the population is more concentrated along the coast. The major cities are Curitiba and Porto Alegre. The inhabitants of the South enjoy relatively high living standards. Because of its industry and agriculture, Paraná had the highest average income in 1994, US$3,674, while Santa Catarina, a land of small farmers and small industries, had slightly less, US$3,405.

In addition to the Atlantic Forest and Araucaria moist forests, much of which were cleared in the post-World War II period, the southernmost portion of Brazil contains the Uruguayan savanna, which extends into Argentina and Uruguay. In 1982, 83.5% of the region had been altered by anthropic activity, with the highest level (89.7%) in Rio Grande do Sul, and the lowest (66.7%) in Santa Catarina. Agriculture—much of which, such as rice production, is carried out by small farmers—has high levels of productivity. There are also some important industries.

Environmental issues

The environmental problem that attracted most international attention in Brazil in the 1980s was undoubtedly deforestation in the Amazon. Of all Latin American countries, Brazil still has the largest portion (66%) of its territory covered by forests, but clearing and burning in the Amazon proceeded at alarming rates in the 1970s and 1980s. Most of the clearing resulted from the activities of ranchers, including large corporate operations, and a smaller portion resulted from slash and burn techniques used by small farmers. Technical changes involved in the transition from horizontal expansion of agriculture to increasing productivity also accounted for decreasing rates of deforestation.

Desertification, another important environmental problem in Brazil, only received international attention following the United Nations Conference on the Environment and Development, also known as the Earth Summit, held in Rio de Janeiro in June 1992. Desertification means that the soils and vegetation of drylands are severely degraded, not necessarily that land turns into desert. In the early 1990s, it became evident that the semiarid caatinga ecosystem of the Northeast was losing its natural vegetation through clearing and that the zone was therefore running the risk of becoming even more arid, as was occurring also in some other regions.

In areas where agriculture is more intense and developed, there are serious problems of soil erosion, siltation and sedimentation of streams and rivers, and pollution with pesticides. In parts of the savannas, where irrigated soybean production expanded in the 1980s, the water table has been affected. Expansion of pastures for cattle raising has reduced natural biodiversity in the savannas. Swine effluents constitute a serious environmental problem in Santa Catarina in the South.

In urban areas, at least in the largest cities, levels of air pollution and congestion are typical of, or worse than, those found in cities in developed countries. At the same time, however, basic environmental problems related to the lack of sanitation, which developed countries solved long ago, persist in Brazil. These problems are sometimes worse in middle-sized and small cities than in large cities, which have more resources to deal with them. Environmental problems of cities and towns finally began to receive greater attention by society and the government in the 1990s.

According to many critics, the economic crisis in the 1980s worsened environmental degradation in Brazil because it led to overexploitation of natural resources, stimulated settlement in fragile lands in both rural and urban areas, and weakened environmental protection. At the same time, however, the lower level of economic activity may have reduced pressure on the environment, such as the aforementioned decreased level of investment in large-scale clearing in the Amazon. That pressure could increase if economic growth accelerates, especially if consumption patterns remain unchanged and more sustainable forms of production are not found.

In Brazil public policies regarding the environment are generally advanced, although their implementation and the enforcement of environmental laws have been far from ideal. Laws regarding forests, water, and wildlife have been in effect since the 1930s. Brazil achieved significant institutional advances in environmental policy design and implementation after the Stockholm Conference on the Environment in 1972. Specialized environmental agencies were organized at the federal level and in some states, and many national parks and reserves were established. By 1992 Brazil had established 34 national parks and fifty-six biological reserves. In 1981 the National Environment Policy was defined, and the National System for the Environment (Sistema Nacional do Meio Ambiente--Sisnama) was created, with the National Environmental Council (Conselho Nacional do Meio Ambiente--Conama) at its apex, municipal councils at its base, and state-level councils in between. In addition to government authorities, all of these councils include representatives of civil society.

The 1988 constitution incorporates environmental precepts that are advanced compared with those of most other countries. At that time, the Chamber of Deputies (Câmara dos Deputados) established its permanent Commission for Defense of the Consumer, the Environment, and Minorities. In 1989 the creation of the Brazilian Institute for the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renováveis--Ibama) joined together the federal environment secretariat and the federal agencies specializing in forestry, rubber, and fisheries. In 1990 the administration of Fernando Collor de Mello (president, 1990–92) appointed the well-known environmentalist José Lutzemberger as secretary of the environment and took firm positions on the environment and on Indian lands. In 1992 Brazil played a key role at the Earth Summit, not only as its host but also as negotiator on sustainable development agreements, including the conventions on climate and biodiversity. The Ministry of Environment was created in late 1992, after President Collor had left office. In August 1993, it became the Ministry of Environment and the Legal Amazon and took a more pragmatic approach than had the combative Lutzemberger. However, because of turnover in its leadership, a poorly defined mandate, and lack of funds, its role and impact were limited. In 1995 its mandate and name were expanded to include water resources—the Ministry of Environment, Hydraulic Resources, and the Legal Amazon—it began a process of restructuring to meet its mandate of "shared management of the sustainable use of natural resources." In 1997 the Commission on Policies for Sustainable Development and Agenda 21 began to function under the aegis of the Civil Household. One of its main tasks was to prepare Agenda 21 (a plan for the twenty-first century) for Brazil and to stimulate preparation of state and local agendas.

Institutional development at the official level was accompanied and in part stimulated by the growth, wide diffusion, and growing professional development of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) dedicated to environmental and socio-environmental causes. The hundreds of NGOs throughout Brazil produce documents containing both useful information and passionate criticisms. Among the Brazilian environmental NGOs, the most visible are SOS Atlantic Forest (SOS Mata Atlântica), the Social-Environmental Institute (Instituto Sócio-Ambiental—ISA), the Pro-Nature Foundation (Fundação Pró-Natureza—Funatura), and the Amazon Working Group (Grupo de Trabalho Amazônico—GTA). The Brazilian Forum of NGOs and Social Movements for the Environment and Development and the Brazilian Association of Nongovernmental Organizations (Associacão Brasileira de Organizações Não-Governamentais—ABONG) are national networks, and there are various regional and thematic networks as well. The main international environmental NGOs that have offices or affiliates in Brazil are the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), Conservation International (CI), and Nature Conservancy.

Especially after the events of the late 1980s, international organizations and developed countries have allocated significant resources for the environmental sector in Brazil. In 1992 environmental projects worth about US$6.8 million were identified, with US$2.6 in counterpart funds (funds provided by the Brazilian government). More than 70% of the total value was for sanitation, urban pollution control, and other urban environmental projects. Thus, the allocation of resources did not accord with the common belief that funding was influenced unduly by alarmist views on deforestation in the Amazon.

Among the specific environmental projects with international support, the most important was the National Environmental Plan (Plano Nacional do Meio Ambiente—PNMA), which received a US$117 million loan from the World Bank. The National Environmental Fund (Fundo Nacional do Meio Ambiente—FNMA), in addition to budgetary funds, received US$20 million from the Inter-American Development Bank to finance the environmental activities of NGOs and small municipal governments. The Pilot Program for the Conservation of the Brazilian Rain Forests (Programa Piloto para a Proteção das Florestas Tropicais do Brasil—PPG-7) was supported by the world's seven richest countries (the so-called G-7) and the European Community, which allocated US$258 million for projects in the Amazon and Atlantic Forest regions. The Global Environment Facility (GEF), created in 1990, set aside US$30 million for Brazil, part of which is managed by a national fund called Funbio. GEF also established a small grants program for NGOs, which focused on the cerrado during its pilot phase. The World Bank also made loans for environmental and natural resource management in Rondônia and Mato Grosso, in part to correct environmental and social problems that had been created by the World Bank-funded development of the northwest corridor in the 1980s.

Despite favorable laws, promising institutional arrangements, and external funding, the government has not, on the whole, been effective in controlling damage to the environment. This failure is only in small measure because of the opposition of anti-environmental groups. In greater part, it can be attributed to the traditional separation between official rhetoric and actual practice in Brazil. It is also related to general problems of governance, fiscal crisis, and lingering doubts about appropriate tradeoffs between the environment and development. Some of the most effective governmental action in the environmental area has occurred at the state and local levels in the most developed states and has involved NGOs. In 1994 the PNMA began to stress decentralization and strengthening of state environmental agencies, a tendency that subsequently gained momentum.

Environment - current issues:

deforestation in Amazon Basin destroys the habitat and endangers the existence of a multitude of plant and animal species indigenous to the area; air and water pollution in Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, and several other large cities; land degradation and water pollution caused by improper mining activities

note:

President Cardoso in September 1999 signed into force an environmental crime bill which for the first time defines pollution and deforestation as crimes punishable by stiff fines and jail sentences

Environment - international agreements:

party to:

Antarctic-Environmental Protocol, Antarctic-Marine Living Resources, Antarctic Seals, Antarctic Treaty, Biodiversity, Climate Change, Climate Change-Kyoto Protocol, Desertification, Endangered Species, Environmental Modification, Hazardous Wastes, Law of the Sea, Marine Dumping, Ozone Layer Protection, Ship Pollution, Tropical Timber 83, Tropical Timber 94, Wetlands, Whaling

signed, but not ratified:

none of selected agreements

References

- ↑ Special Note: About 60% of the Amazon Rainforest is part of Brazil.

- ↑ Note: Includes Archipelago de Fernando de Noronha, Rocas Atoll, ♥ Brazil s geography♥Saint Peter and Paul Rocks, Trindade and Martim Vaz Islands.

-

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the Library of Congress Country Studies.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the Library of Congress Country Studies. -

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the CIA World Factbook.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the CIA World Factbook.

External links

- Brazil - from 1565 (English)

- Brazil: of the Noble Class, of Loves, and of Letters… a map from around 1640 (Latin) (English)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||