Gaussian integer

In number theory, a Gaussian integer is a complex number whose real and imaginary part are both integers. The Gaussian integers, with ordinary addition and multiplication of complex numbers, form an integral domain, usually written as Z[i]. This integral domain is a particular case of a commutative ring of quadratic integers. It does not have a total ordering that respects arithmetic.

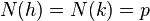

Formally, Gaussian integers are the set

Note that when they are considered within the complex plane the Gaussian integers may be seen to constitute the 2-dimensional integer lattice.

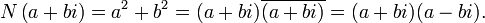

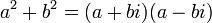

The (arithmetic or field) norm of a Gaussian integer is the square of its absolute value (Euclidean norm) as a complex number and a natural number defined as

(Where the overline over "a+bi" refers to the complex conjugate.)

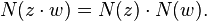

The norm is multiplicative, since the absolute value of complex numbers is multiplicative, i.e., one has

The latter can also be verified by a straightforward check. The units of Z[i] are precisely those elements with norm 1, i.e. the elements 1, −1, i and −i.

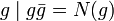

As a principal ideal domain

The Gaussian integers form a principal ideal domain with units 1, −1, i, and −i. If x is a Gaussian integer, the four numbers x, ix, −x, and −ix are called the associates of x. As for every principal ideal domain, the Gaussian integers form also a unique factorization domain.

The prime elements of Z[i] are also known as Gaussian primes. An associate of a Gaussian prime is also a Gaussian prime. The Gaussian primes are symmetric about the real and imaginary axes. The positive integer Gaussian primes are the prime numbers congruent to 3 modulo 4, (sequence A002145 in OEIS). One should not refer to only these numbers as "the Gaussian primes", which refers to all the Gaussian primes, many of which do not lie in Z.[1]

A Gaussian integer  is a Gaussian prime if and only if either:

is a Gaussian prime if and only if either:

- one of a, b is zero and the other is a prime number of the form

(with n a nonnegative integer) or its negative

(with n a nonnegative integer) or its negative  , or

, or - both are nonzero and

is a prime number (which will not be of the form

is a prime number (which will not be of the form  ).

).

The following elaborates on these conditions.

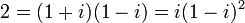

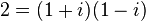

2 is a special case (in the language of algebraic number theory, 2 is the only ramified prime in Z[i]).

The integer 2 factors as  as a Gaussian integer, the second factorisation (in which i is a unit) showing that 2 is divisible by the square of a Gaussian prime; it is the unique prime number with this property.

as a Gaussian integer, the second factorisation (in which i is a unit) showing that 2 is divisible by the square of a Gaussian prime; it is the unique prime number with this property.

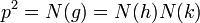

The necessary conditions can be stated as following: if a Gaussian integer is a Gaussian prime, then either its norm is a prime number, or its norm is a square of a prime number. This is because for any Gaussian integer  , notice

, notice

.

.

Here  means “divides”; that is,

means “divides”; that is,  if

if  is a divisor of

is a divisor of  .

.

Now  is an integer, and so can be factored as a product

is an integer, and so can be factored as a product  of prime numbers, by the fundamental theorem of arithmetic. By definition of prime element, if

of prime numbers, by the fundamental theorem of arithmetic. By definition of prime element, if  is a Gaussian prime, then it divides (in Z[i]) some

is a Gaussian prime, then it divides (in Z[i]) some  . Also,

. Also,  divides

divides

, so

, so  in Z.

in Z.

This gives only two options: either the norm of  is a prime number, or the square of a prime number.

is a prime number, or the square of a prime number.

If in fact  for some prime number

for some prime number  , then both

, then both  and

and  divide

divide  . Neither can be a unit, and so

. Neither can be a unit, and so

and

and

where  is a unit. This is to say that either

is a unit. This is to say that either  or

or  , where

, where  .

.

However, not every prime number  is a Gaussian prime. 2 is not because

is a Gaussian prime. 2 is not because  . Neither are prime numbers of the form

. Neither are prime numbers of the form  because Fermat's theorem on sums of two squares assures us they can be written

because Fermat's theorem on sums of two squares assures us they can be written  for integers

for integers  and

and  , and

, and  . The only type of prime numbers remaining are of the form

. The only type of prime numbers remaining are of the form  .

.

Prime numbers of the form  are also Gaussian primes. For suppose

are also Gaussian primes. For suppose  for

for  , and it can be factored

, and it can be factored  . Then

. Then  . If the factorization is non-trivial, then

. If the factorization is non-trivial, then  . But no sum of squares of integers can be written

. But no sum of squares of integers can be written  . So the factorization must have been trivial and

. So the factorization must have been trivial and  is a Gaussian prime.

is a Gaussian prime.

If  is a Gaussian integer whose norm is a prime number, then

is a Gaussian integer whose norm is a prime number, then  is a Gaussian prime, because the norm is multiplicative.

is a Gaussian prime, because the norm is multiplicative.

As an integral closure

The ring of Gaussian integers is the integral closure of Z in the field of Gaussian rationals Q(i) consisting of the complex numbers whose real and imaginary part are both rational.

As a Euclidean domain

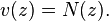

It is easy to see graphically that every complex number is within  units of a Gaussian integer.

units of a Gaussian integer.

Put another way, every complex number (and hence every Gaussian integer) has a maximal distance of

units to some multiple of z, where z is any Gaussian integer; this turns Z[i] into a Euclidean domain, where

Historical background

The ring of Gaussian integers was introduced by Carl Friedrich Gauss in his second monograph on quartic reciprocity (1832) (see ). The theorem of quadratic reciprocity (which he had first succeeded in proving in 1796) relates the solvability of the congruence x2 ≡ q (mod p) to that of x2 ≡ p (mod q). Similarly, cubic reciprocity relates the solvability of x3 ≡ q (mod p) to that of x3 ≡ p (mod q), and biquadratic (or quartic) reciprocity is a relation between x4 ≡ q (mod p) and x4 ≡ p (mod q). Gauss discovered that the law of biquadratic reciprocity and its supplements were more easily stated and proved as statements about "whole complex numbers" (i.e. the Gaussian integers) than they are as statements about ordinary whole numbers (i.e. the integers).

In a footnote he notes that the Eisenstein integers are the natural domain for stating and proving results on cubic reciprocity and indicates that similar extensions of the integers are the appropriate domains for studying higher reciprocity laws.

This paper not only introduced the Gaussian integers and proved they are a unique factorization domain, it also introduced the terms norm, unit, primary, and associate, which are now standard in algebraic number theory.

Unsolved problems

Most of the unsolved problems are related to the repartition in the plane of the Gaussian primes.

- Gauss's circle problem does not deal with the Gaussian integers per se, but instead asks for the number of lattice points inside a circle of a given radius centered at the origin. This is equivalent to determining the number of Gaussian integers with norm less than a given value.

There are also conjectures and unsolved problems about the Gaussian primes. Two of them are:

- The real and imaginary axes have the infinite set of Gaussian primes 3, 7, 11, 19, ... and their associates. Are there any other lines that have infinitely many Gaussian primes on them? In particular, are there infinitely many Gaussian primes of the form 1+ki?[2]

- Is it possible to walk to infinity using the Gaussian primes as stepping stones and taking steps of bounded length? This is known as the Gaussian moat problem; it was posed in 1962 by Basil Gordon and remains unsolved.[3][4]

See also

- Quadratic integer

- Hurwitz quaternion

- Eisenstein integer

- Algebraic integer

- Kummer ring

- Proofs of Fermat's theorem on sums of two squares

- Proofs of quadratic reciprocity

- Splitting of prime ideals in Galois extensions describes the structure of prime ideals in the Gaussian integers

- Table of Gaussian integer factorizations

Notes

- ↑ , OEIS sequence A002145 "COMMENT" section

- ↑ Ribenboim, Ch.III.4.D Ch. 6.II, Ch. 6.IV (Hardy & Littlewood's conjecture E and F)

- ↑ Gethner, Ellen; Wagon, Stan; Wick, Brian (1998). "A stroll through the Gaussian primes". The American Mathematical Monthly 105 (4): 327–337. doi:10.2307/2589708. MR 1614871. Zbl 0946.11002.

- ↑ Guy, Richard K. (2004). Unsolved problems in number theory (3rd ed.). Springer-Verlag. pp. 55–57. ISBN 978-0-387-20860-2. Zbl 1058.11001.

References

- C. F. Gauss, Theoria residuorum biquadraticorum. Commentatio secunda., Comm. Soc. Reg. Sci. Göttingen 7 (1832) 1-34; reprinted in Werke, Georg Olms Verlag, Hildesheim, 1973, pp. 93–148.

- Kleiner, Israel (1998). "From Numbers to Rings: The Early History of Ring Theory". Elem. Math. 53 (1): 18–35. doi:10.1007/s000170050029. Zbl 0908.16001.

- Ribenboim, Paulo (1996). The New Book of Prime Number Records (3rd ed.). New York: Springer. ISBN 0-387-94457-5. Zbl 0856.11001.

External links

- www.alpertron.com.ar/GAUSSIAN.HTM is a Java applet that evaluates expressions containing Gaussian integers and factors them into Gaussian primes.

- www.alpertron.com.ar/GAUSSPR.HTM is a Java applet that features a graphical view of Gaussian primes.

- Henry G. Baker (1993) Complex Gaussian Integers for 'Gaussian Graphics', ACM SIGPLAN Notices, Vol. 28, Issue 11. DOI 10.1145/165564.165571 (html)

- IMO Compendium text on quadratic extensions and Gaussian Integers in problem solving

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Landau's Problems", MathWorld.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![{\mathbb {Z}}[i]=\{a+bi\mid a,b\in {\mathbb {Z}}\},\ {\mbox{where}}\ i^{2}=-1.](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/5/5/7/b/557b489dbb9eb669ddfe6208988c5e35.png)