Gambler's fallacy

The gambler's fallacy, also known as the Monte Carlo fallacy or the fallacy of the maturity of chances, is the mistaken belief that if something happens more frequently than normal during some period, then it will happen less frequently in the future (presumably as a means of balancing nature). In situations where what is being observed is truly random (i.e. independent trials of a random process), this belief, though appealing to the human mind, is false. This fallacy can arise in many practical situations although it is most strongly associated with gambling where such mistakes are common among players.

The use of the term Monte Carlo fallacy originates from the most famous example of this phenomenon, which occurred in a Monte Carlo Casino in 1913.[1][2]

An example: coin-tossing

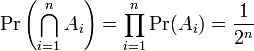

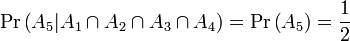

The gambler's fallacy can be illustrated by considering the repeated toss of a fair coin. With a fair coin, the outcomes in different tosses are statistically independent and the probability of getting heads on a single toss is exactly 1⁄2 (one in two). It follows that the probability of getting two heads in two tosses is 1⁄4 (one in four) and the probability of getting three heads in three tosses is 1⁄8 (one in eight). In general, if we let Ai be the event that toss i of a fair coin comes up heads, then we have,

.

.

Now suppose that we have just tossed four heads in a row, so that if the next coin toss were also to come up heads, it would complete a run of five successive heads. Since the probability of a run of five successive heads is only 1⁄32 (one in thirty-two), a person subject to the gambler's fallacy might believe that this next flip was less likely to be heads than to be tails. However, this is not correct, and is a manifestation of the gambler's fallacy; the event of 5 heads in a row and the event of "first 4 heads, then a tails" are equally likely, each having probability 1⁄32. Given that the first four rolls turn up heads, the probability that the next toss is a head is in fact,

.

.

While a run of five heads is only 1⁄32 = 0.03125, it is only that before the coin is first tossed. After the first four tosses the results are no longer unknown, so their probabilities are 1. Reasoning that it is more likely that the next toss will be a tail than a head due to the past tosses, that a run of luck in the past somehow influences the odds in the future, is the fallacy.

Explaining why the probability is 1/2 for a fair coin

We can see from the above that, if one flips a fair coin 21 times, then the probability of 21 heads is 1 in 2,097,152. However, the probability of flipping a head after having already flipped 20 heads in a row is simply 1⁄2. This is an application of Bayes' theorem.

This can also be seen without knowing that 20 heads have occurred for certain (without applying of Bayes' theorem). Consider the following two probabilities, assuming a fair coin:

- probability of 20 heads, then 1 tail = 0.520 × 0.5 = 0.521

- probability of 20 heads, then 1 head = 0.520 × 0.5 = 0.521

The probability of getting 20 heads then 1 tail, and the probability of getting 20 heads then another head are both 1 in 2,097,152. Therefore, it is equally likely to flip 21 heads as it is to flip 20 heads and then 1 tail when flipping a fair coin 21 times. Furthermore, these two probabilities are equally as likely as any other 21-flip combinations that can be obtained (there are 2,097,152 total); all 21-flip combinations will have probabilities equal to 0.521, or 1 in 2,097,152. From these observations, there is no reason to assume at any point that a change of luck is warranted based on prior trials (flips), because every outcome observed will always have been as likely as the other outcomes that were not observed for that particular trial, given a fair coin. Therefore, just as Bayes' theorem shows, the result of each trial comes down to the base probability of the fair coin: 1⁄2.

Other examples

There is another way to emphasize the fallacy. As already mentioned, the fallacy is built on the notion that previous failures indicate an increased probability of success on subsequent attempts. This is, in fact, the inverse of what actually happens, even on a fair chance of a successful event, given a set number of iterations. Assume a fair 16-sided die, where a win is defined as rolling a 1. Assume a player is given 16 rolls to obtain at least one win (1−Pr(rolling no 1's in 16 rolls)). The low winning odds are just to make the change in probability more noticeable. The probability of having at least one win in the 16 rolls is:

However, assume now that the first roll was a loss (93.75% chance of that, 15⁄16). The player now only has 15 rolls left and, according to the fallacy, should have a higher chance of winning since one loss has occurred. His chances of having at least one win are now:

Simply by losing one toss the player's probability of winning dropped by 2 percentage points. By the time this reaches 5 losses (11 rolls left), his probability of winning on one of the remaining rolls will have dropped to ~50%. The player's odds for at least one win in those 16 rolls has not increased given a series of losses; his odds have decreased because he has fewer iterations left to win. In other words, the previous losses in no way contribute to the odds of the remaining attempts, but there are fewer remaining attempts to gain a win, which results in a lower probability of obtaining it.

The player becomes more likely to lose in a set number of iterations as he fails to win, and eventually his probability of winning will again equal the probability of winning a single toss, when only one toss is left: 6.25% in this instance.

Some lottery players will choose the same numbers every time, or intentionally change their numbers, but both are equally likely to win any individual lottery draw. Copying the numbers that won the previous lottery draw gives an equal probability, although a rational gambler might attempt to predict other players' choices and then deliberately avoid these numbers. Low numbers (below 31 and especially below 12) are popular because people play birthdays as their so-called lucky numbers; hence a win in which these numbers are over-represented is more likely to result in a shared payout.

A joke told among mathematicians demonstrates the nature of the fallacy. When flying on an aircraft, a man decides to always bring a bomb with him. "The chances of an aircraft having a bomb on it are very small," he reasons, "and certainly the chances of having two are almost none!" A similar example is in the book The World According to Garp when the hero Garp decides to buy a house a moment after a small plane crashes into it, reasoning that the chances of another plane hitting the house have just dropped to zero.

Reverse fallacy

The reversal is also a fallacy (not to be confused with the inverse gambler's fallacy) in which a gambler may instead decide, after a consistent tendency towards tails, that tails are more likely out of some mystical preconception that fate has thus far allowed for consistent results of tails. Believing the odds to favor tails, the gambler sees no reason to change to heads. Again, the fallacy is the belief that the "universe" somehow carries a memory of past results which tend to favor or disfavor future outcomes.

Caveats

In most illustrations of the gambler's fallacy and the reversed gambler's fallacy, the trial (e.g. flipping a coin) is assumed to be fair. In practice, this assumption may not hold.

For example, if one flips a fair coin 21 times, then the probability of 21 heads is 1 in 2,097,152 (above). If the coin is fair, then the probability of the next flip being heads is 1/2. However, because the odds of flipping 21 heads in a row is so slim, it may well be that the coin is somehow biased towards landing on heads, or that it is being controlled by hidden magnets, or similar.[3] In this case, the smart bet is "heads" because the Bayesian inference from the empirical evidence — 21 "heads" in a row — suggests that the coin is likely to be biased toward "heads", contradicting the general assumption that the coin is fair.

The opening scene of the play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead by Tom Stoppard discusses these issues as one man continually flips heads and the other considers various possible explanations.

Childbirth

Instances of the gambler’s fallacy being applied to childbirth can be traced all the way back to 1796, in Pierre-Simon Laplace’s A Philosophical Essay on Probabilities. Laplace wrote of the ways in which men calculated their probability of having sons: "I have seen men, ardently desirous of having a son, who could learn only with anxiety of the births of boys in the month when they expected to become fathers. Imagining that the ratio of these births to those of girls ought to be the same at the end of each month, they judged that the boys already born would render more probable the births next of girls." In short, the expectant fathers feared that if more sons were born in the surrounding community, then they themselves would be more likely to have a daughter.[4]

Some expectant parents believe that, after having multiple children of the same sex, they are "due" to have a child of the opposite sex. While the Trivers–Willard hypothesis predicts that birth sex is dependent on living conditions (i.e. more male children are born in "good" living conditions, while more female children are born in poorer living conditions), the probability of having a child of either gender is still generally regarded as near 50%.

Monte Carlo Casino

The most famous example of the gambler’s fallacy occurred in a game of roulette at the Monte Carlo Casino on August 18, 1913,[5] when the ball fell in black 26 times in a row. This was an extremely uncommon occurrence, although no more nor less common than any of the other 67,108,863 sequences of 26 red or black. Gamblers lost millions of francs betting against black, reasoning incorrectly that the streak was causing an "imbalance" in the randomness of the wheel, and that it had to be followed by a long streak of red.[1]

Non-examples of the fallacy

There are many scenarios where the gambler's fallacy might superficially seem to apply, when it actually does not. When the probability of different events is not independent, the probability of future events can change based on the outcome of past events (see statistical permutation). Formally, the system is said to have memory. An example of this is cards drawn without replacement. For example, if an ace is drawn from a deck and not reinserted, the next draw is less likely to be an ace and more likely to be of another rank. The odds for drawing another ace, assuming that it was the first card drawn and that there are no jokers, have decreased from 4⁄52 (7.69%) to 3⁄51 (5.88%), while the odds for each other rank have increased from 4⁄52 (7.69%) to 4⁄51 (7.84%). This type of effect is what allows card counting systems to work (for example in the game of blackjack).

The reversed gambler's fallacy may appear to apply in the story of Joseph Jagger, who hired clerks to record the results of roulette wheels in Monte Carlo. He discovered that one wheel favored nine numbers and won large sums of money until the casino started rebalancing the roulette wheels daily. In this situation, the observation of the wheel's behavior provided information about the physical properties of the wheel rather than its "probability" in some abstract sense, a concept which is the basis of both the gambler's fallacy and its reversal. Even a biased wheel's past results will not affect future results, but the results can provide information about what sort of results the wheel tends to produce. However, if it is known for certain that the wheel is completely fair, then past results provide no information about future ones.

The outcome of future events can be affected if external factors are allowed to change the probability of the events (e.g., changes in the rules of a game affecting a sports team's performance levels). Additionally, an inexperienced player's success may decrease after opposing teams discover his weaknesses and exploit them. The player must then attempt to compensate and randomize his strategy. Such analysis is part of game theory.

Non-example: unknown probability of event

When the probabilities of repeated events are not known, outcomes may not be equally probable. In the case of coin tossing, as a run of heads gets longer and longer, the likelihood that the coin is biased towards heads increases. If one flips a coin 21 times in a row and obtains 21 heads, one might rationally conclude a high probability of bias towards heads, and hence conclude that future flips of this coin are also highly likely to be heads. In fact, Bayesian inference can be used to show that when the long-run proportion of different outcomes are unknown but exchangeable (meaning that the random process from which they are generated may be biased but is equally likely to be biased in any direction) and that previous observations demonstrate the likely direction of the bias, such that the outcome which has occurred the most in the observed data is the most likely to occur again.[6]

Psychology behind the fallacy

Origins

Gambler's fallacy arises out of a belief in the law of small numbers, or the erroneous belief that small samples must be representative of the larger population. According to the fallacy, "streaks" must eventually even out in order to be representative.[7] Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman first proposed that the gambler's fallacy is a cognitive bias produced by a psychological heuristic called the representativeness heuristic, which states that people evaluate the probability of a certain event by assessing how similar it is to events they have experienced before, and how similar the events surrounding those two processes are.[8][9] According to this view, "after observing a long run of red on the roulette wheel, for example, most people erroneously believe that black will result in a more representative sequence than the occurrence of an additional red",[10] so people expect that a short run of random outcomes should share properties of a longer run, specifically in that deviations from average should balance out. When people are asked to make up a random-looking sequence of coin tosses, they tend to make sequences where the proportion of heads to tails stays closer to 0.5 in any short segment than would be predicted by chance (insensitivity to sample size);[11] Kahneman and Tversky interpret this to mean that people believe short sequences of random events should be representative of longer ones.[12] The representativeness heuristic is also cited behind the related phenomenon of the clustering illusion, according to which people see streaks of random events as being non-random when such streaks are actually much more likely to occur in small samples than people expect.[13]

The gambler's fallacy can also be attributed to the mistaken belief that gambling (or even chance itself) is a fair process that can correct itself in the event of streaks, otherwise known as the just-world hypothesis.[14] Other researchers believe that individuals with an internal locus of control—i.e., people who believe that the gambling outcomes are the result of their own skill—are more susceptible to the gambler's fallacy because they reject the idea that chance could overcome skill or talent.[15]

Variations of the gambler's fallacy

Some researchers believe that there are actually two types of gambler's fallacy: Type I and Type II. Type I is the "classic" gambler's fallacy, when individuals believe that a certain outcome is "due" after a long streak of another outcome. Type II gambler's fallacy, as defined by Gideon Keren and Charles Lewis, occurs when a gambler underestimates how many observations are needed to detect a favorable outcome (such as watching a roulette wheel for a length of time and then betting on the numbers that appear most often). Detecting a bias that will lead to a favorable outcome takes an impractically large amount of time and is very difficult, if not impossible, to do; therefore people fall prey to the Type II gambler's fallacy.[16] The two types are different in that Type I wrongly assumes that gambling conditions are fair and perfect, while Type II assumes that the conditions are biased, and that this bias can be detected after a certain amount of time.

Another variety, known as the retrospective gambler's fallacy, occurs when individuals judge that a seemingly rare event must come from a longer sequence than a more common event does. For example, people believe that an imaginary sequence of die rolls is more than three times as long when a set of three 6's is observed as opposed to when there are only two 6's. This effect can be observed in isolated instances, or even sequentially. A real world example is that when a teenager becomes pregnant after having unprotected sex, people assume that she has been engaging in unprotected sex for longer than someone who has been engaging in unprotected sex and is not pregnant.[17]

Relationship to hot-hand fallacy

Another psychological perspective states that gambler's fallacy can be seen as the counterpart to basketball's hot-hand fallacy, in which people tend to predict the same outcome of the last event (positive recency)—that a high scorer will continue to score. In gambler's fallacy, however, people predict the opposite outcome of the last event (negative recency)—that, for example, since the roulette wheel has landed on black the last six times, it is due to land on red the next. Ayton and Fischer have theorized that people display positive recency for the hot-hand fallacy because the fallacy deals with human performance, and that people do not believe that an inanimate object can become "hot."[18] Human performance is not perceived as "random," and people are more likely to continue streaks when they believe that the process generating the results is nonrandom.[7] Usually, when a person exhibits the gambler's fallacy, they are more likely to exhibit the hot-hand fallacy as well, suggesting that one construct is responsible for the two fallacies.[19]

The difference between the two fallacies is also represented in economic decision-making. A study by Huber, Kirchler, and Stockl (2010) examined how the hot hand and the gambler's fallacy are exhibited in the financial market. The researchers gave their participants a choice: they could either bet on the outcome of a series of coin tosses, use an "expert" opinion to sway their decision, or choose a risk-free alternative instead for a smaller financial reward. Participants turned to the "expert" opinion to make their decision 24% of the time based on their past experience of success, which exemplifies the hot-hand. If the expert was correct, 78% of the participants chose the expert's opinion again, as opposed to 57% doing so when the expert was wrong. The participants also exhibited the gambler's fallacy, with their selection of either heads or tails decreasing after noticing a streak of that outcome. This experiment helped bolster Ayton and Fischer's theory that people put more faith in human performance than they do in seemingly random processes.[20]

Neurophysiology

While the representativeness heuristic and other cognitive biases are the most commonly cited cause of the gambler's fallacy, research suggests that there may be a neurological component to it as well. Functional magnetic resonance imaging has revealed that, after losing a bet or gamble ("riskloss"), the frontoparietal network of the brain is activated, resulting in more risk-taking behavior. In contrast, there is decreased activity in the amygdala, caudate, and ventral striatum after a riskloss. Activation in the amygdala is negatively correlated with gambler's fallacy—the more activity exhibited in the amygdala, the less likely an individual is to fall prey to the gambler's fallacy. These results suggest that gambler's fallacy relies more on the prefrontal cortex (responsible for executive, goal-directed processes) and less on the brain areas that control affective decision-making.

The desire to continue gambling or betting is controlled by the striatum, which supports a choice-outcome contingency learning method. The striatum processes the errors in prediction and the behavior changes accordingly. After a win, the positive behavior is reinforced and after a loss, the behavior is conditioned to be avoided. In individuals exhibiting the gambler's fallacy, this choice-outcome contingency method is impaired, and they continue to make risks after a series of losses.[21]

Possible solutions

The gambler's fallacy is a deep-seated cognitive bias and therefore very difficult to eliminate. For the most part, educating individuals about the nature of randomness has not proven effective in reducing or eliminating any manifestation of the gambler's fallacy. Participants in an early study by Beach and Swensson (1967) were shown a shuffled deck of index cards with shapes on them, and were told to guess which shape would come next in a sequence. The experimental group of participants was informed about the nature and existence of the gambler's fallacy, and were explicitly instructed not to rely on "run dependency" to make their guesses. The control group was not given this information. Even so, the response styles of the two groups were similar, indicating that the experimental group still based their choices on the length of the run sequence. Clearly, instructing individuals about randomness is not sufficient in lessening the gambler's fallacy.[22]

It does appear, however, that an individual's susceptibility to the gambler's fallacy decreases with age. Fischbein and Schnarch (1997) administered a questionnaire to five groups: students in grades 5, 7, 9, 11, and college students specializing in teaching mathematics. None of the participants had received any prior education regarding probability. The question was, "Ronni flipped a coin three times and in all cases heads came up. Ronni intends to flip the coin again. What is the chance of getting heads the fourth time?" The results indicated that as the older the students got, the less likely they were to answer with "smaller than the chance of getting tails", which would indicate a negative recency effect. 35% of the 5th graders, 35% of the 7th graders, and 20% of the 9th graders exhibited the negative recency effect. Only 10% of the 11th graders answered this way, however, and none of the college students did. Fischbein and Schnarch therefore theorized that an individual's tendency to rely on the representativeness heuristic and other cognitive biases can be overcome with age.[23]

Another possible solution that could be seen as more proactive comes from Roney and Trick, Gestalt psychologists who suggest that the fallacy may be eliminated as a result of grouping. When a future event (ex: a coin toss) is described as part of a sequence, no matter how arbitrarily, a person will automatically consider the event as it relates to the past events, resulting in the gambler's fallacy. When a person considers every event as independent, however, the fallacy can be greatly reduced.[24]

In their experiment, Roney and Trick told participants that they were betting on either two blocks of six coin tosses, or on two blocks of seven coin tosses. The fourth, fifth, and sixth tosses all had the same outcome, either three heads or three tails. The seventh toss was grouped with either the end of one block, or the beginning of the next block. Participants exhibited the strongest gambler's fallacy when the seventh trial was part of the first block, directly after the sequence of three heads or tails. Additionally, the researchers pointed out how insidious the fallacy can be—the participants that did not show the gambler's fallacy showed less confidence in their bets and bet fewer times than the participants who picked "with" the gambler's fallacy. However, when the seventh trial was grouped with the second block (and was therefore perceived as not being part of a streak), the gambler's fallacy did not occur.

Roney and Trick argue that a solution to gambler's fallacy could be, instead of teaching individuals about the nature of randomness, training people to treat each event as if it is a beginning and not a continuation of previous events. This would prevent people from gambling when they are losing in the vain hope that their chances of winning are due to increase.

See also

- Availability heuristic

- Gambler's conceit

- Gambler's ruin

- Inverse gambler's fallacy

- Hot hand fallacy

- Law of averages

- Martingale (betting system)

- Mean reversion (finance)

- Regression toward the mean

- Statistical regularity

- Ulam spiral

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Lehrer, Jonah (2009). How We Decide. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-618-62011-1.

- ↑ Blog - "Fallacy Files" What happened at Monte Carlo in 1913.

- ↑ Martin Gardner, Entertaining Mathematical Puzzles, Dover Publications, 69-70.

- ↑ Barron, G. and Leider, S. (2010). The role of experience in the gambler's fallacy. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 23, 117-129.

- ↑ "Roulette", in The Universal Book of Mathematics: From Abracadabra to Zeno's Paradoxes, by David Darling (John Wiley & Sons, 2004) p278

- ↑ O'Neill, B. and Puza, B.D. (2004) Dice have no memories but I do: A defence of the reverse gambler's belief. . Reprinted in abridged form as O'Neill, B. and Puza, B.D. (2005) In defence of the reverse gambler's belief. The Mathematical Scientist 30(1), pp. 13–16.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Burns, B. D. and Corpus, B. (2004). Randomness and inductions from streaks: "Gambler's fallacy" versus "hot hand". Psychonomic Bulletin and Review. 11, 179-184

- ↑ Tversky, Amos; Daniel Kahneman (1974). "Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases". Science 185 (4157): 1124–1131. doi:10.1126/science.185.4157.1124. PMID 17835457.

- ↑ Tversky, Amos; Daniel Kahneman (1971). "Belief in the law of small numbers". Psychological Bulletin 76 (2): 105–110. doi:10.1037/h0031322.

- ↑ Tversky & Kahneman, 1974.

- ↑ Tune, G. S. (1964). "Response preferences: A review of some relevant literature". Psychological Bulletin 61 (4): 286–302. doi:10.1037/h0048618. PMID 14140335.

- ↑ Tversky & Kahneman, 1971.

- ↑ Gilovich, Thomas (1991). How we know what isn't so. New York: The Free Press. pp. 16–19. ISBN 0-02-911706-2.

- ↑ Rogers, P. (1998). "The cognitive psychology of lottery gambling: A theoretical review". Journal of Gambling Studies, 14, 111-134

- ↑ Sundali, J. and Croson, R. (2006). "Biases in casino betting: The hot hand and the gambler's fallacy". Judgment and Decision Making, 1, 1-12.

- ↑ Keren, G. and Lewis, C. (1994). "The two fallacies of gamblers: Type I and Type II". Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 60, 75-89.

- ↑ Oppenheimer, D. M. and Monin, B. (2009). "The retrospective gambler's fallacy: Unlikely events, constructing the past, and multiple universes". Judgment and Decision Making, 4, 326-334.

- ↑ Ayton, P.; Fischer, I. (2004). "The hot-hand fallacy and the gambler's fallacy: Two faces of subjective randomness?". Memory and Cognition 32: 1369–1378.

- ↑ Sundali, J.; Croson, R. (2006). "Biases in casino betting: The hot hand and the gambler's fallacy". Judgment and Decision Making 1: 1–12.

- ↑ Huber, J.; Kirchler, M.; Stockl, T. (2010). "The hot hand belief and the gambler's fallacy in investment decisions under risk". Theory and Decision 68: 445–462.

- ↑ Xue, G.; Lu, Z.; Levin, I. P.; Bechara, A. (2011). "An fMRI study of risk-taking following wins and losses: Implications for the gambler's fallacy". Human Brain Mapping 32: 271–281.

- ↑ Beach, L. R.; Swensson, R. G. (1967). "Instructions about randomness and run dependency in two-choice learning". Journal of Experimental Psychology 75: 279–282.

- ↑ Fischbein, E.; Schnarch, D. (1997). "The evolution with age of probabilistic, intuitively based misconceptions". Journal for Research in Mathematics Education 28: 96–105.

- ↑ Roney, C. J.; Trick, L. M. (2003). "Grouping and gambling: A gestalt approach to understanding the gambler's fallacy". Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology 57: 69–75.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![1-\left[{\frac {15}{16}}\right]^{{16}}\,=\,64.39\%](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/0/c/1/b/0c1b7920319df20281ef7912f92e3472.png)

![1-\left[{\frac {15}{16}}\right]^{{15}}\,=\,62.02\%](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/1/8/1/5/181531b616afa362f4b7273f3447325b.png)