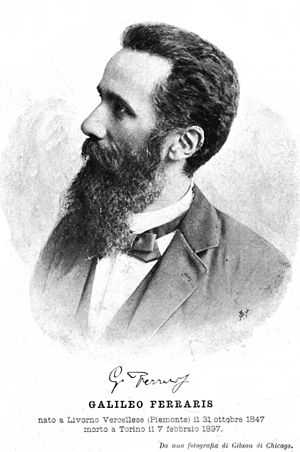

Galileo Ferraris

| Galileo Ferraris | |

|---|---|

Galileo Ferraris | |

| Born |

31 October 1847 Livorno Vercellese, Kingdom of Sardinia |

| Died |

7 February 1897 Turin, Kingdom of Italy |

| Nationality | Italy |

| Fields | physics; engineering |

| Known for | Alternating current |

Galileo Ferraris (31 October 1847 – 7 February 1897) was an Italian physicist and electrical engineer, noted mostly for the studies and independent discovery of the rotating magnetic field, a basic working principle of the induction motor.[1][2][3] Ferraris has published an extensive and complete monograph on the experimental results obtained with open-circuit transformers of the type designed by the power engineers Lucien Gaulard and John Dixon Gibbs.

Biography

Born at Livorno Vercellese (Kingdom of Sardinia), Ferraris gained a master's degree in engineering and became an assistant of technical physics near the Regal Italian Industrial Museum. Ferraris independently researched the rotary magnetic field in 1885. Ferraris experimented with different types of asynchronous electric motors. The research and his studies resulted in the development of an alternating-current motor. On the 11th of March 1888, Ferraris published his research in a paper to the Royal Academy of Sciences in Turin (two months later Nikola Tesla gained U.S. Patent 381,968, application filed October 12, 1887. Serial Number 252,132). These motors operating by systems of alternating currents displaced from one another in phase by definite amounts and producing what is known as the rotating magnetic field. This invention seems destined to be one of the most important that has been made in the history of electricity. The result of the introduction of polyphase systems has been the ability to transmit power economically for considerable distances, and, as this directly operated to make possible the utilization of water-power in remote places and the distribution of power over large areas, the immediate outcome of the polyphase system was power transmission; and the outcome of power transmission almost surely will be the gradual supersession of coal and the harnessing of the waste forces of Nature to do useful work.

In 1889, Ferraris worked at the Italian Industrial Institution, a school of electrical engineering (the first school of this kind in Italy; subsequently incorporated in the Politecnico di Torino). In 1896, Ferraris joined the Italian Electrotechnical Association and became the first national president of the organization.

Galileo Ferraris researched the fundamental properties of dioptric instruments and made elementary representation of the theory and its applications. His work contains a detailed description of the geometric dioptrics for uncentered systems. He provided a greater generality as previously found in the telescopic system treatments, so the one in which the fundamental points were missing. In the second main sections, the results obtained are applied to optical instruments. This was dealt with in great detail the magnification, field of view and the brightness of the instrument. The field denned as the author of that cone opening angle, the tip of the first main points of the lens and its base formed by the parts of the object in view, will possess the same brightness. The eye is not treated.[4]

Memorials

The City of Turin honored the services which Ferraris rendered to science.[5] A general committee proposed addition of a Royal Industrial Museum of Turin, a permanent monument commemorating his scientific and industrial achievements.[5]

Publications

- Sulle differenze di fase delle correnti e sulla dissipazione di energia nei trasformatori, by Prof. Galileo Ferraris (Turin, 1887).

References

- ↑ Alternating currents of electricity: their generation, measurement, distribution, and application by Gisbert Kapp, William Stanley, Jr.. Johnston, 1893. p. 140. [cf., This direction has been first indicated by Professor Galileo Ferraris, of Turin, some six years ago. Quite independent of Ferraris, the same discovery was also made by Nikola Tesla, of New York; and since the practical importance of the discovery has been recognized, quite a host of original discoverers have come forward, each claiming to be the first.]

- ↑ Larned, J. N., & Reiley, A. C. (1901). History for ready reference: From the best historians, biographers, and specialists; their own words in a complete system of history. Springfield, Mass: The C.A. Nichols Co.. p. 440. [cf., At about the same time [1888], Galileo Ferraris, in Italy, and Nikola Tesla, in the United States, brought out motors operating by systems of alternating currents displaced from one another in phase by definite amounts and producing what is known as the rotating magnetic field.]

- ↑ The Electrical engineer. (1888). London: Biggs & Co. p., 239. [cf., "[...] new application of the alternating current in the production of rotary motion was made known almost simultaneously by two experimenters, Nikola Tesla and Galileo Ferraris, and the subject has attracted general attention from the fact that no commutator or connection of any kind with the armature was required."]

- ↑ G. Reimer (1886). Die Fortschritte der Physik (tr., The progress of physics), Volume 35. Berlin etc.: Deutsche physikalische Gesellschaft etc.. Page 354.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 The Electrical review 40. IPC Electrical-Electronic Press. 1897. pp. 357–. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

Sulle differenze di fase delle correnti e sulla dissipazione di energia nei trasformatori

Further reading

Dibner, Bern (1970–80). "Ferraris, Galileo". Dictionary of Scientific Biography 4. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 588–9. ISBN 0684101149.

External links

- Katz, Eugenii, "Galileo Ferraris". Biosensors & Bioelectronics.

- Istituto Elettrotecnico Nazionale Galileo Ferraris (IEN) – Official web site (English)

- Who Invented the Polyphase Electric Motor?

|