Géza Maróczy

| Géza Maróczy | |

|---|---|

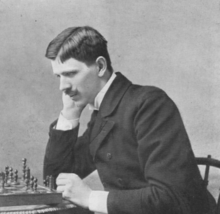

Géza Maróczy | |

| Full name | Géza Maróczy |

| Country | Hungary |

| Born |

3 March 1870 Szeged, Hungary |

| Died |

29 May 1951 (aged 81) Budapest, Hungary |

| Title | Grandmaster (1950) |

Géza Maróczy (Hungarian pronunciation: [ˈmɒroːtsi ˈɡeːzɒ]; 3 March 1870 – 29 May 1951) was a leading Hungarian chess Grandmaster, one of the best players in the world in his time. He was also a practicing engineer.

Early career

Géza Maróczy was born in Szeged, Hungary on March 3, 1870. He won the "minor" tournament at Hastings 1895, and over the next ten years he won several first prizes in international events. Between 1902 and 1908, he took part in thirteen tournaments and won five first prizes and five second prizes. In 1906 he agreed to terms for a World Championship match with Emanuel Lasker, but political problems in Cuba, where the match was to be played, caused the arrangements to be canceled.

Retirement and return

After 1908, Maróczy retired from international chess to devote more time to his profession as a clerk. He worked as an auditor and made a good career at the Center of Trade Unions and Social Insurance. When the Communists came briefly to power he was a chief auditor at Educational Ministry. After the Communist government was overthrown he couldn't get a job. He did make a brief return to chess after World War I, with some success, and today the Maróczy bind (see below) bears his name. At the turn of the year 1927/8, he demolished the 1924 champion of Hungary, Géza Nagy, in a match by +5−0=3. With him at the head, Hungary won the first two Chess Olympiads in London (1927) and The Hague (1928).

In 1950, FIDE awarded him the title of Grandmaster.

Style

| This section uses algebraic notation to describe chess moves. |

Maróczy's style, though sound, was very defensive in nature. His successful defences of the Danish Gambit against Jacques Mieses[1] and Karl Helling,[2] involving judicious return of the sacrificed material for advantage, were used as models of defensive play by Max Euwe and Kramer in their two-volume series on the middlegame. Aron Nimzowitsch, in My System, used Maróczy's win against Hugo Süchting (in Barmen 1905) as a model of restraining the opponent before breaking through.[3] But he could also play spectacular chess on occasion, such as his famous victory over the noted attacking player David Janowski (Munich 1900).[4]

His handling of queen endgames was also highly respected, such as against Frank Marshall, from Karlsbad 1907, showing superior queen activity.[5]

The Maróczy bind is a formation White may adopt against some variations of the Sicilian Defence. By placing pawns on e4 and c4, White slightly reduces his attacking prospects but also greatly inhibits Black's counterplay.

Assessment

Maróczy had respectable lifetime scores against most of the top players of his day. But he had negative scores against the world chess champions: Wilhelm Steinitz (+1−2=1), Emanuel Lasker (+1−4=2), José Raúl Capablanca (+0−3=5) and Alexander Alekhine (+0−6=5); except for Max Euwe whom he beat (+4−3=15). But Maróczy's defensive style was often more than sufficient to beat the leading attacking players of his day such as Joseph Henry Blackburne (+5−0=3), Mikhail Chigorin (+6−4=7), Frank Marshall (+11−6=8), David Janowski (+10−5=5), Efim Bogoljubov (+7−4=4) and Frederick Yates (+8−0=1).

Capablanca held Maróczy in high esteem. In a lecture given in the early 1940s, Capablanca called Maróczy "very gentlemanly and correct" and "a kindly figure", praised the Maróczy Bind as an important contribution to opening theory, credited him as a "good teacher" who greatly helped Vera Menchik reach the top of women's chess, and "one of the greatest masters of his time." Capablanca wrote (as cited by Edward Winter's compendium on Capablanca):As a chessplayer he was a little lacking in imagination and aggressive spirit. His positional judgement, the greatest quality of the true master, was excellent. A very accurate player and an excellent endgame artist, he became famous as an expert on queen endings. In a tournament many years ago he won a knight endgame against the Viennese master Marco which has gone into history as one of the classic endings of this type. (Capablanca was referring to Marco–Maroczy, 1899.)

Concerning the relative strength of Maróczy and the best young masters of today, my opinion is that, with the exception of Botvinnik and Keres, Maróczy in his time was superior to all the other players of today.

References

- ↑ Mieses vs Maroczy, 1903 Chessgames.com

- ↑ Maroczy vs Helling, 1936 Chessgames.com

- ↑ Maroczy vs Suechting, 1905 Chessgames.com

- ↑ Janowski vs Maroczy, 1900 Chessgames.com

- ↑ Maroczy vs Marshall, 1907 Chessgames.com

External links

- Kmoch, Hans (2004). "Grandmasters I Have Known: Géza Maróczy (1870-1951)". Chesscafe.com.

- Statistics at ChessWorld.net

- Géza Maróczy player profile and games at Chessgames.com

|