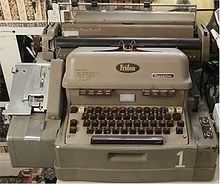

Friden Flexowriter

The Friden Flexowriter was a teleprinter, a heavy duty electric typewriter capable of being driven not only by a human typing, but also automatically by several methods, including direct attachment to a computer and by use of paper tape.

Elements of the design date to the 1920s, and variants of the machine were produced until the early 1970s; the machines found a variety of uses during the evolution of office equipment in the 20th century, including being among the first electric typewriters, computer input and output devices, forerunners of modern word processing, and also having roles in the machine tool and printing industries.

History

Origins and early history

The Flexowriter can trace its roots to some of the earliest electric typewriters. In 1925, the Remington Typewriter Company wanted to expand their offerings to include electric typewriters. Having little expertise or manufacturing ability with electrical appliances, they partnered with Northeast Electric Company of Rochester and made a production run of 2500 electric typewriters. When the time came to make more units, Remington was suffering a management vacuum and could not complete contract negotiations, so Northeast began work on their own electric typewriter. In 1929, they started selling the Electromatic.

In 1931, Northeast was bought by Delco. Delco had no interest in a typewriter product line, so they spun the product off as a separate company called Electromatic. Around this time, Electromatic built a prototype automatic typewriter. This device used a wide roll of paper, similar to a player piano roll. For each key on the typewriter, there was a column on the roll of paper. If the key was to be pressed, then a hole was punched in the column for that key.

In 1932, a code for the paper tape used to drive Linotype and other typesetting machines was standardized. This allowed use of a tape only five to seven holes wide to drive automatic typewriters, teleprinters and similar equipment.

In 1933, IBM wanted to enter the electric typewriter market, and purchased the Electromatic Corporation, renaming the typewriter the IBM Model 01. Versions capable of taking advantage of the paper tape standards were produced, essentially completing the basis of the Flexowriter design.

By the late 1930s, IBM had a nearly complete monopoly on unit record equipment and related punched card machinery, and antitrust issues became a concern as product lines expanded into paper tape and automatic typewriters. As a result, IBM sold the product line and factory to the Commercial Controls Corporation (CCC) of Rochester, New York, which also absorbed the National Postal Meter Corporation. CCC was formed by several former IBM employees.[citation needed]

World War II

Around the time of World War II, CCC developed a proportional spacing model of the Flexowriter known as The Presidential (or sometimes the President). The model name was derived from the fact that these units were used to generate the White House letters informing families of the deaths of service personnel in the war. CCC also manufactured other complex mechanical devices for the war effort, including M1 carbines.

In 1944, the pioneering Harvard Mark I computer was constructed, using an Electromatic for output.

Postwar

After the war, especially in the early 1950s as the computer industry started in earnest, the number of applications for Flexowriters exploded, covering territory in commercial printing, machine tools, computers, and many forms of office automation. This versatility was helped by Friden's willingness to engineer and build many different configurations. In the late 1950s, CCC was purchased by Friden, a maker of electromechanical calculators, and it was under their name that the machines achieved their greatest diversity and success; applications are further detailed below.

End of product line

Friden was acquired by the Singer Corporation in 1965. Singer had little or no understanding of the computer industry, and there was a clash of corporate culture with Friden employees.

Sales and innovation declined. The market for word processing equipment was shifting to magnetic media, such as IBM’s revolutionary Magnetic Tape Selectric Typewriter (MTST), and punched paper tape based solutions were no longer able to compete. The CNC machine tool industry headed the same way. The computer console market consolidated, and the larger manufacturers, such as IBM and DEC, made their own console equipment. Video terminals began to appear as well, beginning to displace paper-based systems there.

Also, Edward Blodgett, Chief Engineer of Friden R&D was replaced in 1964 while ill. It's unclear what effect this had on development, especially as Blodgett was apparently biased against electronics, favoring electromechnical solutions to design problems.

There was a major redesign of the Flexowriter in the late 1960s, adding a plastic case and some electronic interface and control logic and a few indicator lamps. This was the first major change in appearance of the units in nearly forty years. The first edition of British publication Computer Weekly (Thursday, 22 September 1966) carried an article on the front cover featuring the new design, the Friden 2300 Flexowriter, and noted that it sold for £1400 (in British pounds). This would be the last hurrah for the line, with production halting in the early 1970s.

Applications

Automatic typewriters

From its earliest days through to at least the mid-1960s, Flexowriters were used as automatic letter writers.[1]

While the US White House was using them during the Second World War, in the 1960s, United States Members of Congress used Flexowriters extensively to handle enormous volumes of routine correspondence with constituents; an advantage of this method was that these letters appeared to have been individually typed by hand. These were complemented by machines which could use a pen to place a signature on letters making them appear to have been hand-signed.

Auxiliary paper-tape readers could be attached to a Flexowriter to create an early form of "mail merge", where a long custom-created tape containing individual addresses and salutations was merged with a closed-loop form-letter and printed on continuous-form letterhead; both tapes contained embedded "control characters" to switch between readers.

Console terminals

As the unit record equipment (tabulating machine) industry matured and became the computer industry, Flexowriters were commonly used as console terminals for computers. Because ASCII had not yet been standardized, each type of computer tended to use its own system for encoding characters; Flexowriters were capable of being configured with numerous encodings particular to the computer the machine was being used with.

Computers that used Flexowriters as consoles include:

- The Electromatic on the Harvard Mark I

- The MIT Whirlwind I computer, first designed to control a flight simulator, and later becoming the basis of the SAGE network. The Whirlwind lab was later subsumed into the MIT Lincoln Laboratory.

- The Lincoln Laboratory TX-0, an early experimental transistor-based minicomputer, which was to be a seminal influence on hacker culture at MIT in the late 1950s prior to the introduction of the PDP-1.

- The BMEWS DIP computer, NORAD Combat Operations Center (COC), Colorado Springs, Colo., beginning in 1960. (This was before the COC went under Cheyenne Mountain.) Tape code was essentially base-32.

- The Control Data Corporation CDC 160[citation needed]

- Electrodata 205. Electrodata was purchased by the Burroughs Corporation, and many later Burroughs machines also used Flexowriters

- The Librascope LGP-30 and LGP-21

- The Packard Bell PB 250

- The SEA CAB 500

- The ALWAC III-E

Offline punch and printer

Flexowriters could also be used as offline punches and printers. Programmers would type their programs on Flexowriters, which would punch the program onto paper tape. The tapes could then be loaded into computers to run the programs. Computers could then use their own punches to make paper tapes that could be used by the Flexowriters to print output. Among the computers which commonly used Flexowriters for this task were the DEC PDP-1's.

Machine tools

The ability to support diverse encodings meant that adapting Flexowriters to generate the paper tapes used to drive CNC machine tool equipment was a relatively simple affair, and many Flexowriters found homes in machine shops into the 1970s, when magnetic media displaced paper tape in the industry.

Unit record and early computing

Friden manufactured equipment which could connect their calculators to Flexowriters, printing output and performing unit record tasks such as form letters for bills, and eventually manufactured their own computers to further enhance these capabilities. These variants were sold as the Friden Computyper. Computypers were electromechanical; they had no electronics, at least in their earlier models. The calculator mechanism, inside a desk-like enclosure, was much like a Friden model STW desktop calculator, except that it had electrical input (via solenoids) and output (low-torque rotary switches on the dial shafts).

Commercial printing

A product known as the Justowriter (or Just-O-Writer) was developed for the printing industry. It allowed typists to produce justified text for use in typesetting. This worked by having the user type the document on a Recording unit, which placed extra codes for spacing on the paper tape. The tape was placed into a second specially adapted Flexowriter which had two paper tape reading heads; one would read the text while the other controlled the spacing of the print. Spacing codes were stored in relays inside the machine as a line of text progressed. At least some Justowriters used carbon (as opposed to ink-impregnated fabric) ribbons to produce cleaner type, suitable for mass photo-set reproduction.

The Line Casting Control or LCC product generated paper tapes for Linotype and Intertype automatic typesetters. In addition to punching a tape containing the text to be typeset, it turned on a lamp easily seen by the operator to show that the text on the line being typed could be typeset—it was within justifiable range. The LCC had a four-wheel rotary escapement, and a set of gears between the carriage rack and the escapement, to permit the smallest unit of spacing at the escapement to be quite small at the carriage. The spring-tensioned tape that moved the carriage had far more tension (possibly 20 lbs?) than did a standard Flexowriter.

American Type Founders produced a phototypesetter based on the Justowriter/Flexowriter platform.

Finance

There was an "accounting" model with an ultra-wide carriage and two-color ribbon for printing out wide financial reports. The Friden accounting model was called "5010 COMPUTYPER" and was capable of arithmetic functions (addition, subtraction, multiplication & division) at electronic speeds and to print the results automatically in a useful document.

Hardware

As a cutting edge device of their time, Flexowriters, especially some of the specialized types like typesetters, were quite costly. They were made with extreme durability. There were porous bronze bearings, many hardened steel parts, very strong springs, and a substantial AC motor to move all the parts. Most parts are made of heavy gauge steel. The housing and most removable covers were die castings. While the final Singer models did make some use of plastics, even they are quite heavy compared to other electric typewriters of their time. As a result the platen carriage is very heavy, and when the "Carriage return" key is pressed, the carriage moves with about 20 pounds of force and enough momentum to injure a careless operator. If used only as manual typewriters, and properly maintained, Flexowriters might last a century. When reproducing form letters from punched tape, the enormous energy input to the device made watching it a somewhat frightening experience. It also produced enormous noise.

Towards the bottom of the unit there is a large rubber roller ("power roll") that rotates continuously at a few hundred rpm. It provides power for typing as well as power-operated backspace, type basket shift, and power for engaging (and probably disengaging) the carriage return clutch.

Referring to the photo of the cam assembly (often simply called a cam; it was not meant to be disassembled), the holes in the side plates at the lower left are for the assembly's pivot rod, which is fixed to the frame. At the extreme upper left is part of a disconnectable pivot that pulls down on the typing linkage. When installed, down is to the right in the photo, so to speak.

Referring again to the part at the upper left, the mating part has a threaded mounting for adjusting cam clearance from the power roll. The irregular "roundish" part, lower right center, is the cam, itself. It rotates in the frame while in contact with the power roll. The surface of the cam in contact with the power roll had grooves for better grip. As the radius at the contact patch increases, the frame rotates clockwise to pull down on the linkage to type the character.

This particular cam assembly has a cam that rotates a full turn for each operation; it might operate the backspace, basket shift, or carriage-return clutch disengage mechanism. Cams for typing characters rotated only half a turn, the halves of course being identical.

Below the cam in this photo (hidden) is a spring-loaded lever that pushes against a pin on the cam. On the upper edge of the cam, as shown, is a little projection that engages the release lever, which is at the lowest part of the image; it's an irregular shape.

When a key is pressed down, it moves the release lever and unlatches the cam for that letter; the spring-loaded lever pressing on the pin rotates the cam until it engages the power roll. As the cam continues to turn, increasing radius rotates the cam's frame slightly (clockwise in the photo) to operate the typing linkage for that character.

As the cam continues to rotate, the spring-loaded lever pushes on the pin to move it toward home position, but if the key is still down, the cam (now out of contact with the power roll) stalls because the projection on the cam catches on another part of the release lever. The cam stalls until the key is released. When released, the lever catches the projection so the cam is now in home position. This is like a simple clock escapement, and prevents repeated typing. (The "key-down" anti-repeat stop can be removed, so that fast repetitive typing can be done, but this change is difficult to undo.)

Carriage return was done by a non-stretch very durable textile tape attached to the platen advance mechanism at the left of the carriage. For a return, the tape wound up on a small reel operated from the drive system through a clutch. A cam engaged the clutch; it was disengaged by the left margin stop, perhaps directly, perhaps via another cam. (Info. needed here!) A light-torque spring kept the return tape wound on the reel.

The basic mechanism looks just like an IBM electric typewriter from the late 1940s. In fact, some Flexowriter parts are identical in fit and function to the early IBM electric typewriters (those with rotary carriage escapements, a gear-driven power roll, and a governor-controlled variable speed "universal" (wound-rotor/commutator) motor.)

The early IBM rotary-escapement proportional-spacing typewriters (three wheel rotary escapement, spur gear differentials) had code bars to control the amount of carriage movement for the current character. They were operated by the cams. However, the Flexowriter's mechanical encoder was a very different and far more rugged design, although still operated by the cams.

Flexowriters (at least those prior to 1969) do not have transistors; electrical control operations were done with telephone-style (E-Class) relays, and troubleshooting often involved problems with the timing on the relays. Another reader has also found that the timing settings of the various leaf switches (such as in the tape reader) are also important.

The screws used in the Flexowriter were unique, having large flat heads with a very narrow screwdriver slot and a unique thread size and pitch. This may have been a conscious decision. Another reader found that standard 4-40UNC threads appear to fit some of the cover-attachments; internally, the headless set-screws require fluted Bristol keys, which are not commonly available in Great Britain.

There is a holder for a large roll of paper tape on the back of the unit, with tape feeding around to a punch on the left side, toward the rear. The tape reader is on the same side, toward the front, and is essentially identical to the reader shown on the front of the square housing in the photo of the auxiliary reader. The right side of a Flexowriter has a large (~1") connector for hooking the unit up to computers and other equipment. Depending on the model, this connector may be wired in many different ways.

At various times and in various configurations, flexos came with 5, 6, 7 or 8 channel paper tape reader/punches, could have several auxiliary paper tape units attached, and could also attach to IBM punched card equipment.

Flexowriters today

There is (as of 2005) an Electromatic on display at the Smithsonian Institution and (as of late 2006) a Flexowriter at the Boston Museum of Science, in the gallery overlooking the large Van de Graaff generator. In Great Britain, in a private residence in North London, a Model 1 SPD (Systems Programatic Double-case) has been kept operational from 1978 to the present day (2008) and its owner welcomes E-mails to cgmm2@btinternet.com [citation needed]. There are further Flexowriters at the computer museums of the University of Amsterdam and the University of Stuttgart. The French computer museum (Musée de l'Informatique) owns two FlexoWriter which have been used by SEA CAB 500. Two examples, a wide carriage SPD and a president with Auxillary reader on pedestal, are on display at the computermuseum of hackerspace hack.nl near Arnhem, the Netherlands and are frequently demonstrated to astouned spectators.

See also

References

- ↑ O'Kane, Lawrence (1966): "Computer a Help to 'Friendly Doc'; Automated Letter Writer Can Dispense a Cheery Word". The New York Times, May 22, 1966, p. 348: "Automated cordiality will be one of the services offered to physicians and dentists who take space in a new medical center.... The typist will insert the homey touch in the appropriate place as the Friden automated, programmed "Flexowriter" rattles off the form letters requesting payment... or informing that the X-ray's of the patient (kidney) (arm) (stomach) (chest) came out negative."

External links

- Friden Flexowriter: a part of Manuals at bitsavers.org

- Photos and history Retrieved April 10, 2007

- Discussion of Flexowriter code conversion with link to code chart

- Flexowriter patent

- Firearms code markings, including note of CCC produced M-1s.

- Description of Justowriter Also discusses Blodgett

- Video of a Flexowriter SPD typing from a punched tape

- Computer museum @ hack42.nl