Fred Kabotie

| Fred Kabotie | |

|---|---|

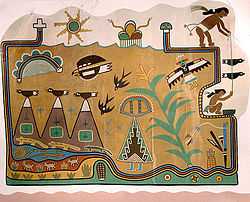

Fred Kabotie mural at Painted Desert Inn, c. 1947 | |

| Birth name | Nawavoy'ma |

| Born |

c. 1900 Shongopovi, Arizona, USA |

| Died | February 28, 1986 |

| Nationality | Hopi |

| Field | Painting, silversmithing |

| Training | Self-taught |

| Movement | Traditional |

| Patrons | Museum of Modern Art, Elizabeth DeHuff, The George Gustav Heye Center |

| Awards | Guggenheim Fellowship |

Fred Kabotie (c. 1900–1986) was a celebrated Hopi painter, silversmith, and educator.

Background and education

Fred Kabotie was born into a highly traditional Hopi family at Songo`opavi, Second Mesa, Arizona, Kabotie. His father belonged to the sun clan and he belonged to the Bluebird Clan. His Hopi name was Naqavo'ma, meaning "the sun coming up day after day"; however, his paternal grandfather gave him the nickname Qaavotay, meaning "tomorrow."[1] His teacher at Toreva Day School spelled his nickname "Kabotie," which stuck with him for the rest of his life.[2]

As a child, he drew images of katsinas with bits of coal and earth pigments onto rock surfaces near his home.[1]

After his spotty attendance at the local day school, Kabotie was forced to attend the Santa Fe Indian School, where he says, "I was supposed to discard all my Hopi belief, all my Hopi way of life, and become a white man and become a Christian." English was the only language students were allowed to speak. John DeHuff became superintendent of the school and went against the prevailing government policy of suppressing Native cultures. Elizabeth DeHuff, John's wife, taught painting to students from the school, beginning with Kabotie. Missing his home, Kabotie painted katsinas and sold his first painting for 50 cents to the school's carpentry teacher.[2]

Because of his encouragement of Native cultures, John DeHuff was demoted from his post and forced to leave the school. He convinced Kabotie to continue his education at Santa Fe Public High School. During his summer vacations, Kabotie worked with artists Velino Shije Herrera (Zia Pueblo) and Alfonso Roybal (San Ildefonso Pueblo) on archaeological excavations for the Museum of New Mexico[3] Kabotie commenced a long association with Edgar Lee Hewett, a local archaeologist, working at such excavations as Jemez Springs, New Mexico and Gran Quivira.

Early career and personal life

After graduation in the 1920s, the Museum of New Mexico hired Kabotie to paint and bind books for a salary of $60 per month. Elizabeth DeHuff hired him to illustrate books. The George Gustav Heye Center in New York City commissioned a series of paintings depicting Hopi ceremonies, and he sold works to private collectors. He primarily painted with watercolor on paper.[3]

In 1930, Kabotie moved back to Shungopavi, where he lived for most of his life. He was initiated into the Wuwtsimt men's society and married Alice Talayaonema.[3]

Mary Colter commissioned him to paint murals in her Desert View Watchtower in 1933. In 1937, a high school opened for Hopi students and Kabotie taught painting there for 22 years (1937–1959). He taught hundreds of Hopi students and some went on to have successful art careers of their own. He was an advisor at the 1939 Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco, where he curated a show of Native American art.[3]

In 1940, he was commissioned to reproduce the prehistoric murals at Awatovi Ruins at the Museum of Modern Art.[4] He won the Guggenheim Fellowship in 1945, which enabled him to study Mimbres pottery and write the book, Designs From the Ancient Mimbreños.[3]

Silverwork

The Museum of Northern Arizona encouraged Kabotie and his cousin Paul Saufkie (1898–1993) to develop a jewelry style unique to Hopi people.[5] They developed an overlay technique, distinct from Zuni and Navajo silversmithing. They created designs inspired by traditional Hopi pottery.[3] A friend and benefactor, Leslie Van Ness Denman commissioned Kabotie's first piece of jewelry as a gift to Eleanor Roosevelt.[6]

The Indian Service and GI Bill funded jewelry classes at the museum for returning Hopi veterans of World War II. Kabotie taught design and Saufkie taught technique. To showcase their students' work, they created the Hopi Silvercraft Cooperative Guild in 1949, which has a shop on Second Mesa today.[5][7]

Later career

With his wife, Kabotie represented the US Department of Agriculture at the World Agricultural Fair in New Delhi, India in 1960. The high school at Hopi closed, so upon his return from India, Kabotie worked with the Indian Arts and Crafts Board.[7] His many pursuits left him little time to paint after the 1950s.[8]

He had long assisted other tribal members in marketing their artwork and a lifelong dream was realized with the founding of the Hopi Cultural Center. Kabotie was elected as president of the board in 1965, and in 1971 the Center was officially dedicated.[7]

In 1977, the Museum of Northern Arizona published his biography,[7] Fred Kabotie: Hopi Indian Artist, co-authored Bill Belknap.[9]

Death and legacy

Kabotie died on February 28, 1986 after a long illness. "The Hopi believe that when you pass away," he said, "your breath, your soul, becomes into the natural life, into the powers of the deity. Then you will become mingled with all this nature again, such as clouds... That way you will come back to your people..."[8]

He was best known for his painting, and he is estimated to have finished 500 paintings.[7] Fred's son Michael Kabotie (1942–2009) was also a well-known artist.

Published works

- Kabotie, Fred. Designs from the Ancient Mimbreños With Hopi Interpretation. Flagstaff, AZ: Northland Publishing, 1982. Second Edition. ISBN 978-0-87358-308-4.

See also

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Seymour, 242

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Seymour, 243

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Seymour, 244

- ↑ Kabotie biography

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Contemporary Artists: Hopi." American Museum of Natural History. (retrieved 16 February 2010)

- ↑ Seymour, 244-5

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Seymour, 245

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Seymour, 246

- ↑ Fred Kabotie: Hopi Indian Artist. Amazon.com (retrieved 16 February 2010)

References

- Seymour, Tryntje Van Ness. When the Rainbow Touches Down. Phoenix, AZ: Heard Museum, 1988. ISBN 0-934351-01-5.

- Welton, Jessica. The Watchtower Murals. Plateau (Museum of Northern Arizona), Fall/Winter 2005. ISBN 0-89734-132-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fred Kabotie. |

- Historic photos of Watchtower murals

- Fred Kabotie portrait, c. 1932, photo by Mary Colter

- Hide painting by Fred Kabotie

|