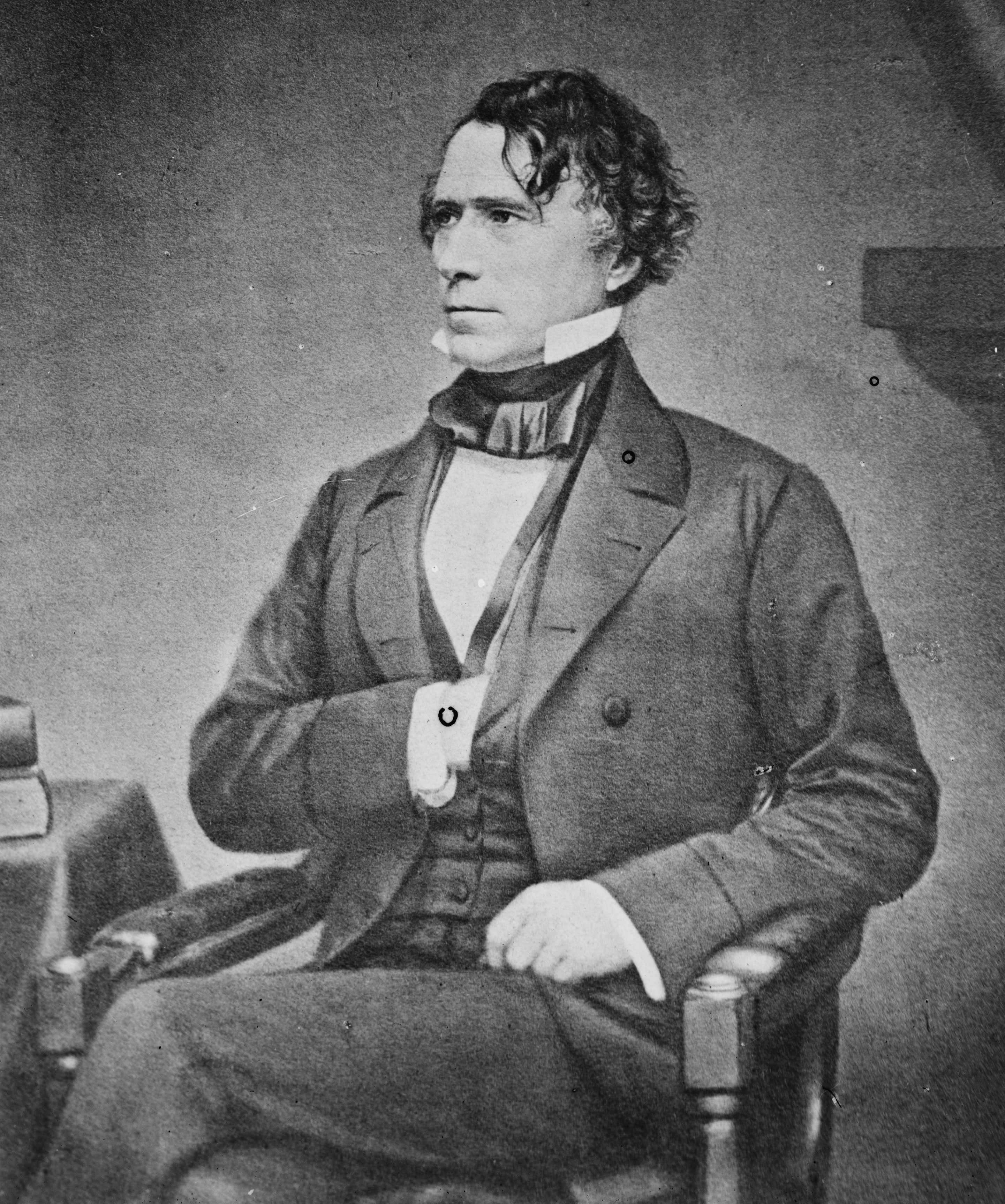

Franklin Pierce

| Franklin Pierce | |

|---|---|

| |

| 14th President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1853 – March 4, 1857 | |

| Vice President | William R. King (1853) None (1853–1857) |

| Preceded by | Millard Fillmore |

| Succeeded by | James Buchanan |

| United States Senator from New Hampshire | |

| In office March 4, 1837 – February 28, 1842 | |

| Preceded by | John Page |

| Succeeded by | Leonard Wilcox |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from New Hampshire's At-large district | |

| In office March 4, 1833 – March 4, 1837 | |

| Preceded by | Joseph Hammons |

| Succeeded by | Jared Williams |

| Personal details | |

| Born | November 23, 1804 Hillsborough, New Hampshire |

| Died | October 8, 1869 (aged 64) Concord, New Hampshire |

| Resting place | Old North Cemetery Concord, New Hampshire |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Jane Appleton (1834–1863; her death) |

| Children | Franklin Frank Robert Benjamin |

| Alma mater | Bowdoin College |

| Profession | Lawyer |

| Religion | Episcopal |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Service/branch | U.S. Army |

| Years of service | 1847 – 1848 |

| Rank | Brigadier General |

| Battles/wars | Mexican–American War • Battle of Contreras • Battle of Churubusco • Battle of Molino del Rey • Battle of Chapultepec • Battle for Mexico City |

Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804 – October 8, 1869) was the 14th President of the United States (1853–1857) and is the only President from New Hampshire. Pierce was a Democrat and a "doughface" (a Northerner with Southern sympathies)[1] who served in the U.S. House of Representatives and the Senate. Pierce took part in the Mexican–American War and became a brigadier general in the Army. His private law practice in his home state was so successful that he was offered several important positions, which he turned down. Later, he was nominated as the party's candidate for president on the 49th ballot at the 1852 Democratic National Convention.[2] In the presidential election, Pierce and his running mate William R. King won by a landslide in the Electoral College. They defeated the Whig Party ticket of Winfield Scott and William A. Graham by a 50 percent to 44 percent margin in the popular vote and 254 to 42 in the electoral vote.

He made many friends, but he suffered tragedy in his personal life; all of his children died young. As president, he made many divisive decisions which were widely criticized and earned him a reputation as one of the worst presidents in U.S. history. Pierce's popularity in the Northern states declined sharply after he supported the Kansas–Nebraska Act, which replaced the Missouri Compromise and renewed debate over the expansion of slavery in the American West. Pierce's credibility was further damaged when several of his diplomats issued the Ostend Manifesto. The historian David Potter concludes that the Ostend Manifesto and the Kansas–Nebraska Act were "the two great calamities of the Franklin Pierce administration.... Both brought down an avalanche of public criticism."[3] More importantly, says Potter, they permanently discredited Manifest Destiny and "popular sovereignty" as political doctrines.

Despite a reputation as an able politician and a likable man, during Pierce's presidency he served only as a moderator among the increasingly bitter factions that were driving the nation towards civil war.[4] Abandoned by his party, Pierce was not renominated to run in the 1856 presidential election. His reputation was destroyed during the Civil War when he declared support for the Confederacy, and personal correspondence between Pierce and the Confederate President Jefferson Davis was leaked to the press.

Philip B. Kunhardt and Peter W. Kunhardt reflected the views of many historians when they wrote in The American President that Pierce was

"a good man who didn't understand his own shortcomings. He was genuinely religious, he loved his wife, and he reshaped himself so that he could adapt to her ways and show her true affection. He was one of the most popular men in New Hampshire, polite and thoughtful, easy, and good at the political game, charming and fine and handsome. However, he has been criticized as timid and unable to cope with a changing America."[5]

Early life and education

Franklin Pierce was born in a log cabin in Hillsborough, in the northeastern state of New Hampshire, on November 23, 1804. He was a sixth-generation descendant of Thomas Pierce, who had moved to the Massachusetts Bay Colony from Shropshire, England, in the 1630s. Pierce's father Benjamin was then a prominent New Hampshire state legislator, farmer, and tavern-keeper. A lieutenant in the Revolutionary War, Benjamin moved from Chelmsford, Massachusetts to Hillsborough after the war, purchasing fifty acres of land. Franklin Pierce was the fifth of eight children born to Benjamin and his second wife, Anna Kendrick (his first wife Elizabeth Andrews died in childbirth, leaving a daughter). During Pierce's childhood his father would serve as a governor's councilman and county sheriff in the Republican Party, while two of his older brothers fought in the War of 1812; politics and republicanism were thus a major influence in his early life.[6]

Pierce's father, who sought to ensure that his sons were educated, placed Pierce in a brick schoolhouse at Hillsborough Center in childhood and sent him to Hancock Academy at the age of 12. The boy was not fond of schooling and grew homesick at Hancock. According to a popular anecdote he walked twelve miles back to his home one Sunday; his father fed him dinner and drove him part of the distance back to school before kicking him out of the carriage and ordering him to walk the rest of the way in a thunderstorm. Pierce learned from the experience, later citing this moment as "the turning-point in my life". Later that year he transferred to Phillips Exeter Academy to prepare for college. By this time he had built a reputation as a charming but rambunctious student.[7]

In fall 1820, Pierce entered Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine, one of nineteen freshmen. He joined the Athenian Society, a progressive literary society and rival to the school's older group, the Peucinians. The two societies were the center of social life at Bowdoin, and Pierce was joined by fellow Athenians Jonathan Cilley (later elected to Congress) and Nathaniel Hawthorne (now a literary icon), with whom he formed lasting friendships. Among Pierce's other noteworthy classmates was author Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, although the two were not especially close. In his second year of college, Pierce had the second lowest grades in his class, but he worked to improve them; he ranked third among his classmates when he graduated in 1824.[8] After briefly studying with former New Hampshire Governor Levi Woodbury, a family friend, he spent a semester at Northampton Law School in Northampton, Massachusetts, followed by a period of study under Judge Edmund Parker in Amherst, New Hampshire. He was admitted to the bar in the fall of 1827 and began work on a practice in Hillsborough.[9]

Life in New Hampshire

State politics

With his father climbing the ranks of New Hampshire politics, Pierce was never far from a political discussion, speech, or campaign. By 1824 the state was a hotbed of partisanship, with figures such as Woodbury and Isaac Hill laying the groundwork for a party of "democrats" in support of General Andrew Jackson. They opposed the established Federalists (and their successors, the National Republicans), who were led by sitting President John Quincy Adams. The work of the New Hampshire Democratic Party came to fruition in March 1827 when their pro-Jackson nominee, Benjamin Pierce, won the support of the pro-Adams faction and was elected governor of New Hampshire essentially unopposed. While the younger Pierce had set out to build a career as an attorney, he was fully drawn into the realm of politics as the 1828 presidential election between Adams and Jackson approached. In the state elections held in March 1828, the Adams crowd withdrew their support of Benjamin Pierce, voting him out of office,[note 1] but Franklin Pierce won his first election: Hillsborough town moderator, a position to which he would be elected for six consecutive years.[10]

That year Pierce actively campaigned in his district on behalf of Jackson, who carried both the district and the nation by a large margin in the November election. The election further strengthened the Democratic Party, and Pierce won his first legislative seat the following year, representing Hillsborough in the New Hampshire House of Representatives (Pierce's father, meanwhile, won a second term as governor, his last before retiring.) He was made chairman of the House Education Committee and re-elected the following year. By 1831 the Democrats held a legislative majority and Pierce was elected speaker of the House. The young speaker used his platform to oppose the expansion of banking, protect the state militia, and to offer support to the national Democrats and Jackson's re-election effort. At the age of 27 he was a star of the New Hampshire Democratic Party, although his personal life was nowhere near as successful—in his personal letters he continued to lament his bachelorhood and yearned to find a life beyond Hillsborough.[11]

Pierce was appointed aide de camp to Governor Samuel Dinsmoor in 1831. He remained in the state militia until 1847 and attained the rank of Colonel before becoming a Brigadier General in the Army during the Mexican–American War.[12][13]

In late 1832, the Democratic Party convention nominated Pierce for one of New Hampshire's five seats in the U.S. House of Representatives. This was tantamount to election for the young Democrat, as the Federalist Party had become nearly powerless in the state, further dampened by Jackson's re-election that year. Pierce won the March 1833 election to Congress unopposed, but he would not take office until the end of the year, and his attention was elsewhere. He had recently become engaged to Jane Means Appleton, and bought his first house in Hillsborough. He maintained some distance from the state legislature throughout the year, while finishing his final term as speaker.[14]

Marriage and family

On November 19, 1834, Pierce married Jane Means Appleton (1806–63), the daughter of Jesse Appleton, a former president of Bowdoin College. Jane was Pierce's opposite. Born into an elite Whig family, she was shy, whereas he was very extroverted. Often ill, she was deeply religious and pro-temperance.[15] They lived permanently in Concord, New Hampshire. They had three children, all of whom died in childhood:

- Franklin Pierce, Jr. (February 2, 1836 – February 5, 1836)

- Frank Robert Pierce (August 27, 1839 – November 14, 1843), died at the age of four from epidemic typhus

- Benjamin Pierce (April 13, 1841 – January 6, 1853), died at the age of 11 in a railroad accident.

None of the sons lived to see his father become president.[16] Benjamin's death occurred after his father's election, but before his inauguration.

Congressional career

U.S. House of Representatives

He departed in November 1833 for Washington, D.C., where the Twenty-third United States Congress convened on December 2. With Jackson's second term underway, Congress had a strong Democratic majority, whose primary focus was to prevent the Second Bank of the United States from being rechartered. The Democrats, including Pierce, shot down challenges from the newly formed Whig Party, and the bank was dissolved. Pierce broke from his party on occasion, opposing Democratic bills to fund internal improvements with federal money. He saw both the bank and infrastructure spending as unconstitutional. The Pierces married in November 1834; this period was fairly uneventful from a legislative standpoint, and Pierce was easily re-elected the following March. He returned to Hillsborough with Jane, remodeled his home, and attended to his law practice until the Twenty-fourth Congress convened in December.[17]

As northern abolitionism grew more vocal in the mid-1830s, Congress was inundated with petitions from anti-slavery groups seeking legislative action to restrict slavery in the United States. From the beginning, Pierce found the abolitionists' "agitation" to be an annoyance, and saw federal action against slavery as an infringement on southern states' rights, even though he was morally opposed to slavery itself.[18] "I consider slavery a social and political evil," Pierce said, "and most sincerely wish that it had no existence upon the face of the earth."[19] Still, he wrote in December 1835, "One thing must be perfectly apparent to every intelligent man. This abolition movement must be crushed or there is an end to the Union."[20] He was also frustrated with the "religious bigotry" of abolitionists, who cast their political opponents as sinners.[21]

When Rep. James Henry Hammond of South Carolina looked to prevent anti-slavery petitions from reaching the House floor, however, Pierce sided with the abolitionists' right to petition.[18] In his House speeches he portrayed the abolitionist petitioners as a minority in his state; he said that most of the signatories were women and children—i.e., nonvoters, whose opinions were irrelevant to congressional business. He was attacked by the New Hampshire anti-slavery Herald of Freedom as a "doughface", which had the dual meaning of "craven spirited man" and "northerner with southern sympathies"; he took to the House floor to express his indignation at the insult.[22]

U.S. Senate

The departure in May 1836 of then-Senator Isaac Hill, who had been elected governor of New Hampshire, left a brief interim opening to be filled by the state legislature. Pierce's candidacy for the Senate was championed by Representative John P. Hale, a fellow Athenian from his college days. After a vigorous debate, the legislature chose John Page to fill the rest of Hill's term. In 1837 Pierce was elected to a full six-year term beginning in March 1837, and succeeded Page, becoming the youngest member of the Senate at that time. The election came at a difficult time for Pierce, as his father, sister, and brother were all seriously ill, while Jane continued to suffer from chronic health issues.[23]

Pierce was a reliable party-line vote on most issues in the Senate. He was an able politician, but never an eminent one; he was overshadowed by the Great Triumvirate of Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, and John C. Calhoun who then dominated the Senate.[24] Pierce entered the Senate at a time of worldwide economic crisis, as the Panic of 1837 was underway. He considered the depression a result of the banking system's rapid growth, amidst "the extravagance of overtrading and the wilderness of speculation". He supported newly elected Democratic president Martin Van Buren and his plan to create an independent treasury, a proposal which split the Democratic Party. Debate over slavery continued to roil Congress, and Pierce supported a resolution by John C. Calhoun to preserve slavery in Washington, D.C. In his view, the abolitionists' attempt to ban slavery in the capital was a dangerous stepping stone to nationwide emancipation.[25] Meanwhile, the Whigs were growing in strength against the Democrats, which would leave Pierce's party with only a slight majority by the end of the decade.[26]

One topic of particular importance to Pierce was the military. He challenged a bill which would expand the ranks of the Army's staff officers in Washington without any apparent benefit to line officers at posts in the rest of the country. He took interest in military pensions, seeing abundant fraud within the system, and was named chairman of the Senate Committee on Military Pensions in the Twenty-sixth Congress (1839–1841). As a member of the Committee on Military Affairs, he urged a modernization and expansion of the Army, with a focus on militias and mobility rather than coastal fortifications which he considered outdated.[27]

He campaigned vigorously throughout his home state for Van Buren's re-election in the 1840 presidential election. The incumbent carried New Hampshire but lost the national vote to William Henry Harrison, the Whig military hero, and the Whigs took a majority of seats in the Twenty-seventh Congress. Pierce and the Democrats were quick to challenge the new administration, questioning Harrison's use of the spoils system and protesting the renewed Whig plan for a national bank. While the Democrats were outnumbered, circumstances changed when Harrison died one month into his term, leaving John Tyler as his successor; Tyler's opposition to a national bank crippled the Whigs' efforts. In December 1841 Pierce decided to resign from Congress, something he had been planning for some time.[28] His last acts in the Senate were to oppose a bill distributing federal funds to the states, believing that the money should go to the military instead; and to challenge the Whigs to reveal the results of their investigation of the New York Customs House, where the Whigs had probed for Democratic corruption for nearly a year but issued no findings.[29]

Life after Congress

Pierce had plenty of incentive to leave Washington. Several years earlier he and Jane had moved from Hillsborough to the capital city of Concord, where he would benefit from the abundant legal opportunities in Concord and Jane would enjoy a more robust community life.[30] Jane remained in Concord with her young son Frank and her newborn Benjamin for the latter part of Pierce's Senate term, and this separation was taking a toll on the family. Pierce, meanwhile, had begun a law partnership with Asa Fowler where he practiced during congressional recesses; the practice was an increasingly demanding but lucrative opportunity. All this gave him much to attend to when he returned to Concord.[31] Pierce returned to Concord in early 1842, and his reputation as a lawyer continued to flourish. Known for his gracious personality, eloquence, and excellent memory, Pierce would attract large audiences to hear him deliver an argument in court. He would often represent poor clients for little to no compensation.[32]

Despite Pierce's growing career and family obligations, he was immediately drawn into the political turmoil growing within the state Democratic Party. Governor Hill, who represented the commercial, urban wing of the party, supported the use of government charters to confer special privileges on corporations, such as limited liability and eminent domain for building rail. The radical "locofoco" wing of his party represented farmers and other rural voters, who sought an expansion of social programs and labor regulations and a restriction on corporate privileges. The state's political culture grew less tolerant of banks and corporations in the wake of the Panic of 1837, and Hill was voted out of office. Pierce was closer to the radicals philosophically, and reluctantly served as attorney in a publisher's dispute against Hill, which made tensions worse.[33]

In June 1842 Pierce was named chairman of the State Democratic Committee. In the following year's state election he helped the radical wing take over the state legislature despite Hill's efforts to retain control. The party was split on several issues, including railroad development and the temperance movement, and Pierce took a leading role in helping the state legislature settle their differences. His priorities were "order, moderation, compromise, and party unity", which he tried to place ahead of his personal views on political issues.[34]

The surprise victory of dark horse Democratic candidate James K. Polk in the 1844 presidential election was welcome news to Pierce, who had befriended the former Speaker of the House during his time in Congress. Pierce had campaigned heavily for Polk during the election, and in turn Polk appointed him U.S. Attorney for the District of New Hampshire shortly after taking office.[35] Polk's most prominent cause was the annexation of Texas, an issue which caused a dramatic split between Pierce and his former ally Hale, now a U.S. Representative. Hale was so impassioned against adding a new slave state that he wrote a letter to 1,400 Democrats in New Hampshire outlining his opposition to the measure. Pierce "immediately sprang into action", assembling the state Democratic leadership to oust Hale from the party. What followed was a political firestorm which led to Pierce cutting off ties with his longtime friend, and with his law partner Fowler, who was a Hale supporter.[36]

Mexican–American War

Active military service was a long-held dream for Pierce, who had admired his father's and brothers' service in his youth. As a legislator, he was a passionate advocate for volunteer militias. As a militia officer himself, he had experience mustering and drilling bodies of troops. When President Polk declared war against Mexico in May 1846, Pierce immediately volunteered to join, although no New England regiment yet existed. His hope to fight in the war was one reason he refused an offer to become U.S. Attorney General. As the efforts of Generals Winfield Scott and Zachary Taylor grew more intense, Congress passed a bill authorizing creation of ten regiments, and Pierce was appointed Colonel and commander of the 9th Infantry Regiment in February 1847.[37]

On March 3 he was promoted to Brigadier General. He took command of a brigade of reinforcements for General Scott's army, which at the time was plotting to invade Mexico City via the port of Vera Cruz. Needing time to assemble his brigade, Pierce reached the already-seized port of Vera Cruz in late June, where he prepared a march of 2,500 men along with supplies to catch up with Scott. The three-week journey inland was perilous, and the men fought off several attacks before joining with Scott's army in early August, in time for the Battle of Contreras.[38] The battle was disastrous for Pierce: his horse was suddenly startled during a charge, knocking Pierce groin-first against his saddle. The horse then tripped into a crevice and fell, pinning Pierce underneath and leaving him with a debilitating knee injury.[39]

He returned to his command the following day, but was in grievous pain and spent much of the time resting in back of a wagon. As the Battle of Churubusco approached, he was ordered by Scott to the rear. He responded, "For God's sake, General, this is the last great battle, and I must lead my brigade." Scott yielded, and Pierce entered the fight tied to his saddle, but the pain in his leg became so great that he passed out on the field. The Americans won the battle and Pierce helped negotiate an armistice. He then returned to command and led his brigade throughout the rest of the campaign, eventually taking part in the capture of Mexico City in mid-September, although his brigade was held in reserve for much of the battle. He remained in command during the three-month occupation of the city, while frustrated with the stalling of peace negotiations, and tried to distance himself from the constant conflict between Scott and the other generals.[40]

Pierce was finally allowed to return to Concord in late December 1847. He was given a positive reception in his home state and issued his resignation from the Army, which was approved on March 20, 1848. His military exploits elevated his popularity in Hew Hampshire, but his injuries and subsequent troubles in battle led to accusations of cowardice from his opponents for the rest of his political career. He had demonstrated competence as a general, especially in his initial march from Vera Cruz, but his short tenure and his injury left little for historians to judge his ability as a military commander.[41]

Ulysses S. Grant, who had the opportunity to observe Pierce firsthand during the war, countered the allegations of cowardice in his memoirs, even though by the time Grant wrote Pierce had been dead for several years. Though not an admirer of Pierce's politics, Grant described him this way: "Whatever General Pierce's qualifications may have been for the Presidency, he was a gentleman and a man of courage. I was not a supporter of him politically, but I knew him more intimately than I did any other of the volunteer generals."[42]

Party leadership

Returning to Concord, Pierce resumed his law work; in one notable case he defended the religious liberty of the Shakers, the insular sect who were being threatened with legal action over accusations of abuse. His role as a party leader, however, continued to take up most of his attention. He continued to wrangle with Hale, now a U.S. Senator who was frustrating the party leadership with his vocal left-wing stances, opposing the Mexican war and pushing anti-slavery resolutions that were regarded as needless agitation.[43]

As the 1848 presidential election approached, the party was divided between the abolitionist Van Buren faction (the "Barnburners") and the pro-compromise Polk faction (the "Hunkers"). The abolitionists' Wilmot Proviso, which would ban slavery in any new territorial acquisitions from Mexico, was a particular point of contention. As Whig leader Henry Clay introduced his Compromise of 1850, the Democrats loosely supported it, and Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas led an effort to split the omnibus bill into separate bills so that each legislator could vote against the parts his state opposed without endangering the overall package.

Pierce strongly supported the compromise; in a speech he reiterated how he detested slavery as much as any abolitionist, but regarded dissolution of the "Eternal Union" as an even greater evil. This led him to ally with the northern Whig Daniel Webster even as many New Englanders regarded Webster as a sellout to southern interests. When Pierce learned that his brother Henry, a state legislator, was planning to vote for resolutions condemning the compromise, Pierce fled to a Manchester train station and demanded a train be run off-schedule so he could reach him. He threatened Henry at his hotel: "If you vote for those resolutions ... you are no brother of mine: I will never speak to you again." Henry replied that Pierce was mistaken, as he entirely supported the compromise.[44]

He served as president of the New Hampshire state constitutional convention in November 1850. The convention looked to liberalize the outdated New Hampshire state constitution of 1792, which differed from most other states in several respects. Pierce railed against the constitution's infringements on religious liberty, a principle he held dear. The convention struck the excessive property and religious qualifications for holding office, which the legislature had long stopped enforcing. The number of legislators was slashed and the elections were made less frequent. The convention also sent a resolution favoring the Compromise.[45]

To appease the Free Soilers, the Democrats had nominated the abolitionist Rev. Atwood for governor, which created an awkward rift when Atwood stated his opposition to the Fugitive Slave Act. Pierce pressured him to issue a partial retraction, to endorse the act as part of a compromise if it would protect the Union. Atwood quickly regretted his retraction, which he said was written under duress from Pierce. Pierce denied coercing Atwood into a retraction, and called for a convention to cancel Atwood's nomination: his conflicting opinions had become a confusing liability to the party. The fiasco would compromise the election for the Democrats, who lost several races, and not a single constitutional change was approved by the voters. Still, Pierce's party retained its control over the state, and was well positioned for the upcoming presidential election.[46]

Election of 1852

The Democrats were eager to find their standard-bearer for the 1852 presidential election as early as mid-1851. Yet the party was split by age and geography—most of the "Barnburners" who had left the party with Martin Van Buren to form the Free Soil Party had returned—and it was widely expected that the 1852 Democratic National Convention would result in deadlock, with no candidate winning the necessary two-thirds majority. New Hampshire Democrats attempted with little success to rally for Woodbury as a compromise candidate, but Woodbury's death in September 1851 opened up an opportunity for Pierce's allies to present him as a potential dark horse in the mold of Polk.[47]

Pierce was under the radar, as he had not held elective office in nearly a decade, and lacked the front-runners' national presence. He publicly declared such that a nomination would be "utterly repugnant to my tastes and wishes", but he understood that his position as state party leader was in jeopardy if he flatly refused his allies' ambitions. He quietly allowed his supporters for lobby for him, with the understanding that his name would not be brought up at the convention until it was clear none of the front-runners could break the deadlock. To broaden his potential base of southern voters as the convention approached, he wrote letters clarifying his support for the Compromise of 1850 and the Fugitive Slave Act.[48]

The convention assembled on June 1 in Baltimore, Maryland, and the deadlock went as predicted. Among the major contenders were 1848 Democratic candidate Lewis Cass, James Buchanan, William L. Marcy, and Stephen A. Douglas. The first ballot was taken on the third day of the convention. Of 288 delegates Cass claimed 116, Buchanan 93, and the rest were split, without a single vote for Pierce. 34 ballots passed with little progress. The Buchanan team decided to have their delegates experiment with combinations of minor candidates in order to attract these minor candidates' supporters and demonstrate Buchanan as a clear second choice. This novel tactic backfired after several ballots as Virginia, New Hampshire, and Maine switched to Pierce, the remaining Buchanan forces began to break for Marcy, and before long Pierce was in third place. After the 48th ballot, North Carolina congressman James C. Dobbin delivered an unexpected and passionate endorsement of Pierce, sparking a wave of support for the dark horse candidate. In the 49th ballot, Pierce received all but 6 of the votes. Delegates selected Alabama Senator William R. King as his running mate, and adopted a party platform that rejected further "agitation" over the slavery issue and supported the Compromise of 1850.[49]

The Whig candidate was General Winfield Scott of Virginia, under whom Pierce had served in the Mexican–American War; his running mate was Secretary of the Navy William A. Graham. The Whigs could not unify their factions as the Democrats had, and the convention adopted a platform almost indistinguishable from that of the Democrats, including support of the Compromise of 1850. This incited the Free Soilers to field their own candidate, at the expense of the Whigs. The lack of political differences reduced the campaign to a bitter personality contest and helped to drive voter turnout in the election to its lowest level since 1836; it was "one of the least exciting campaigns in presidential history".[50]

Pierce kept quiet during the campaign so as not to upset his party's delicate unity, and allowed his allies to run the campaign.[51] Pierce's opponents caricatured him as a fainting, cowardly war leader, an alcoholic ("the hero of many a well-fought bottle"), and an anti-Catholic.[52] Scott, meanwhile, drew weak support from the Whigs, who were torn by his pro-Compromise platform and found him to be an abysmal, gaffe-prone public speaker.[53] The Democrats were confident: a popular slogan was that the Democrats "will pierce their enemies in 1852 as they poked them in 1844," a reference to the victory of James K. Polk in the 1844 election.[54] This proved to be true, as Scott won only the states of Kentucky, Tennessee, Massachusetts, and Vermont, finishing with 42 electoral votes to Pierce's 254. With 3.2 million votes cast, Pierce won the popular vote with 50.9 to 44.1 percent. A sizable block of Free Soilers broke for John P. Hale, who won 4.9 percent of the popular vote.[55]

On January 6, 1853, weeks after his election as president, the Pierces and their last son Benjamin were in a train accident. The boy was nearly decapitated. Pierce covered him with a sheet, hoping to spare his wife, but Jane also saw their son. They both suffered severe depression afterward, which affected Pierce's performance throughout his presidency.[56]

Presidency 1853–1857

Beginnings

Pierce served as President from March 4, 1853, to March 4, 1857. He began his presidency in mourning. Two months before, on January 6, 1853, the President-elect's family had been trapped in a train from Boston when their car derailed and rolled down an embankment near Andover, Massachusetts. Pierce and his wife survived but saw their last son, 11-year-old Benjamin, crushed to death.[57][58] Jane Pierce viewed the train accident as a divine punishment for her husband's pursuit and acceptance of high office.[59]

As the first president elected to be born in the 19th century, Pierce chose to affirm his oath of office rather than swear it, becoming the first president to do so; he placed his hand on a law book rather than on a Bible. He was the first president to recite his inaugural address from memory. Pierce hailed an era of peace and prosperity at home and urged a vigorous assertion of US interests in its foreign relations. "The policy of my Administration", said the new president,

- "will not be deterred by any timid forebodings of evil from expansion. Indeed, it is not to be disguised that our attitude as a nation and our position on the globe render the acquisition of certain possessions not within our jurisdiction eminently important for our protection".[60]

The nation was enjoying economic growth and relative tranquility, and the Compromise of 1850 calmed the debate over slavery. When the issue flamed up early in his administration, Pierce did little to cool the passions it aroused. Sectional conflicts reignited.[61] In the first year of his presidency, he was arrested for running over an old woman with his horse, but charges were dropped due to a lack of sufficient evidence.[62]

Administration

Pierce selected men of differing opinions for his Cabinet, including colleagues he knew personally and Democratic politicians. Many anticipated the diverse group would soon break up, but it remained unchanged during Pierce's four-year term (as of 2013, the only presidential cabinet to do so). In foreign policy, Pierce sought to display a traditional Democratic assertiveness. Various interests nursed ambitions to detach nearby Cuba from a weak and distant Spain, open trade with a reclusive Japan, and gain the advantage over Britain in Central America. Although the Perry Expedition to Japan was a success, Pierce's leadership increasingly came into question when poorly anticipated developments exposed failures of Administration planning and consultation.[63]

Pierce's administration aroused sectional apprehensions when it pressured the United Kingdom to relinquish its interests along part of the Central American coast. Three US diplomats in Europe drafted a proposal to the president to purchase Cuba from Spain for $120 million (USD), and justify the "wresting" of it from Spain if the offer were refused. The publication of the Ostend Manifesto, which had been drawn up on the insistence of Pierce's Secretary of State, provoked the scorn of Northerners who viewed it as an attempt to annex a slave-holding possession to bolster Southern interests. It helped discredit the expansionist policies the Democratic Party had supported in the 1844 election. The Gadsden Purchase from Mexico similarly exposed the seething unresolved sectional conflicts inherent in national expansion.

An 1856 cartoon depicts a giant free soiler being held down by James Buchanan and Lewis Cass standing on the Democratic platform marked "Kansas", "Cuba", and "Central America". President Pierce also holds down the giant's beard as Stephen A. Douglas shoves a black man down his throat.

The greatest challenge to the country's equilibrium during the Pierce administration, though, was the passage of the Kansas–Nebraska Act in 1854. It repealed the Missouri Compromise and reopened the question of slavery in the West. This measure, sponsored by Senator Stephen A. Douglas, originated in a drive to promote a transcontinental railroad with a link from Chicago, Illinois, to California through Nebraska.

Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, advocate of a southern transcontinental route, had persuaded Pierce to send James Gadsden to Mexico to buy land for a southern railroad. He purchased the area now comprising southern Arizona and part of southern New Mexico for $10 million (USD), commonly known as the Gadsden Purchase.[64] This became known as the greatest success of the Pierce presidency. Under Pierce's watch, Commodore Matthew C. Perry concluded a treaty with Japan allowing American trade with that country.[65]

Pierce fulfilled the expectations of Southerners who had supported him by vigilantly enforcing the Fugitive Slave Act when Anthony Burns was seized in Boston in 1854. Federal troops enforced the return to his owner against angry crowds.[66]

Organizing the territories of Kansas and Nebraska sparked more tensions related to whether to permit slavery there. To win Southern support for organizing Nebraska, Douglas added a provision declaring the Missouri Compromise to be invalid. The bill provided that the residents of the new territories could vote to determine whether they could allow slavery. Although Pierce's cabinet had made other proposals on this issue, Douglas and several southern Senators successfully persuaded Pierce to support Douglas' plan.

As the act was being debated, settlers on both sides of the slavery issue rushed into the state to be present for the voting. The passage of the Kansas–Nebraska Act resulted in so much violence between groups that the territory became known as Bleeding Kansas. Pro-slavery Border Ruffians, mostly from Missouri, illegally voted in the elections to set up the government, but Pierce recognized it anyway. When Free-Staters set up a shadow government, called the Topeka Constitution, Pierce termed their work an act of "rebellion". The president continued to recognize the pro-slavery legislature, which was dominated by Democrats, even after a Congressional investigative committee found its election to have been illegitimate. He dispatched federal troops to break up a meeting of the shadow government in Topeka.

The Kansas–Nebraska Act provoked outrage among northerners, who already viewed Pierce as kowtowing to slave-holding interests. This contributed to the Republican Party, as well as to critical assessments of Pierce as untrustworthy and easily manipulated. Having lost public confidence, Pierce was not nominated by his party for a second term. As a result of threats and the passions inspired by Kansas, Pierce hired a full-time bodyguard – the first president to do so.

Historians have ranked Pierce as among the least effective Presidents.[67] He was unable to steer a steady, prudent course that might have sustained a broad measure of support. Having publicly committed himself to an ill-considered position, he maintained it steadfastly, at a disastrous cost to his reputation.

Major legislation signed

- Signed Kansas–Nebraska Act

Cabinet

| The Pierce Cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | Franklin Pierce | 1853–1857 |

| Vice President | William R. King | 1853 |

| None | 1853–1857 | |

| Secretary of State | William L. Marcy | 1853–1857 |

| Secretary of Treasury | James Guthrie | 1853–1857 |

| Secretary of War | Jefferson Davis | 1853–1857 |

| Attorney General | Caleb Cushing | 1853–1857 |

| Postmaster General | James Campbell | 1853–1857 |

| Secretary of the Navy | James C. Dobbin | 1853–1857 |

| Secretary of the Interior | Robert McClelland | 1853–1857 |

Supreme Court appointments

Pierce appointed the following Justices to the Supreme Court of the United States:

States admitted to the Union

No states were admitted.

Later life

After losing the Democratic nomination for reelection in 1856, Pierce completed his term in 1857, and then traveled to Europe with his wife.[68] He returned to the U.S. in 1859 in time to comment on the growing sectional crisis between the South and the North, often criticizing Northern abolitionists for encouraging ugly feelings between the two sections.[69] In 1860, many Democrats viewed Pierce as a compromise choice for the presidential nomination as someone who could unite the Northern and Southern wings of the party, but Pierce declined to run.[70]

His wife, Jane Pierce died of tuberculosis in Andover, Massachusetts, on December 2, 1863. She was buried at Old North Cemetery in Concord, New Hampshire.[71][72]

During the Civil War, Pierce opposed President Abraham Lincoln's order suspending habeas corpus. Pierce argued that even in a time of war, the country should not abandon its protection of civil liberties.[73]

Pierce's stand won him admirers with the emerging Northern Peace Democrats, but enraged members of the Lincoln administration and supporters of the Union war effort. In 1862 Secretary of State William Seward sent Pierce a letter indicating that Pierce had been accused of being a member of the seditious Knights of the Golden Circle and asking Pierce whether it was true.[74] Outraged, Pierce denied the allegation and demanded that Seward put his response in the official files of the State Department. When that didn't happen, Pierce requested the assistance of a supporter in the Senate, Milton Latham of California, who requested copies of Seward–Pierce correspondence and read it into the Congressional Globe.[75][76]

In 1863 Pierce's reputation was greatly damaged in the North during the aftermath of Vicksburg. Union soldiers serving under General Hugh Ewing captured Confederate President Jefferson Davis' Fleetwood Plantation, and seized his personal correspondence, including letters to and from Pierce. Ewing turned over Davis' correspondence to William T. Sherman, Ewing's brother-in-law.[77] Ewing also sent copies of the letters to friends in Ohio. Those letters revealed Pierce's deep friendship with Davis and ambivalence about the goals of the war. As early as 1860, Pierce had written to Davis about "the madness of northern abolitionism". Another letter stated that he would "never justify, sustain, or in any way or to any extent uphold this cruel, heartless, aimless unnecessary war", and that "the true purpose of the war was to wipe out the states and destroy property".[77][78][79] Abolitionist author Harriet Beecher Stowe, who had long disliked Pierce, now referred to him as "the archtraitor," a sentiment that was widely shared.[77] Pierce's support for Union Army soldiers, including cash donations to assist the sick and wounded, did little to change the public's perception of Pierce as a Confederate sympathizer.[80]

In 1864, friends again put his name in play for the Democratic nomination, but he declined to run.[81]

On April 16, 1865, when news had spread of the assassination of President Lincoln, an angry mob of young teenagers gathered outside Pierce's home in Concord. Earlier that day a different mob had thrown black paint on the front porch of former President Millard Fillmore, upset that he had not hung black crepe to demonstrate that he mourned Lincoln's death. (Fillmore explained that he had been inside nursing his wife, who was ill, and the mob dispersed.)[82] The crowd in Concord wanted to know why Pierce's house was not dressed with black bunting and American flags as visual proof of his grief.[83] Pierce came outside to confront the crowd and said he, too, was saddened by Lincoln's passing. When a voice in the crowd yelled out, "Where is your flag?", Pierce became angry and recalled his family's long devotion to the country, including both his and his father's service in the military. He said he needed to display no flag to prove that he was a loyal American. The crowd soon quieted down and even cheered and applauded the former president as he went back into his home.[84]

Pierce had been a communicant of the Congregational church in Concord.[85] In 1865, on the second anniversary of his wife's death, Pierce was baptized into his wife's Episcopal faith at St. Paul's church in Concord.[86]

Death

Franklin Pierce died in Concord, New Hampshire, at 4:49 am on October 8, 1869, at 64 years old from cirrhosis of the liver.[87] President Ulysses S. Grant, who later defended Pierce's service in the Mexican War, declared a day of national mourning. Newspapers across the country carried lengthy front-page stories examining Pierce's colorful and controversial career. He was interred next to his wife and two of his sons, all of whom had predeceased him, in the Minot Enclosure in the Old North Cemetery of Concord.[88]

In his last will, which he signed January 22, 1868, he left an unusually large number of specific bequests to friends, family, and neighbors, including the children of Nathaniel Hawthorne. He left $1,000 in trust to the local library. The interest was used to purchase books. He left gifts of money, paintings, and other items to various people. The cane of General Lafayette was among the bequests. His nephew Frank Pierce received the residue.[89]

Legacy

Places named after President Pierce:

- Franklin Pierce University in Rindge, New Hampshire.

- Franklin Pierce School District, and namesake high school in Parkland, Washington

- Pierce Elementary School in Birmingham, Michigan.

- Pierce County in Washington, Nebraska, Georgia, and Wisconsin (but not the one in North Dakota, which was actually named after Gilbert Ashville Pierce)

- Pierce Street in Omaha, Nebraska

- Franklin Pierce Law Center in Concord, New Hampshire

- Mt. Pierce in the Presidential Range of the White Mountains, New Hampshire

- Franklin Pierce Lake (a reservoir in New Hampshire which covers the site of a log cabin which the Pierce family lived in and where Franklin may have been born)

- Pierceton, Indiana

Pierce was portrayed by Porter Hall in the 1944 film The Great Moment[90] and voiced by Sargent Shriver in the PBS documentary series The American President.[91]

Ancestors

| Ancestors of Franklin Pierce | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- ↑ The governor of New Hampshire was then elected annually; see also List of Governors of New Hampshire.

Citations

- ↑ Holt, Michael F.; Fitzgibbon Holt, Michael; Schlesinger, Jr., Arthur M; Wilentz, Sean (2010). Franklin Pierce Volume 14 of The American Presidents. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0805087192.

- ↑ Nathaniel Hawthorne (2010). "The Life of Franklin Pierce, 1852, Chapter 7". Retrieved October 3, 2010.

- ↑ Potter, David Morris; Fehrenbacher, Don Edward (1976). The Impending Crisis, 1848–1861. HarperCollins. p. 192. ISBN 978-0061319297.

- ↑ Robert Muccigrosso, ed., Research Guide to American Historical Biography (1988) 3:1237

- ↑ Philip B. Kunhardt, Peter W. Kunhardt The American President, 1999, page 57

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 1–8.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 10–15.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 16–19.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 28–32.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 28–33.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 33–43.

- ↑ John Farmer, G. Parker Lyon, editors, The New-Hampshire Annual Register, and United States Calendar, 1832, page 53

- ↑ Brian Matthew Jordan, Triumphant Mourner: The Tragic Dimension of Franklin Pierce, 2003, page 31

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 44–47.

- ↑ Jean H. Baker, "Franklin Pierce: Life Before the Presidency", American President: An Online Reference Resource (University of Virginia), retrieved December 10, 2010, "In 1834, the congressman married Jane Means Appleton, the daughter of Jesse Appleton, who had been President of Bowdoin College, Pierce's alma mater. Franklin and Jane Pierce seemingly had little in common, and the marriage would sometimes be a troubled one. The bride's family were staunch Whigs, a party largely formed to oppose Andrew Jackson, who Pierce revered. Socially, Jane Pierce was reserved and shy, the polar opposite of her new husband."

- ↑ "Franklin Pierce", Internet Public Library

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 47–57.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Wallner (2004), pp. 57–59.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 71–72.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), p. 67.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), p. 92.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 59–61.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 64–69.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 68, 91–92.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 69–72.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), p. 80.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 78–84.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 84–90.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 91–92.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), p. 79.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), p. 86.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 98–101.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 93–95.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 103–110.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 131–132.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 111–122.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 131–135.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 135–144.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 144–147.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 147–154.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 154–157.

- ↑ Ulysses S. Grant, Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant, Volume 1, 1892, pages 146-147

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 157–161.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 161–171.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 171–172.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 173–180.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 181–184; Gara (1991), pp, 23–29.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 184–197; Gara (1991), pp. 32–33.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 197–202; Gara (1991), pp. 33–34.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 210–213; Gara (1991), pp. 36–38. Quote from Gara, 38.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), p. 231; Gara (1991), p. 38.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), p. 206; Gara (1991), p. 38.

- ↑ Gara (1991), p. 38.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), p. 203.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 229–230; Gara (1991), p. 39.

- ↑ Wallner (2004), pp. 241–245; Gara (1991), p 43–44.

- ↑ "Franklin Pierce: Defining Democracy in America". New Hampshire Historical Society. 2010. Retrieved October 3, 2010.

- ↑ Sandra L. Quinn-Musgrove, Sandra L. Quinn-Musgrove Sanford Kanter, America's Royalty: All the Presidents' Children, 1995, pages 86 to 87

- ↑ Edward T. James, Janet Wilson James, Paul S. Boyer, Radcliffe College, Notable American Women: 1607–1950 Volume 2 (P–Z), 1971, page 67

- ↑ "Franklin Pierce: Inaugural Address. U.S. Inaugural Addresses. 1989". Bartleby.com. Retrieved February 14, 2010.

- ↑ http://www.franklinpierce.org/

- ↑ Tribble, Mimi (2004). The American Presidents. New York, New York: Sterling Publishing Co. p. 19. ISBN 1-4027-1794-6.

- ↑ Brinkley, A. and Dyer, D. The American Presidency, 2004. Houghton Mifflin Company.

- ↑ Franklin Pierce | The White House. Whitehouse.gov (2013-07-26). Retrieved on 2013-08-02.

- ↑ Franklin Pierce. Americanhistory.si.edu (2012-03-14). Retrieved on 2013-08-02.

- ↑ James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (New York: Ballantine Books, 1989, pp. 119–20.

- ↑ William C. Spragens, Popular Images of American Presidents, 1988, page 297

- ↑ Oxford University Press, American National Biography, Park-Pushmataha, 1999, page 497

- ↑ Robert V. Remini, Terry Golway, Fellow Citizens: The Penguin Book of U.S. Presidential Inaugural Addresses, 2008

- ↑ Bob Navarro, The Era of Change: Executives and Events in a Period of Rapid Expansion, 2006, page 321

- ↑ Mathew Manweller, Chronology of the U.S. Presidency, 2012, page 429

- ↑ Michael F. Holt, Franklin Pierce: The American Presidents Series: The 14th President, 1853-1857, 2010, page 125

- ↑ Garry Boulard, The Expatriation of Franklin Pierce, 2006, page 78

- ↑ Max J. Skidmore, After the White House: Former Presidents as Private Citizens, 2004, page 69

- ↑ United States War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series II, Volume II, 1897, page 1266

- ↑ Colonial Society of Massachusetts, The New England Quarterly, Volume 34, 1961, page 385

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 77.2 Allen, Felicity (1999). Jefferson Davis, Unconquerable Heart. University of Missouri Press. pp. 359–360. ISBN 0-8262-1219-0. Retrieved November 23, 2007.

- ↑ Robert Melvin to Jefferson Davis, July 22, 1863, in Mississippi in the Confederacy: As They Saw it, ed. John K. Bettersworth, pp. 210–12

- ↑ Crist, Lynda Lasswel. A Bibliographical Note: Jefferson Davis's Personal Library: All Lost, Some Found. Journal of Mississippi History 45 (1983): 191–93

- ↑ Skidmore, After the White House

- ↑ Herman Hattaway, Ethan Sepp Rafuse, The Ongoing Civil War: New Versions of Old Stories, 2004, page 71

- ↑ John E. Crawford, Millard Fillmore: A Bibliography, 2002, page 257

- ↑ Brian Matthew Jordan, Triumphant Mourner: The Tragic Dimension of Franklin Pierce, 2003, pages 105-106

- ↑ Holt, Franklin Pierce: The American Presidents Series, page 127

- ↑ Henry Woldmar Ruoff, The Century Book of Facts, 1906, page 350

- ↑ Brian Matthew Jordan, Triumphant Mourner, page 106

- ↑ Strange Facts About Presidents of the United States | strange true facts|strange weird stuff|weird diseases. Nerdygaga.com. Retrieved on 2013-08-02.

- ↑ Franklin Pierce page, Find A Grave

- ↑ Wills of the U.S. Presidents, ed. by Herbert R. Collins and David B. Weaver, New York: Communications Channels, Inc, 1976, pp. 108–113. ISBN 0-916164-01-2

- ↑ Monush, Barry. Encyclopedia of Hollywood Film Actors: From the silent era to 1965, Hal Leonard Corporation, 2003 ISBN 1-55783-551-9

- ↑ http://www.imdb.com/character/ch0029450/

Bibliography

- Allen, Felicity. Jefferson Davis, Unconquerable Heart. St. Louis, Missouri: University of Missouri Press. 1999. ISBN 0-8262-1219-0.

- Bergen, Anthony. (2010) "Pierce and the Consequences of Ambition"

- Boulard, Garry, "The Expatriation of Franklin Pierce—The Story of a President and the Civil War". (iUniverse, 2006)

- Brinkley, A. and Dyer, D. The American Presidency. 2004. Houghton Mifflin Company.

- DiConsiglio, John. Franklin Pierce. Vol. 14. New York: Children's Press-Scholastic, 2004. ISBN 0-516-24235-0

- Gara, Larry, The Presidency of Franklin Pierce (1991), standard history of his administration

- Nichols; Roy Franklin. Franklin Pierce, Young Hickory of the Granite Hills (1931), standard biography

- Nichols; Roy Franklin.The Democratic Machine, 1850–1854. Columbia University Press, 1923. online version

- Potter, David M, The Impending Crisis, 1848–1861. New York, New York: Harper & Row, 1976. ISBN 0-06-013403-8.

- Taylor; Michael J.C. "Governing the Devil in Hell: 'Bleeding Kansas' and the Destruction of the Franklin Pierce Presidency (1854–1856)" White House Studies, Vol. 1, 2001, pp 185–205

- Wallner, Peter A. (2004). Franklin Pierce: New Hampshire's Favorite Son. Concord, New Hampshire: Plaidswede. ISBN 0-9755216-1-6.

- Wallner, Peter A. (2007). Franklin Pierce: Martyr for the Union. Concord, New Hampshire: Plaidswede. ISBN 978-0-9790784-2-2.

External links

|

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: |

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Franklin Pierce |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Franklin Pierce. |

- Works by Franklin Pierce at Project Gutenberg

- Franklin Pierce: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- White House biography

- Pierce 200 site

- Inaugural Address

- The Life of Franklin Pierce By Nathaniel Hawthorne

- Pierce Manse

- State of the Union: 1853, 1854, 1855, 1856

- Franklin Pierce and His Services in the Valley of Mexico

- The Health and Medical History of President: Franklin Pierce

- Essays on Pierce and each member of his cabinet and First Lady

- Franklin Pierce at the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

- The life of Gen. Frank. Pierce, of New Hampshire, the Democratic candidate for president of the United States by D.W. Barlett

- Franklin Pierce at C-SPAN's American Presidents: Life Portraits

- Booknotes interview with Peter Wallner on Franklin Pierce: New Hampshire's Favorite Son, November 28, 2004.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|