Frank–Wolfe algorithm

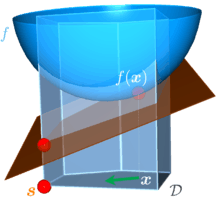

The Frank–Wolfe algorithm is a simple iterative first-order optimization algorithm for constrained convex optimization. Also known as the conditional gradient method,[1] reduced gradient algorithm and the convex combination algorithm, the method was originally proposed by Marguerite Frank and Philip Wolfe in 1956.[2] In each iteration, the Frank–Wolfe algorithm considers a linear approximation of the objective function, and moves slightly towards a minimizer of this linear function (taken over the same domain).

Problem statement

- Minimize

- subject to

.

.

Where the function  is convex and differentiable, and the domain / feasible set

is convex and differentiable, and the domain / feasible set  is a convex and bounded set in some vector space.

is a convex and bounded set in some vector space.

Algorithm

- Initialization: Let

, and let

, and let  be any point in

be any point in  .

.

- Step 1. Direction-finding subproblem: Find

solving

solving

- Minimize

- Subject to

- Minimize

- (Interpretation: Minimize the linear approximation of the problem given by the first-order Taylor approximation of

around

around  .)

.)

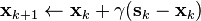

- Step 2. Step size determination: Set

, or alternatively find

, or alternatively find  that minimizes

that minimizes  subject to

subject to  .

.

- Step 3. Update: Let

, let

, let  and go to Step 1.

and go to Step 1.

Properties

While competing methods such as gradient descent for constrained optimization require a projection step back to the feasible set in each iteration, the Frank–Wolfe algorithm only needs the solution of a linear problem over the same set in each iteration, and automatically stays in the feasible set.

The convergence of the Frank–Wolfe algorithm is sublinear in general: the error to the optimum is  after k iterations. The same convergence rate can also be shown if the sub-problems are only solved approximately.[3]

after k iterations. The same convergence rate can also be shown if the sub-problems are only solved approximately.[3]

The iterates of the algorithm can always be represented as a sparse convex combination of the extreme points of the feasible set, which has helped to the popularity of the algorithm for sparse greedy optimization in machine learning and signal processing problems,[4] as well as for example the optimization of minimum–cost flows in transportation networks.[5]

If the feasible set is given by a set of linear constraints, then the subproblem to be solved in each iteration becomes a linear program.

While the worst-case convergence rate with  can not be improved in general, faster convergence can be obtained for special problem classes, such as some strongly convex problems.[6]

can not be improved in general, faster convergence can be obtained for special problem classes, such as some strongly convex problems.[6]

Lower bounds on the solution value, and primal-dual analysis

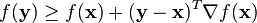

Since  is convex,

is convex,  is always above the tangent plane of

is always above the tangent plane of  at any point

at any point  :

:

This holds in particular for the (unknown) optimal solution  . The best lower bound with respect to a given point

. The best lower bound with respect to a given point  is given by

is given by

The latter optimization problem is solved in every iteration of the Frank-Wolfe algorithm, therefore the solution  of the direction-finding subproblem of the

of the direction-finding subproblem of the  -th iteration can be used to determine increasing lower bounds

-th iteration can be used to determine increasing lower bounds  during each iteration by setting

during each iteration by setting  and

and

Such lower bounds on the unknown optimal value are important in practice because they can be used as a stopping criterion, and give an efficient certificate of the approximation quality in every iteration, since always  .

.

It has been shown that this corresponding duality gap, that is the difference between  and the lower bound

and the lower bound  , decreases with the same convergence rate, i.e.

, decreases with the same convergence rate, i.e.

Notes

- ↑ Levitin, E. S.; Polyak, B. T. (1966). "Constrained minimization methods". USSR Computational Mathematics and Mathematical Physics 6 (5): 1. doi:10.1016/0041-5553(66)90114-5.

- ↑ Frank, M.; Wolfe, P. (1956). "An algorithm for quadratic programming". Naval Research Logistics Quarterly 3: 95. doi:10.1002/nav.3800030109.

- ↑ Dunn, J. C.; Harshbarger, S. (1978). "Conditional gradient algorithms with open loop step size rules". Journal of Mathematical Analysis and Applications 62 (2): 432. doi:10.1016/0022-247X(78)90137-3.

- ↑ Clarkson, K. L. (2010). "Coresets, sparse greedy approximation, and the Frank-Wolfe algorithm". ACM Transactions on Algorithms 6 (4): 1. doi:10.1145/1824777.1824783.

- ↑ Fukushima, M. (1984). "A modified Frank-Wolfe algorithm for solving the traffic assignment problem". Transportation Research Part B: Methodological 18 (2): 169–153. doi:10.1016/0191-2615(84)90029-8.

- ↑ Bertsekas, Dimitri (2003). Nonlinear Programming. Athena Scientific. p. 222. ISBN 1-886529-00-0.

Bibliography

- Jaggi, Martin (2013). "Revisiting Frank-Wolfe: Projection-Free Sparse Convex Optimization". Journal of Machine Learning Research: Workshop and Conference Proceedings 28 (1): 427–435. (Overview paper)

- The Frank-Wolfe algorithm description

See also

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||