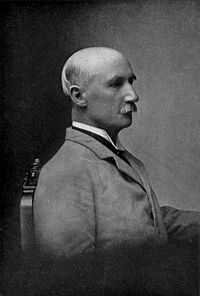

Francis Brinkley

| Francis Brinkley | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

30 December 1841 Leinster, Ireland |

| Died |

12 October 1912 (aged 70) Tokyo, Japan |

| Nationality | Irish |

| Occupation | military advisor, journalist |

Francis Brinkley (30 December 1841 – 12 October 1912[1]) was an Irish newspaper owner, editor and scholar who resided in Meiji period Japan for over 40 years, where he was the author of numerous books on Japanese culture, art and architecture, and an English-Japanese Dictionary. He was also known as Frank Brinkley or as Captain Francis Brinkley, and was the great uncle of Cyril Connolly.

Early life

In 1841, Frank Brinkley was born at Parsonstown House, Co. Meath, the thirteenth and youngest child of Matthew Brinkley (1797–1855) J.P., of Parsonstown, and his wife Harriet Graves (1800–1855).[2] His paternal grandfather, John Brinkley, was the last Bishop of Cloyne and the first Royal Astronomer of Ireland, while his maternal grandfather, Richard Graves, was also a Senior Fellow of Trinity College and the Dean of Ardagh. One of Brinkley's sisters, Jane (Brinkley) Vernon of Clontarf Castle, was the grandmother of Cyril Connolly. Another sister, Anna, became the Dowager Countess of Kingston after the death of her first husband, James King, 5th Earl of Kingston, and was the last person to live at Mitchelstown Castle. Through his mother's family Brinkley was related to Richard Francis Burton, a distinguished linguist who shared Brinkley's passion for foreign culture.

Brinkley went to Royal School Dungannon before entering Trinity College, where he received the highest records in mathematics and classics. After graduating he chose upon a military career and was subsequently accepted at the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich, becoming an artillery officer. In this capacity his cousin, Sir Richard Graves MacDonnell the 6th Governor of Hong Kong (1866–1872), invited him out to the east to serve as his Aide-de-camp and Adjutant.

In 1866, on his way to Hong Kong, Brinkley visited Nagasaki and witnessed a duel between two samurai warriors. Once the victor had slain his opponent he immediately covered him in his haori, and "knelt down with hands clasped in prayer". It is said that Brinkley was so impressed by the conduct of the Japanese warrior that this enticed him to live in Japan permanently.

Life in Japan

In 1867 Captain Brinkley returned to Japan, never again to return home. Attached to the British-Japanese Legation, and still an officer in the Royal Artillery, he was assistant military attache to the Japanese Embassy. He resigned his commission in 1871 to take up the post of foreign advisor to the new Meiji government, and taught artillery techniques to the new Imperial Japanese Navy at the Naval Gunnery School. He mastered the Japanese language soon after his arrival, and both spoke and wrote it well.

In 1878 he was invited to teach mathematics at the Imperial College of Engineering, which later became part of Tokyo Imperial University, remaining in this post for two and a half years.

In the same year he married Yasuko Tanaka, a daughter of a former samurai from the Mito clan. Interracial marriages could be registered under Japanese law from 1873. Brinkley sought but was refused permission by the British Legation to register his marriage in order that his wife would have undisputed claim to British nationality (she forfeited her Japanese nationality by marrying him). He fought this refusal and eventually succeeded by appealing to the British judiciary, with the help of some influential friends. They were the parents of two daughters and a son named Jack Ronald Brinkley (1887–1964).

In 1881 until his death he owned and edited the Japan Mail newspaper (later merged with the Japan Times), receiving financial support from the Japanese government and consequently maintaining a pro-Japanese stance. The newspaper was perhaps the most influential and widely read English language newspaper in the far East.[citation needed]

After the First Sino-Japanese War Brinkley became the Tokyo-based correspondent for The Times of London, and gained fame for his dispatches during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905. He was awarded the Order of the Sacred Treasure by Emperor Meiji for his contributions to better Anglo-Japanese relations. He was also an adviser to the Nippon Yusen Kaisha, Japan's largest shipping line. F.A. MacKenzie, a prominent English journalist, wrote:

Captain Brinkley's great knowledge of Japanese life and language is admitted and admired by all. His independence of judgment is, however, weakened by his close official connection with the Japanese Government and by his personal interest in Japanese industry. His journal is regarded generally as a government mouth-piece, and he has succeeded in making himself a more vigorous advocate of the Japanese claims than even the Japanese themselves. It can safely be forecasted that whenever a dispute arises between Japanese and British interests, Captain Brinkley and his journal will play the part, through thick and thin, of defenders of the Japanese.

Brinkley's last dispatch to The Times was written from his deathbed in 1912, reporting on a seppuku: Emperor Meiji had recently died and to show fealty to the deceased emperor, General Nogi Maresuke together with his wife committed hara-kiri.

Private life

Frank Brinkley had many hobbies which included gardening, collecting Japanese art and pottery, cricket, tennis, horse riding and hunting. Part of his significant collection of art and pottery was donated to various museums around the world, but the most part was reduced to rubble and ash after the Great Tokyo earthquake and World War II.

He wrote books for English beginners interested in the Japanese language, and his grammar books and English-Japanese Dictionary (compiled with Fumio Nanjo and Yukichika Iwasaki) were regarded as the definitive books on the subject for those studying English in the latter half of the Meiji period.

He wrote much on Japanese history and Japanese art. His book A History of the Japanese People, which was published after his death by The Times in 1915, covered Japanese history, fine arts and literature from the origins of the Japanese race up until the latter half of the Meiji period.

Death

In 1912, at the age of 71 and one month after General Nogi's death, Francis Brinkley died. At his funeral, the mourners included the Speaker of the House of Peers, Iesato Tokugawa, the Minister of the Navy Saitō Makoto, and the Foreign Minister Kosai Uchida. He is buried in the foreign section of the Aoyama Reien cemetery in central Tokyo.[3]

After his death Ernest Satow wrote of Brinkley to Frederick Victor Dickins on 21 November 1912: "I have not seen any fuller memoir of Brinkley than what appeared in "The Times". As you perhaps know I did not trust him. Who wrote "The Times" notice I cannot imagine. As you say, it was the work of an ignorant person."[4]

On his death bed Frank Brinkley had told his son, Jack, of an episode that occurred during the Russo-Japanese War. After the Japanese had defeated the Russians at the Battle of Mukden, the Chief of the General Staff, Gentarō Kodama, rushed home in secret to urge the Japanese Government to conclude a treaty with Russia. At the time it was a hugely consequential secret and yet he confided this national secret to Brinkley, the foreign correspondent of The Times, demonstrating the utmost confidence in which the Chief of the General Staff held Brinkley.

Publications

Brinkley's published works include:

- Japan (1901)

- Japan and China (1903)

- A History of the Japanese people(1915)

- Unabridged Japanese-English Dictionary'

- various articles on Japan in encyclopaedias.

See also

Notes

References

- Hoare, James E. (1999). "Captain Francis Brinkley (1841–1912): Yatoi, Scholar and Apologist" in Britain & Japan: Biographical Portraits, Vol. III (edited by James E. Hoare). London, Japan Library, 1999. ISBN 1-873410-89-1

External links

Works written by or about Frank Brinkley at Wikisource

Works written by or about Frank Brinkley at Wikisource- Francis Brinkley

|