Fractional reserve banking

Banking A series on financial services |

|---|

|

|

Types of banks Central bank Advising bank · Commercial bank Community development bank Cooperative bank · Credit union Custodian bank · Depository bank Export credit agency Investment bank · Industrial bank Merchant bank · Mutual savings bank National bank · Offshore bank Postal savings system Private bank · Public bank · Retail Bank Savings and loan association Savings bank · Universal bank more... |

|

Bank cards |

|

Funds transfer Electronic funds transfer Wire transfer · Cheque · SWIFT Automated Clearing House Electronic bill payment · Giro |

|

Banking terms Loan · Money creation Fractional reserve banking Automatic teller machine Bank regulation · Anonymous banking Islamic banking · Private banking Ethical banking |

| Finance |

|---|

|

|

Fractional-reserve banking is the practice whereby a bank retains reserves in an amount equal to only a portion of the amount of its customers' deposits to satisfy potential demands for withdrawals. Reserves are held at the bank as currency, or as deposits reflected in the bank's accounts at the central bank. The remainder of customer-deposited funds is used to fund investments or loans that the bank makes to other customers. [citation needed] Most of these loaned funds are later redeposited into other banks, allowing further lending. Because bank deposits are usually considered money in their own right, fractional-reserve banking permits the money supply to grow to a multiple (called the money multiplier) of the underlying reserves of base money originally created by the central bank.[1][2]

To mitigate the risks of bank runs (when a large proportion of depositors seek withdrawal of their demand deposits at the same time) or, when problems are extreme and widespread, systemic crises, the governments of most countries regulate and oversee commercial banks, provide deposit insurance and act as lender of last resort to commercial banks.[1][2] In most countries, the central bank (or other monetary authority) regulates bank credit creation, imposing reserve requirements and other capital adequacy ratios. This limits the amount of money creation that occurs in the commercial banking system, and helps ensure that banks have enough funds to meet the demand for withdrawals.[2]

Fractional-reserve banking is the current form of banking in all countries worldwide.[3]

History

Fractional-reserve banking predates the existence of governmental monetary authorities and originated many centuries ago in bankers' realization that generally not all depositors demand payment at the same time.[4]

Savers looking to keep their valuables in safekeeping depositories deposited gold and silver at goldsmiths, receiving in exchange a note for their deposit (see Bank of Amsterdam). These notes gained acceptance as a medium of exchange for commercial transactions and thus became as an early form of circulating paper money.[5]

As the notes were used directly in trade, the goldsmiths observed that people would not usually redeem all their notes at the same time, and they saw the opportunity to invest their coin reserves in interest-bearing loans and bills. This generated income for the goldsmiths but left them with more notes on issue than reserves with which to pay them. A process was started that altered the role of the goldsmiths from passive guardians of bullion, charging fees for safe storage, to interest-paying and interest-earning banks. Thus fractional-reserve banking was born.

However, if creditors (note holders of gold originally deposited) lost faith in the ability of a bank to pay their notes, many would try to redeem their notes at the same time. If in response a bank could not raise enough funds by calling in loans or selling bills, it either went into insolvency or defaulted on its notes. Such a situation is called a bank run and caused the demise of many early banks.[5]

Starting in the late 1600s nations began to establish central banks which were given the legal power to set reserve requirements and to issue the reserve assets, or monetary base, in which form such reserves are required to be held.[6] The reciprocal of the reserve requirement, called the money multiplier, limits the size to which the transactions in money supply may grow for a given level of reserves in the banking system. In order to mitigate the impact of bank failures and financial crises, governments created central banks – public (or semi-public) institutions that have the authority to centralize the storage of precious metal bullion amongst private banks to allow transfer of gold in case of bank runs, regulate commercial banks, impose reserve requirements, and act as lender-of-last-resort if any bank faced a bank run. The emergence of central banks reduced the risk of bank runs inherent in fractional-reserve banking and allowed the practice to continue as it does today.[2][7]

Over time, economists, central banks, and governments have changed their views as to the policy variables which should be targeted by monetary authorities. These have included interest rates, reserve requirements, and various measures of the money supply and monetary base.

How it works

In most legal systems, a bank deposit is not a bailment. In other words, the funds deposited are no longer the property of the customer. The funds become the property of the bank, and the customer in turn receives an asset called a deposit account (a checking or savings account). That deposit account is a liability of the bank on the bank's books and on its balance sheet. Because the bank is authorized by law to create credit up to an amount equal to a multiple of the amount of its reserves, the bank's reserves on hand to satisfy payment of deposit liabilities amount to only a fraction of the total amount which the bank is obligated to pay in satisfaction of its demand deposits.

Fractional-reserve banking ordinarily functions smoothly. Relatively few depositors demand payment at any given time, and banks maintain a buffer of reserves to cover depositors' cash withdrawals and other demands for funds. However, during a bank run or a generalized financial crisis, demands for withdrawal can exceed the bank's funding buffer, and the bank will be forced to raise additional reserves to avoid defaulting on its obligations. A bank can raise funds from additional borrowings (e.g., by borrowing in the interbank lending market or from the central bank), by selling assets, or by calling in short-term loans. If creditors are afraid that the bank is running out of reserves or is insolvent, they have an incentive to redeem their deposits as soon as possible before other depositors access the remaining reserves. Thus the fear of a bank run can actually precipitate the crisis.

Many of the practices of contemporary bank regulation and central banking, including centralized clearing of payments, central bank lending to member banks, regulatory auditing, and government-administered deposit insurance, are designed to prevent the occurrence of such bank runs.

Economic function

Fractional-reserve banking allows banks to create credit in the form of bank deposits, which represent immediate liquidity to depositors. The banks also provide longer-term loans to borrowers, and act as financial intermediaries for those funds.[2][8] Less liquid forms of deposit (such as time deposits) or riskier classes of financial assets (such as equities or long-term bonds) may lock up a depositor's wealth for a period of time, making it unavailable for use on demand. This "borrowing short, lending long," or maturity transformation function of fractional-reserve banking is a role that many economists consider to be an important function of the commercial banking system.[9]

Additionally, according to macroeconomic theory, a well-regulated fractional-reserve bank system also benefits the economy by providing regulators with powerful tools for influencing the money supply and interest rates. Many economists believe that these should be adjusted by the government to promote macroeconomic stability.[10]

Modern central banking allows banks to practice fractional-reserve banking with inter-bank business transactions with a reduced risk of bankruptcy. The process of fractional-reserve banking expands the money supply of the economy but also increases the risk that a bank cannot meet its depositor withdrawals.[11][12]

Money creation process

There are two types of money in a fractional-reserve banking system operating with a central bank:[13][14][15]

- Central bank money: money created or adopted by the central bank regardless of its form – precious metals, commodity certificates, banknotes, coins, electronic money loaned to commercial banks, or anything else the central bank chooses as its form of money

- Commercial bank money: demand deposits in the commercial banking system; sometimes referred to as "chequebook money"

When a deposit of central bank money is made at a commercial bank, the central bank money is removed from circulation and added to the commercial banks' reserves (it is no longer counted as part of M1 money supply). Simultaneously, an equal amount of new commercial bank money is created in the form of bank deposits. When a loan is made by the commercial bank (which keeps only a fraction of the central bank money as reserves), using the central bank money from the commercial bank's reserves, the m1 money supply expands by the size of the loan.[2] This process is called "deposit multiplication".

Example of deposit multiplication

The table below displays the relending model of how loans are funded and how the money supply is affected. It also shows how central bank money is used to create commercial bank money from an initial deposit of $100 of central bank money. In the example, the initial deposit is lent out 10 times with a fractional-reserve rate of 20% to ultimately create $500 of commercial bank money (it is important to note that the 20% reserve rate used here is for ease of illustration, actual reserve requirements are usually a lot lower, for example around 3% in the USA and UK). Each successive bank involved in this process creates new commercial bank money on a diminishing portion of the original deposit of central bank money. This is because banks only lend out a portion of the central bank money deposited, in order to fulfill reserve requirements and to ensure that they always have enough reserves on hand to meet normal transaction demands.

The relending model begins when an initial $100 deposit of central bank money is made into Bank A. Bank A takes 20 percent of it, or $20, and sets it aside as reserves, and then loans out the remaining 80 percent, or $80. At this point, the money supply actually totals $180, not $100, because the bank has loaned out $80 of the central bank money, kept $20 of central bank money in reserve (not part of the money supply), and substituted a newly created $100 IOU claim for the depositor that acts equivalently to and can be implicitly redeemed for central bank money (the depositor can transfer it to another account, write a check on it, demand his cash back, etc.). These claims by depositors on banks are termed demand deposits or commercial bank money and are simply recorded in a bank's accounts as a liability (specifically, an IOU to the depositor). From a depositor's perspective, commercial bank money is equivalent to central bank money – it is impossible to tell the two forms of money apart unless a bank run occurs.[2]

At this point in the relending model, Bank A now only has $20 of central bank money on its books. The loan recipient is holding $80 in central bank money, but he soon spends the $80. The receiver of that $80 then deposits it into Bank B. Bank B is now in the same situation as Bank A started with, except it has a deposit of $80 of central bank money instead of $100. Similar to Bank A, Bank B sets aside 20 percent of that $80, or $16, as reserves and lends out the remaining $64, increasing money supply by $64. As the process continues, more commercial bank money is created. To simplify the table, a different bank is used for each deposit. In the real world, the money a bank lends may end up in the same bank so that it then has more money to lend out.

| Individual Bank | Amount Deposited | Lent Out | Reserves |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 100 | 80 | 20 |

| B | 80 | 64 | 16 |

| C | 64 | 51.20 | 12.80 |

| D | 51.20 | 40.96 | 10.24 |

| E | 40.96 | 32.77 | 8.19 |

| F | 32.77 | 26.21 | 6.55 |

| G | 26.21 | 20.97 | 5.24 |

| H | 20.97 | 16.78 | 4.19 |

| I | 16.78 | 13.42 | 3.36 |

| J | 13.42 | 10.74 | 2.68 |

| K | 10.74 | 0.0 | 10.74 |

| Total Amount of Deposits: | Total Amount Lent Out: | Total Reserves: | |

| 457.05 | 357.05 | 100 | |

Although no new money was physically created in addition to the initial $100 deposit, new commercial bank money is created through loans. The boxes marked in red show the location of the original $100 deposit throughout the entire process. The total reserves will always equal the original amount, which in this case is $100. As this process continues, more commercial bank money is created. The amounts in each step decrease towards a limit. If a graph is made showing the accumulation of deposits, one can see that the graph is curved and approaches a limit. This limit is the maximum amount of money that can be created with a given reserve rate. When the reserve rate is 20%, as in the example above, the maximum amount of total deposits that can be created is $500 and the maximum increase in the money supply is $400.

For an individual bank, the deposit is considered a liability whereas the loan it gives out and the reserves are considered assets. Deposits will always be equal to loans plus a bank's reserves, since loans and reserves are created from deposits. This is the basis for a bank's balance sheet. Fractional-reserve banking allows the money supply to expand or contract. Generally the expansion or contraction of the money supply is dictated by the balance between the rate of new loans being created and the rate of existing loans being repaid or defaulted on. The balance between these two rates can be influenced to some degree by actions of the central bank. However, the central bank has no direct control over the amount of money created by commercial (or high street) banks.

Money multiplier

The most common mechanism used to measure this increase in the money supply is typically called the "money multiplier". It calculates the maximum amount of money that an initial deposit can be expanded to with a given reserve ratio.

Formula

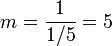

The money multiplier, m, is the inverse of the reserve requirement, R:[16]

- Example

For example, with the reserve ratio of 20 percent, this reserve ratio, R, can also be expressed as a fraction:

So then the money multiplier, m, will be calculated as:

This number is multiplied by the initial deposit to show the maximum amount of money it can be expanded to.

The money creation process is also affected by the currency drain ratio (the propensity of the public to hold banknotes rather than deposit them with a commercial bank), and the safety reserve ratio (excess reserves beyond the legal requirement that commercial banks voluntarily hold – usually a small amount). Data for "excess" reserves and vault cash are published regularly by the Federal Reserve in the United States.[17] In practice, the actual money multiplier varies over time, and may be substantially lower than the theoretical maximum.[18]

Money supplies around the world

Fractional-reserve banking determines the relationship between the amount of "central bank money" in the official money supply statistics and the total money supply. Most of the money in these systems is "commercial bank money". Fractional-reserve banking allows the creation of commercial bank money, which increases the money supply through the deposit creation multiplier. The issue of money through the banking system is a mechanism of monetary transmission, which a central bank can influence only indirectly by raising or lowering interest rates (although banking regulations may also be adjusted to influence the money supply, depending on the circumstances).

This table gives an outline of the makeup of money supplies worldwide. Most of the money in any given money supply consists of commercial bank money.[13] The value of commercial bank money is based on the fact that it can be exchanged freely at a bank for central bank money.[13][14]

The actual increase in the money supply through this process may be lower, as (at each step) banks may choose to hold reserves in excess of the statutory minimum, borrowers may let some funds sit idle, and some members of the public may choose to hold cash, and there also may be delays or frictions in the lending process.[19] Government regulations may also be used to limit the money creation process by preventing banks from giving out loans even though the reserve requirements have been fulfilled.[20]

Regulation

Because the nature of fractional-reserve banking involves the possibility of bank runs, central banks have been created throughout the world to address these problems.[7][21]

Central banks

Government controls and bank regulations related to fractional-reserve banking have generally been used to impose restrictive requirements on note issue and deposit taking on the one hand, and to provide relief from bankruptcy and creditor claims, and/or protect creditors with government funds, when banks defaulted on the other hand. Such measures have included:

- Minimum required reserve ratios (RRRs)

- Minimum capital ratios

- Government bond deposit requirements for note issue

- 100% Marginal Reserve requirements for note issue, such as the Bank Charter Act 1844 (UK)

- Sanction on bank defaults and protection from creditors for many months or even years, and

- Central bank support for distressed banks, and government guarantee funds for notes and deposits, both to counteract bank runs and to protect bank creditors.

Reserve requirements

The currently prevailing view of reserve requirements is that they are intended to prevent banks from:

- generating too much money by making too many loans against the narrow money deposit base;

- having a shortage of cash when large deposits are withdrawn (although the reserve is thought to be a legal minimum, it is understood that in a crisis or bank run, reserves may be made available on a temporary basis).

In practice, some central banks do not require reserves to be held, and in some countries that do, such as the USA and the EU they are not required to be held during the day when the banks are lending, and banks can borrow from other banks at near the central bank policy rate to ensure they have the necessary amount of required reserves by the close of business. Required reserves are therefore considered by some central bankers, monetary economists and textbooks to only play a very small role in limiting money creation in these countries. Most commentators agree however, that they help the banks have sufficient supplies of highly liquid assets, so that the system operates in an orderly fashion and maintains public confidence. The UK for example, which does not have required reserves, does have requirements that the banks keep a certain amount of cash, and in Australia while there are no reserve requirements, there are a variety of requirements to ensure the banks have a stabilising ratio of liquid assets, such as deposits held with local banks. Individual countries adhere to varying required reserve ratios which have changed over time.

In addition to reserve requirements, there are other required financial ratios that affect the amount of loans that a bank can fund. The capital requirement ratio is perhaps the most important of these other required ratios. When there are no mandatory reserve requirements, which are considered by some economists to restrict lending, the capital requirement ratio acts to prevent an infinite amount of bank lending.

Liquidity and capital management for a bank

To avoid defaulting on its obligations, the bank must maintain a minimal reserve ratio that it fixes in accordance with, notably, regulations and its liabilities. In practice this means that the bank sets a reserve ratio target and responds when the actual ratio falls below the target. Such response can be, for instance:

- Selling or redeeming other assets, or securitization of illiquid assets,

- Restricting investment in new loans,

- Borrowing funds (whether repayable on demand or at a fixed maturity),

- Issuing additional capital instruments, or

- Reducing dividends.[citation needed]

Because different funding options have different costs, and differ in reliability, banks maintain a stock of low cost and reliable sources of liquidity such as:

- Demand deposits with other banks

- High quality marketable debt securities

- Committed lines of credit with other banks[citation needed]

As with reserves, other sources of liquidity are managed with targets.

The ability of the bank to borrow money reliably and economically is crucial, which is why confidence in the bank's creditworthiness is important to its liquidity. This means that the bank needs to maintain adequate capitalisation and to effectively control its exposures to risk in order to continue its operations. If creditors doubt the bank's assets are worth more than its liabilities, all demand creditors have an incentive to demand payment immediately, causing a bank run to occur.[citation needed]

Contemporary bank management methods for liquidity are based on maturity analysis of all the bank's assets and liabilities (off balance sheet exposures may also be included). Assets and liabilities are put into residual contractual maturity buckets such as 'on demand', 'less than 1 month', '2–3 months' etc. These residual contractual maturities may be adjusted to account for expected counter party behaviour such as early loan repayments due to borrowers refinancing and expected renewals of term deposits to give forecast cash flows. This analysis highlights any large future net outflows of cash and enables the bank to respond before they occur. Scenario analysis may also be conducted, depicting scenarios including stress scenarios such as a bank-specific crisis.[citation needed]

Hypothetical example of a bank balance sheet and financial ratios

An example of fractional-reserve banking, and the calculation of the "reserve ratio" is shown in the balance sheet below:

| Example 2: ANZ National Bank Limited Balance Sheet as at 30 September 2007[citation needed] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Assets | NZ$m | Liabilities | NZ$m |

| Cash | 201 | Demand deposits | 25,482 |

| Balance with Central Bank | 2,809 | Term deposits and other borrowings | 35,231 |

| Other liquid assets | 1,797 | Due to other financial institutions | 3,170 |

| Due from other financial institutions | 3,563 | Derivative financial instruments | 4,924 |

| Trading securities | 1,887 | Payables and other liabilities | 1,351 |

| Derivative financial instruments | 4,771 | Provisions | 165 |

| Available for sale assets | 48 | Bonds and notes | 14,607 |

| Net loans and advances | 87,878 | Related party funding | 2,775 |

| Shares in controlled entities | 206 | [subordinated] Loan capital | 2,062 |

| Current tax assets | 112 | Total Liabilities | 99,084 |

| Other assets | 1,045 | Share capital | 5,943 |

| Deferred tax assets | 11 | [revaluation] Reserves | 83 |

| Premises and equipment | 232 | Retained profits | 2,667 |

| Goodwill and other intangibles | 3,297 | Total Equity | 8,703 |

| Total Assets | 107,787 | Total Liabilities plus Net Worth | 107,787 |

In this example the cash reserves held by the bank is NZ$3,010m (NZ$201m Cash + NZ$2,809m Balance at Central Bank) and the Demand Deposits (liabilities) of the bank are NZ$25,482m, for a cash reserve ratio of 11.81%.

Other financial ratios

The key financial ratio used to analyze fractional-reserve banks is the cash reserve ratio, which is the ratio of cash reserves to demand deposits. However, other important financial ratios are also used to analyze the bank's liquidity, financial strength, profitability etc.

For example the ANZ National Bank Limited balance sheet above gives the following financial ratios:

- The cash reserve ratio is $3,010m/$25,482m, i.e. 11.81%.

- The liquid assets reserve ratio is ($201m+$2,809m+$1,797m)/$25,482m, i.e. 18.86%.

- The equity capital ratio is $8,703m/107,787m, i.e. 8.07%.

- The tangible equity ratio is ($8,703m-$3,297m)/107,787m, i.e. 5.02%

- The total capital ratio is ($8,703m+$2,062m)/$107,787m, i.e. 9.99%.

It is very important how the term 'reserves' is defined for calculating the reserve ratio, as different definitions give different results. Other important financial ratios may require analysis of disclosures in other parts of the bank's financial statements. In particular, for liquidity risk, disclosures are incorporated into a note to the financial statements that provides maturity analysis of the bank's assets and liabilities and an explanation of how the bank manages its liquidity.

How the example bank manages its liquidity

The ANZ National Bank Limited explains its methods as:[citation needed]

Liquidity risk is the risk that the Banking Group will encounter difficulties in meeting commitments associated with its financial liabilities, e.g. overnight deposits, current accounts, and maturing deposits; and future commitments e.g. loan draw-downs and guarantees. The Banking Group manages its exposure to liquidity risk by maintaining sufficient liquid funds to meet its commitments based on historical and forecast cash flow requirements.

The following maturity analysis of assets and liabilities has been prepared on the basis of the remaining period to contractual maturity as at the balance date. The majority of longer term loans and advances are housing loans, which are likely to be repaid earlier than their contractual terms. Deposits include substantial customer deposits that are repayable on demand. However, historical experience has shown such balances provide a stable source of long term funding for the Banking Group. When managing liquidity risks, the Banking Group adjusts this contractual profile for expected customer behaviour.

| Example 2: ANZ National Bank Limited Maturity Analysis of Assets and Liabilities as at 30 September 2007[citation needed] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Carrying Value |

< 3 Months |

3–12 Months |

1–5 Years |

5+ Years |

No Specified Maturity | |

| Assets | ||||||

| Liquid assets | 4,807 | 4,807 | ||||

| Due from other financial institutions | 3,563 | 2,650 | 440 | 187 | 286 | |

| Derivative financial instruments | 4,711 | 4,711 | ||||

| Assets available for sale | 48 | 33 | 1 | 13 | 1 | |

| Net loans and advances | 87,878 | 9,276 | 9,906 | 24,142 | 44,905 | |

| Other assets | 4,903 | 970 | 179 | 3,754 | ||

| Total Assets | 107,787 | 18,394 | 10,922 | 25,013 | 45,343 | 8,115 |

| Liabilities | ||||||

| Due to other financial institutions | 3,170 | 2,356 | 405 | 32 | 377 | |

| Deposits and other borrowings | 70,030 | 53,059 | 14,726 | 2,245 | ||

| Derivative financial instruments | 4,932 | 4,932 | ||||

| Other liabilities | 1,516 | 1,315 | 96 | 32 | 60 | 13 |

| Bonds and notes | 14,607 | 672 | 4,341 | 9,594 | ||

| Related party funding | 2,275 | 2,275 | ||||

| Loan capital | 2,062 | 100 | 1,653 | 309 | ||

| Total Liabilities | 99,084 | 60,177 | 19,668 | 13,556 | 746 | 4,937 |

| Net liquidity gap (Total Assets less Total Liabilities) | 8,703 | (41,783) | (8,746) | 11,457 | 44,597 | 3,178 |

| Net Liquidity Gap – Cumulative | 8,703 | (41,783) | (50,529) | (39,072) | 5,525 | 8,703 |

Criticisms of standard textbook descriptions of fractional reserve banking

Some economists, including a former governor of the Bank of England, dispute the standard textbook descriptions of fractional-reserve banking.[22][23][24][25][26] For example, Lord Adair Turner, formally the UK's chief financial regulator, said "Banks do not, as too many textbooks still suggest, take deposits of existing money from savers and lend it out to borrowers: they create credit and money ex nihilo – extending a loan to the borrower and simultaneously crediting the borrower’s money account".[27]

Criticisms of fractional reserve banking

In 1935, economist Irving Fisher proposed a system of 100% reserve banking as a means of reversing the deflation of the Great depression. He wrote: "100 per cent banking [...] would give the Federal Reserve absolute control over the money supply. Recall that under the present fractional reserve system of depository institutions, the money supply is determined in the short run by such non-policy variables as the currency/deposit ratio of the public and the excess reserve ratio of depository institutions."[28]

Milton Friedman said "Our present fractional reserve banking system has two major defects. First, it involves extensive governmental intervention into lending and investing activities that should preferably be left to the free market. Second, decisions by holders of money about the form in which they want to hold money and by banks about the structure of their assets tend to affect the amount available to lend. This has often been referred to as the 'inherent instability' of a fractional reserve system". In a book he wrote in which he proposed that fractional reserve banking should be abolished and replaced with full reserve banking. [29] In his review in the American Economic Review, economist Lawrence Ritter wrote that Friedman's argument is unconvincing and his evidence unsatisfactory.[30]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Abel, Andrew; Bernanke, Ben (2005). "14.1". Macroeconomics (5th ed.). Pearson. pp. 522–532

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Mankiw, N. Gregory (2002). "Chapter 18: Money Supply and Money Demand". Macroeconomics (5th ed.). Worth. pp. 482–489

- ↑ Frederic S. Mishkin, Economics of Money, Banking and Financial Markets, 10th Edition. Prentice Hall 2012

- ↑ Carl Menger: Principles of Economics

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 United States. Congress. House. Banking and Currency Committee. (1964). Money facts; 169 questions and answers on money – a supplement to A Primer on Money, with index, Subcommittee on Domestic Finance ... 1964.. Washington D.C.

- ↑ Charles P. Kindleberger, A Financial History of Western Europe. Routledge 2007

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 The Federal Reserve in Plain English – An easy-to-read guide to the structure and functions of the Federal Reserve System. See page 5 of the document for the purposes and functions: http://www.frbsf.org/publications/education/plainenglish/index.html

- ↑ Abel, Andrew; Bernanke, Ben (2005). "7". Macroeconomics (5th ed.). Pearson. pp. 266–269.

- ↑ Maturity Transformation Brad DeLong

- ↑ Mankiw, N. Gregory (2002). "9". Macroeconomics (5th ed.). Worth. pp. 238–255.

- ↑ Page 57 of 'The FED today', a publication on an educational site affiliated with the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, designed to educate people on the history and purpose of the United States Federal Reserve system. The FED today Lesson 6

- ↑ "Mervyn King, Finance: A Return from Risk". Bank of England. " Banks are dangerous institutions. They borrow short and lend long. They create liabilities which promise to be liquid and hold few liquid assets themselves. That though is hugely valuable for the rest of the economy. Household savings can be channelled to finance illiquid investment projects while providing access to liquidity for those savers who may need it.... If a large number of depositors want liquidity at the same time, banks are forced into early liquidation of assets – lowering their value ...'"

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Bank for International Settlements – The Role of Central Bank Money in Payment Systems. See page 9, titled, "The coexistence of central and commercial bank monies: multiple issuers, one currency": http://www.bis.org/publ/cpss55.pdf

A quick quotation in reference to the 2 different types of money is listed on page 3. It is the first sentence of the document:

- "Contemporary monetary systems are based on the mutually reinforcing roles of central bank money and commercial bank monies."

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 European Central Bank – Domestic payments in Euroland: commercial and central bank money:

http://www.ecb.int/press/key/date/2000/html/sp001109_2.en.html One quotation from the article referencing the two types of money:

- "At the beginning of the 20th almost the totality of retail payments were made in central bank money. Over time, this monopoly came to be shared with commercial banks, when deposits and their transfer via cheques and giros became widely accepted. Banknotes and commercial bank money became fully interchangeable payment media that customers could use according to their needs. While transaction costs in commercial bank money were shrinking, cashless payment instruments became increasingly used, at the expense of banknotes"

- ↑ Macmillan report 1931 account of how fractional banking works http://books.google.ca/books?hl=en&id=EkUTaZofJYEC&dq=British+Parliamentary+reports+on+international+finance&printsec=frontcover&source=web&ots=kHxssmPNow&sig=UyopnsiJSHwk152davCIyQAMVdw&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=1&ct=result#PPA34,M1

- ↑ http://www.mhhe.com/economics/mcconnell15e/graphics/mcconnell15eco/common/dothemath/moneymultiplier.html

- ↑ http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h3/Current/ Federal Reserve Board, "AGGREGATE RESERVES OF DEPOSITORY INSTITUTIONS AND THE MONETARY BASE" (Updated weekly).

- ↑ http://books.google.com/books?id=FdrbugYfKNwC&pg=PA169&lpg=PA169&dq=united+states+money+multiplier&source=web&ots=C_Hw1u82xe&sig=m7g0bMz167DijFsOCbn5f4aWAOU#PPA170,M1 Bruce Champ & Scott Freeman, Modeling Monetary Economies, p. 170 (Figure 9.1).

- ↑ http://books.google.com/books?id=I-49pxHxMh8C&pg=PA303&dq=deposit+reserves&lr=&sig=hMQtESrWP6IBRYiiaZgKwIoDWVk#PPA295,M1 William MacEachern, Macroeconomics: A Contemporary Introduction, p. 295

- ↑ ebook: The Federal Reserve – Purposes and Functions:http://www.federalreserve.gov/pf/pf.htm

- see pages 13 and 14 of the pdf version for information on government regulations and supervision over banks

- ↑ Reserve Bank of India – Report on Currency and Finance 2004–05 (See page 71 of the full report or just download the section Functional Evolution of Central Banking): http://www.rbi.org.in/scripts/AnnualPublications.aspx?head=Report%20on%20Currency%20and%20Finance&fromdate=03/17/06&todate=03/19/06: The monopoly power to issue currency is delegated to a central bank in full or sometimes in part. The practice regarding the currency issue is governed more by convention than by any particular theory. It is well known that the basic concept of currency evolved in order to facilitate exchange. The primitive currency note was in reality a promissory note to pay back to its bearer the original precious metals. With greater acceptability of these promissory notes, these began to move across the country and the banks that issued the promissory notes soon learnt that they could issue more receipts than the gold reserves held by them. This led to the evolution of the fractional-reserve system. It also led to repeated bank failures and brought forth the need to have an independent authority to act as lender-of-the-last-resort. Even after the emergence of central banks, the concerned governments continued to decide asset backing for issue of coins and notes. The asset backing took various forms including gold coins, bullion, foreign exchange reserves and foreign securities. With the emergence of a fractional-reserve system, this reserve backing (gold, currency assets, etc.) came down to a fraction of total currency put in circulation.

- ↑ Sheard, Paul. "Repeat After Me: Banks Cannot And Do Not "Lend Out" Reserves". Standard and Poor's.

- ↑ King, Mervyn. "The transmission mechanism of monetary policy". Bank of England.

- ↑ Goodhart, Charles. "Money, credit and bank behaviour: need for a new approach".

- ↑ Carpenter, Seth. "Money, Reserves, and the Transmission of Monetary Policy: Does the Money Multiplier Exist?".

- ↑ Tobin, James. "Commercial Banks as Creators of "Money"".

- ↑ Turner, Adair. "Credit Money and Leverage, what Wicksell, Hayek and Fisher knew and modern macroeconomics forgot".

- ↑ Fisher, Irving (1997). 100% Money. Pickering & Chatto Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85196-236-5.

- ↑ Friedman, Milton (1992). A Program For Monetary Stability. p. 66.

- ↑ Lawrence S. Ritter The American Economic Review Vol. 50, No. 4 (September, 1960) pp. 765-768

Further reading

- Crick, W.F. (1927), The genesis of bank deposits, Economica, vol 7, 1927, pp 191–202.

- Friedman, Milton (1960), A Program for Monetary Stability, New York, Fordham University Press.

- Meigs, A.J. (1962), Free reserves and the money supply, Chicago, University of Chicago, 1962.

- Paul, Ron (2009). "2 The Origin and Nature of the Fed". End the Fed. New York: Grand Central Publishing. ISBN 978-0-446-54919-6.

- Philips, C.A. (1921), Bank Credit, New York, Macmillan, chapters 1–4, 1921,

- Thomson, P. (1956), Variations on a theme by Philips, American Economic Review vol 46, December 1956, pp. 965–970.

External links

- Regulation D of the Federal Reserve Board of the U.S.

- Interactive Fractional-Reserve Calculator Calculator that details deposit multiplication for any reserve requirement.

- Federalreserveeducation.org – The Principle of Multiple Deposit Creation

- Reserve Requirements – Fedpoints – Federal Reserve Bank of New York

- Bank for International Settlements – The Role of Central Bank Money in Payment Systems