Forensic science

| Forensic science |

|---|

|

| Physiological sciences |

|

| Social sciences |

| Forensic criminalistics |

| Digital forensics |

|

| Related disciplines |

| People |

| Related articles |

Forensic science is the scientific method of gathering and examining information about the past. This is especially important in law enforcement where forensics is done in relation to criminal or civil law,[1] but forensics are also carried out in other fields, such as astronomy, archaeology, biology and geology to investigate ancient times.

In the United States there are over 12,000 forensic science technicians, as of 2010.[2]

The word forensic comes from the Latin forēnsis, meaning "of or before the forum."[3] In Roman times, a criminal charge meant presenting the case before a group of public individuals in the forum. Both the person accused of the crime and the accuser would give speeches based on their sides of the story. The individual with the best argument and delivery would determine the outcome of the case. This origin is the source of the two modern usages of the word forensic – as a form of legal evidence and as a category of public presentation. In modern use, the term "forensics" in the place of "forensic science" can be considered correct as the term "forensic" is effectively a synonym for "legal" or "related to courts". However, the term is now so closely associated with the scientific field that many dictionaries include the meaning that equates the word "forensics" with "forensic science".

History

Early methods

The ancient world lacked standardized forensic practices, which aided criminals in escaping punishment. Criminal investigations and trials relied on forced confessions and witness testimony. However ancient sources do contain several accounts of techniques that foreshadow concepts in forensic science that were developed centuries later.[4]

For instance, Archimedes (287–212 BC) invented a method for determining the volume of an object with an irregular shape. According to Vitruvius, a votive crown for a temple had been made for King Hiero II, who had supplied the pure gold to be used, and Archimedes was asked to determine whether some silver had been substituted by the dishonest goldsmith.[5] Archimedes had to solve the problem without damaging the crown, so he could not melt it down into a regularly shaped body in order to calculate its density. Instead he used the law of displacement to prove that the goldsmith had taken some of the gold and substituted silver instead.

The first written account of using medicine and entomology to solve criminal cases is attributed to the book of Xi Yuan Lu (translated as Washing Away of Wrongs[6][7]), written during the Song Dynasty China by Song Ci (宋慈, 1186–1249) in 1248. In one of the accounts, the case of a person murdered with a sickle was solved by an investigator who instructed everyone to bring his sickle to one location. (He realized it was a sickle by testing various blades on an animal carcass and comparing the wound.) Flies, attracted by the smell of blood, eventually gathered on a single sickle. In light of this, the murderer confessed. The book also offered advice on how to distinguish between a drowning (water in the lungs) and strangulation (broken neck cartilage), along with other evidence from examining corpses on determining if a death was caused by murder, suicide or an accident.

Methods from around the world involved saliva and examination of the mouth and tongue to determine innocence or guilt. In ancient Chinese cultures, sometimes suspects were made to fill their mouths with dried rice and spit it back out. In ancient middle-eastern cultures the accused were made to lick hot metal rods briefly. Both of these tests had some validity[citation needed] since a guilty person would produce less saliva and thus have a drier mouth. The accused were considered guilty if rice was sticking to their mouth in abundance or if their tongues were severely burned due to lack of shielding from saliva.

Origins of forensic science

In the 16th-century Europe medical practitioners in army and university settings began to gather information on the cause and manner of death. Ambroise Paré, a French army surgeon, systematically studied the effects of violent death on internal organs. Two Italian surgeons, Fortunato Fidelis and Paolo Zacchia, laid the foundation of modern pathology by studying changes that occurred in the structure of the body as the result of disease. In the late 18th century, writings on these topics began to appear. These included A Treatise on Forensic Medicine and Public Health by the French physician Fodéré and The Complete System of Police Medicine by the German medical expert Johann Peter Frank.

As the rational values of the Enlightenment era increasingly permeated society in the 18th century, criminal investigation became a more evidence-based, rational procedure - the use of torture to force confessions was curtailed and belief in witchcraft and other powers of the occult largely ceased to influence the court's decisions. Two examples of English forensic science in individual legal proceedings demonstrate the increasing use of logic and procedure in criminal investigations at the time. In 1784, in Lancaster, John Toms was tried and convicted for murdering Edward Culshaw with a pistol. When the dead body of Culshaw was examined, a pistol wad (crushed paper used to secure powder and balls in the muzzle) found in his head wound matched perfectly with a torn newspaper found in Toms' pocket, leading to the latter's conviction.

In Warwick in 1816, a farm labourer was tried and convicted of the murder of a young maidservant. She had been drowned in a shallow pool and bore the marks of violent assault. The police found footprints and an impression from corduroy cloth with a sewn patch in the damp earth near the pool. There were also scattered grains of wheat and chaff. The breeches of a farm labourer who had been threshing wheat nearby were examined and corresponded exactly to the impression in the earth near the pool.[8]

Toxicology and ballistics

A method for detecting arsenous oxide, simple arsenic, in corpses was devised in 1773 by the Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele. His work was expanded, in 1806, by German chemist Valentin Ross, who learned to detect the poison in the walls of a victim's stomach.

James Marsh was the first to apply this new science to the art of forensics. He was called by the prosecution in a murder trial to give evidence as a chemist in 1832. The defendant, John Bodle, was accused of poisoning his grandfather with arsenic-laced coffee. Marsh performed the standard test by mixing a suspected sample with hydrogen sulfide and hydrochloric acid. While he was able to detect arsenic as yellow arsenic trisulfide, when it came to show it to the jury it had deteriorated, allowing the suspect to be acquitted due to reasonable doubt.

Annoyed by this, Marsh developed a much better test. He combined a sample containing arsenic with sulfuric acid and arsenic-free zinc, resulting in arsine gas. The gas was ignited, and it decomposed to pure metallic arsenic which, when passed to a cold surface, would appear as a silvery-black deposit.[9] So sensitive was the test that it could detect as little as one-fiftieth of a milligram of arsenic. He first described this test in The Edinburgh Philosophical Journal in 1836.[10]

Henry Goddard at Scotland Yard pioneered the use of bullet comparison in 1835. He noticed a flaw in the bullet that killed the victim, and was able to trace this back to the mold that was used in the manufacturing process.[11]

Anthropometry

The French police officer, Alphonse Bertillon was the first to apply the anthropological technique of anthropometry to law enforcement, thereby creating an identification system based on physical measurements. Before that time, criminals could only be identified by name or photograph.[12][13] Dissatisfied with the ad hoc methods used to identify captured criminals in France in the 1870s, he began his work on developing a reliable system of anthropometrics for human classification.[14]

Bertillon created many other forensics techniques, including forensic document examination, the use of galvanoplastic compounds to preserve footprints, ballistics, and the dynamometer, used to determine the degree of force used in breaking and entering. Although his central methods were soon to be supplanted by fingerprinting, "his other contributions like the mug shot and the systematization of crime-scene photography remain in place to this day."[15]

Fingerprints

Sir William Herschel was one of the first to advocate the use of fingerprinting in the identification of criminal suspects. While working for the Indian Civil Service, he began to use thumbprints on documents as a security measure to prevent the then-rampant repudiation of signatures in 1858.[16]

In 1877 at Hooghly (near Calcutta) he instituted the use of fingerprints on contracts and deeds and he registered government pensioners' fingerprints to prevent the collection of money by relatives after a pensioner's death.[17] Herschel also fingerprinted prisoners upon sentencing to prevent various frauds that were attempted in order to avoid serving a prison sentence.

In 1880, Dr. Henry Faulds, a Scottish surgeon in a Tokyo hospital, published his first paper on the subject in the scientific journal Nature, discussing the usefulness of fingerprints for identification and proposing a method to record them with printing ink. He established their first classification and was also the first to identify fingerprints left on a vial.[18] Returning to the UK in 1886, he offered the concept to the Metropolitan Police in London but it was dismissed at that time.[19]

Faulds wrote to Charles Darwin with a description of his method but, too old and ill to work on it, Darwin gave the information to his cousin, Francis Galton, who was interested in anthropology. Having been thus inspired to study fingerprints for ten years, Galton published a detailed statistical model of fingerprint analysis and identification and encouraged its use in forensic science in his book Finger Prints. He had calculated that the chance of a "false positive" (two different individuals having the same fingerprints) was about 1 in 64 billion.[20]

Juan Vucetich, an Argentine chief police officer, created the first method of recording the fingerprints of individuals on file. In 1892, after studying Galton's pattern types, Vucetich set up the world's first fingerprint bureau. In that same year, Francisca Rojas of Necochea, was found in a house with neck injuries, whilst her two sons were found dead with their throats cut. Rojas accused a neighbour, but despite brutal interrogation, this neighbour would not confess to the crimes. Inspector Alvarez, a colleague of Vucetich, went to the scene and found a bloody thumb mark on a door. When it was compared with Rojas' prints, it was found to be identical with her right thumb. She then confessed to the murder of her sons.

A Fingerprint Bureau was established in Calcutta (Kolkata), India, in 1897, after the Council of the Governor General approved a committee report that fingerprints should be used for the classification of criminal records. Working in the Calcutta Anthropometric Bureau, before it became the Fingerprint Bureau, were Azizul Haque and Hem Chandra Bose. Haque and Bose were Indian fingerprint experts who have been credited with the primary development of a fingerprint classification system eventually named after their supervisor, Sir Edward Richard Henry.[21][22] The Henry Classification System, co-devised by Haque and Bose, was accepted in England and Wales when the first United Kingdom Fingerprint Bureau was founded in Scotland Yard, the Metropolitan Police headquarters, London, in 1901. Sir Edward Richard Henry subsequently achieved improvements in dactyloscopy.

In the United States, Dr. Henry P. DeForrest used fingerprinting in the New York Civil Service in 1902, and by 1906, New York City Police Department Deputy Commissioner Joseph A. Faurot, an expert in the Bertillon system and a finger print advocate at Police Headquarters, introduced the fingerprinting of criminals to the United States.

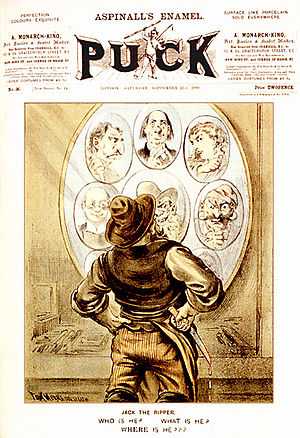

Maturation

By the turn of the 20th century, the science of forensics had become largely established in the sphere of criminal investigation. Scientific and surgical investigation was widely employed by the Metropolitan Police during their pursuit of the mysterious Jack the Ripper, who killed a series of prostitutes in the 1880s. This case is a watershed in the application of forensic science. Large teams of policemen conducted house-to-house inquiries throughout Whitechapel. Forensic material was collected and examined. Suspects were identified, traced and either examined more closely or eliminated from the inquiry. Police work follows the same pattern today.[23] Over 2000 people were interviewed, "upwards of 300" people were investigated, and 80 people were detained.[24]

The investigation was initially conducted by the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) headed by Detective Inspector Edmund Reid. Later, Detective Inspectors Frederick Abberline, Henry Moore, and Walter Andrews were sent from Central Office at Scotland Yard to assist. Initially, butchers, surgeons and physicians were suspected because of the manner of the mutilations. The alibis of local butchers and slaughterers were investigated, with the result that they were eliminated from the inquiry.[25] Some contemporary figures thought the pattern of the murders indicated that the culprit was a butcher or cattle drover on one of the cattle boats that plied between London and mainland Europe. Whitechapel was close to the London Docks,[26] and usually such boats docked on Thursday or Friday and departed on Saturday or Sunday.[27] The cattle boats were examined but the dates of the murders did not coincide with a single boat's movements and the transfer of a crewman between boats was also ruled out.[28]

At the end of October, Robert Anderson asked police surgeon Thomas Bond to give his opinion on the extent of the murderer's surgical skill and knowledge.[29] The opinion offered by Bond on the character of the "Whitechapel murderer" is the earliest surviving offender profile.[30] Bond's assessment was based on his own examination of the most extensively mutilated victim and the post mortem notes from the four previous canonical murders.[31] In his opinion the killer must have been a man of solitary habits, subject to "periodical attacks of homicidal and erotic mania", with the character of the mutilations possibly indicating "satyriasis".[31] Bond also stated that "the homicidal impulse may have developed from a revengeful or brooding condition of the mind, or that religious mania may have been the original disease but I do not think either hypothesis is likely".[31]

Handbook for Coroners, police officials, military policemen was written by the Austrian criminal jurist Hans Gross in 1893, and is generally acknowledged as the birth of the field of criminalistics. The work combined in one system fields of knowledge that had not been previously integrated, such as psychology and science, and which could be successfully used against crime. Gross adapted some fields to the needs of criminal investigation, such as crime scene photography. He went on to found the Institute of Criminalistics in 1912, as part of the University of Graz' Law School. This Institute was followed by many similar institutes all over the world.[32]

In 1909, Archibald Reiss founded the Institut de police scientifique of the University of Lausanne (UNIL), the first school of forensic science in the world. Dr. Edmond Locard, became known as the "Sherlock Holmes of France". He formulated the basic principle of forensic science: "Every contact leaves a trace", which became known as Locard's exchange principle. In 1910, he founded what may have been the first criminal laboratory in the world, after persuading the Police Department of Lyon (France) to give him two attic rooms and two assistants.[33]

Symbolic of the new found prestige of forensics and the use of reasoning in detective work was the popularity of the fictional character Sherlock Holmes, written by Arthur Conan Doyle in the late 19th century. He remains a great inspiration for forensic science, especially for the way his acute study of a crime scene yielded small clues as to the precise sequence of events. He made great use of trace evidence such as shoe and tire impressions, as well as fingerprints, ballistics and handwriting analysis, now known as questioned document examination.[34] Such evidence is used to test theories conceived by the police, for example, or by the investigator himself.[35] All of the techniques advocated by Holmes later became reality, but were generally in their infancy at the time Conan Doyle was writing. In many of his reported cases, Holmes frequently complains of the way the crime scene has been contaminated by others, especially by the police, emphasising the critical importance of maintaining its integrity, a now well-known feature of crime scene examination. He used analytical chemistry for blood residue analysis as well as toxicology examination and determination for poisons. He used ballistics by measuring bullet calibres and matching them with a suspected murder weapon.[36]

20th century

Later in the 20th century several British pathologists, Bernard Spilsbury, Francis Camps, Sydney Smith and Keith Simpson pioneered new forensic science methods. Alec Jeffreys pioneered the use of DNA profiling in forensic science in 1984. He realized the scope of DNA fingerprinting, which uses variations in the genetic code to identify individuals. The method has since become important in forensic science to assist police detective work, and it has also proved useful in resolving paternity and immigration disputes.[37] DNA fingerprinting was first used as a police forensic test to identify the rapist and killer of two teenagers, Lynda Mann and Dawn Ashworth, who were both murdered in Narborough, Leicestershire, in 1983 and 1986 respectively. Colin Pitchfork was identified and convicted of murder after samples taken from him matched semen samples taken from the two dead girls.

Forensic science has been fostered by a number of national forensic science learned bodies including the American Academy of Forensic Sciences (founded 1948), publishers of the Journal of Forensic Sciences;[38] the Canadian Society of Forensic Science (founded 1953), publishers of the Journal of the Canadian Society of Forensic Science; the British Academy of Forensic Sciences[39] (founded 1960), publishers of Medicine, science and the law,[40] and the Australian Academy of Forensic Sciences (founded 1967), publishers of the Australian Journal of Forensic Sciences.[41]

Subdivisions

- Art forensics concerns the art authentication cases to help research the work's authenticity. Art authentication methods are used to detect and identify forgery, faking and copying of art works, e.g. paintings.

- Computational forensics concerns the development of algorithms and software to assist forensic examination.

- Criminalistics is the application of various sciences to answer questions relating to examination and comparison of biological evidence, trace evidence, impression evidence (such as fingerprints, footwear impressions, and tire tracks), controlled substances, ballistics, firearm and toolmark examination, and other evidence in criminal investigations. In typical circumstances evidence is processed in a Crime lab.

- Digital forensics is the application of proven scientific methods and techniques in order to recover data from electronic / digital media. Digital Forensic specialists work in the field as well as in the lab.

- Forensic accounting is the study and interpretation of accounting evidence

- Forensic aerial photography is the study and interpretation of aerial photographic evidence

- Forensic anthropology is the application of physical anthropology in a legal setting, usually for the recovery and identification of skeletonized human remains.

- Forensic archaeology is the application of a combination of archaeological techniques and forensic science, typically in law enforcement.

- Forensic astronomy uses methods from astronomy to determine past celestial constellations for forensic purposes.

- Forensic botany is the study of plant life in order to gain information regarding possible crimes.

- Forensic chemistry is the study of detection and identification of illicit drugs, accelerants used in arson cases, explosive and gunshot residue.

- Forensic dactyloscopy is the study of fingerprints.

- Forensic document examination or questioned document examination answers questions about a disputed document using a variety of scientific processes and methods. Many examinations involve a comparison of the questioned document, or components of the document, with a set of known standards. The most common type of examination involves handwriting, whereby the examiner tries to address concerns about potential authorship.

- Forensic DNA analysis takes advantage of the uniqueness of an individual's DNA to answer forensic questions such as paternity/maternity testing and placing a suspect at a crime scene, e.g. in a rape investigation.

- Forensic engineering is the scientific examination and analysis of structures and products relating to their failure or cause of damage.

- Forensic entomology deals with the examination of insects in, on and around human remains to assist in determination of time or location of death. It is also possible to determine if the body was moved after death using entomology.

- Forensic geology deals with trace evidence in the form of soils, minerals and petroleum.

- Forensic geophysics is the application of geophysical techniques such as radar for detecting objects hidden underground or underwater.[42]

- Forensic intelligence process starts with the collection of data and ends with the integration of results within into the analysis of crimes under investigation[43]

- Forensic Interviews are conducted using the science of professionally using expertise to conduct a variety of investigative interviews with victims, witnesses, suspects or other sources to determine the facts regarding suspicions, allegations or specific incidents in either public or private sector settings.

- Forensic limnology is the analysis of evidence collected from crime scenes in or around fresh-water sources. Examination of biological organisms, in particular diatoms, can be useful in connecting suspects with victims.

- Forensic linguistics deals with issues in the legal system that requires linguistic expertise.

- Forensic meteorology is a site-specific analysis of past weather conditions for a point of loss.

- Forensic odontology is the study of the uniqueness of dentition, better known as the study of teeth.

- Forensic optometry is the study of glasses and other eye wear relating to crime scenes and criminal investigations

- Forensic pathology is a field in which the principles of medicine and pathology are applied to determine a cause of death or injury in the context of a legal inquiry.

- Forensic podiatry is an application of the study of feet footprint or footwear and their traces to analyze scene of crime and to establish personal identity in forensic examinations.

- Forensic psychiatry is a specialized branch of psychiatry as applied to and based on scientific criminology.

- Forensic psychology is the study of the mind of an individual, using forensic methods. Usually it determines the circumstances behind a criminal's behavior.

- Forensic seismology is the study of techniques to distinguish the seismic signals generated by underground nuclear explosions from those generated by earthquakes.

- Forensic serology is the study of the body fluids.[44]

- Forensic toxicology is the study of the effect of drugs and poisons on/in the human body.

- Forensic video analysis is the scientific examination, comparison and evaluation of video in legal matters.

- Mobile device forensics is the scientific examination and evaluation of evidence found in mobile phones, e.g. Call History and Deleted SMS, and includes SIM Card Forensics

- Trace evidence analysis is the analysis and comparison of trace evidence including glass, paint, fibres and hair.

- Wildlife Forensic Science applies a range of scientific disciplines to legal cases involving non-human biological evidence, to solve crimes such as poaching, animal abuse, and trade in endangered species.

Blood Spatter Analysis is the scientific examination of blood spatter patterns found at a crime scene to reconstruct the events of the crime.

- Forensic Investigation also known as forensic audit is the examination of documents and the interviewing of people to extract evidence.

Education and research

Academic centre of education and research in forensic sciences:

- Europe

- School of Criminal Justice (École des sciences criminelles) of the University of Lausanne (Switzerland)

- School of Forensic and Investigative Sciences of the University of Central Lancashire (United Kingdom)

- Centre for the Forensic Sciences of the University College London (United Kingdom)

- North America

- Forensic science program at the Pennsylvania State University (United States)

Notable forensic scientists

- David R. Ashbaugh (1946–)

- Michael Baden (1934–)

- William M. Bass (1928–)

- Alexandre Beaudoin (1978–)

- Joseph Bell (1837–1911)

- Alphonse Bertillon (1853–1914)

- Sara C. Bisel (1932–1996)

- Francis Camps (1905–1972)

- Brian E. Dalrymple (1947–)

- Wilfrid Derome (1877–1931)

- Ellis R. Kerley (1924–1998)

- Paul L. Kirk (1902–1970)

- Wilton M. Krogman (1903–1987)

- Alexandre Lacassagne (1843–1924)

- Henry C. Lee (1938–)

- Edmond Locard (1877–1966)

- William R. Maples (1937–1997)

- Miklos Nyiszli (1901–1956)

- Albert S. Osborn (1858–1946)

- Skip Palenik (1946–)

- Kathy Reichs (1950–)

- Archibald Reiss (1875-1929)

- Keith Simpson (1907–1985)

- Clyde Snow (1928–)

- Sir Bernard Spilsbury (1877–1947)

- Auguste Ambroise Tardieu (1818–1879)

- Paul Uhlenhuth (1870–1957)

- Cyril Wecht (1931–)

Questionable techniques

Some forensic techniques, believed to be scientifically sound at the time they were used, have turned out later to have much less scientific merit or none.[45] Some such techniques include:

- Comparative bullet-lead analysis was used by the FBI for over four decades, starting with the John F. Kennedy assassination in 1963. The theory was that each batch of ammunition possessed a chemical makeup so distinct that a bullet could be traced back to a particular batch or even a specific box. Internal studies and an outside study by the National Academy of Sciences found that the technique was unreliable, and the FBI abandoned the test in 2005.[46]

- Forensic dentistry has come under fire: in at least two cases bite-mark evidence has been used to convict people of murder who were later freed by DNA evidence. A 1999 study by a member of the American Board of Forensic Odontology found a 63 percent rate of false identifications and is commonly referenced within online news stories and conspiracy websites.[47][48] The study was based on an informal workshop during an ABFO meeting, which many members did not consider a valid scientific setting.[49]

- Scientists have also shown, in recent years, that it is possible to fabricate DNA evidence, thus "undermining the credibility of what has been considered the gold standard of proof in criminal cases".[50]

Litigation science

Litigation science describes analysis or data developed or produced expressly for use in a trial versus those produced in the course of independent research. This distinction was made by the US 9th Circuit Court of Appeals when evaluating the admissibility of experts.[51]

This uses demonstrative evidence, which is evidence created in preparation of trial by attorneys or paralegals.

Examples in popular culture

The Argentinean writer Jorge Luis Borges claims that the police novel genre is inaugurated with Edgar Allan Poe's short story, "The Murders in the Rue Morgue". But it is first Sherlock Holmes, the fictional character created by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle in works produced from 1887 to 1915, who used forensic science as one of his investigating methods. Conan Doyle credited the inspiration for Holmes on his teacher at the medical school of the University of Edinburgh, the gifted surgeon and forensic detective Joseph Bell. Agatha Christie's Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple books and television series glorify too a similar prototype.

Decades later the comic strip Dick Tracy also featured a detective using a considerable number of forensic methods, although sometimes the methods were more fanciful than actually possible.

Barry Allen (alter ego of The Flash) is a forensic scientist for the Central City police department.

Defence attorney Perry Mason occasionally used forensic techniques, both in the novels and television series.

One of the earliest television series to focus on the scientific analysis of evidence was Quincy, M.E. (1976–83, and based loosely on an even earlier Canadian series titled Wojeck), with the title character, a medical examiner working in Los Angeles solving crimes through careful study. The opening theme of each episode featured a clip of the title character, played by Jack Klugman, beginning a lecture to a group of police officers with "Gentlemen, you are about to enter the most fascinating sphere of police work, the world of forensic medicine." Later series with similar premises include Dexter, The Mentalist, CSI, Hawaii Five-0, Cold Case, Bones, Law & Order, Body of Proof, NCIS, Criminal Minds, Silent Witness, Case Closed, Midsomer Murders and Waking the Dead, depict glamorized versions of the activities of 21st-century forensic scientists. Some claim these TV shows have changed individuals' expectations of forensic science, an influence termed the "CSI effect".[52]

Non-fiction TV shows such as Forensic Files, The New Detectives, American Justice, and Dayle Hinman's Body of Evidence have also popularized forensic science.

The Ace Attorney series features forensic science, mainly in Apollo Justice: Ace Attorney and the DS-only case in Phoenix Wright: Ace Attorney.

Controversies

Questions about forensic science, fingerprint evidence and the assumption behind these disciplines have been brought to light in some publications,[53][54] including in the New York Post.[55] The article stated that "No one has proved even the basic assumption: That everyone's fingerprint is unique."[55] The article also stated that "Now such assumptions are being questioned - and with it may come a radical change in how forensic science is used by police departments and prosecutors."[55] Law professor Jessica Gabel said on NOVA that forensic science, "lacks the rigors, the standards, the quality controls and procedures that we find, usually, in science."[56]

On 25 June 2009 the Supreme Court issued a 5-to-4 decision in Melendez-Diaz v. Massachusetts stating that crime laboratory reports may not be used against criminal defendants at trial unless the analysts responsible for creating them give testimony and subject themselves to cross-examination. The Supreme Court cited the National Academies report Strengthening Forensic Science in the United States[57] in their decision. Writing for the majority, Justice Antonin Scalia referred to the National Research Council report in his assertion that "Forensic evidence is not uniquely immune from the risk of manipulation."

In 2009, scientists indicated that it is possible to fabricate DNA evidence therefore suggesting it is possible to falsely accuse or acquit a person or persons using forged evidence.[50]

Although forensic science has greatly enhanced investigators ability to solve crimes, they have limitations and must be scrutinized in and out of the courtroom to avoid wrongful convictions, which have happened.[58]

See also

- American Academy of Forensic Sciences

- Archibald Reiss, founder of the first forensic school in the world (1909)

- Association of Firearm and Tool Mark Examiners

- Australian Academy of Forensic Sciences

- Ballistic fingerprinting

- Bloodstain pattern analysis

- Canadian Identification Society

- Computer forensics

- Crime

- Computational forensics

- Diplomatics (Forensic paleography)

- Edmond Locard, founder of the first forensic laboratory in the world (1910)

- Fingerprint

- Footprints

- Forensic accounting

- Forensic animation

- Forensic anthropology

- Forensic biology

- Forensic chemistry

- Forensic economics

- Forensic engineering

- Forensic entomology

- Forensic facial reconstruction

- Forensic identification

- Forensic linguistics

- Forensic materials engineering

- Forensic photography

- Forensic polymer engineering

- Forensic profiling

- Forensic psychiatry

- Forensic psychology

- Forensic seismology

- Forensic video analysis

- Glove prints

- History of forensic photography

- International Association for Identification

- Questioned document examination

- Retrospective diagnosis

- RSID

- Scenes of Crime Officer

- Sherlock Holmes

- Skid mark

- Trace evidence

- Profiling (information science)

- Wildlife Forensic Science

- Wilfrid Derome, founder of the first forensic laboratory in North America (1914)

Bibliography

- Bartos, Leah, "No Forensic Background? No Problem", ProPublica, April 17, 2012.

- Anil Aggrawal's Internet Journal of Forensic Medicine and Toxicology.

- Crime Science: Methods of Forensic Detection by Joe Nickell and John F. Fischer. University Press of Kentucky, 1999. ISBN 0-8131-2091-8.

- Dead Reckoning: The New Science of Catching Killers by Michael Baden, M.D, former New York City Medical Examiner, and Marion Roach. Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-86758-3.

- Forensic Magazine - Forensicmag.com.

- Forensic Materials Engineering: Case Studies by Peter Rhys Lewis, Colin Gagg, Ken Reynolds. CRC Press, 2004.

- Forensic Science Communications, an open access journal of the FBI.

- Forensic sciences international - An international journal dedicated to the applications of medicine and science in the administration of justice - ISSN: 0379-0738 - Elsevier

- Guide to Information Sources in the Forensic Sciences by Cynthia Holt. Libraries Unlimited, 2006. ISBN 1-59158-221-0.

- Haag, Michael G. and Haag, Lucien C. (2011). Shooting Incident Reconstruction: Second Edition. New York: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-382241-3.

- International Journal of Digital Crime and Forensics (IJDCF)

- Marrone, L. (2011) La scena del crimine. Storia e tecniche dell'investigazione scientifica. Roma, Kappa Edizioni. ISBN 978-88-6514-070-3.

- Marrone, L. (2011) Introduzione alle Scienze forensi. Roma, Kappa Edizioni. ISBN 978-88-6514-077-2.

- Owen, D. (2000) Hidden Evidence; The Story of Forensic Science and how it Helped to Solve 40 of the World's Toughest Crimes Quintet Publishing, London. ISBN 1-86155-278-5.

- Quinche, Nicolas, Crime, Science et Identité. Anthologie des textes fondateurs de la criminalistique européenne (1860–1930). Genève: Slatkine, 2006, 368p.

- Quinche, Nicolas, « Les victimes, les mobiles et le modus operandi du criminaliste suisse R.-A. Reiss. Enquête sur les stratégies discursives d’un expert du crime (1906–1922)" in Revue Suisse d’Histoire, 58, no 4, décembre 2008, pp. 426–444.

- Quinche, Nicolas, « L’ascension du criminaliste Rodolphe Archibald Reiss », in Le théâtre du crime : Rodolphe A. Reiss (1875–1929). Lausanne : Presses polytechniques et universitaires romandes, 2009, pp. 231–250.

- Quinche, Nicolas, « Sur les traces du crime : la naissance de la police scientifique et technique en Europe », in Revue internationale de criminologie et de police technique et scientifique, vol. LXII, no 2, juin 2009, pp. 8–10.

- Quinche, Nicolas, and Margot, Pierre, « Coulier, Paul-Jean (1824–1890) : A precursor in the history of fingermark detection and their potential use for identifying their source (1863) », in Journal of forensic identification (Californie), 60 (2), March–April 2010, pp. 129–134.

- Quinche, Nicolas, "Sur les traces du crime : de la naissance du regard indicial à l’institutionnalisation de la police scientifique et technique en Suisse et en France. L’essor de l’Institut de police scientifique de l’Université de Lausanne". Genève : Slatkine, 2011, 686p., (Coll. Travaux des Universités suisses), (Thèse de doctorat de l’Université de Lausanne).

- Science Against Crime by Stuart Kind and Michael Overman. Doubleday, 1972. ISBN 0-385-09249-0.

- Stanton G (2003). "Underwater Crime Scene Investigations (UCSI), a New Paradigm". In: SF Norton (ed). Diving for Science... 2003. Proceedings of the American Academy of Underwater Sciences (22nd annual Scientific Diving Symposium). Retrieved 2008-06-18.

- Structure Magazine no. 40, "RepliSet: High Resolution Impressions of the Teeth of Human Ancestors" by Debbie Guatelli-Steinberg, Assistant Professor of Biological Anthropology, The Ohio State University and John C. Mitchell, Assistant Professor of Biomaterials and Biomechanics School of Dentistry, Oregon Health and Science University.

- The Internet Journal of Biological Anthropology.

- Wiley Encyclopedia of Forensic Science by Allan Jamieson and Andre Moenssens (eds). John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2009. ISBN 978-0-470-01826-2.

- Wiley Encyclopedia of Forensic Science The online version of the Wiley Encyclopedia of Forensic Science by Allan Jamieson and Andre Moenssens (eds)

- "The Real CSI, PBS Frontline documentary, April 17, 2012.

References

- ↑ "Forensics". TheFreeDictionary.com.

- ↑ U.S. Department of Labor. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational Employment and Wages, May 2011. "19-4092 Forensic Science Technicians". http://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes194092.htm

- ↑ Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (6th ed.), Oxford University Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-19-920687-2

- ↑ Schafer, Elizabeth D. (2008). "Ancient science and forensics". In Ayn Embar-seddon, Allan D. Pass (eds.). Forensic Science. Salem Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-58765-423-7.

- ↑ Vitruvius. "De Architectura, Book IX, paragraphs 9–12, text in English and Latin". University of Chicago. Retrieved 2007-08-30.

- ↑ "Forensics Timeline". Cbsnews.com. Retrieved 2011-12-20.

- ↑ A Brief Background of Forensic Science

- ↑ Kind S, Overman M (1972). Science Against Crime. New York City: Doubleday. pp. 12–13. ISBN 0-385-09249-0.

- ↑ McMuigan, Hugh (1921). An Introduction to Chemical Pharmacology. Philadelphia: P. Blakiston's Son & Co. pp. 396 – 397. Retrieved 2007-12-16.

- ↑ Marsh J. (1836). "Account of a method of separating small quantities of arsenic from substances with which it may be mixed". Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal 21: 229–236.

- ↑ "Ballistics".

- ↑ As reported in, "A Fingerprint Fable: The Will and William West Case". http://www.scafo.org/library/110105.html

- ↑ Kirsten Moana Thompson, Crime Films: Investigating the Scene. London: Wallflower Press (2007): 10

- ↑ Ginzburg, Carlo (1984). "Morelli, Freud, and Sherlock Holmes: Clues and Scientific Method". In Eco, Umberto; Sebeok, Thomas. The Sign of Three: Dupin, Holmes, Peirce. Bloomington, IN: History Workshop, Indiana University Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-253-35235-4. LCCN 82049207. OCLC 9412985.

- ↑ Kirsten Moana Thompson, Crime Films: Investigating the Scene. London: Wallflower Press (2007): 10

- ↑ Herschel, William J (1916). The Origin of Finger-Printing. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1-104-66225-7.

- ↑ Herschel, William James (November 25, 1880). "Skin furrows of the hand". Nature 23 (578): 76. Bibcode:1880Natur..23...76H. doi:10.1038/023076b0.

- ↑ Faulds, Henry (October 28, 1880). "On the skin-furrows of the hand". Nature 22 (574): 605. Bibcode:1880Natur..22..605F. doi:10.1038/022605a0.

- ↑ Reid, Donald L. (2003). "Dr. Henry Faulds - Beith Commemorative Society". Journal of Forensic Identification 53 (2). See also this on-line article on Henry Faulds: Tredoux, Gavan (December 2003). "Henry Faulds: the Invention of a Fingerprinter". galton.org.

- ↑ Galton, Francis (1892). "Finger Prints". London: MacMillan and Co.

- ↑ Tewari, RK; Ravikumar, KV (2000). "History and development of forensic science in India". J. Postgrad Med (46): 303–308.

- ↑ Sodhi, J.S.; Kaur, asjeed (2005). "The forgotten Indian pioneers of finger print science". Current Science 88 (1): 185–191.

- ↑ Canter, David (1994), Criminal Shadows: Inside the Mind of the Serial Killer, London: HarperCollins, pp. 12–13, ISBN 0-00-255215-9

- ↑ Inspector Donald Swanson's report to the Home Office, 19 October 1888, HO 144/221/A49301C, quoted in Begg, Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History, p. 205; Evans and Rumbelow, p. 113; Evans and Skinner, The Ultimate Jack the Ripper Sourcebook, p. 125

- ↑ Inspector Donald Swanson's report to the Home Office, 19 October 1888, HO 144/221/A49301C, quoted in Begg, Jack the Ripper: The Definitive History, p. 206 and Evans and Skinner, The Ultimate Jack the Ripper Sourcebook, p. 125

- ↑ Marriott, John, "The Imaginative Geography of the Whitechapel murders", in Werner, p. 48

- ↑ Rumbelow, p. 93; Daily Telegraph, 10 November 1888, quoted in Evans and Skinner, The Ultimate Jack the Ripper Sourcebook, p. 341

- ↑ Robert Anderson to Home Office, 10 January 1889, 144/221/A49301C ff. 235–6, quoted in Evans and Skinner, The Ultimate Jack the Ripper Sourcebook, p. 399

- ↑ Evans and Rumbelow, pp. 186–187; Evans and Skinner, The Ultimate Jack the Ripper Sourcebook, pp. 359–360

- ↑ Canter, pp. 5–6

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Letter from Thomas Bond to Robert Anderson, 10 November 1888, HO 144/221/A49301C, quoted in Evans and Skinner, The Ultimate Jack the Ripper Sourcebook, pp. 360–362 and Rumbelow, pp. 145–147

- ↑ Green, Martin (1999). Otto Gross, Freudian Psychoanalyst, 1877-1920. Lampeter,: Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 0-7734-8164-8.

- ↑ http://www.apsu.edu/oconnort/3210/3210lect02.htm

- ↑ Alexander Bird (27 June 2006). "Abductive Knowledge and Holmesian Inference". In Tamar Szabo Gendler and John Hawthorne. Oxford studies in epistemology. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-19-928590-7.

- ↑ Matthew Bunson (19 October 1994). Encyclopedia Sherlockiana. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-671-79826-0.

- ↑ Jonathan Smith (1994). Fact and feeling: Baconian science and the nineteenth-Century literary imagination. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-299-14354-1.

- ↑ Newton, Giles (4 February 2004). "Discovering DNA fingerprinting: Sir Alec Jeffreys describes its development". Wellcome Trust. Archived from the original on 15 November 2010. Retrieved 23 December 2007.

- ↑ Journal of Forensic Sciences

- ↑ The British Academy of Forensic Sciences

- ↑ Medicine, science and the law

- ↑ Australian Journal of Forensic Sciences

- ↑ "CSI: Geophysics". Physics.org. Retrieved 2011-12-20.

- ↑ p.611 Jahankhani,Hamid; Watson, David Lilburn; Me, Gianluigi Handbook of Electronic Security and Digital Forensics World Scientific, 2009

- ↑ "Forensic serology". Forensic-medecine.info. Retrieved 2010-06-08.

- ↑ Saks, Michael J.; Faigman, David L. (2008). "Failed forensics: how forensic science lost its way and how it might yet find it". Annual Review of Law and Social Science 4: 149–171. doi:10.1146/annurev.lawsocsci.4.110707.172303.

- ↑ Solomon, John (2007-11-18). "FBI's Forensic Test Full of Holes". The Washington Post. p. A1. Retrieved 2008-03-05.

- ↑ Santos, Fernanda (2007-01-28). "Evidence From Bite Marks, It Turns Out, Is Not So Elementary". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-03-05.

- ↑ McRoberts, Flynn (2004-11-29). "Bite-mark verdict faces new scrutiny". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2008-03-05.

- ↑ McRoberts, Flynn (2004-10-19). "From the start, a faulty science". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Polloack, Andrew. "DNA Evidence Can Be Fabricated, Scientists Show". New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/18/science/18dna.html. August 17, 2009

- ↑ Raloff, Janet (2008-01-19). "Judging Science". Science News. pp. 42 (Vol. 173, No. 3). Archived from the original on 2008-02-28. Retrieved 2008-03-05.

- ↑ Holmgren, Janne A.; Fordham, Judith (January 2011). "The CSI Effect and the Canadian and the Australian Jury". Journal of Forensic Sciences 56 (S1): S63–S71. doi:10.1111/j.1556-4029.2010.01621.x

- ↑ "'Badly Fragmented' Forensic Science System Needs Overhaul". The National Academies. February 18, 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-09.

- ↑ "National Academy of Sciences Finds 'Serious Deficiencies' in Nation's Crime Labs". National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers. February 18, 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 Katherine Ramsland (March 6, 2009). "CSI: Without a clue; A new report forces Police and Judges to rethink forensic science". The New York Post, PostScript. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ↑ Jessica Gabel, lawyer and lecturer from NOVA "Forensics on Trial" http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/tech/forensics-on-trial.html

- ↑ "Strengthening Forensic Science in the United States: A Path Forward". Nap.edu. Retrieved 2010-06-08.

- ↑ Fabiola Carletti (August 21, 2012). "How body parts evidence gets from crime scene to courtroom". CBC News, PostScript. Retrieved 2012-08-21.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Forensic science. |