Folding@home

| |

| Original author(s) | Vijay Pande |

|---|---|

| Developer(s) | Pande laboratory, Sony, Nvidia, ATI, Cauldron Development LLC[1] |

| Initial release | October 1, 2000 |

| Stable release | 7.3.6[2] / February 18, 2013[3] |

| Operating system | Microsoft Windows, OS X, GNU-Linux |

| Platform | Cross-platform |

| Available in | English |

| Type | Distributed computing |

| License | Partially GPL, partially proprietary[4] |

| Website | folding.stanford.edu/home |

Folding@home (FAH or F@h) is a distributed computing project for disease research that simulates protein folding, computational drug design, and other types of molecular dynamics. The project uses the idle processing resources of thousands of personal computers owned by volunteers who have installed the software on their systems. Its primary purpose is to determine the mechanisms of protein folding, which is the process by which proteins reach their final three-dimensional structure, and to examine the causes of protein misfolding. This is of significant academic interest with major implications for medical research into Alzheimer's disease, Huntington's disease, and many forms of cancer, among other diseases. To a lesser extent, Folding@home also tries to predict a protein's final structure and determine how other molecules may interact with it, which has applications in drug design. Folding@home is developed and operated by the Pande laboratory at Stanford University, under the direction of Vijay Pande, and is shared by various scientific institutions and research laboratories across the world.[1]

The project has pioneered the use of GPUs, PlayStation 3s, and Message Passing Interface (used for computing on multi-core processors) for distributed computing and scientific research. The project uses statistical simulation methodology that is a paradigm shift from traditional computational approaches.[5] As part of the client-server network architecture, the volunteered machines each receive pieces of a simulation (work units), complete them, and return them to the project's database servers where the units are compiled into an overall simulation. Volunteers can track their contributions on the Folding@home website, which makes volunteers' participation competitive and encourages long-term involvement.

Folding@home is one of the world's fastest computing systems, with a speed of approximately 18 petaFLOPS: greater than all projects running on the BOINC distributed computing platform. The project was also the world's most powerful computing system until mid-2011. This performance from its large-scale computing network has allowed researchers to run computationally expensive atomic-level simulations of protein folding thousands of times longer than previously achieved. Since its launch on October 1, 2000, the Pande lab has produced 109 scientific research papers as a direct result of Folding@home.[6] Results from the project's simulations agree favorably with experiments.[7][8][9]

Project significance

Proteins are an essential component to many biological functions and participate in virtually all processes within biological cells. They often act as enzymes, performing biochemical reactions including cell signaling, molecular transportation, and cellular regulation. As structural elements, some proteins act as a type of skeleton for cells, and as antibodies, other proteins participate in the immune system. Before a protein can take on these roles, it must fold into a functional three-dimensional structure, a process that often occurs spontaneously and is dependent on interactions within its amino acid sequence and interactions of the amino acids with their surroundings. Protein folding is driven by the search to find the most energetically favorable conformation of the protein, i.e. its native state. Thus, understanding protein folding is critical to understanding what a protein does and how it works, and is considered a "holy grail" of computational biology.[10][11] Despite folding occurring within a crowded cellular environment, it typically proceeds smoothly. However, due to a protein's chemical properties or other factors, proteins may misfold—that is, fold down the wrong pathway and end up misshapen. Unless cellular mechanisms are capable of destroying or refolding such misfolded proteins, they can subsequently aggregate and cause a variety of debilitating diseases.[12] Laboratory experiments studying these processes can be limited in scope and atomic detail, leading scientists to use physics-based computational models that, when complementing experiments, seek to provide a more complete picture of protein folding, misfolding, and aggregation.[13][14]

Due to the complexity of proteins' conformation space—the set of possible shapes a protein can take—and limitations in computational power, all-atom molecular dynamics simulations have been severely limited in the timescales which they can study. While most proteins typically fold in the order of milliseconds,[13][15] before 2010 simulations could only reach nanosecond to microsecond timescales.[7] General-purpose supercomputers have been used to simulate protein folding, but such systems are intrinsically expensive and typically shared among many research groups. Additionally, because the computations in kinetic models are serial in nature, strong scaling of traditional molecular simulations to these architectures is exceptionally difficult.[16][17] Moreover, as protein folding is a stochastic process and can statistically vary over time, it is computationally challenging to use long simulations for comprehensive views of the folding process.[18][19]

Protein folding does not occur in a single step.[12] Instead, proteins spend the majority of their folding time—nearly 96% in some cases[20]—"waiting" in various intermediate conformational states, each a local thermodynamic free energy minimum in the protein's energy landscape. Through a process known as adaptive sampling, these conformations are used by Folding@home as starting points for a set of simulation trajectories. As the simulations discover more conformations, the trajectories are restarted from them, and a Markov state model (MSM) is gradually created from this cyclic process. MSMs are discrete-time master equation models which describe a biomolecule's conformational and energy landscape as a set of distinct structures and the short transitions between them. The adaptive sampling Markov state model approach significantly increases the efficiency of simulation as it avoids computation inside the local energy minimum itself, and is amenable to distributed computing (including on GPUGRID) as it allows for the statistical aggregation of short, independent simulation trajectories.[21] The amount of time it takes to construct a Markov state model is inversely proportional to the number of parallel simulations run, i.e. the number of processors available. In other words, it achieves linear parallelization, leading to an approximately four orders of magnitude reduction in overall serial calculation time. A completed MSM may contain tens of thousands of sample states from the protein's phase space (all the conformations a protein can take on) and the transitions between them. The model illustrates folding events and pathways (i.e. routes) and researchers can later use kinetic clustering to view a coarse-grained representation of the otherwise highly detailed model. They can use these MSMs to reveal how proteins misfold and to quantitatively compare simulations with experiments.[5][18][22]

Between 2000 and 2010, the length of the proteins Folding@home has studied have increased by a factor of four, while its timescales for protein folding simulations have increased by six orders of magnitude.[23] In 2002, Folding@home used Markov state models to complete approximately a million CPU days of simulations over the span of several months,[9] and in 2011, MSMs parallelized another simulation that required an aggregate 10 million CPU hours of computation.[24] In January 2010, Folding@home used MSMs to simulate the dynamics of the slow-folding 32-residue NTL9 protein out to 1.52 milliseconds, a timescale consistent with experimental folding rate predictions but a thousand times longer than previously achieved. The model consisted of many individual trajectories, each two orders of magnitude shorter, and provided an unprecedented level of detail into the protein's energy landscape.[5][7][25] In 2010, Folding@home researcher Gregory Bowman was awarded the Thomas Kuhn Paradigm Shift Award from the American Chemical Society for the development of the open-source MSMBuilder software and for attaining quantitative agreement between theory and experiment.[26][27] For his work, Pande was awarded the 2012 Michael and Kate Bárány Award for Young Investigators for "developing field-defining and field-changing computational methods to produce leading theoretical models for protein and RNA folding"[28] as well as the 2006 Irving Sigal Young Investigator Award for his simulation results which "have stimulated a re-examination of the meaning of both ensemble and single-molecule measurements, making Dr. Pande's efforts pioneering contributions to simulation methodology."[29]

Biomedical research

Protein misfolding can result in a variety of diseases including Alzheimer's disease, cancer, Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, cystic fibrosis, Huntington's disease, sickle-cell anemia, and type II diabetes.[12][30][31] Cellular infection by viruses such as HIV and influenza also involve folding events on cell membranes.[32] Once protein misfolding is better understood, therapies can be developed that augment cells' natural ability to regulate protein folding. Such therapies include the use of engineered molecules to alter the production of a certain protein, help destroy a misfolded protein, or assist in the folding process.[33] The combination of computational molecular modeling and experimental analysis has the possibility of fundamentally shaping the future of molecular medicine and the rational design of therapeutics,[14] such as expediting and lowering the costs of drug discovery.[34] The goal of the first five years of Folding@home was to make advances in understanding folding, while the current goal is to understand misfolding and related disease, especially Alzheimer's disease.[35]

The simulations run on Folding@home are used in conjunction with laboratory experiments,[18] but researchers can use them to study how folding in vitro differs from folding in native cellular environments. This is advantageous in studying aspects of folding, misfolding, and their relationships to disease that are difficult to observe experimentally. For example, in 2011 Folding@home simulated protein folding inside a ribosomal exit tunnel, to help scientists better understand how natural confinement and crowding might influence the folding process.[36][37] Furthermore, scientists typically employ chemical denaturants to unfold proteins from their stable native state. It is not generally known how the denaturant affects the protein's refolding, and it is difficult to experimentally determine if these denatured states contain residual structures which may influence folding behavior. In 2010, Folding@home used GPUs to simulate the unfolded states of Protein L, and predicted its collapse rate in strong agreement with experimental results.[38]

The Pande lab is part of Stanford University, a non-profit entity, and does not sell the results generated by Folding@home.[39] The large data sets from the project are freely available for other researchers to use upon request and some can be accessed from the Folding@home website.[40][41] The Pande lab has collaborated with other molecular dynamics systems such as the Blue Gene supercomputer,[42] and they share Folding@home's key software with other researchers, so that the algorithms which benefited Folding@home may aid other scientific areas.[40] In 2011 they released the open-source Copernicus software, which is based on Folding@home's MSM and other parallelization techniques and aims to improve the efficiency and scaling of molecular simulations on large computer clusters or supercomputers.[43][44] Summaries of all scientific findings from Folding@home are posted on the Folding@home website after publication.[6]

Alzheimer's disease

Alzheimer's disease is an incurable neurodegenerative disease which most often affects the elderly and accounts for more than half of all cases of dementia. Its exact cause remains unknown, but the disease is identified as a protein misfolding disease. Alzheimer's is associated with toxic aggregations of the amyloid beta (Aβ) peptide, caused by Aβ misfolding and clumping together with other Aβ peptides. These Aβ aggregates then grow into significantly larger senile plaques, a pathological marker of Alzheimer's disease.[45][46][47] Due to the heterogeneous nature of these aggregates, experimental techniques such as X-ray crystallography and NMR have had difficulty characterizing their structures. Moreover, atomic simulations of Aβ aggregation are extremely computationally demanding due to their size and complexity.[48][49]

Preventing Aβ aggregation is a promising approach to the development of therapeutic drugs for Alzheimer's disease, according to Drs. Naeem and Fazili in a literature review article.[50] In 2008, Folding@home simulated the dynamics of Aβ aggregation in atomic detail over timescales of the order of tens of seconds. Previous studies were only able to simulate about 10 microseconds—Folding@home was able to simulate Aβ folding for six orders of magnitude longer than previously possible. Researchers used the results of this study to identify a beta hairpin that was a major source of molecular interactions within the structure.[51] The study helped prepare the Pande lab for future aggregation studies and for further research to find a small peptide which may stabilize the aggregation process.[48]

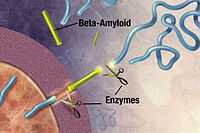

In December 2008, Folding@home found several small drug candidates which appear to inhibit the toxicity of Aβ aggregates.[52] In 2010, in close cooperation with the Center for Protein Folding Machinery, these drug leads began to be tested on biological tissue.[31] In 2011, Folding@home completed simulations of several mutations of Aβ that appear to stabilize the aggregate formation, which could aid in the development of therapeutic drug approaches to the disease and greatly assist with experimental NMR spectroscopy studies of Aβ oligomers.[49][53] Later that year, Folding@home began simulations of various Aβ fragments to determine how various natural enzymes affect the structure and folding of Aβ.[54][55]

Huntington's disease

Huntington's disease is a neurodegenerative genetic disorder that is associated with protein misfolding and aggregation. Excessive repeats of the glutamine amino acid at the N-terminus of the Huntingtin protein cause aggregation, and although the behavior of the repeats is not completely understood, it does lead to the cognitive decline associated with the disease.[56] As with other aggregates, there is difficulty in experimentally determining its structure.[57] Scientists are using Folding@home to study the structure of the Huntingtin protein aggregate and to predict how it forms, assisting with rational drug design approaches to stop the aggregate formation.[31] The N17 fragment of the Huntingtin protein accelerates this aggregation, and while there have been several mechanisms proposed, its exact role in this process remains largely unknown.[58] Folding@home has simulated this and other fragments to clarify their roles in the disease.[59] Since 2008, its drug design approaches for Alzheimer's disease have been applied to Huntington's.[31]

Cancer

More than half of all known cancers involve mutations of p53, a tumor suppressor protein present in every cell which regulates the cell cycle and signals for cell death in the event of damage to DNA. Specific mutations in p53 can disrupt these functions, allowing an abnormal cell to continue growing unchecked, resulting in the development of tumors. Analysis of these mutations helps explain the root causes of p53-related cancers.[60] In 2004, Folding@home was used to perform the first molecular dynamics study of the refolding of p53's protein dimer in an all-atom simulation of water. The simulation's results agreed with experimental observations and gave insights into the refolding of the dimer that were previously unobtainable.[61] This was the first peer reviewed publication on cancer from a distributed computing project.[62] The following year, Folding@home powered a new method to identify the amino acids crucial for the stability of a given protein, which was then used to study mutations of p53. The method was reasonably successful in identifying cancer-promoting mutations and determined the effects of specific mutations which could not otherwise be measured experimentally.[63]

Folding@home is also used to study protein chaperones,[31] heat shock proteins which play essential roles in cell survival by assisting with the folding of other proteins in the crowded and chemically stressful environment within a cell. Rapidly growing cancer cells rely on specific chaperones, and some chaperones play key roles in chemotherapy resistance. Inhibitions to these specific chaperones are seen as potential modes of action for efficient chemotherapy drugs or for reducing the spread of cancer.[64] Using Folding@home and working closely with the Center for Protein Folding Machinery, the Pande lab hopes to find a drug which inhibits those chaperones involved in cancerous cells.[65] Researchers are also using Folding@home to study other molecules related to cancer, such as the enzyme Src kinase and certain forms of the engrailed homeodomain—a large protein which may be involved in many diseases, including cancer.[66][67] In 2011, Folding@home began simulations of the dynamics of the small knottin protein EETI, which can identify carcinomas in imaging scans by binding to surface receptors of cancer cells.[68][69]

Interleukin 2 (IL-2) is a protein that helps T cells of the immune system attack pathogens and tumors. Unfortunately, its use as a cancer treatment is restricted due to serious side effects such as pulmonary edema. IL-2 binds to these pulmonary cells differently than it does to T cells, so IL-2 research involves understanding the differences between these binding mechanisms. In 2012, Folding@home assisted with the discovery of a form of IL-2 which is three hundred times more effective in its immune system role but carries fewer side effects. In experiments, this altered form significantly outperformed natural IL-2 in impeding tumor growth. Pharmaceutical companies have expressed interest in the mutant molecule, and the National Institutes of Health are testing it against a large variety of tumor models in the hopes of accelerating its development as a therapeutic.[70][71]

Osteogenesis imperfecta

Osteogenesis imperfecta, known as brittle bone disease, is an incurable genetic bone disorder which can be lethal. Those with the disease are unable to make functional connective bone tissue. This is most commonly due to a mutation in Type-I collagen,[72] which fulfills a variety of structural roles and is the most abundant protein in mammals.[73] The mutation causes a deformation in collagen's triple helix structure, which if not naturally destroyed, leads to abnormal and weakened bone tissue.[74] In 2005, Folding@home tested a new quantum mechanical technique that improved upon previous simulations methods, and which may be useful for future computational studies of collagen.[75] Although researchers have used Folding@home to study collagen folding and misfolding, the interest stands as a pilot project compared to Alzheimer's and Huntington's research.[31]

Viruses

Folding@home is assisting in research towards preventing certain viruses such as influenza and HIV from recognizing and entering biological cells.[31] In 2011 Folding@home began simulations of the dynamics of the enzyme RNase H, a key component of HIV, in the hopes of designing drugs to deactivate it.[76] Folding@home has also been used to study membrane fusion, an essential event for viral infection and a wide range of biological functions. This fusion involves conformational changes of viral fusion proteins and protein docking,[32] but the exact molecular mechanisms behind fusion remain largely unknown.[77] Fusion events may consist of over a half million atoms interacting for hundreds of microseconds. This complexity limits typical computer simulations to about ten thousand atoms over tens of nanoseconds: a difference of several orders of magnitude.[51] The development of models to predict the mechanisms of membrane fusion will assist in the scientific understanding of how to target the process with antiviral drugs.[78] In 2006 scientists applied Markov state models and the Folding@home network to discover two pathways for fusion and gain other mechanistic insights.[51]

Following detailed simulations from Folding@home of small cells known as vesicles, in 2007 the Pande lab introduced a new computational technique for measuring the topology of its structural changes during fusion.[79] In 2009, researchers used Folding@home to study mutations of influenza hemagglutinin, a protein that attaches a virus to its host cell and assists with viral entry. Mutations to hemagglutinin affect how well the protein binds to a host's cell surface receptor molecules, which determines how infective the virus strain is to the host organism. Knowledge of the effects of hemagglutinin mutations assists in the development of antiviral drugs.[80][81] As of 2012, Folding@home continues to simulate the folding and interactions of hemagglutinin, complementing experimental studies at the University of Virginia.[31][82]

Drug design

Drugs function by binding to specific locations on target molecules and causing a certain desired change, such as disabling the target or causing a conformational change. Ideally, a drug should act very specifically and bind only to its target without interfering with other biological functions. However, it is difficult to precisely determine where and how tightly two molecules will bind. Due to limitations in computational power, current in silico approaches usually have to trade speed for accuracy; e.g. use rapid protein docking methods instead of computationally expensive free energy calculations. Folding@home's computational performance allows researchers to use both techniques, and evaluate their efficiency and reliability.[35][83][84] Computer-assisted drug design has the potential to expedite and lower the costs of drug discovery.[34] In 2010, Folding@home used MSMs and free energy calculations to predict the native state of the villin protein to within 1.8 Å RMSD (root mean square deviation) from the crystalline structure experimentally determined through X-ray crystallography. This accuracy has implications to future protein structure prediction approaches, including for intrinsically unstructured proteins.[51] Scientists have used Folding@home to research drug resistance by studying vancomycin, an antibiotic of "last resort", and beta-lactamase, a protein that can break down antibiotics like penicillin.[85][86]

Chemical activity occurs along a protein's active site. Traditional drug design approaches involve tightly binding to this site and blocking its activity, under the assumption that the target protein exists in a single rigid structure. However, this approach only works for approximately 15% of all proteins. Proteins contain allosteric sites which, when bound to by small molecules, can alter a protein's conformation and ultimately affect the protein's activity. These sites are attractive drug targets, but locating them is very computationally expensive. In 2012, Folding@home and MSMs were used to identify allosteric site in three medically relevant proteins: beta-lactamase, interleukin-2, and RNase H.[86][87]

Approximately half of all known antibiotics interfere with the workings of a bacteria's ribosome, a large and complex biochemical machine that performs protein biosynthesis by translating messenger RNA into proteins. Macrolide antibiotics clog the ribosome's exit tunnel, preventing synthesis of essential bacterial proteins. In 2007 the Pande lab received a grant to study and design new antibiotics.[31] In 2008 they used Folding@home to study the interior of this tunnel and how specific molecules may affect it.[88] The full structure of the ribosome has only been recently determined, and Folding@home has also simulated ribosomal proteins, as many of their functions remain largely unknown.[89]

Participation

In addition to reporting active processors, Folding@home determines its computing performance as measured in floating point operations per second (FLOPS) based on the actual execution time of its calculations. Originally this was reported as native FLOPS: the raw performance from each given type of processing hardware.[90] In March 2009 Folding@home began reporting the performance in native and x86 FLOPS,[91] the latter being an estimation of how many FLOPS the calculation would take on a standard x86 CPU architecture, which is commonly used as a performance reference. Specialized hardware such as GPUs can efficiently perform certain complex functions in a single floating point operation which would otherwise require multiple operations on the x86 architecture. The x86 measurement attempts to even out these hardware differences.[90] Despite conservative conversions, the GPU clients' x86 FLOPS are consistently greater than their native FLOPS and comprise a large majority of Folding@home's measured computing performance.[92][93]

In 2007 Guinness recognized Folding@home as the most powerful distributed computing network.[94] As of September 23, 2013, the project has 472,541 active CPU cores and 29,681 active GPUs for a total of 18.221 x86 petaFLOPS (9.158 native petaFLOPS).[92] At the same time, the combined efforts of all distributed computing projects under BOINC totals 7.369 petaFLOPS.[95] In November 2012 Folding@home updated its accounting of FLOPS, especially for GPUs, and now reports the number of active processor cores as well as physical processors.[96] Using the Markov state model approach, Folding@home achieves strong scaling across its user base and gains a linear speedup for every additional processor.[5][18] This network allows Folding@home to do work that was previously computationally impractical.[42]

In March 2002 Google co-founder Sergey Brin launched Google Compute as an add-on for the Google Toolbar.[97] Although limited in functionality and scope, it increased participation in Folding@home from 10,000 up to about 30,000 active CPUs.[98] The program ended in October 2005 in favor of the official Folding@home clients, and is no longer available for the Toolbar.[99] Folding@home also gained participants from Genome@home, another distributed computing project from the Pande lab and a sister project to Folding@home. The goal of Genome@home was protein design and associated applications. Following its official conclusion in March 2004, users were asked to donate computing power to Folding@home instead.[100]

Performance

On September 16, 2007, due in large part to the participation of PS3s, the Folding@home project officially attained a sustained performance level higher than one native petaFLOP, becoming the first computing system of any kind to do so.[101][102] Top500's fastest supercomputer at the time was BlueGene/L, at 0.280 petaFLOPS.[103] The following year, on May 7, 2008, the project attained a sustained performance level higher than two native petaFLOPS,[104] followed by the three and four native petaFLOPS milestones on August 20[105][106] and September 28, 2008 respectively.[107] On February 18, 2009, Folding@home achieved five native petaFLOPS,[108][109] and was the first computing project to meet these five levels.[110][111] In comparison, November 2008's fastest supercomputer was IBM's Roadrunner at 1.105 petaFLOPS.[112] On November 10, 2011, Folding@home's performance exceeded six native petaFLOPS with the equivalent of nearly eight x86 petaFLOPS.[102][113] In mid-May 2013, Folding@home attained over seven native petaFLOPs, with the equivalent of 14.87 x86 petaFLOPs. It then reached eight native petaFLOPS on June 21, followed by nine on September 9 of that year, with 17.9 x86 petaFLOPS.[114] Its current performance is given above.

Points

Similarly to other distributed computing projects, Folding@home quantitatively assesses user computing contributions to the project through a credit system.[115] All units from a given protein project have uniform base credit, which is determined by benchmarking one or more work units from that project on an official reference machine before the project is released.[115] Each user receives these base points for completing every work unit, though through the use of a passkey they can receive additional bonus points for reliably and rapidly completing units which are more computationally demanding or have a greater scientific priority.[116][117] Users may also receive credit for their work by clients on multiple machines.[39] This point system attempts to align awarded credit with the value of the scientific results.[115][115]

Users can register their contributions under a team, which combine the points of all their members. A user can start their own team, or they can join an existing team.[2] In some cases, a team may have their own community-driven sources of help or recruitment such as an Internet forum.[118] The points can foster friendly competition between individuals and teams to compute the most for the project, which can benefit the folding community and accelerate scientific research.[115][119][120] Individual and team statistics are posted on the Folding@home website.[115]

Software

Folding@home software at the user's end involves three primary components: work units, cores, and a client.

Work units

A work unit is the protein data that the client is asked to process. Work units are a fraction of the simulation between the states in a Markov state model. After the work unit has been downloaded and completely processed by a volunteer's computer, it is returned to Folding@home servers, which then award the volunteer the credit points. This cycle repeats automatically.[119] All work units have associated deadlines, and if this deadline is exceeded, the user may not get credit and the unit will be automatically reissued to another participant. As protein folding is serial in nature and many work units are generated from their predecessors, this allows the overall simulation process to proceed normally if a work unit is not returned after a reasonable period of time. Due to these deadlines, the minimum system requirement for Folding@home is a Pentium 3 450 MHz CPU with Streaming SIMD Extensions (SSE).[39] However, work units for high-performance clients have a much shorter deadline than those for the uniprocessor client, as a major part of the scientific benefit is dependent on rapidly completing simulations.[121]

Before public release, work units go through several quality assurance steps to keep problematic ones from becoming fully available. These testing stages include internal, beta, and advanced, before a final full release across Folding@home.[122] Folding@home's work units are normally processed only once, except in the rare event that errors occur during processing. If this occurs for three different users, the unit is automatically pulled from distribution.[123][124] The Folding@home support forum can be used to differentiate between issues arising from problematic hardware and bad work units.[125]

Cores

Specialized molecular dynamics programs, referred to as "FahCores" and often abbreviated "cores", perform the calculations on the work unit as a background process. A large majority of Folding@home's cores are based on GROMACS,[119] one of the fastest and most popular molecular dynamics software packages, which largely consists of manually optimized assembly code and hardware optimizations.[126][127] Although GROMACS is open-source software and there is a cooperative effort between the Pande lab and GROMACS developers, Folding@home uses a closed-source license to help ensure data validity.[128] Less active cores include ProtoMol and SHARPEN. Folding@home has used AMBER, CPMD, Desmond, and TINKER, but these have since been retired and are no longer in active service.[4][129][130] Some of these cores perform explicit solvation calculations in which the surrounding solvent (usually water) is modeled atom-by-atom; while others perform implicit solvation methods, where the solvent is treated as a mathematical continuum.[131][132] The core is separate from the client to enable the scientific methods to be updated automatically without requiring a client update. The cores periodically create calculation checkpoints so that if they are interrupted they can resume work from that point upon startup.[119]

Client

Folding@home participants install a client program on their personal computer. The user interacts with the client, which manages the other software components in the background. Through the client, the user may pause the folding process, open an event log, check the work progress, or view personal statistics.[133] The computer clients run continuously in the background at an extremely low priority, using idle processing power so that normal computer usage is unaffected.[2][39] The maximum CPU usage can be adjusted through client settings.[133][134] The client connects to a Folding@home server and retrieves a work unit and may also download the appropriate core for the client's settings, operating system, and the underlying hardware architecture. After processing, the work unit is returned to the Folding@home servers. Computer clients are tailored to uniprocessor and multi-core processors systems, as well as graphics processing units. The diversity and power of each hardware architecture provides Folding@home with the ability to efficiently complete many types of simulations in a timely manner (in a few weeks or months rather than years), which is of significant scientific value. Together, these clients allow researchers to study biomedical questions previously considered impractical to tackle computationally.[35][119][121]

Professional software developers are responsible for most of Folding@home's code, both for the client and server-side. The development team includes programmers from Nvidia, ATI, Sony, and Cauldron Development.[135] Clients can be downloaded only from the official Folding@home website or its commercial partners, and will only interact with Folding@home computer files. They will upload and download data with Stanford's Folding@home data servers (over port 8080, with 80 as an alternative), and the communication is verified using 2048-bit digital signatures.[39][136] While the client's GUI is open-source,[137] the client itself is proprietary for security and scientific integrity reasons.[138][139][140]

Folding@home uses the Cosm software libraries for networking.[119][135] Folding@home was launched on October 1, 2000, and was the first distributed computing project aimed at bio-molecular systems.[141] Its first client was a screensaver, which would run while the computer was not otherwise in use.[142][143] In 2004 the Pande lab collaborated with David Anderson to test a supplemental client on the open-source BOINC framework. This client was released to closed beta in April 2005;[144] however, the approach became unworkable and was shelved in June 2006.[145]

Graphics processing units

The specialized hardware of GPUs is designed to accelerate rendering of 3-D graphics applications such as video games and can significantly outperform CPUs for certain types of calculations. GPUs are one of the most powerful and rapidly growing computational platforms and many scientists and researchers are pursuing general purpose GPU (GPGPU) computing. However, GPU hardware is difficult to use for non-graphics tasks and usually requires significant algorithm restructuring and an advanced understanding of the underlying architecture.[146] Such customization is challenging, especially to researchers with limited software development resources. Folding@home uses the open source OpenMM library, which uses a bridge design pattern with two application programming interface (API) levels to interface molecular simulation software to an underlying hardware architecture. With the addition of hardware optimizations, OpenMM-based GPU simulations do not require significant modification but achieve performance nearly equal to hand-tuned GPU code, and greatly outperform CPU implementations.[131][147]

Before 2010 the computational reliability of GPGPU consumer-grade hardware was largely unknown, and circumstantial evidence related to the lack of built-in error detection and correction in GPU memory raised reliability concerns. In the first large-scale test of GPU scientific accuracy, a 2010 study of over 20,000 hosts on the Folding@home network detected soft errors in the memory subsystems of two-thirds of the tested GPUs. These errors strongly correlated to board architecture, though the study concluded that reliable GPU computing was very feasible as long as attention is paid to the hardware characteristics, such as software-side error detection.[148]

The first generation of Folding@home's GPU client (GPU1) was released to the public on October 2, 2006,[145] delivering a 20-30X speedup for certain calculations over its CPU-based GROMACS counterparts.[149] It was the first time GPUs had been used for either distributed computing or major molecular dynamics calculations.[150][151] GPU1 gave researchers significant knowledge and experience with the development of GPGPU software, but in response to scientific inaccuracies with DirectX, on April 10, 2008 it was succeeded by GPU2, the second generation of the client.[149][152] Following the introduction of GPU2, GPU1 was officially retired on June 6.[149] Compared to GPU1, GPU2 was more scientifically reliable and productive, ran on ATI and CUDA-enabled Nvidia GPUs, and supported more advanced algorithms, larger proteins, and real-time visualization of the protein simulation.[153][154] Following this, the third generation of Folding@home's GPU client (GPU3) was released on May 25, 2010. While backwards compatible with GPU2, GPU3 was more stable, efficient and had greater flexibility in its scientific capabilities,[155] and used OpenMM on top of an OpenCL framework.[155][156] The GPU clients do not natively support the Linux and OS-X operating systems, though Linux users with Nvidia graphics cards can run them through the Wine software application.[157][158] GPUs remain Folding@home's most powerful platform in terms of FLOPS; as of November 2012 GPU clients account for 87% of the entire project's x86 FLOPS throughput.[92]

PlayStation 3

From March 2007 until November 2012, Folding@home took advantage of the computing power of PlayStation 3s. At the time of its inception, its main streaming Cell processor delivered a 20x speed increase over PCs for certain calculations, processing power which could not be found on other systems such as the Xbox 360.[35][98] The PS3's high speed and efficiency introduced other opportunities for worthwhile optimizations according to Amdahl's law, and significantly changed the tradeoff between computational efficiency and overall accuracy, allowing for the use of more complex molecular models at little additional computational cost.[159] This allowed Folding@home to run biomedical calculations that would have been otherwise computationally infeasible.[160]

The PS3 client was developed in a collaborative effort between Sony and the Pande lab and was first released as a standalone client on March 23, 2007.[35][161] Its release made Folding@home the first distributed computing project to use PS3s.[162] On September 18 of the following year, the PS3 client became a channel of Life with PlayStation on its launch.[163][164] In terms of the types of calculations it can perform, at the time of its introduction the client took the middle ground between a CPU's flexibility and a GPU's speed.[119] However, unlike CPUs and GPUs, users were unable to perform other activities on their PS3 while running Folding@home.[160] The PS3's uniform console environment made support easier and made Folding@home more user friendly.[35] The PS3 also has the ability to stream data quickly to its GPU, which was used for real-time atomic-level visualizations of the current protein dynamics.[159]

On November 6, 2012, Sony concluded support for the Folding@home PS3 client and other services available under Life with PlayStation. Over its lifetime of five years and 7 months, more than 15 million users contributed over 100 million hours of computation to Folding@home, greatly assisting the project with disease research. Following discussions with the Pande lab, Sony decided to terminate the application. Pande considers the PlayStation 3 client a "game changer" for the project.[93][165][166]

Multi-core processing client

Folding@home can use the parallel processing capabilities of modern multi-core processors. The ability to use several CPU cores simultaneously allows completion of the overall folding simulation much faster. Working together, these CPU cores complete single work units proportionately faster than the standard uniprocessor client. This approach is scientifically valuable because it enables much longer simulation trajectories to be performed in the same amount of time, and reduces the traditional difficulties of scaling a large simulation to many separate processors.[167] A 2007 publication in the Journal of Molecular Biology relied on multi-core processing to simulate the folding of part of the villin protein approximately 10 times longer than was possible with a single-processor client, in agreement with experimental folding rates.[168]

In November 2006, first-generation symmetric multiprocessing (SMP) clients were publicly released for open beta testing, referred to as SMP1.[145] These clients used Message Passing Interface (MPI) communication protocols for parallel processing, as at that time the GROMACS cores were not designed to be used with multiple threads.[121] This was the first time a distributed computing project had used MPI.[169] Although the clients performed well in Unix-based operating systems such as Linux and Mac OS X, they were troublesome under Windows.[167][169] On January 24, 2010, SMP2, the second generation of the SMP clients and the successor to SMP1, was released as an open beta and replaced the complex MPI with a more reliable thread-based implementation.[117][135]

SMP2 supports a trial of a special category of "bigadv" work units, designed for simulating proteins that are unusually large and computationally intensive and have a great scientific priority. These units originally required a minimum of eight CPU cores,[170] which was later increased on February 7, 2012 to sixteen CPU cores.[171] In addition to these additional hardware requirements over standard SMP2 work units, they require more system resources such as RAM and Internet bandwidth. In return, users who run these are rewarded with a 20% increase over SMP2's bonus point system.[172] The bigadv category allows Folding@home to run particularly demanding simulations on long timescales that had previously required the use of supercomputing clusters and could not be performed anywhere else on Folding@home.[170]

V7

The V7 client is the seventh and latest generation of the Folding@home client software, and is a complete rewrite and unification of the previous clients for Microsoft Windows, Mac OS X and Linux operating systems.[173][174] It was released on March 22, 2012.[175] Like its predecessors, V7 can run Folding@home in the background at a very low priority, allowing other applications to use CPU resources as they need. It is designed to make the installation, start-up, and operation more user-friendly for novices, as well as offer greater scientific flexibility to researchers than previous clients.[176] V7 uses Trac for managing its bug tickets so that users can see its development process and provide feedback.[174]

V7 consists of four integrated elements. The user typically interacts with V7's open-source GUI, known as FAHControl.[137][177] This has Novice, Advanced, and Expert user interface modes, and has the ability to monitor, configure, and control many remote folding clients from a single computer. FAHControl directs FAHClient—a back-end application that in turn manages each FAHSlot (or "slot"). Each slot acts as replacement for the previously distinct Folding@home v6 uniprocessor, SMP, or GPU computer clients, as it can download, process, and upload work units independently. The FAHViewer function, modeled after the PS3's viewer, displays a real-time 3-D rendering, if available, of the protein currently being processed.[173][174]

Comparison to other molecular simulators

Rosetta@home is a distributed computing project aimed at protein structure prediction and is one of the most accurate tertiary structure predictors.[178][179] The conformational states from Rosetta's software can be used to initialize a Markov state model as starting points for Folding@home simulations.[21] Conversely, structure prediction algorithms can be improved from thermodynamic and kinetic models and the sampling aspects of protein folding simulations.[180] As Rosetta only tries to predict the final folded state, and not how proteins fold, Rosetta@home and Folding@home are complementary and address very different molecular questions.[21][181]

Anton is a special-purpose supercomputer constructed for molecular dynamics simulations. In October 2011 Anton and Folding@home were the two most powerful molecular dynamics systems.[182] Anton is unique in its ability to produce single ultra-long computationally expensive molecular trajectories,[183] such as one in 2010 which reached the millisecond range.[184][185] These long trajectories may be particularly helpful towards certain types of biochemical problems.[186][187] However, Anton does not use Markov state models for analysis. In 2011 the Pande lab constructed a MSM from two 100-µs Anton simulations and found alternative folding pathways that were not visible through Anton's traditional analysis. They concluded that there was little difference between MSMs constructed from a limited number of long trajectories or one assembled from many shorter trajectories.[183] In June 2011 Folding@home began additional sampling of an Anton simulation in an effort to better determine how its techniques compare to Anton's methods.[188][189] However, unlike Folding@home's shorter trajectories, which are more amenable to distributed computing and other parallelization techniques, longer trajectories do not require adaptive sampling to sufficiently sample the protein's phase space. Due to this, it is possible that a combination of Anton's and Folding@home's simulation methods would provide a more thorough sampling of this space.[183]

See also

- Foldit

- List of distributed computing projects

- List of software for molecular mechanics modeling

- Molecular modeling on GPUs

- SETI@home

- Storage@home

Notes

Note 1: Supercomputer FLOPS performance is assessed by running the legacy LINPACK benchmark. This short-term testing has difficulty in accurately reflecting sustained performance on real-world tasks because LINPACK more efficiently maps to supercomputer hardware. Computing systems vary in architecture and design, so direct comparison is difficult. Despite this, FLOPS remain the primary speed metric used in supercomputing.[190][191] In contrast, Folding@home determines its FLOPS using wall clock time by measuring how much time its work units take to complete.[192][193][194]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Pande lab (August 2, 2012). "About Folding@home". Folding@home. Stanford University. Archived from the original on September 21, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Pande lab (2012). "Folding@home homepage". Folding@home. Stanford University. Archived from the original on September 21, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ↑ Vijay Pande (February 18, 2013). "New FAH client, web site, and video". Folding@home. typepad.com. Retrieved February 18, 2013.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Pande lab (August 2, 2012). "Folding@home Open Source FAQ" (FAQ). Folding@home. Stanford University. Archived from the original on September 21, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 V. S. Pande, K. Beauchamp, and G. R. Bowman (2010). "Everything you wanted to know about Markov State Models but were afraid to ask". Methods 52 (1): 99–105. doi:10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.06.002. PMC 2933958. PMID 20570730.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Pande lab (July 27, 2012). "Recent Results and Research Papers from Folding@home". Folding@home. Stanford University. Archived from the original on September 21, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Vincent A. Voelz, Gregory R. Bowman, Kyle Beauchamp and Vijay S. Pande (2010). "Molecular simulation of ab initio protein folding for a millisecond folder NTL9(1–39)". Journal of the American Chemical Society 132 (5): 1526–1528. doi:10.1021/ja9090353. PMC 2835335. PMID 20070076.

- ↑ Gregory R. Bowman and Vijay S. Pande (2010). "Protein folded states are kinetic hubs". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107 (24): 10890. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10710890B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1003962107.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Christopher D. Snow, Houbi Ngyen, Vijay S. Pande, and Martin Gruebele (2002). "Absolute comparison of simulated and experimental protein-folding dynamics". Nature 420 (6911): 102–106. Bibcode:2002Natur.420..102S. doi:10.1038/nature01160. PMID 12422224.

- ↑ Fabrizio Marinelli, Fabio Pietrucci, Alessandro Laio, Stefano Piana (2009). "A Kinetic Model of Trp-Cage Folding from Multiple Biased Molecular Dynamics Simulations". In Pande, Vijay S. PLoS Computational Biology 8 (5): e1000452. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000452.

- ↑ "So Much More to Know". Science 309 (5731): 78–102. 2005. doi:10.1126/science.309.5731.78b. PMID 15994524.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Heath Ecroyd, John A. Carver (2008). "Unraveling the mysteries of protein folding and misfolding". IUBMB Life (review) 60 (12): 769–774. doi:10.1002/iub.117. PMID 18767168.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Yiwen Chen, Feng Ding, Huifen Nie, Adrian W. Serohijos, Shantanu Sharma, Kyle C. Wilcox, Shuangye Yin, Nikolay V. Dokholyan (2008). "Protein folding: Then and now". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 469 (1): 4–19. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2007.05.014. PMC 2173875. PMID 17585870.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Leila M Luheshi, Damian Crowther, Christopher Dobson (2008). "Protein misfolding and disease: from the test tube to the organism". Current Opinion in Chemical Biology 12 (1): 25–31. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.02.011. PMID 18295611.

- ↑ C. D. Snow, E. J. Sorin, Y. M. Rhee, and V. S. Pande. (2005). "How well can simulation predict protein folding kinetics and thermodynamics?". Annual Reviews of Biophysics (review) 34: 43–69. doi:10.1146/annurev.biophys.34.040204.144447. PMID 15869383.

- ↑ A. Verma, S.M. Gopal, A. Schug, J.S. Oh, K.V. Klenin, K.H. Lee, and W. Wenzel (2008). "Massively Parallel All Atom Protein Folding in a Single Day". Advances in Parallel Computing 15. pp. 527–534. ISBN 978-1-58603-796-3. ISSN 0927-5452.

- ↑ Vijay S. Pande, Ian Baker, Jarrod Chapman, Sidney P. Elmer, Siraj Khaliq, Stefan M. Larson, Young Min Rhee, Michael R. Shirts, Christopher D. Snow, Eric J. Sorin, Bojan Zagrovic (2002). "Atomistic protein folding simulations on the submillisecond timescale using worldwide distributed computing". Biopolymers 68 (1): 91–109. doi:10.1002/bip.10219. PMID 12579582.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 G. Bowman, V. Volez, and V. S. Pande (2011). "Taming the complexity of protein folding". Current Opinion in Structural Biology 21 (1): 4–11. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2010.10.006. PMC 3042729. PMID 21081274.

- ↑ Chodera, John D.; Swope, William C.; Pitera, Jed W.; Dill, Ken A. (1 January 2006). "Long‐Time Protein Folding Dynamics from Short‐Time Molecular Dynamics Simulations". Multiscale Modeling & Simulation 5 (4): 1214–1226. doi:10.1137/06065146X.

- ↑ Robert B Best (2012). "Atomistic molecular simulations of protein folding". Current Opinion in Structural Biology (review) 22 (1): 52–61. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2011.12.001. PMID 22257762.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 TJ Lane, Gregory Bowman, Robert McGibbon, Christian Schwantes, Vijay Pande, and Bruce Borden (September 10, 2012). "Folding@home Simulation FAQ". Folding@home. Stanford University. Archived from the original on September 21, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ↑ Gregory R. Bowman, Daniel L. Ensign, and Vijay S. Pande (2010). "Enhanced Modeling via Network Theory: Adaptive Sampling of Markov State Models". Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 6 (3): 787–794. doi:10.1021/ct900620b.

- ↑ Vijay Pande (June 8, 2012). "FAHcon 2012: Thinking about how far FAH has come". Folding@home. typepad.com. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved June 12, 2012.

- ↑ Kyle A. Beauchamp, Daniel L. Ensign, Rhiju Das, and Vijay S. Pande (2011). "Quantitative comparison of villin headpiece subdomain simulations and triplet–triplet energy transfer experiments". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108 (31): 12734. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10812734B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1010880108.

- ↑ Timothy H. Click, Debabani Ganguly, and Jianhan Chen (2010). "Intrinsically Disordered Proteins in a Physics-Based World". International Journal of Molecular Sciences 11 (12): 919–27. doi:10.3390/ijms11125292. PMC 3100817. PMID 21614208.

- ↑ "Greg Bowman awarded the 2010 Kuhn Paradigm Shift Award". simtk.org. SimTK: MSMBuilder. March 29, 2010. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- ↑ "MSMBuilder Source Code Repository". MSMBuilder. simtk.org. 2012. Archived from the original on October 12, 2012. Retrieved October 12, 2012.

- ↑ "Biophysical Society Names Five 2012 Award Recipients". Biophysics.org. Biophysical Society. August 17, 2011. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- ↑ "Folding@home – Awards" (FAQ). Folding@home. Stanford University. August 2011. Archived from the original on September 21, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ↑ Vittorio Bellotti and Monica Stoppini (2009). "Protein Misfolding Diseases". The Open Biology Journal 2: 228–234.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 31.4 31.5 31.6 31.7 31.8 Pande lab (May 30, 2012). "Folding@home Diseases Studied FAQ" (FAQ). Folding@home. Stanford University. Archived from the original on September 21, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Collier, Leslie; Balows, Albert; Sussman, Max (1998). Mahy, Brian; Collier, Leslie, eds. Topley and Wilson's Microbiology and Microbial Infections. 1, Virology (ninth ed.). London: Arnold. pp. 75–91. ISBN 978-0-340-66316-5.

- ↑ Fred E. Cohen & Jeffery W. Kelly (2003). "Therapeutic approaches to protein misfolding diseases". Nature (review) 426 (6968): 905–9. Bibcode:2003Natur.426..905C. doi:10.1038/nature02265. PMID 14685252.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Chun Song, Shen Lim, Joo Tong (2009). "Recent advances in computer-aided drug design". Briefings in Bioinformatics (review) 10 (5): 579–91. doi:10.1093/bib/bbp023. PMID 19433475.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 35.4 35.5 Pande lab (2012). "Folding@Home Press FAQ" (FAQ). Folding@home. Stanford University. Archived from the original on September 21, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ↑ Christian "schwancr" Schwantes (Pande lab member) (August 15, 2011). "Projects 7808 and 7809 to full fah". Folding@home. phpBB Group. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved October 16, 2011.

- ↑ Del Lucent, V. Vishal, and Vijay S. Pande (2007). "Protein folding under confinement: A role for solvent". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104 (25): 10430–10434. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10410430L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0608256104.

- ↑ Vincent A. Voelz, Vijay R. Singh, William J. Wedemeyer, Lisa J. Lapidus, and Vijay S. Pande (2010). "Unfolded-State Dynamics and Structure of Protein L Characterized by Simulation and Experiment". Journal of the American Chemical Society 132 (13): 4702–4709. doi:10.1021/ja908369h. PMC 2853762. PMID 20218718.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 39.4 Pande lab (August 18, 2011). "Folding@home Main FAQ" (FAQ). Folding@home. Stanford University. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Vijay Pande (April 23, 2008). "Folding@home and Simbios". Folding@home. typepad.com. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved November 9, 2011.

- ↑ Vijay Pande (October 25, 2011). "Re: Suggested Changes to F@h Website". Folding@home. phpBB Group. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved October 25, 2011.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Caroline Hadley (2004). "Biologists think bigger". EMBO Reports 12 (5): 236–238. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400108.

- ↑ S. Pronk, P. Larsson, I. Pouya, G.R. Bowman, I.S. Haque, K. Beauchamp, B. Hess, V.S. Pande, P.M. Kasson, E. Lindahl (2011). "Copernicus: A new paradigm for parallel adaptive molecular dynamics". 2011 International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis: 1–10, 12–18.

- ↑ Sander Pronk, Iman Pouya, Per Larsson, Peter Kasson, and Erik Lindahl (November 17, 2011). "Copernicus Download". copernicus-computing.org. Copernicus. Archived from the original on October 12, 2012. Retrieved October 2, 2012.

- ↑ G Brent Irvine, Omar M El-Agnaf, Ganesh M Shankar, and Dominic M Walsh (2008). "Protein Aggregation in the Brain: The Molecular Basis for Alzheimer's and Parkinson's Diseases" (review). Molecular Medicine 14 (7–8): 451–464. doi:10.2119/2007-00100.Irvine. PMC 2274891. PMID 18368143.

- ↑ Claudio Soto, Lisbell D. Estrada (2008). "Protein Misfolding and Neurodegeneration". Archives of Neurology (review) 65 (2): 184–189. doi:10.1001/archneurol.2007.56. PMID 18268186.

- ↑ Robin Roychaudhuri, Mingfeng Yang, Minako M. Hoshi and David B. Teplow (2008). "Amyloid β-Protein Assembly and Alzheimer Disease". Journal of Biological Chemistry (minireview) 284 (8): 4749–53. doi:10.1074/jbc.R800036200. PMID 18845536.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Nicholas W. Kelley, V. Vishal, Grant A. Krafft, and Vijay S. Pande. (2008). "Simulating oligomerization at experimental concentrations and long timescales: A Markov state model approach". Journal of Chemical Physics 129 (21): 214707. Bibcode:2008JChPh.129u4707K. doi:10.1063/1.3010881. PMC 2674793. PMID 19063575.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 P. Novick, J. Rajadas, C.W. Liu, N. W. Kelley, M. Inayathullah, and V. S. Pande (2011). "Rationally Designed Turn Promoting Mutation in the Amyloid-β Peptide Sequence Stabilizes Oligomers in Solution". In Buehler, Markus J. PLoS ONE 6 (7): e21776. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021776. PMC 3142112. PMID 21799748.

- ↑ Aabgeena Naeem and Naveed Ahmad Fazili (2011). "Defective Protein Folding and Aggregation as the Basis of Neurodegenerative Diseases: The Darker Aspect of Proteins". Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics (review) 61 (2): 237–50. doi:10.1007/s12013-011-9200-x. PMID 21573992.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 51.3 Gregory R Bowman, Xuhui Huang, and Vijay S Pande (2010). "Network models for molecular kinetics and their initial applications to human health". Cell Research (review) 20 (6): 622–630. doi:10.1038/cr.2010.57. PMID 20421891.

- ↑ Vijay Pande (December 18, 2008). "New FAH results on possible new Alzheimer's drug presented". Folding@home. typepad.com. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved September 23, 2011.

- ↑ Paul A. Novick, Dahabada H. Lopes, Kim M. Branson, Alexandra Esteras-Chopo, Isabella A. Graef, Gal Bitan, and Vijay S. Pande (2012). "Design of β-Amyloid Aggregation Inhibitors from a Predicted Structural Motif". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 55 (7): 3002–10. doi:10.1021/jm201332p. PMID 22420626.

- ↑ yslin (Pande lab member) (July 22, 2011). "New project p6871 [Classic]". Folding@home. phpBB Group. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved March 17, 2012.(registration required)

- ↑ Pande lab. "Project 6871 Description". Folding@home. Stanford University. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved September 27, 2011.

- ↑ Walker FO (2007). "Huntington's disease". Lancet 369 (9557): 218–28 [220]. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60111-1. PMID 17240289.

- ↑ Nicholas W. Kelley, Xuhui Huang, Stephen Tam, Christoph Spiess, Judith Frydman and Vijay S. Pande (2009). "The predicted structure of the headpiece of the Huntingtin protein and its implications on Huntingtin aggregation". Journal of Molecular Biology 388 (5): 919–27. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2009.01.032. PMC 2677131. PMID 19361448.

- ↑ Susan W Liebman & Stephen C Meredith (2010). "Protein folding: Sticky N17 speeds huntingtin pile-up". Nature — Chemical Biology 6 (1): 7–8. doi:10.1038/nchembio.279. PMID 20016493.

- ↑ Diwakar Shukla (Pande lab member) (February 10, 2012). "Project 8021 released to beta". Folding@home. phpBB Group. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved March 17, 2012.(registration required)

- ↑ M Hollstein, D Sidransky, B Vogelstein and CC Harris (1991). "p53 mutations in human cancers". Science 253 (5015): 49–53. Bibcode:1991Sci...253...49H. doi:10.1126/science.1905840. PMID 1905840.

- ↑ L. T. Chong, C. D. Snow, Y. M. Rhee, and V. S. Pande. (2004). "Dimerization of the p53 Oligomerization Domain: Identification of a Folding Nucleus by Molecular Dynamics Simulations". Journal of Molecular Biology 345 (4): 869–878. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2004.10.083. PMID 15588832.

- ↑ mah3, Vijay Pande (September 24, 2004). "F@H project publishes results of cancer related research". MaximumPC.com. Future US, Inc. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved September 20, 2012. To our knowledge, this is the first peer-reviewed results from a distributed computing project related to cancer.

- ↑ Lillian T. Chong, William C. Swope, Jed W. Pitera, and Vijay S. Pande (2005). "Kinetic Computational Alanine Scanning: Application to p53 Oligomerization". Journal of Molecular Biology 357 (3): 1039–1049. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2005.12.083. PMID 16457841.

- ↑ Almeida MB, do Nascimento JL, Herculano AM, and Crespo-López ME (2011). "Molecular chaperones: toward new therapeutic tools". Journal of Molecular Biology (review) 65 (4): 239–43. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2011.04.025. PMID 21737228.

- ↑ Vijay Pande (September 28, 2007). "Nanomedicine center". Folding@home. typepad.com. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved September 23, 2011.

- ↑ Vijay Pande (December 22, 2009). "Release of new Protomol (Core B4) WUs". Folding@home. typepad.com. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved September 23, 2011.

- ↑ Pande lab. "Project 180 Description". Folding@home. Stanford University. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved September 27, 2011.

- ↑ TJ Lane (Pande lab member) (June 8, 2011). "Project 7600 in Beta". Folding@home. phpBB Group. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved September 27, 2011.(registration required)

- ↑ TJ Lane (Pande lab member) (June 8, 2011). "Project 7600 Description". Folding@home. Stanford University. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved March 31, 2012.

- ↑ "Scientists boost potency, reduce side effects of IL-2 protein used to treat cancer". MedicalXpress.com. Medical Xpress. March 18, 2012. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- ↑ Aron M. Levin, Darren L. Bates, Aaron M. Ring, Carsten Krieg, Jack T. Lin, Leon Su, Ignacio Moraga, Miro E. Raeber, Gregory R. Bowman, Paul Novick, Vijay S. Pande, C. Garrison Fathman, Onur Boyman, and K. Christopher Garcia (2012). "Exploiting a natural conformational switch to engineer an interleukin-2 'superkine'". Nature 484 (7395): 529–33. Bibcode:2012Natur.484..529L. doi:10.1038/nature10975. PMC 3338870. PMID 22446627.

- ↑ Rauch F, Glorieux FH (2004). "Osteogenesis imperfecta". Lancet 363 (9418): 1377–85. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16051-0. PMID 15110498.

- ↑ Fratzl, Peter (2008). Collagen: structure and mechanics. ISBN 978-0-387-73905-2. Retrieved March 17, 2012.

- ↑ Gautieri A, Uzel S, Vesentini S, Redaelli A, Buehler MJ (2009). "Molecular and mesoscale disease mechanisms of Osteogenesis Imperfecta". Biophysical Journal 97 (3): 857–865. Bibcode:2009BpJ....97..857G. doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2009.04.059. PMC 2718154. PMID 19651044.

- ↑ Sanghyun Park, Randall J. Radmer, Teri E. Klein, and Vijay S. Pande (2005). "A New Set of Molecular Mechanics Parameters for Hydroxyproline and Its Use in Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Collagen-Like Peptides". Journal of Computational Chemistry 26 (15): 1612–1616. doi:10.1002/jcc.20301. PMID 16170799.

- ↑ Gregory Bowman (Pande lab Member). "Project 10125". Folding@home. phpBB Group. Retrieved December 2, 2011.(registration required)

- ↑ Hana Robson Marsden, Itsuro Tomatsu and Alexander Kros (2011). "Model systems for membrane fusion". Chemical Society Reviews (review) 40 (3): 1572–1585. doi:10.1039/c0cs00115e. PMID 21152599.

- ↑ Peter Kasson (2012). "Peter M. Kasson". Kasson lab. University of Virginia. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- ↑ Peter M. Kasson, Afra Zomorodian, Sanghyun Park, Nina Singhal, Leonidas J. Guibas and Vijay S. Pande (2007). "Persistent voids: a new structural metric for membrane fusion". Bioinformatics 23 (14): 1753–1759. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btm250. PMID 17488753.

- ↑ Peter M. Kasson, Daniel L. Ensign and Vijay S. Pande (2009). "Combining Molecular Dynamics with Bayesian Analysis To Predict and Evaluate Ligand-Binding Mutations in Influenza Hemagglutinin". Journal of the American Chemical Society 131 (32): 11338–11340. doi:10.1021/ja904557w. PMC 2737089. PMID 19637916.

- ↑ Peter M. Kasson, Vijay S. Pande (2009). "Combining mutual information with structural analysis to screen for functionally important residues in influenza hemagglutinin". Pacific Symposium on Biocomputing: 492–503. PMC 2811693. PMID 19209725.

- ↑ Vijay Pande (February 24, 2012). "Protein folding and viral infection". Folding@home. typepad.com. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved March 4, 2012.

- ↑ Vijay Pande (February 27, 2012). "New methods for computational drug design". Folding@home. typepad.com. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved April 1, 2012.

- ↑ Guha Jayachandran, M. R. Shirts, S. Park, and V. S. Pande (2006). "Parallelized-Over-Parts Computation of Absolute Binding Free Energy with Docking and Molecular Dynamics". Journal of Chemical Physics 125 (8): 084901. Bibcode:2006JChPh.125h4901J. doi:10.1063/1.2221680. PMID 16965051.

- ↑ Pande lab. "Project 10721 Description". Folding@home. Stanford University. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved September 27, 2011.

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 Gregory Bowman (July 23, 2012). "Searching for new drug targets". Folding@home. typepad.com. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved September 27, 2011.

- ↑ Gregory R. Bowman and Phillip L. Geissler (July 2012). "Equilibrium fluctuations of a single folded protein reveal a multitude of potential cryptic allosteric sites". PNAS 109 (29): 11681. Bibcode:2012PNAS..10911681B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1209309109.

- ↑ Paula M. Petrone, Christopher D. Snow, Del Lucent, and Vijay S. Pande (2008). "Side-chain recognition and gating in the ribosome exit tunnel". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105 (43): 16549. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10516549P. doi:10.1073/pnas.0801795105.

- ↑ Pande lab. "Project 5765 Description". Folding@home. Stanford University. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved December 2, 2011.

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 Pande lab (April 4, 2009). "Folding@home FLOP FAQ" (FAQ). Folding@home. Stanford University. Archived from the original on September 21, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ↑ Vijay Pande (March 18, 2009). "FLOPS". Folding@home. typepad.com. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ↑ 92.0 92.1 92.2 Pande lab (updated daily). "Client Statistics by OS". Folding@home. Stanford University. Archived from the original on November 28, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 Pande lab (May 30, 2012). "PS3 FAQ" (FAQ). Folding@home. Stanford University. Archived from the original on September 21, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ↑ "Most powerful distributed computing network". Guinnessworldrecords.com. Guinness World Records. September 16, 2007. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- ↑ "BOINC Combined Credit Overview". BOINCstats.com. BOINC Stats. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- ↑ Vijay Pande (November 28, 2012). "New server stats reporting page". Folding@home. typepad.com. Archived from the original on November 28, 2012. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ↑ Shankland, Stephen (March 22, 2002). "Google takes on supercomputing". CNet News. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- ↑ 98.0 98.1 "Futures in Biotech 27: Folding@home at 1.3 Petaflops" (Interview, webcast). Castroller.com. CastRoller. December 28, 2007. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- ↑ Google (2007). "Your computer's idle time is too precious to waste". Archived from the original on June 11, 2008. Retrieved August 31, 2012.

- ↑ Vijay Pande, Stefan Larson (March 4, 2002). "Genome@home Updates". April 15, 2004 Update. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- ↑ Vijay Pande (September 16, 2007). "Crossing the petaFLOPS barrier". Folding@home. typepad.com. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved August 28, 2011.

- ↑ 102.0 102.1 Michael Gross (2012). "Folding research recruits unconventional help". Current Biology 22 (2): R35–R38. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2012.01.008. PMID 22389910.

- ↑ "TOP500 List — June 2007". top500.org. Top500. June 2007. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- ↑ "Folding@Home reach 2 Petaflops". n4g.com. HAVAmedia. May 8, 2008. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- ↑ "NVIDIA Achieves Monumental Folding@Home Milestone With Cuda". nvidia.com. NVIDIA Corporation. August 26, 2008. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- ↑ "3 PetaFLOP barrier". longecity.org. Longecity. August 19, 2008. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- ↑ "Increase in 'active' PS3 folders pushes Folding@home past 4 Petaflops!". team52735.blogspot.com. Blogspot. September 29, 2008. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- ↑ Vijay Pande (February 18, 2009). "Folding@home Passes the 5 petaFLOP Mark". Folding@home. typepad.com. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved August 31, 2011.

- ↑ "Crossing the 5 petaFLOPS barrier". longecity.org. Longecity. February 18, 2009. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- ↑ Dragan Zakic (May 2009). "Community Grid Computing — Studies in Parallel and Distributed Systems". Massey University College of Sciences. Massey University. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- ↑ William Ito. "A review of recent advances in ab initio protein folding by the Folding@home project". Stanford University. Archived from the original on September 22, 2012. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ↑ "TOP500 List — November 2008". top500.org. Top500. November 2008. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- ↑ Jesse Victors (November 10, 2011). "Six Native PetaFLOPS". Folding@home. phpBB Group. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved November 11, 2011.

- ↑ Risto Kantonen (September 23, 2013). "Folding@home Stats - Google Docs". Folding@home. Google. Retrieved September 23, 2013.

- ↑ 115.0 115.1 115.2 115.3 115.4 115.5 Pande lab (August 20, 2012). "Folding@home Points FAQ" (FAQ). Folding@home. Stanford University. Archived from the original on September 21, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ↑ Pande lab (July 23, 2012). "Folding@home Passkey FAQ" (FAQ). Folding@home. Stanford University. Archived from the original on September 21, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ↑ 117.0 117.1 Peter Kasson (Pande lab member) (January 24, 2010). "upcoming release of SMP2 cores". Folding@home. phpBB Group. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ↑ "Official Extreme Overclocking Folding@home Team Forum". forums.extremeoverclocking.com. Extreme Overclocking. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- ↑ 119.0 119.1 119.2 119.3 119.4 119.5 119.6 Adam Beberg, Daniel Ensign, Guha Jayachandran, Siraj Khaliq, Vijay Pande (2009). "Folding@home: Lessons From Eight Years of Volunteer Distributed Computing". Parallel & Distributed Processing, IEEE International Symposium: 1–8. doi:10.1109/IPDPS.2009.5160922. ISBN 978-1-4244-3751-1. ISSN 1530-2075.

- ↑ Norman Chan (April 6, 2009). "Help Maximum PC's Folding Team Win the Next Chimp Challenge!". Maximumpc.com. Future US, Inc. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- ↑ 121.0 121.1 121.2 Pande lab (June 11, 2012). "Folding@home SMP FAQ" (FAQ). Folding@home. Stanford University. Archived from the original on September 21, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ↑ Vijay Pande (April 5, 2011). "More transparency in testing". Folding@home. typepad.com. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved October 14, 2011.

- ↑ Bruce Borden (August 7, 2011). "Re: Gromacs Cannot Continue Further". Folding@home. phpBB Group. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved August 7, 2011.

- ↑ PantherX (October 1, 2011). "Re: Project 6803: (Run 4, Clone 66, Gen 255)". Folding@home. phpBB Group. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved October 9, 2011.

- ↑ PantherX (October 31, 2010). "Troubleshooting Bad WUs". Folding@home. phpBB Group. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved August 7, 2011.

- ↑ Carsten Kutzner, David Van Der Spoel, Martin Fechner, Erik Lindahl, Udo W. Schmitt, Bert L. De Groot, and Helmut Grubmüller (2007). "Speeding up parallel GROMACS on high-latency networks". Journal of Computational Chemistry 28 (12): 2075–2084. doi:10.1002/jcc.20703. PMID 17405124.

- ↑ Berk Hess, Carsten Kutzner, David van der Spoel, and Erik Lindahl (2008). "GROMACS 4: Algorithms for Highly Efficient, Load-Balanced, and Scalable Molecular Simulation". Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 4 (3): 435–447. doi:10.1021/ct700301q.

- ↑ Pande lab (August 19, 2012). "Folding@home Gromacs FAQ" (FAQ). Folding@home. Stanford University. Archived from the original on September 21, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ↑ Pande lab (August 7, 2012). "Folding@home Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) Index". Folding@home. Stanford University. Archived from the original on September 21, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ↑ Vijay Pande (September 25, 2009). "Update on new FAH cores and clients". Folding@home. typepad.com. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved February 24, 2012.

- ↑ 131.0 131.1 M. S. Friedrichs, P. Eastman, V. Vaidyanathan, M. Houston, S. LeGrand, A. L. Beberg, D. L. Ensign, C. M. Bruns, V. S. Pande (2009). "Accelerating Molecular Dynamic Simulation on Graphics Processing Units". Journal of Computational Chemistry 30 (6): 864–72. doi:10.1002/jcc.21209. PMC 2724265. PMID 19191337.

- ↑ Pande lab (August 19, 2012). "Folding@home Petaflop Initiative" (FAQ). Folding@home. Stanford University. Archived from the original on September 21, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ↑ 133.0 133.1 Pande lab (February 10, 2011). "Windows Uniprocessor Client Installation Guide" (Guide). Folding@home. Stanford University. Archived from the original on September 21, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ↑ PantherX (September 2, 2010). "Re: Can Folding@home damage any part of my PC?". Folding@home. phpBB Group. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved February 25, 2012.

- ↑ 135.0 135.1 135.2 Vijay Pande (June 17, 2009). "How does FAH code development and sysadmin get done?". Folding@home. typepad.com. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved October 14, 2011.

- ↑ Pande lab (May 30, 2012). "Uninstalling Folding@home Guide" (Guide). Folding@home. Stanford University. Archived from the original on September 21, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ↑ 137.0 137.1 Folding@home developers. "FAHControl source code repository". Stanford University. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ↑ Pande lab. "Folding@home Distributed Computing Client". Folding@home. Stanford University. Archived from the original on September 21, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ↑ Vijay Pande (June 28, 2008). "Folding@home's End User License Agreement (EULA)". Folding@home. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved May 15, 2012.

- ↑ unikuser (August 7, 2011). "FoldingAtHome". Ubuntu Documentation. help.ubuntu.com. Archived from the original on September 22, 2012. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ↑ Phineus R. L. Markwick and J. Andrew McCammon (2011). "Studying functional dynamics in bio-molecules using accelerated molecular dynamics". Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 13 (45): 20053–65. Bibcode:2011PCCP...1320053M. doi:10.1039/C1CP22100K. PMID 22015376.

- ↑ M. R. Shirts and V. S. Pande. (2000). "Screen Savers of the World, Unite!". Science 290 (5498): 1903–1904. doi:10.1126/science.290.5498.1903. PMID 17742054.

- ↑ Pande lab. "Folding@Home Executive summary". Folding@home. Stanford University. Archived from the original on September 21, 2012. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ↑ Rattledagger, Vijay Pande (April 1, 2005). "Folding@home client for BOINC in beta "soon"". Boarddigger.com. Anandtech.com. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- ↑ 145.0 145.1 145.2 Pande lab (May 30, 2012). "High Performance FAQ" (FAQ). Folding@home. Stanford University. Archived from the original on September 21, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2013.