Flatiron Building

|

Flatiron Building | |

_en_2010_desde_el_Empire_State_crop_boxin.jpg) | |

Location in New York City | |

| Coordinates | 40°44′28″N 73°59′23″W / 40.74111°N 73.98972°WCoordinates: 40°44′28″N 73°59′23″W / 40.74111°N 73.98972°W |

|---|---|

| Built | 1902 |

| Architect |

D.H. Burnham & Co.: Daniel Burnham Frederick Dinkelberg[1][2] |

| Architectural style | Renaissance, Skyscraper |

| NRHP Reference # | 79001603 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | November 20, 1979[3] |

| Designated NHL | June 29, 1989 |

| Designated NYCL | September 20, 1966 |

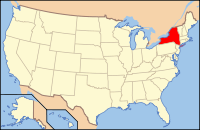

The Flatiron Building, originally the Fuller Building, is located at 175 Fifth Avenue in the borough of Manhattan, New York City, and is considered to be a groundbreaking skyscraper. Upon completion in 1902, it was one of the tallest buildings in the city and one of only two skyscrapers north of 14th Street – the other being the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company Tower, one block east. The building sits on a triangular island-block formed by Fifth Avenue, Broadway and East 22nd Street, with 23rd Street grazing the triangle's northern (uptown) peak. As with numerous other wedge-shaped buildings, the name "Flatiron" derives from its resemblance to a cast-iron clothes iron.

The building anchors the south (downtown) end of Madison Square and the north (uptown) end of the Ladies' Mile Historic District. The neighborhood around it is called the Flatiron District after its signature building, which has become an icon of New York City.[4] The building was designated a New York City landmark in 1966,[5] was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1979,[6] and designated a National Historic Landmark in 1989.[7][8]

History of the site

The site on which the Flatiron Building would stand was bought in 1857 by Amos Eno, who would shortly build the Fifth Avenue Hotel on a site diagonally across from it. Eno tore down the four-story St. Germaine Hotel on the south end of the lot, and replaced it with a seven-story apartment building, the Cumberland. On the remainder of the lot he built four three-story buildings for commercial use. This left four stories of the Cumberland's northern face exposed, which Eno rented out to advertisers, including the New York Times, who installed a sign made up of electric lights. Eno later put a canvas screen on the wall, and projected images onto it from a magic lantern on top of one of his smaller buildings, presenting advertisements and interesting pictures alternately. Both the Times and the New York Tribune began using the screen for news bulletins, and on election nights tens of thousands of people would gather in Madison Square, waiting for the latest results.[9]

During his life Eno resisted suggestions to sell "Eno's flatiron", as the site had become known, but after his death in 1899 his assets were liquidated, and the lot went up for sale. The New York State Assembly appropriated $3 million for the city to buy it, but this fell through when a newspaper reporter discovered that the plan was a graft scheme by Tammany Hall boss Richard Croker. Instead, the lot was bought at auction by William Eno, one of Amos's sons, for $690,000 – the elder Eno had bought the property for around $30,000 forty years earlier. Three weeks later, William re-sold the lot to Samuel and Mott Newhouse for $801,000. The Newhouses intended to put up a 12-story building with street-level retail shops and bachelor apartments above, but two years later they sold the lot for about $2 million to Cumberland Realty Company, an investment partnership created by Harry S. Black, CEO of the Fuller Company. The Fuller Company was the first true general contractor that dealt with all aspects of building construction except design, and they specialized in building skyscrapers.

Black intended to construct a new headquarters building on the site, despite the recent deterioration of the surrounding neighborhood,[10] and he engaged Chicago architect Daniel Burnham to design it. The building, which would be the first skyscraper north of 14th Street,[11] was to be named the Fuller Building after George A. Fuller, founder of the Fuller Company and "father of the skyscraper", who had died two years earlier, but locals persisted on calling it "The Flatiron",[2][12][13] a name which has since been made official.

Architecture

The Flatiron Building was designed by Chicago's Daniel Burnham as a vertical Renaissance palazzo with Beaux-Arts styling.[14][15] Unlike New York's early skyscrapers, which took the form of towers arising from a lower, blockier mass, such as the contemporary Singer Building (1902–1908), the Flatiron Building epitomizes the Chicago school conception:[16] like a classical Greek column, its facade – limestone at the bottom changing to glazed terra-cotta from the Atlantic Terra Cotta Company in Tottenville, Staten Island as the floors rise[17][18] – is divided into a base, shaft and capital.

Early sketches by Daniel Burnham show a design with an (unexecuted) clockface and a far more elaborate crown than in the actual building. Though Burnham maintained overall control of the design process, he was not directly connected with the details of the structure as built; credit should be shared with his designer Frederick P. Dinkelberg, a Pennsylvania-born architect in Burnham's office, who first worked for Burnham in putting together the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, for which Burnham was the chief of construction and master designer.[19] Working drawings for the Flatiron Building, however, remain to be located, though renderings were published at the time of construction in American Architect and Architectural Record.[20]

Since it employed a steel skeleton[21] – with the steel coming from the American Bridge Company in Pennsylvania[22] – it could be built to 22 stories (285 feet) relatively easily, which would have been difficult using other construction methods of that time.[23] It was a technique familiar to the Fuller Company, a contracting firm with considerable expertise in building such tall structures. At the vertex, the triangular tower is only 6.5 feet (2 m) wide; viewed from above, this pointed end of the structure describes an acute angle of about 25 degrees.

The "cowcatcher" retail space at the front of the building was not part of Burnham or Dinkelberg's design, but was added at the insistence of Harry Black in order to maximize the use of the building's lot and produce some retail income to help defray the cost of construction. Black pushed Burnham hard for plans for the addition, but Burnham resisted because of the aesthetic effect it would have on the design of the "prow" of the building, where it would interrupt the two-story high Classical columns which were echoed at the top of the building by two columns which supported the cornice. Black insisted, and Burnham was forced to accept the addition, despite the interruption of the design's symmetry.[24] Another addition to the building not in the original plan was the penthouse, which brought the building to 21 floors. It was constructed after the rest of the building had been completed to be used as artists' studios, and was quickly rented out to artists such as Louis Fancher, many of whom contributed to the pulp magazines which were produced in the offices below.[25]

New York's Flatiron Building was not the first building of its triangular ground-plan: aside from a possibly unique triangular Roman temple built on a similarly constricted site in the city of Verulamium, Britannia,[26] the Maryland Inn in Annapolis (1782), the Gooderham Building of Toronto (1892), and the English-American Building in Atlanta (1897) predate it. All, however, are smaller than their New York counterpart.

Impact

The Flatiron Building has become an icon of New York City, and the public response to it was enthusiastic, [27] but the critical response to it at the time was not completely positive, and what praise it garnered was often for the cleverness of the engineering involved. Montgomery Schuyler, editor of Architectural Record said that its "awkwardness [is] entirely undisguised, and without even an attempt to disguise them, if they have not even been aggravated by the treatment. ... The treatment of the tip is an additional and it seems wanton aggravation of the inherent awkwardness of the situation."[28] He praised the surface of the building, and the detailing of the terra-cotta work, but criticized the practicality of the large number of windows in the building: "[The tenant] can, perhaps, find wall space within for one roll top desk without overlapping the windows, with light close in front of him and close behind him and close on one side of him. But suppose he needed a bookcase? Undoubtedly he has a highly eligible place from which to view processions. But for the transaction of business?"[29]

But some saw the building differently. Futurist H. G. Wells wrote in his 1906 book The Future in America: A Search After Realities:

I found myself agape, admiring a sky-scraper the prow of the Flat-iron Building, to be particular, ploughing up through the traffic of Broadway and Fifth Avenue in the afternoon light.[30]

The Flatiron was to attract the attention of numerous artists. It was the subject of one of Edward Steichen's atmospheric photographs, taken on a wet wintry late afternoon in 1904, as well as a memorable image by Alfred Stieglitz taken the year before, to which Steichen was paying homage. (See below)[31] Stieglitz reflected on the dynamic symbolism of the building, noting that it "...appeared to be moving toward [him] like the bow of a monster ocean steamer – a picture of a new America still in the making,"[32][33] and remarked that what the Parthenon was to Athens, the Flatiron was to New York.[1] When Stieglitz' photograph was published in Camera Work, his friend Sadakichi Hartmann, a writer, painter and photographer, accompanied it with an essay on the building: "A curious creation, no doubt, but can it be called beautiful? Beauty is a very abstract idea ... Why should the time not arrive when the majority without hesitation will pronounce the 'Flat-iron'a thing of beauty?"[34]

Besides Stieglitz and Steichen, photographers such as Alvin Langdon Coburn, Jessie Tarbox Beals, painters of the Ashcan School like John Sloan, Everett Shinn and Ernest Lawson, as well as Paul Cornoyer and Childe Hassam, lithographer Joseph Pennell, illustrator John Edward Jackson as well the French Cubist Albert Gleizes all took the Flatiron as the subject of their work.[35] But decades after it was completed, others still could not come to terms with the building. In 1939, sculptor William Ordway Partridge remarked that it was "a disgrace to our city, an outrage to our sense of the artistic, and a menace to life."[36]

"23 skidoo"

When construction on the building began, locals took an immediate interest, placing bets on how far the debris would spread when the wind knocked it down. This presumed susceptibility to damage had also given it the nickname Burnham's Folly.[37] But thanks to the steel bracing designed by engineer Corydon Purdy, which enabled the building to withstand four times the amount of windforce it could be expected to ever feel,[38] there was no possibility that the wind would knock over the Flatiron Building. Nevertheless, the wind was a factor in the public attention the building received.

Due to the geography of the site, with Broadway on one side, Fifth Avenue on the other, and the open expanse of Madison Square and the park in front of it, the wind currents around the building could be treacherous. Wind from the north would split around the building, downdrafts from above and updrafts from the vaulted area under the street would combine to make the wind unpredictable.[39] This is said to have given rise to the phrase "23 skidoo", from what policemen would shout at men who tried to get glimpses of women's dresses being blown up by the winds swirling around the building due to the strong downdrafts.[40]Original tenants and subsequent history

The Fuller Company originally took the 19th floor of the building for its headquarters. In 1910, Harry Black moved the company to Francis Kimball's Trinity Building at 111 Broadway, where its parent company, U.S. Realty, had its offices. They moved them back to the Flatiron in 1916, and left permanently for the Fuller Building on 57th Street in 1929.[41]

The Flatiron's other original tenants included publishers (magazine publishing pioneer Frank Munsey, American Architect and Building News and a vanity publisher), an insurance company (the Equitable Life Assurance Society), small businesses (a patent medicine company, Western Specialty Manufacturing Company and Whitehead & Hoag, who made celluloid novelties), music publishers (overflow from "Tin Pan Alley" up on 28th Street) and other miscellaneous concerns (a landscape architect, the Imperial Russian Consulate and the Bohemian Guides Society), as well as the offices of the Roebling Construction Company, owned by the sons of Tammany Hall boss Richard Croker.

The retail space in the building's "cowcatcher" at the "prow" was leased by United Cigar Stores, and the building's vast cellar, which extended into the vaults that went more than 20 feet (6.1 m) under the surrounding streets,[42] was occupied by the Flatiron Restaurant, which could seat 1,500 patrons and was open from breakfast through late supper for those taking in a performance at one of the many theatres which lined Broadway between 14th and 23rd Streets.[43]

Even before construction on the Flatiron Building had begun, the area around Madison Square had started to deteriorate somewhat. After U.S. Realty constructed the New York Hippodrome, Madison Square Garden was no longer the venue of choice, and survived largely by staging boxing matches. The base of the Flatiron became a cruising spot for gay men, including some male prostitutes.[44] Nonetheless, in 1911 the Flatiron Restaurant was bought by Louis Bustanoby, of the well-known Café des Beaux-Arts, and converted into a trendy 400-seat French restaurant, Taverne Louis. As an innovation to attract customers away from another restaurant opened by his brothers, Bustanoby hired a black musical group, Louis Mitchell and his Southern Symphony Quintette, to play dance tunes at the Taverne and the Café. Irving Berlin heard the group at the Taverne and suggested that they should try to get work in London, which they did.[45] The Taverne's openness was also indicated by its welcoming a gay clentele, unusual for a restaurant of its type at the time.[46] The Taverne was forced to close due to the effects of Prohibition on the restaurant business.[47]

When the U.S. entered World War I, the Federal government instituted a "Wake Up America!" campaign, and the United Cigar store in the Flatiron's cowcatcher donated its space to the U.S. Navy for use as a recruiting center. Liberty Bonds were sold outside on sidewalk stands.[48] By the mid-1940s, the cigar store had been replaced with a Walgreens drug store.[49]

The building sold

In October 1925, Harry S. Black, in need of cash for his U.S. Realty Company, sold the Flatiron Building to a syndicate set up by Lewis Rosenbaum, who also owned assorted other notable buildings around the U.S. The price was $2 million, which equaled Black's cost for buying the lot and erecting the Flatiron.[50] The syndicate defaulted on its mortgage in 1933, and was taken over by the lender, Equitable Life Assurance Company after failing to sell it at auction. To attract tenants, Equitable did some modernization of the building, including replacing the original cast-iron birdcage elevators, which had cabs covered in rubber tiling and were originally built by Hecla Iron Works, but the hydraulic power system was not replaced. By the mid-1940s, the building was fully rented.[49]

Equitable sold the building in 1946 to the Flatiron Associates, an investor group headed by Harry Helmsley, whose firm, Dwight-Helmsley, which would later become Helmsley-Spear, managing the property. The new owners made some superficial changes, such as adding a dropped ceiling to the lobby, and, later, replacing the original mahogony-panelled entrances with revolving doors. Because the ownership structure was a tenancy-in-common, in which all partners have to agree on any action, as opposed to a straightforward partnership, it was difficult to get permission for necessary repairs and improvements to be done, and the building declined during the Helmsley/Flatiron Associates era. Helmsley-Spear stopped managing the building in 1997, when some of the investors sold their 52% of the building to Newmark Knight-Frank, a large real estate firm, which took over management of the property. Shortly afterwards, Helmsley's widow, Leona Helmsley, sold her share as well. Newmark made significant improvements to the property, including installing new electric elevators, replacing the antiquated hydraulic ones.[51]

The building today

As an icon of New York City, the Flatiron Building is a popular spot for tourist photographs, but it is also a functioning office building which is currently the headquarters of publishing companies held by Verlagsgruppe Georg von Holtzbrinck of Stuttgart, Germany, under the umbrella name of Macmillan, including St. Martin's Press, Tor/Forge, Picador and Henry Holt and Company.[52] Macmillan is renovating some floors, and their website comments that:

The Flatiron’s interior is known for having its strangely-shaped offices with walls that cut through at an angle on their way to the skyscraper’s famous point. These “point” offices are the most coveted and feature amazing northern views that look directly upon another famous Manhattan landmark, the Empire State Building.[52]

There are oddities about the building's interior: the bathrooms are divided, with the men's rooms on even floors and the women's rooms on odd ones; to reach the top floor, the 21st, which was added in 1905, three years after the building was completed, a second elevator has to be taken from the 20th floor; on that floor, the bottoms of the windows are chest-high.[53]

During a 2005 restoration of the Flatiron Building a 15-story vertical advertising banner covered the facade of the building. The advertisement elicited protests from many New York City residents, prompting the New York City Department of Buildings to step in and force the building's owners to remove it.[54]

In January 2009, an Italian real estate investment firm bought a majority stake in the Flatiron Building, with plans to turn it into a world-class luxury hotel, although the conversion may have to wait ten years until the leases of the current tenants run out. The Sorgente Group S.p.A., which is based in Rome, controls just over 50% of the building and plans to increase its stake. The firm's Historic and Trophy Buildings Fund owns a number of prestigious buildings in France and Italy, and was involved in buying, and then selling, a stake in New York's Chrysler Building. The value of the 22-story Flatiron Building, which is already zoned by the city to allow it to become a hotel, is estimated to be $190 million.[55]

In popular culture

In the 1958 comedy film Bell, Book and Candle, Jimmy Stewart and Kim Novak were filmed on top of the Flatiron Building in a romantic clinch, and for Warren Beatty's 1980 film Reds, the base of the building was used for a scene with Diane Keaton.[56]

Today, the Flatiron Building is frequently used on television commercials and documentaries as an easily recognizable symbol of the city, shown, for instance, in the opening credits of the Late Show with David Letterman or in scenes of New York City that are shown during scene transitions in the TV sitcoms Friends, Spin City, and Veronica's Closet. In the 1998 film Godzilla, the Flatiron Building is accidentally destroyed by the US Army while in pursuit of Godzilla, and it is depicted as the headquarters of the Daily Bugle, for which Peter Parker is a freelance photographer, in the Spider-Man movies.[57] It is shown as the location of the Channel 6 News headquarters where April O'Neil works in the show Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles TV series. The Flatiron Building is also the home of the fictional company Damage Control in the Marvel Universe comics and for the CIA sponsored, super hero management team "The Boys" in the Dynamite Comics title of the same name.[58]

In 2013, the Whitney Museum of American Art installed a life-sized 3D-cutout replica of Edward Hopper's 1942 painting Nighthawks in the Flatiron Art Space located in the "prow" of the Flatiron building. Although Hopper said his picture was inspired by a diner in Greenwich Village, the prow is reminiscent of the painting, and was selected to display the two-dimensional cutouts.[59]

Gallery

-

The building c.1903

-

Navy recruiting station in the building's "cowcatcher" during a pre-World War I "Wake up America" parade

(April 19, 1917) -

Side view

-

Rear view

-

Close-up of the apex

See also

Buildings

- List of buildings named Flatiron Building

- Herring Safe & Lock Company Building, Meatpacking District, Manhattan (1849)

- Gooderham Building, Toronto (1892)

- English-American Building, Atlanta (1897)

- Sibley Triangle Building, Rochester, New York (1897)

- Vesteda Toren, Eindhoven, the Netherlands (2006)

- Het Strijkijzer, The Hague, the Netherlands (2007)

General

References

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Morrone, Francis. "The Triangle in the Sky" Wall Street Journal (June 12, 2010)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Yardley, Jonathan. "Book review of 'Flatiron,' about a Manhattan landmark" Washington Post (June 27, 2010)

- ↑ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 2007-01-23.

- ↑ For its iconic status, see Koolhaus, Rem, Delirious New York: a retroactive manifesto (New York) 1978:72, and Goldberger, Paul, The Skyscraper (New York) 1981:38; both noted in this context in Zukowski and Saliga, 1984:79 note 3.

- ↑ New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission; Postal, Matthew A. (ed. and text); Dolkart, Andrew S. (text). (2009) Guide to New York City Landmarks (4th ed.) New York:John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-28963-1, p.76

- ↑ Pitts, Carolyn (1989-02-09). " "Flatiron Building". National Register of Historic Places Registration. National Park Service.

- ↑ "Flatiron Building". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. 2007-09-12.

- ↑ "Flatiron Building—Accompanying photos, exterior, from 1979". National Register of Historic Places Inventory. National Park Service. 1989-02-09.

- ↑ Alexiou, pp. 26-29

- ↑ Alexiou, pp. 29-41

- ↑ Alexiou, p.60

- ↑ "Flatiron Structure to be Called the Fuller Building", New York Times (9 August 1902) page 3.

- ↑ "New Building on the Flatiron" New York Times (3 March 3, 1901), page 8: "the famous 'flatiron' block"

- ↑ "Flatiron Building" on Destination 360

- ↑ Gillon, Edmund Vincent (photographs) and Reed, Henry Hope (text). Beaux-Arts Architecture in New York: A Photographic Guide New York: Dover, 1988. p.26

- ↑ The contrast is noted by Zukowsky and Saliga 1984:70ff.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 White, Norval & Willensky, Elliot (2000). AIA Guide to New York City (4th ed.). New York: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 978-0-8129-3107-5.

- ↑ Alexiou, p.74

- ↑ Other buildings by Dinkelberg at D.H. Burnham & Co. include the Santa Fe Building and the Heyworth Building, both in Chicago.

- ↑ Zukowsky and Saliga 1984:73; a perspective drawing by Jules Guérin (not a member of Burnham's office) for Century Magazine(New York Times, August 1902), now at the Art Institute of Chicago, occasioned the article in Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies.

- ↑ According to the AIA Guide to New York City (fourth edition), the belief that the Flatiron Building was one of the first building or skyscraper in New York with a steel skeleton is untrue. "[D]ozens of New York commercial buildings had been steel-framed in the 1890s, including the tallest at the time, the 391-foot Park Row Building." White, Norval & Willensky, Elliot (2000). AIA Guide to New York City (4th ed.). New York: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 978-0-8129-3107-5.

- ↑ Alexiou, p.94

- ↑ Terranova, Antonino. Skyscrapers. White Star Publishers, 2003 ISBN 88-8095-230-7

- ↑ Alexiou, pp.101-103

- ↑ Alexiou, pp.201-202

- ↑ Noted, "Roman city in Britain had Flatiron Building", The Science News-Letter 24 No. 657 (November 11, 1933:311).

- ↑ Rybczynski, Witold. City Life: Urban Expectations in a New World New York: Scribner, 1995. p.153. ISBN 0-684-81302-5. Quote: "The public loved the Flatiron, and businessmen and their architects took notice."

- ↑ Architectural Record (October 1902), quoted in Alexiou, pp.125-126

- ↑ Alexiou, p.138

- ↑ Wells, H. G. The Future in America: A Search After Realities. London:Harpers,1906.

- ↑ Alexiou, pp. 153-157

- ↑ "Skyscrapers" Magical Hystory Tour:The Origins of the Commonplace & Curious in America (September 1, 2010)

- ↑ Burns, Ric & Sanders, James New York: An Illustrated History, 233(1999)

- ↑ Alexiou, p. 156

- ↑ Alexiou, pp.158-159, 236

- ↑ In The New Yorker (August 12, 1939), quoted in Alexiou, p.126

- ↑ "Flatiron Building". Retrieved 2009-02-24.

- ↑ Alexiou, p.149

- ↑ Alexiou, pp.149-150

- ↑ Goldberger 1981:38 note 3: Andrew S. Dolkart. "The Architecture and Development of New York City: The Birth of the Skyscraper - Romantic Symbols", Columbia University, accessed May 15, 2007. "It is at a triangular site where Broadway and Fifth Avenue—the two most important streets of New York—meet at Madison Square, and because of the juxtaposition of the streets and the park across the street, there was a wind-tunnel effect here. In the early twentieth century, men would hang out on the corner here on Twenty-third Street and watch the wind blowing women's dresses up so that they could catch a little bit of ankle. This entered into popular culture and there are hundreds of postcards and illustrations of women with their dresses blowing up in front of the Flatiron Building. And it supposedly is where the slang expression "23 skidoo" comes from because the police would come and give the voyeurs the 23 skidoo to tell them to get out of the area."

- ↑ Alexiou, p.214, 244, 252

- ↑ Alexiou, p. 89

- ↑ Alexiou, pp.133-141

- ↑ Alexiou, p.223

- ↑ Mitchell would later become a headliner and nightclub owner Paris, becoming a millionaire before losing it all. He returned to the U.S., where he drove a beer truck in Washington, D.C.. Alexiou, pp.232-234, 261-264

- ↑ Alexiou, pp.220-227

- ↑ Alexiou, p.245

- ↑ Alexiou, p.232

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Alexiou, pp.264-265

- ↑ Alexiou, pp.244-245

- ↑ Alexiou, pp.264-272

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Macmillan: About

- ↑ Stapinski, Helen. "Square Feet: A Quirky Building That Has Charmed Its Tenants" New York Times (May 25, 2010)

- ↑ Lueck, Thomas J. "15-Story Ad on Flatiron Building Must Go, the City Says" New York Times (April 8, 2005)

- ↑ Sheftell, Jason "Italian real estate investor buys stake in Flatiron building, eyes hotel" New York Daily News (26 January 2009)

- ↑ Alleman, Richard. The Movie Lover's Guide to New York. New York: Harper & Row, 1988. ISBN 0060960809 pp.159-60

- ↑ Sanderson, Peter (2007). The Marvel Comics Guide to New York City. New York City: Pocket Books. pp. 36–39. ISBN 1-4165-3141-6.

- ↑ The use of the Flatiron as a visual icon for New York City increased significantly in the wake of the destruction of the World Trade Center in the 9-11 attack.

- ↑ "Famous 'Nighthawks' Painting Has Been Recreated As A 3D Installation In NYC" Huffington Post (August 16, 2013)

Bibliography

- Alexiou, Alice Sparberg. The Flatiron: the New York landmark and the incomparable city that arose with it. New York: Thomas Dunne/St. Martin's, 2010. ISBN 978-0-312-38468-5

- Zukowsky, John and Saliga, Pauline, "Late Works by Burnham and Sullivan", Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies. 11.1 (Autumn 1984:70-79)

Further reading

- Laurin, Dale. "Grace and Seriousness in the Flatiron Building and Ourselves"

- Kreitler, Peter Gwillim. Flatiron: A Photographic History of the World's First Steel Frame Skyscraper, 1901-1990. AIA Press 1991. ISBN 978-1-55835-060-1

External links

-

Media related to Flatiron Building (New York City) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Flatiron Building (New York City) at Wikimedia Commons

| ||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||