Fiscal multiplier

In economics, the fiscal multiplier (not to be confused with monetary multiplier) is the ratio of a change in national income to the change in government spending that causes it. More generally, the exogenous spending multiplier is the ratio of a change in national income to any autonomous change in spending (private investment spending, consumer spending, government spending, or spending by foreigners on the country's exports) that causes it. When this multiplier exceeds one, the enhanced effect on national income is called the multiplier effect. The mechanism that can give rise to a multiplier effect is that an initial incremental amount of spending can lead to increased consumption spending, increasing income further and hence further increasing consumption, etc., resulting in an overall increase in national income greater than the initial incremental amount of spending. In other words, an initial change in aggregate demand may cause a change in aggregate output (and hence the aggregate income that it generates) that is a multiple of the initial change.

The existence of a multiplier effect was initially proposed by Keynes student Richard Kahn in 1930 and published in 1931.[1] Some other schools of economic thought reject or downplay the importance of multiplier effects, particularly in terms of the long run. The multiplier effect has been used as an argument for the efficacy of government spending or taxation relief to stimulate aggregate demand.

In certain cases multiplier values less than one have been empirically measured (an example is sports stadiums), suggesting that certain types of government spending crowd out private investment or consumer spending that would have otherwise taken place. This crowding out can occur because the initial increase in spending may cause an increase in interest rates or in the price level.[2] In 2009, because of the use of fiscal multipliers to project the benefits of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, The Economist magazine noted "economists are in fact deeply divided about how well, or indeed whether, such stimulus works"[3] due to a lack of empirical data from non-military based stimulus. Immediately after the stimulus bill took effect, job loss slowed and private sector job growth resumed in 2010 and has continued through 2012.[4]

Net Government Spending

The other important aspect of the multiplier is that to the extent that government spending generates new consumption, it also generates "new" tax revenues. For example, when money is spent in a shop, purchases taxes such as VAT are paid on the expenditure, and the shopkeeper earns a higher income, and thus pays more income taxes. Therefore, although the government spends $1, it is likely that it receives back a significant proportion of the $1 in due course, making the net expenditure much less than $1. Indeed, in theory, it is possible, if the initial expenditure is targeted well, that the government could receive back more than the initial $1 expended.

Examples

For example: a company spends $1 million to build a factory. The money does not disappear, but rather becomes wages to builders, revenue to suppliers etc. The builders will have higher disposable income, and consumption may rise, so that aggregate demand will also rise. Suppose further that recipients of the new spending by the builder in turn spend their new income, this will raise demand and possibly consumption further, and so on.

The increase in the gross domestic product is the sum of the increases in net income of everyone affected. If the builder receives $1 million and pays out $800,000 to sub contractors, he has a net income of $200,000 and a corresponding increase in disposable income (the amount remaining after taxes).

This process proceeds down the line through subcontractors and their employees, each experiencing an increase in disposable income to the degree the new work they perform does not displace other work they are already performing. Each participant who experiences an increase in disposable income then spends some portion of it on final (consumer) goods, according to his or her marginal propensity to consume, which causes the cycle to repeat an arbitrary number of times, limited only by the spare capacity available.

Another example: when tourists visit somewhere they need to buy the plane ticket, catch a taxi from the airport to the hotel, book in at the hotel, eat at the restaurant and go to the movies or tourist destination. The taxi driver needs petrol (gasoline) for his cab, the hotel needs to hire the staff, the restaurant needs attendants and chefs, and the movies and tourist destinations need staff and cleaners.

Applications

The multiplier effect is a tool used by governments to attempt to stimulate aggregate demand. This can be done in a period of recession or economic uncertainty. The money invested by a government creates more jobs, which in turn will mean more spending and so on.

The idea is that the net increase in disposable income by all parties throughout the economy will be greater than the original investment. When that is the case, the government can increase the gross domestic product by an amount that is greater than an increase in the amount it spends relative to the amount it collects in taxes.

The difference is the fiscal stimulus. The net fiscal stimulus may be increased by raising spending above the level of tax revenues, reducing taxes below the level of government spending, or any combination of the two that results in the government taxing less than it spends.

The resulting deficit spending must be financed from government reserves (if any) or net borrowing from private or foreign investors. If the money is borrowed, it must eventually be paid back with interest, such that the long term effect on the economy depends on the trade off between the immediate increase to the GDP and the long term cost of servicing the resulting government debt.

Because businesses hire based on profits earned and available work for new employees, and not money in pocket, the goal of best utilizing the multiplier effect is to seed the money as close to the consumer base as possible, where it can be spent on industries, who will then hire new employees, who will spend their paychecks on more industries, creating a cycle. The extent of the multiplier effect is dependent upon the marginal propensity to consume and marginal propensity to import. Also that the multiplier can work in reverse as well, so an initial fall in spending can trigger further falls in aggregate output.

The concept of the economic multiplier on a macroeconomic scale can be extended to any economic region. For example, building a new factory may lead to new employment for locals, which may have knock-on economic effects for the city or region.[5]

Various types of fiscal multipliers

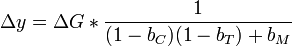

The following values are theoretical values based on simplified models, and the empirical values corresponding to the reality have been found to be lower (see below).

Note: In the following examples the multiplier is the right-hand-side equation without the first component.

- y is original output (GDP)

is marginal propensity to consume (MPC)

is marginal propensity to consume (MPC) is original income tax rate

is original income tax rate is marginal propensity to import

is marginal propensity to import is change in income (equivalent to GDP)

is change in income (equivalent to GDP) is change in lump-sum tax rate

is change in lump-sum tax rate is change in income tax rate

is change in income tax rate is change in government spending

is change in government spending is change in aggregate taxes

is change in aggregate taxes is change in investment

is change in investment is change in exports

is change in exports

Standard Income Tax Equation

[citation needed]

[citation needed]

Note: only  is here because if this is a change in income tax rate then

is here because if this is a change in income tax rate then  is implied to be 0.

is implied to be 0.

Standard Government Spending Equation

Standard Investment Equation

Standard Exports Equation

Balanced-Budget Government Spending Equation

Estimated values

United States of America

In congressional testimony given in July 2008, Mark Zandi, chief economist for Moody's Economy.com, provided estimates of the one-year multiplier effect for several fiscal policy options. The multipliers showed that any form of increased government spending would have more of a multiplier effect than any form of tax cuts. The most effective policy, a temporary increase in food stamps, had an estimated multiplier of 1.73. The lowest multiplier for a spending increase was general aid to state governments, 1.36. Among tax cuts, multipliers ranged from 1.29 for a payroll tax holiday down to 0.27 for accelerated depreciation. Making the Bush tax cuts permanent had the second-lowest multiplier, 0.29. Refundable lump-sum tax rebates, the policy used in the Economic Stimulus Act of 2008, had the second-largest multiplier for a tax cut, 1.26.[6]

According to Otto Eckstein, estimation has found "textbook" values of multipliers are overstated. The following tables has assumptions about monetary policy along the left hand side. Along the top is whether the multiplier value is for a change in government spending (ΔG) or a tax cut (-ΔT).

| Monetary Policy Assumption | ΔY/ΔG | ΔY/(-ΔT) |

|---|---|---|

| Interest Rate Constant | 1.93 | 1.19 |

| Money Supply Constant | 0.6 | 0.26 |

The above table is for the fourth quarter under which a permanent change in policy is in force.[7]

More recently three economists with the NBER and IMF have published a working paper examining economic features that impact fiscal multipliers. They found that the output effect of an increase in government consumption is larger in industrial than in developing countries, the fiscal multiplier is relatively large in economies operating under predetermined exchange rate but zero in economies operating under flexible exchange rates; fiscal multipliers in open economies are lower than in closed economies and fiscal multipliers in high-debt countries are also zero.[8]

Europe

Italian economists have estimated multiplier values ranging from 1.4 up to 2.0 when dynamic effects are accounted for. The economists used mafia influence as an instrumental variable to help estimate the effect of central funds given to local councils.[9]

IMF

In October 2012 the International Monetary Fund released their Global Prospects and Policies document in which an admission was made that their assumptions about fiscal multipliers had been inaccurate.

- "IMF staff reports, suggest that fiscal multipliers used in the forecasting process are about 0.5. our results indicate that multipliers have actually been in the 0.9 to 1.7 range since the Great Recession. This finding is consistent with research suggesting that in today’s environment of substantial economic slack, monetary policy constrained by the zero lower bound, and synchronized fiscal adjustment across numerous economies, multipliers may be well above 1.[10]

This admission has serious implications for economies such as the UK where the OBR used the IMF's assumptions in their economic forecasts about the consequences of the government's austerity policies.[11][12] It has been conservatively estimated by the TUC that the OBR's use of the IMF's under-estimated fiscal multiplication values means that they may have under-estimated the economic damage caused by the UK government's austerity policies by £76 billion.[13]

In their 2012 Forecast Evaluation Report the OBR admitted that underestimated fiscal multipliers could be responsible for their over-optimistic economic forecasts.

- "In trying to explain the unexpected weakness of GDP growth over this period, it is natural to ask whether it was caused in part by [fiscal] tightening – either because it turned out to be larger than we had originally assumed or because a given tightening did more to depress GDP than we had originally assumed.

- In answering the question, we are concerned with the aggregate impact of different types of fiscal tightening on GDP (measured using so-called ‘fiscal multipliers’) and not simply the direct contribution that government investment and consumption of goods and services makes to the expenditure measure of GDP. This direct government contribution has been more positive for growth than we expected, rather than more negative."[14]

Criticisms

Crowding out

It has been claimed that fiscal activity does not always lead to increased economic activity because deficit spending used to finance spending or tax cuts can crowd out financing for other economic activity. This phenomenon is argued to be less likely to occur in a recession, where savings rates are traditionally higher and capital is not being fully utilized in the private market.[15]

Marginal Propensity to Consume

As has been discussed, the Multiplier relies on the MPC (Marginal Propensity to Consume). The use of the term MPC here, is a reference to the MPC of a country (or similar economic unit) as a whole, and the theory and the mathematical formulae apply to this use of the term. However, individuals have an MPC, and furthermore MPC is not homogeneous across society. Even if it was, the nature of the consumption is not homogeneous. Some consumption may be seen as more benevolent (to the economy) than others. Therefore spending could be targeted where it would do most benefit, and thus generate the highest (closest to 1) MPC. This has traditionally been regarded as construction or other major projects (which also bring a direct benefit in the form of the finished product).

Clearly, some sectors of society are likely to have a much higher MPC than others. Someone with above average wealth or income or both may have a very low (short term, at least) MPC of nearly zero - saving most of any extra income. But a pensioner, for example, will have an MPC of 1 or even greater than 1. This is because a pensioner is quite likely to spend every penny of any extra income. Further, if the extra income is seen as regular extra income, and guaranteed into the future, the pensioner may actually spend MORE than the extra £1. This would occur where the extra income stream gives confidence that the individual does not need to put aside as much in the form of savings, or perhaps can even dip into existing savings.

More importantly, this consumption is much more likely to occur in local small business - local shops, pubs and other leisure activities for example. These types of businesses are themselves likely to have a high MPC, and again the nature of their consumption is likely to be in the same, or next tier of businesses, and also of a benevolent nature.

Other individuals with a high, and benevolent, MPC would include almost anyone on a low income - students, parents with young children, and the unemployed.

Externalities

It has also been argued that over-reliance upon fiscal multipliers can lead to the neglect of externalities such as environmental degradation, unsustainable resource depletion or social consequences. Negative consequences of over-reliance upon fiscal multiplication values can either be envisaged in increased government spending on activities with high fiscal multiplication values which create negative externalities (pollution, climate change, resource depletion, etc.) or through decreased spending on activities which create low immediate fiscal multiplication values but create positive externalities (educational standards, social cohesion, public health, etc.).[16]

See also

- Complex multiplier

- Fiscal policy

- Keynesian economics

- Local multiplier effect

- Multiplier (economics)

- Multiplier uncertainty

References

- ↑ Snowdon, Brian; Vane, Howard R. (2005). Modern macroeconomics: its origins, development and current state. Edward Elgar. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-84542-208-0.

- ↑ Coates, Dennis; Humphreys, Brad R. (October 27, 2004). "Caught Stealing: Debunking the Economic Case for D.C. Baseball". Cato Insititute Briefing Papers (Cato Institute) (89). Retrieved 2011-10-10.

- ↑ "Much ado about multipliers". The Economist. Sep 24, 2009. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- ↑ "A Labor Force Built to Last". Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ↑ http://www.choicesmagazine.org/2003-2/2003-2-06.htm retrieved 27 September 2007.

- ↑ Zandi, Mark. "A Second Quick Boost From Government Could Spark Recovery." Edited excerpts from congressional testimony July 24, 2008.

- ↑ Eckstein, Otto (1983). The DRI Model of the US Economy. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-018972-2. See also Bodkin, Ronald G.; Eckstein, Otto (1985). "The DRI Model of the U. S. Economy". Southern Economic Journal 51 (4): 1253–1255. doi:10.2307/1058399. JSTOR 1058399.

- ↑ Ethan Ilzetzki, Enrique G. Mendoza and Carlos A. Végh "How Big (Small?) are Fiscal Multipliers?" March 2011.

- ↑ Acconcia, A., G Corsetti and S. Simonelli, (2011) "Mafia and Public Spending: Evidence on the Fiscal Multiplier from a Quasi Experiment" CEPR Discussion Paper 8305. See http://voxeu.org/index.php?q=node/6314.

- ↑ IMF Global Prospects and Policies report 2012, page 43

- ↑ Osborne's indiscriminate austerity

- ↑ Fiscal multipliers, the IMF and the OBR

- ↑ George Osborne's austerity is costing UK an extra £76bn, says IMF

- ↑ 2012 OBR Forecast Evaluation Report, page 53

- ↑ Woodford, Michael. "Simple Analytics of the Government Expenditure Multiplier." Working Paper: Columbia University. January 27, 2010. p. 43. http://www.columbia.edu/~mw2230/G_ASSA.pdf

- ↑ What is... fiscal multiplication