Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy

| Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

16 December 1847 Paris, France |

| Died |

21 May 1923 (aged 75) United Kingdom |

| Allegiance | France, Germany |

| Service/branch | French Army |

| Years of service | 1870–1898 |

| Rank | Major |

| Commands held | French Foreign Legion |

| Battles/wars | Franco-Prussian War |

Charles Marie Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy (16 December 1847 – 21 May 1923) was a commissioned officer in the French armed forces during the second half of the 19th century who has gained notoriety as a spy for the German Empire and the actual perpetrator of the act of treason of which Captain Alfred Dreyfus was wrongfully accused and convicted in 1894 (see Dreyfus affair).

After evidence against Esterhazy was discovered and made public, he was eventually subjected to a closed military trial in 1898, only to be officially found not guilty. A revisionist theory raises the possibility that Esterhazy may have been a double agent working for the French counter-espionage service and that this could help to explain the degree of protection he received. (See section below.) This thesis has not gained general acceptance, the consensus being that the high command saw its own credibility as bound up with upholding the earlier conviction of Dreyfus.

Esterhazy retired from the military with the rank of Major in 1898—presumably under pressure—and fled by way of Brussels to the United Kingdom, where he lived in the village of Harpenden in Hertfordshire until his death in 1923.

Biography

Ancestry

Charles Marie Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy was born in Paris, France,[1] the son of General Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy who distinguished himself as division commander in the Crimean War. He inherited the prominent Hungarian family name of Esterházy through his paternal grandfather (a Nîmes merchant) who was born out of wedlock and brought up under the name of Walsin,[2] but was later acknowledged by his mother after the French Revolution of 1848. This branch of the Esterházys settled in France at the end of the 17th century and was involved in the military, namely in the organisation of Hussar regiments.

Early life and military career

Charles Ferdinand was left an orphan at an early age. After some schooling at the Lycée Bonaparte in Paris, he attempted in vain to enter the École spéciale militaire de Saint-Cyr. He disappeared in 1865. In 1869 he was found engaged in the Roman legion, in the service of Pope Pius IX.

Franco-Prussian War

In June 1870, his uncle's influence enabled him to be commissioned in the French Foreign Legion. It was an irregular commission as he had not been an enlisted soldier before.[3] However the start of the Franco-Prussian War in July prevented actions against him. He then assumed the title of count, to which he was not entitled.[4]

There being a dearth of officers after the catastrophe of Sedan, Esterhazy was able to pass muster as a French lieutenant, then as a captain, and went through the campaigns of the Loire and of the Jura. Though set back after peace was declared, he still remained in the army.

Post-war career

Between 1880 and 1882 he was employed to translate German at the French military counter-intelligence section – where he became acquainted with Major Henry and Lieutenant Colonel Sandherr, both to become major actors involved in the Dreyfus case. Then, under various pretexts, he was employed at the French War Ministry. He never appeared in his regiment at Beauvais, and for about five years led a life of dissipation in Paris, as a result of which his small fortune was soon squandered.

In 1882 he was attached to the expedition sent to Tunis, during which he did nothing to distinguish himself; employed later in the Intelligence Department, then in the native affairs of the regency. On his own authority he inserted in the official records a citation of his "exploits in war", the falseness of which was recognized later.

Returning to France in 1885, he remained in garrison at Marseille for a long time. Having come to the end of his resources, he married in 1886; but he soon spent his wife's dowry, and in 1888 she was forced to demand a separation.

In 1892, through the influence of General Saussier, Esterhazy succeeded in getting a nomination as garrison-major in the Seventy-fourth Regiment of the line at Rouen. Being thus in the neighborhood of Paris, he plunged afresh into a life of speculation and excess, which soon completed his ruin.

His inheritance squandered, Esterhazy had tried to retrieve his fortune in gambling-houses and on the stock-exchange; hard pressed by his creditors, he had recourse to the most desperate measures.

Having seconded Crémieu-Foa in his duel with Drumont in 1892, he pretended that this chivalrous role had made his family, as well as his chiefs, quarrel with him. He produced false letters to support his words, threatened to kill both himself and his children, and thus obtained, through the medium of Zadoc Kahn, chief rabbi of France, assistance from the Rothschilds (June, 1894).

This did not prevent him from being on the best of terms with the editors of the anti-Semitic newspaper La Libre Parole, even to the extent of supplying them with information.

For an officer whose original commission was illegitimate, Esterhazy's military advancement had been unusually rapid: lieutenant in 1874, captain in 1880, decorated in 1882, major in 1892. The reports on him were generally excellent.

Nevertheless, he considered himself wronged. In his letters he continually launched into recrimination and abuse against his chiefs. He went still further, bespattering with mud the whole French army, and even France herself, for which he predicted and hoped that new disasters were in store.

Dreyfus affair

Captain Alfred Dreyfus was picked by the Army as the alleged traitor in October 1894. Suspicion seems to have fallen on Dreyfus mainly because he was an outsider as both a Jew and an Alsatian. The official evidence against him depended overwhelmingly on the contention that his handwriting matched that on the bordereau. Convicted, he was formally stripped of his military rank in a public ceremony of degradation, and then shipped to the penal colony of Devil's Island (l'Île du Diable) off the coast of French Guiana.

In 1896, Lieutenant-Colonel Picquart, the then-new head of the Intelligence Service, uncovered a letter sent by Schwartzkoppen to Esterhazy. After comparison of Esterhazy's handwriting with that of the bordereau, he became convinced of Esterhazy's guilt of the crime for which Dreyfus had been convicted.

In 1897, after fruitless efforts to persuade his superiors to take the new evidence seriously and being transferred to Tunisia in an effort to silence him, Picquart provided it to Dreyfus' lawyers. They started a campaign to bring Esterhazy to justice. In 1898 an ex-lover of Esterhazy made public letters of his in which he expressed his hatred of France and his contempt for the army. However, Esterhazy was still protected by the High staff, who did not want to see the judgment of 1895 put into doubt.

In order to clear his name, Esterhazy asked for a trial behind closed doors by French Military Justice (10–11 January 1898). He was acquitted, a judgment which ignited anti-Semitic riots in Paris.

On 13 January 1898, Émile Zola published his famous J’accuse, which accused the French government of anti-Semitism and especially focused on the court-martial and jailing of Dreyfus.

Flight to Britain and later years

Esterhazy was discreetly put on military pension with the rank of Major. On 1 September 1898, having shaved off his mustache, he fled France, via Brussels, for the relative safety of the United Kingdom. From 'Milton Road' in the village of Harpenden, he continued to write in anti-Semitic papers such as La Libre Parole until his death in 1923. He is buried in St Nicholas' churchyard, Harpenden.

Revisionist thesis: Was Esterhazy a double agent?

The French historian Jean Doise espoused the revisionist hypothesis that Esterhazy might have been a French double agent masquerading as a traitor in order to pass along misinformation to the German army. Doise was not the first writer to explore the hypothesis of Esterhazy as a double agent: earlier writings by Michel de Lombarès and Henri Giscard d'Estaing, though differing in the details of their theories, also presented this line of argument.[5] According to Doise, Esterhazy's perceived bitterness and utter lack of patriotic feeling, along with his fluency in German, were qualities which would have helped him to pose as an effective and unrepentant traitor.[6]

In Tunis he was judged to have become too intimate with the German military attaché. In 1892 he was the object of an accusation made to the head of the staff, General Brault. In 1893 he entered (or, if one accepts the revisionist explanation, pretended to enter) the service of Max von Schwartzkoppen, the German military attaché in Paris.

According to later disclosures he received from the German attaché a monthly pension of 2,000 marks ($480). In return, Esterhazy furnished him in the first place with information (or, it is argued, misinformation) about artillery.

Esterhazy reported that he got his information from Major Henry, who had been his comrade in the French military counter-intelligence section of the War Ministry, in 1876. However, Henry, limited to a very special branch of the service, was hardly in a position to furnish details on technical questions. The main architect of the disinformation campaign is claimed to have been Colonel Sandherr, head of French military counter-intelligence.[6]

The lack of value of the material furnished by Esterhazy soon became so apparent that Panizzardi, the Italian military attaché, to whom Schwartzkoppen communicated it without divulging the name of his informant, began to doubt his qualifications as an officer. To convince the attaché it was necessary for Esterhazy to show himself one day in uniform, galloping behind a well-known general.

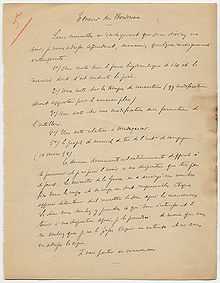

The infamous document, or "bordereau", used to convict Dreyfus had been retrieved in a waste paper basket at the German Embassy by a cleaning lady who was in the employ of French military counter-intelligence. This document had been torn up but was easily pieced together. It announced, among other items, a forthcoming report on a new French 120mm howitzer [Canon de 120C Modele 1890 Baquet] and the comportment of its hydraulic recoil mechanism, as well as detailed manuals describing the current organization of French field artillery."[6]

In fact, however, the French army had already rejected the 120 mm model as unworkable and had begun development of the revolutionary (for its time) 75 mm field gun. The argument is thus made that the document was designed to prevent the Germans from discovering the development of the French 75.[6]

The novel "A Man in Uniform: A Novel" by the Canadian author Kate Taylor, first published in Canada in 2010, a fictional detective story set in Paris at the end of the 19th century against the background of the Dreyfus affair, contains a reference to Esterhazy as the "unwitting double agent" of a character named Masson.[7]

However, there are reports of Esterhazy admitting that he had "indeed been a spy for Germany".[8] As such, the historical revisionism theories proposing that Esterhazy was merely pretending to be a spy are controversial (and considered untrue) as they deny concrete evidence of Esterhazy spying against France.

Consequently, Esterhazy was the real author of the memorandum used to falsely convict Alfred Dreyfus considering that he confessed in a newspaper article that he composed the memorandum which instigated the Dreyfus affair.[9]

References

- ↑ Singer, Isidore (1912). The Jewish Encyclopedia, Volume 4. New York, London: Funk and Wagnalls. p. 671. ISBN 978-1-23-218889-6.

- ↑ http://gw1.geneanet.org/elsa2002?lang=fr&p=jean+marie+auguste&n=walsin+esterhazy

- ↑ Serman, W. (1979). Les Origines des officiers français. 1848–1870. Paris: Publications de la Sorbonne. ISBN 2-85944-015-1.

- ↑ As descendant of a bastard of a daughter of Esterhazy, he was not entitled to a title which does not pass (1) to bastards (2) to daughters.

- ↑ Bredin, Jean-Denis (1986). The Affair: The Case of Alfred Dreyfus. New York: George Braziller. pp. 512–515. ISBN 0-8076-1109-3.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 France at War – The Dreyfus Case and the French 75

- ↑ Taylor, Kate (2011-01-18). A Man in Uniform: A Novel. ISBN 9780307885210.

- ↑ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/193419/Ferdinand- Walsin-Esterhazy

- ↑ http://www.dreyfus.culture.fr/en/bio/bio-html-ferdinand-walsin-esterhazy.htm

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press

External links

|